Ask not what contemporary art is, but what contemporary art should be.

—Oksana Pasaiko, 2009

I.

“What is contemporary art?” is (clearly) not the same question as “What is art?” The former basically asks us to define what is particularly “contemporary” about art—not, significantly enough, what is particularly artistic about it. The question of what is “contemporary” about contemporary art seems straightforward enough: answering it would simply require our invoking all the art that is being made now—but of course there is more.

Now, answering the question as to what is particularly artistic about art (contemporary or not) is famously impossible, and it belongs to the specific condition of contemporary art (or at least of the contemporary art world, which may or may not be the same1) to have made the very act of asking this question not just impossible, but also unreasonable, even irresponsible—a show of poor taste or, worse still, of irreversible disconnect from the daily practice of (contemporary) art. Contributing to, or participating in, something that does not tolerate definition or other forms of circumscription (so being part of something that is ultimately unknowable: not knowing what we’re doing) is one of the ways in which “culture” in general essentially reproduces itself. This is an important nuance to distinguish, for it necessarily means that contemporary art belongs to the general field of “culture,” whereas art does not (that is to say, not necessarily). And this, in turn, is not necessarily a good thing; in fact, it may be a bad thing. It probably is a bad thing. Alain Badiou, in his introduction to Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism, remarks that

the contemporary world is doubly hostile to truth procedures. This hostility betrays itself through nominal occlusions: where the name of a truth procedure should obtain, another, which represses it, holds sway. The name “culture” comes to obliterate that of “art.” The word “technology” obliterates the word “science.” The word “management” obliterates the word “politics.” The word “sexuality” obliterates love. The “culture-technology-management-sexuality” system, which has the immense merit of being homogenous to the market, and all of whose terms designate a category of commercial presentation, constitutes the modern nominal occlusion of the “art-science-politics-love” system, which identifies truth procedures typologically.2

It is no coincidence that this poignant lament should start with the fate of art (and not, more predictably, with an assessment of the debased status of the political in the contemporary society our fiery Frenchman so tersely describes): Badiou’s thought is inscribed in the long history of a philosophical valuation of art above all other realms of human activity (even as the singularly humanizing force in all of this activity)—a complex history, riddled with contradictions of all sorts, which long ago acquired its canonical form in the heroic figuration of German Idealism.

II.

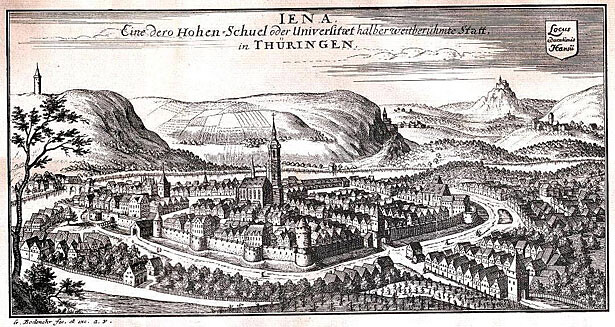

There are three moments, events, conjectures in the history of philosophy—which is always also/already a history of art (in that it is always also/already a history of the philosophy of art)—that would undoubtedly make for great, unforgettable movie scenes, maybe even for great, unforgettable movies. In fact, the inevitability of their greatness is probably the one reason why I would want to entertain the fantasy of venturing into the world of movie-making proper, with or without the help of an artist friend. The first of these scenes would be set in Athens around the time of Socrates’ trial; the second one in Jena during the early years of the nineteenth century; the third in Pacific Palisades and neighboring Brentwood during the Second World War. The first scene would feature Socrates himself, of course, along with his heir apparent, Plato, and a motley crew of Atomists, Eleatics, Pythagoreans, Sophists, and the like; in the second scene, such notables as Fichte, Hegel, Novalis, Schelling, Schiller, and (only passing through!) Schleiermacher would appear; in the last scene, Charlie Chaplin would be playing tennis with Sergei Eisenstein while Theodor Adorno and Arnold Schoenberg would be caught bickering over the former’s preparatory notes for Doktor Faustus at a barbecue hosted by the author of this dodecaphonic novel, Thomas Mann. If a fourth scene were to be called for, it would probably show Plato, Hegel, and Adorno crossing paths on Manhattan’s Lower East Side—or in a studio in the Soho of the seventies, perhaps Lawrence Weiner’s. (Indeed, it is very tempting to imagine the Soho of the seventies as the last great art-historical equivalent of 1800s Jena).

So we have called these three high-water marks in the history of philosophy “moments” in the history of art. And surely the scene set in Jena AD 1806 captures the history of philosophy as a history of the philosophy of art (and hence also of art proper) at its undisputed acme—a triumphant scaling of the heights after which nothing but the long descent to the banal plains of the “now” could follow. If German Idealism is indeed often referred to as the World Spirit’s finest hour, this is in no small measure because of the centrality accorded to the question of art at the very zenith of philosophy’s historical development: German Idealism needed art to become what it became—or rather, it needed its conceptualization (again, much like Concept Art itself in our beloved, bedeviled twentieth century).

This relationship of inner (“philosophical”) necessity and profound dependence is not necessarily one of great love or even sympathy—its roots reach far deeper. Indeed, if one thing is especially noteworthy in this respect, it is the fact that neither the father of German Idealism, Immanuel Kant, nor his talented, rebellious philosophical offspring (Hegel first and foremost, but the now more easily forgotten Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling certainly occupied a position of similar prominence), were terribly interested in the practical reality of art, let alone very artistically minded themselves. Present-day readers of Kant’s Critique of Judgment or Hegel’s Aesthetics will fruitlessly look for passing references to actual artworks produced in their lifetime (certainly of the visual kind), and it is truly frustrating to realize that they were the contemporaries of such iconic image-makers as J. M. W. Turner, Caspar David Friedrich, and Jacques-Louis David, about whose work they remained forbiddingly silent. On the contrary, they were primarily interested in aesthetics—but still needed the extremely powerful idea of “real” art to lend this primary interest a salient quality, thus shaping a blueprint of sorts for all future engagements of established philosophical practice with artistic practice. [It is far too facile to say that philosophers do not “understand” art, or habitually only “discover” certain artists, art forms, art practices, and/or artworks long after their prime or the moment of their historical emergence/emergency; philosophy’s relationship with art is much more complicated than this—while art’s relationship with philosophy is probably much less complicated.3]

Here follows an extensive quote from Andrzej Warminski’s illuminating introduction to Paul de Man’s Aesthetic Ideology—and we really could not have put it any better:

For both Kant and Hegel, the investment in the aesthetic as a category capable of withstanding “critique” (in the full Kantian sense) is considerable, for the possibility of their respective systems’ being able to close themselves off (i.e., as systems) depends on it: in Kant, as a principle of articulation between theoretical and practical reason; in Hegel, as the moment of transition between objective spirit and absolute spirit… For without an account of reflexive aesthetic judgment in Kant’s third Critique, not only does the very possibility of the critical philosophy itself get put into question but also the possibility of a bridge between the concepts of freedom and the concepts of nature and necessity, or, as Kant puts it, the possibility of “the transition from our way of thinking in terms of principles of nature to our way of thinking in terms of principles of freedom.” … The project of Kant’s third Critique and its transcendental grounding of aesthetic judgment has to succeed if there is to be—as “there must after all be,” says Kant, “it must be possible”—“a basis uniting [Grund der Einheit] the supersensible that underlies nature and that the concept of freedom contains practically”; in other words, if morality is not to turn into a ghost. And Hegel’s absolute spirit (Geist) and its drive beyond representation (Vorstellung) on its long journey back home from the moment of “objective spirit”—that is, the realm of politics and law—to dwell in the prose of philosophical thought’s thinking itself absolutely would also turn into a mere ghost if it were not for its having passed through the moment of the aesthetic, its phenomenal appearance in art, “the sensory appearance of the Idea.” In other words, it is not a great love of art and beauty that prompts Kant and Hegel to include a consideration of the aesthetic in their systems but rather philosophically self-interested reasons. As de Man put it in one of his last seminars, with disarming directness and brutal good humor: “therefore the investment in the aesthetic is considerable—the whole ability of the philosophical discourse to develop as such depends entirely on its ability to develop an adequate aesthetics. This is why both Kant and Hegel, who had little interest in the arts, had to put it in, to make possible the link between real events and philosophical discourse.”4

I have long liked the fatalist sound of this “had-to-put-it-in” in particular: it speaks to a basic reluctance on the part of philosophy to accept that only one thing is more important (“higher”) than philosophy, namely, art—the grudging acknowledgement (and this grudge may well be the source of all critique) that art, as a very precisely delineated philosophical concept that is absolutely distinct from the general notion of culture, is simply the most important thing, namely, that on which all other thinking (including that of “culture”) hinges.

III.

Although we have, of course, long since given up any attempts at truly defining this thing called “art” (and already in German Idealism it is clear that not so much art as its concept is the object of reverence and scrutiny, and that it will henceforth be approached purely negatively5), today we continue to live and work, to labor and love, under the aegis of this one tenacious assumption—that art simply is the most important thing, and that if a thing is named art, it is thereby made the most important thing, possibly even the only thing. And perhaps this is all the definition we need.

“Art” is not just (it is in fact far from) a madding crowd of images, objects, and pictures of objects, nor does its name simply refer to the mass of people who produce the aforementioned; art is not just that which is shown or talked or written about in the various spaces of art, however fleeting or fixed, “solid” or “melting”; and it certainly is not just the subject of art history, art criticism, and/or art curating. Finally, “art” is not just an archipelago of institutions, physical or otherwise, scattered around the world in time as well as space, accruing to a parallel universe that appears more or less disconnected from a supposedly “realer” world down below (or up above, if you still believe in the underground).

It is all of these things put together, for sure, and then some: art is the word, or, better still, the name of a great theme, of mankind’s greatest idea, its single lasting sentence—the name of a hope and of something that has yet to come: the unfulfilled and/or that which eternally lies ahead. Not a thing of the past, then. This, precisely, is where the view from Jena sharpens its focus: like history, science, and society, art is one of the great concepts of “modern” culture—and because we already know what our indifference and careless disregard (posing as “critique”) has done to those other concepts, we must forever, and now more than ever, especially in the face of its dissolution in the monochromatic miasma of a “culture” that is no longer so modern, rally to its defense.6 We must, in a certain sense, stand up against the gradual encroachment of this generalized culture upon the domain of art—that process of willful confusion that is so characteristic of that which is specifically “contemporary” in contemporary art, namely its very state of confusion (as to its own future, borders, and sense of “belonging”).

Imagine that someone would one day say: “there is no such thing as art” (someone else, and someone very powerful too, once said that “there is no such thing as society,” and we know now what that has lead to)—now that would be very disturbing indeed. Then what? What would we do, what would we talk about, and where would we go? Whom would we know and how (on earth) would we ever get to meet them? Let us briefly conjure the image of a truly art-less world, and imagine the panic this would spark, probably very much like the panic a similar prospect or thought would have sparked among the well-read inhabitants of Jena in AD 1806: wouldn’t this be much like the end of the world?

IV.

Let us return to the alarmist, apocalyptic tenor of Alain Badiou’s indictment of the “culture-technology-management-sexuality” system as that which has come to occlude the “art-science-politics-love” system. We have already noted how this process of occlusion really goes hand-in-hand with a process of confusion—of art’s own confusion, that is, concerning its relationship to a cultural system (one that used to be called “mass culture” or “popular culture,” but those terms have certainly lost their legitimacy) that it clearly desires to be immersed in, or just belong to; a confused desire for its own disappearance into something other, bigger, badder. Now, in thus constructing a one-dimensionally affirmative relationship (namely one of mimetic desire) with an essentially affirmative cultural complex, contemporary art has become a hugely influential affirmative force in itself—and once again, its insistence on being “contemporary” is precisely what helps to define and determine its affirmative character: not only is it merely “of” the times (the minimal definition of contemporaneity), it basically bestows value upon these times simply by so desperately wanting to infiltrate, inhabit, and if possible even shape it. This great yea-saying ritual is best expressed in contemporary art’s reluctance, if not outright refusal—and that is as close as it comes to assuming a programmatic stance—to preclude certain (that is to say, any) forms, practices, or tropes from being named art. We have long known that anything and everything can be art, but in our contemporary cultural climate this equation has taken on a different quality, one in which, conversely, contemporary art can be anything and everything. [Or that everything is permitted, to paraphrase Ivan Karamazov.] The critical question then becomes not so much “what is contemporary art?” but, much more typical for contemporary art as such: “what is not contemporary art?”

V.

If art does not (or should not) “belong” to culture, or rather belongs to a different, probably older order of being (or becoming), and if “culture” is the name of the web of desirous artifice that has come to engulf and wholly cover today’s global village (how quaint that phrase already sounds!), then it is probably not too far-fetched to call art, that absent (“occluded”) thing such as Badiou and I conceive of it, “a thing of the past”—and here, of course, the Hegelian circle magically closes itself, for that is precisely why Hegel-the-art-theorist is probably best remembered today: for calling art (“on the side of its highest destiny”7) a thing of the past long before art, as we came to know it, came into its own. The view from Jena was already a melancholy backward glance, “theory” or philosophy its only remaining source of solace (and in this sense I certainly continue to reside in Jena anno 1806).

But didn’t we just call art “the name of a hope and of something that has yet to come: the unfulfilled and/or that which eternally lies ahead”? Indeed we did. Now if art is both (and simultaneously) a thing of the past and a thing of the future, this merely means that there is no art “now”—and that, indeed, is precisely what contemporary art foolishly claims: it wants to be culture instead.8

This may all sound very grim perhaps—but it really isn’t. We just patiently wait for the clouds to clear and the confusion to cease; it won’t be long.

But I am afraid it is the same.

Alain Badiou, Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 12. Badiou’s identification of art, science, politics, and love as the four fields of human activity that yield truth is a central claim of his philosophical project.

There are many reasons for the German Idealists’ depreciation of the artistic achievements of their own time, but one reason “why Schelling and Hegel, among others, underrated German art” is particularly noteworthy in the current context: it concerned “their belief that in times of intense artistic creativity … there is little reflection on art. Thought about art, and philosophy of art, arise only when art is in decline… And Hegel’s age was above all an age of criticism and of reflective thought about art.” Michael Inwood, introduction to Hegel’s Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics, trans. Bernard Bosanquet (London: Penguin Books, 1993), xi. Perhaps this remark could help to solve the riddle asked by Frieze Magazine on the cover of their September 2009 issue, “Whatever happened to theory?”

Andrzej Warminski, “Introduction: Allegories of Reference,” in Paul de Man, Aesthetic Ideology (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 3–4. The Kant quotation is taken from his Critique of Judgment, trans. Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987). The concluding quotation by de Man is taken from notes compiled under the title “Aesthetic Theory from Kant to Hegel,” delivered in the fall of 1982 at de Man’s alma mater, Yale.

A classic example of the persistence of this via negativa in our time is presented by Giorgio Agamben in his essay “Les jugements sur la poésie…”: “Caught up in laboriously constructing this nothingness”—i.e., the “negative theology” (this is the term Agamben actually uses) of criticism—“we do not notice that in the meantime art has become a planet of which we only see the dark side, and that aesthetic judgment is then nothing other than the logos, the reunion of art and its shadow. If we wanted to express this characteristic with a formula, we could write that critical judgment, everywhere and consistently, envelops art in its shadow and thinks art as non-art. It is this “art,” that is, a pure shadow, that reigns as a supreme value over the horizon of terra aesthetica, and it is likely that we will not be able to get beyond this horizon until we have inquired about the foundation of aesthetic judgment.” See The Man Without Content, trans. Georgia Albert (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 43–44. A more elegant proposal, no less negatively worded, however, is formulated by Thierry De Duve in the justly celebrated opening pages of his landmark tome Kant After Duchamp, where he invites the reader to imagine herself an anthropologist hailing from outer space trying to figure out what humans mean when they name something, anything “art”: “You conclude that the name ‘art,’ whose immanent meaning still escapes you—indeterminate because overdetermined—perhaps has no other generality than to signify that meaning is possible.” See Kant After Duchamp (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996), 5–6.

I am of course perfectly aware of the apparent arbitrariness with which different notions of culture are bandied around and played out against each other here; as is the case with “art,” the impossibility of really defining “culture” is partly determined by the culture to which such questions of definition necessarily belong. The question of contemporary culture as that which presently engulfs art and from which, I believe, “art” should be saved, is a central concern of Terry Eagleton’s After Theory (both Eagleton and his mentor Raymond Williams are, of course, key authors in the art-and-culture debate): “pleasure, desire, art, language, the media, body, gender, ethnicity: a single word to sum all these up would be culture.” After Theory (London: Basic Books, 2004), 39.

The reference here is to the following celebrated, oft-quoted (and just as often misread) passage: “In all these respects art is, and remains for us, on the side of its highest destiny, a thing of the past.” Hegel, Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics, 13. This statement has often been misread as a proclamation of the end of art; Hegel himself provides the qualifying commentary, stating that “this claim excludes the possibility of great and/or intellectually authoritative art in the present and the foreseeable future, but not in the distant future. But such an art of the future would not be ‘for us.’” Ibid., 105. (It would be “for us,” though). The amount of commentary this seemingly casual remark has spawned continues to baffle and astound; Arthur C. Danto and Donald Kuspit are some of this exegetic tradition’s most prominent representatives.

There is no more powerful symbol of this state of diffusion, which Agamben (see note 5) would describe as “art now,” than the series of books published under the best-selling title “Art Now” by Taschen Verlag.

Category

The author would like to thank Will Holder and FR David for allowing some of these thoughts, first formulated for the latter, to appear online. I would also like to acknowledge Jørgen Lund from the University of Bergen for sharing some of his beautifully formulated ideas on art (paraphrased in chapter III) with me at a conference organized at the Bergen Kunsthall in August 2009.