1.

I once had an accidental encounter with Mount Gyeryong and an indescribable shock came over me. The light of the full moon allowed the mountain, covered in snow, to reveal itself in its full glory even in the middle of the night. Unlike other large mountains in South Korea, which one can rarely see fully because they are usually hidden by neighboring peaks, Mount Gyeryong is a so-called protrusion-in-the-field type of mountain whose overall shape is quite visible even from a distance.

I suspect that the experience I had was akin to what is called “the sublime” in Western aesthetics. The theory of the sublime, only introduced to South Korea with theories of postmodernism, seems to have been revived here in the wake of September 11, 2001. Prior to that, in Western society, looking at the culture of the relatively recent past, we can also identify recurrent revivals of the aesthetics of the sublime in diverse genres, as for example Werner Herzog’s film Nosferatu, which borrows from Caspar David Friedrich’s landscapes; all the disaster films that simulate Turner’s stormy seas and other Romantic painters’ images of ruins; and the montage of primitive sacrificial rites in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. By now the aesthetics of the sublime, more than its theory, has become a familiar part of South Korean visual culture. And this is, in a sense, only natural, for if the concept of the sublime is premised on given conditions such as death, nature, and the infinite nature of the universe, then the concept is not specific to the West but universal for all humanity. If the sublime can be explained as a Kantian universal human experience (even though the German philosopher distinguished between peoples who are close to the sublime and those who are far from it), then we can also attempt to explain how it functions in Korea and Northeast Asia. So my question—to which I have no clear answer—is: How has the sublime manifested itself in Korean and Northeast Asian cultures? If certain traditions can correspond to the sublime, in what ways might we now make works of art, and what meanings and values would such representations have?

2.

In Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s well-known film Tropical Malady (2004), the protagonist passes through bizarre locations on his way into a deep jungle, where he suddenly enters the time-space of a fable in which he can converse with animals. Ultimately, lost in the jungle in the middle of night, he comes face to face with a tiger, or the ghost of a tiger. On the one hand, I suspect that Tropical Malady might be yet another example of contemporary Orientalism. On the other hand, I have a strong sense of solidarity with such a sensibility. And this sensibility, perhaps, parallels my childhood memory of accompanying my parents to the mass of the forty-ninth day for a dead distant relative by marriage, where I saw golden Buddha statues and paintings of Buddhist deities and mountain spirits through candlelight and incense smoke in a temple deep in the mountains.1 I am also thinking about the old Asian paintings of bizarre-looking rocks I have seen in museums. Such experiences inspire in me—as they do in probably all of us—one of the most important human emotions, that of fear/awe.

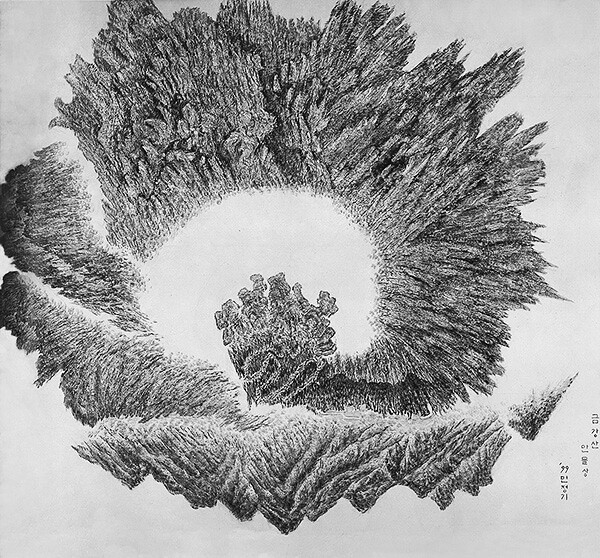

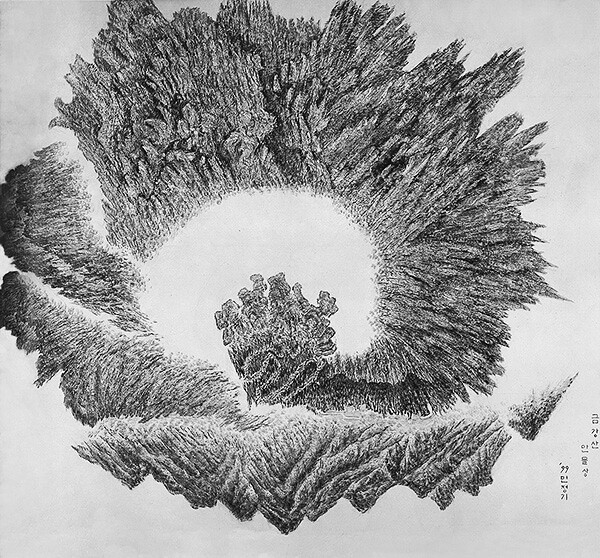

Fear/awe is without a doubt informed by local nature and culture, because it has long been inherent in the experience of them. In this sense, Mount Gyeryong is not a Korean version of the Alps but rather relates to its own “site-specific” aesthetics. One may question, of course, whether my generation’s urban culture has already been severed from such aesthetics, and furthermore, whether I may be forcing a theory. The opposite point, however, could just as easily be made. The hermitages and old temples one happens upon deep in the mountains, precisely because of their remoteness, can appear even more unexpected, difficult to interpret, and jolting. From the publication of Yoo Hong-jun’s book My Survey of Cultural Heritages, which inspired a traditional-culture tourism boom during the 1990s in South Korea, to the current situation in which the world has become an enormous photographic archive thanks to technologies like Google Earth, the old, the deep, and the fearful have increasingly fewer places to hide.2 When poet Kim Ji-ha speaks endlessly and almost with a certain naïveté about the importance of Haewol Philosophy, and when Choi In-hoon feels a profound remorse when faced with the ruins of Goryeo Dynasty–era Buddhist temples, are such emotions really so remote?3 Furthermore, when the dreams of Buddhistic salvation found in the work of writer Kim Seong-dong and the Korean Romanticism of film director Im Kwon-taek’s fixation on traditional culture are taken to have a certain remoteness from their subject, do they not appeal to us even more poignantly?4 Or, to use examples from art, what about Park Saeng-gwang’s talisman-like pictures of shamans, Oh Yoon’s humorous images of demons, and Min Jeong-gi’s bizarre paintings of Mount Geumgang?5

Min Joung Ki, Manmulsang at Guemgang Mountain, 1999, oil on canvas, 333 x 224 cm

For members of the generation to which such cultural figures belong, connecting traditional culture and Korean nature seems to have been a critical problem or a grand exercise, and these figures could gamble their whole lives on rescuing (modernizing?) their respective virtues. Even if many among this generation either retreated into mysticism or ended up devoting themselves to a “cultural nationalism,” their efforts continue to be valuable as a series of relentless demands for the correction of the excessive, violent imbalance between Western culture and Korean culture. (Of course, we still need to guard against absurdly conservative tastes, exemplified by the Department of Oriental Painting in Seoul National University’s College of Fine Arts or the right-wing nationalism of Lee Moon-yeol.)6 If the experience of this generation was defined primarily by a separation between city and countryside and by the various speeds of development, for my generation—especially someone like me who was born in Seoul and raised as a Catholic in a high-rise apartment complex—Korean traditional culture, especially traditional religious culture, is unfamiliar from the very start and may even be said to belong more to the realm of the imagination than to reality.

This is why I always postpone doing anything about tradition, like a patient not wanting to go to the hospital or a student not wanting to do homework. However, the more you postpone something, the more burdensome it becomes. Ultimately, like a rock that you repeatedly trip over because you have neglected to move it out of the way, it becomes something you end up regretting somewhere down the line. Might this recurrent postponement and return of tradition become an obsession, or could it be a type of wisdom that has yet to be defined clearly? At least one thing is clear. Whether it is an obsession or an anticipation of a certain wisdom, tradition is something that touches on “the unconscious,” a force that grabs the back of your head, a fascination that disturbs “my” modernization, and, to use recent parlance, a typical Other. The anxiety I feel from being estranged from tradition seems always to take up half of my capacity for thinking and cultural reception. Therefore, what is more interesting to me than the reconstitution or modernization of tradition is the notion that tradition—as a kind of Other, and in the sense that it appears like an unknowable specter—is a sort of “local wound,” which has only symptoms but no identifiable scientific diagnosis. If modernity was a traumatic experience in the recent past, then tradition is this resulting wound.

3.

Elements of traditional Korean culture have survived into everyday contemporary life in many ways, such as the persistence of ondol (subfloor heating systems). Of these, religious cultures have the longest and most tenacious life. On the one hand, it goes without saying that traditional society maintained a firmer and far more quotidian relationship with religion and mythology. On the other hand, the religious culture and mythological structure of traditional society were what contrasted most sharply with, and were thus most deeply hidden during, the process of modernization. More than anything else, traditional religious culture represents a significant trauma. For instance, it was Donghak (Eastern Learning) that fought most fiercely against Japanese imperialism and was most tragically defeated by it.7 Donghak exemplifies the greatest historical wound inflicted throughout the course of the modernization of Korea.

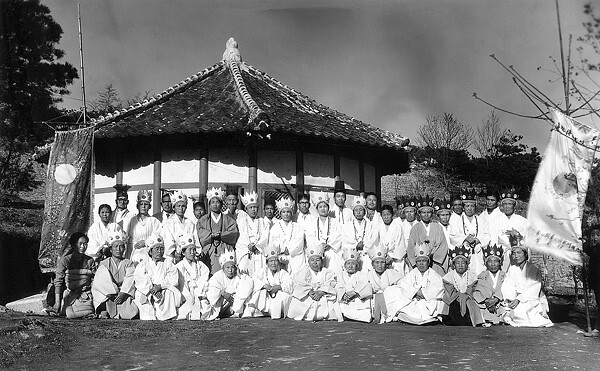

One of Sindoan’s religious organizations in the 1960s.

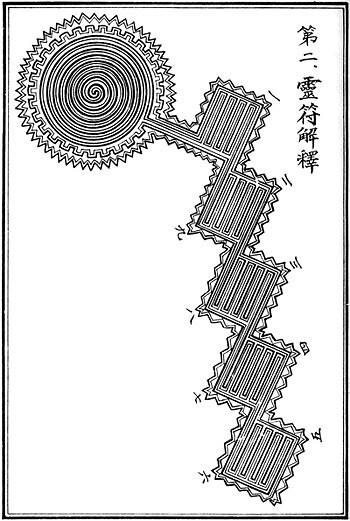

At this point, it is necessary to recall a historical fact. Korea’s traditional religious cultures, such as shamanism and Taoism, as well as new national religions from the turn of the twentieth century, were suppressed throughout the Japanese colonial and modern periods, not to mention during the era of the Joseon Dynasty, which adopted Confucianism as its national religion. In the wake of Westernization and globalization, folk beliefs and traditional religions are now viewed simply as tourist attractions or products of mysticism. As a result, we are used to critiquing Korean folk beliefs, new religions, mountain worship, and so forth, using the standard of more sophisticated dogmas. I do not particularly believe that the standard per se is distorted, yet there is a deep-rooted popular impression that prayer is purer than incantation, that religious symbols are more logical than shamanistic talismans, and that Christian hymns are more sophisticated than sutras. Sangje (“ruler above”) is a literal translation of “God,” but the latter has assumed a position superior to the former, just as wine has become the so-called well-being beverage, preferred over makkulli (unrefined Korean rice wine). In actuality, however, the majority of the institutional religions that have undergone rapid growth in South Korea in the last hundred years have unabashedly utilized prayer for good fortune and mystical experience, for grudge-soothing and ecstasy. In the fields of religious studies and folk cultural studies in South Korea, it is well known that shamanistic beliefs have been absorbed by Christianity and other religions, and have given birth to a peculiarly Korean religious culture strongly tinged with mysticism.

The more that religions originating from abroad utilize local traditions, the more it becomes necessary for them to distinguish themselves from “superstitions.” And when these religions endlessly attempt to define themselves as distinct from superstitions, the local beliefs—Heaven on Earth, tiger, mountain spirit, Sangje, Great King Yeomra, Medicine Buddha, and numerous other sacred beings—remain alive and well in the midst of their “counter-superstition.”8 Here we find the possibility of inverting the situation. Rather than see traditional folk beliefs as having been transformed and reduced by the Westernization of spirit, wouldn’t it be more accurate to see the whole process of transformation as an innovative way of dealing with things on the part of those whose traditional beliefs are under threat?

4.

If there is religion on the other side of modern science and technology, there is superstition on the other side of religion. I do not like modern science and technology, nor do I like organized religion. That doesn’t mean I can follow “superstitions.” The materialist’s cool brain is not really my thing either. Nevertheless, I like religion when it warns against the dangers of modern science and technology. I like superstitions that touch upon the unconscious of religions. I also like rational thinking when it rejects superstitions. For me, Mount Gyeryong stands proudly, or vaguely, in the midst of this kind of thinking.

Talisman of Donghak, Donghak Cheonjin-gyo.

I do not believe that this attitude is exclusively mine. Baridegi, Donghak and its Sangje, Cheongsan Geosa, and the ghosts in our grandmothers’ stories are not mere leftovers that modern cultures have made a point of “tolerating,” but could very well be sources of anxiety that shake the very foundations of those cultures. The contradictory figure of Northeast Asian Gothic culture is, in a sense, unavoidable. It is difficult to compare the structure of mythological narratives in which humans converse with wild animals with the ethics of mass genocide. Of course, because of its inherent mysticism, the culture of mythological narratives falls, over and over again, into the most corrupt forms of capitalism. But in the worst cases, even the politics of the most devious heresies are entangled in far more complex motivations and values than can be judged by a simple rationalist yardstick. There are no grounds for excusing the behavior of such sinister cults. Nevertheless, the phenomenon of cults is distinct from the universal human desire to seek utopia. Cult groups take advantage of the fact that this society is not equipped with the means to satisfy that very desire. Although a collective search for utopia can easily become corrupt and dangerous, the dream nevertheless belongs to everyone. There have always been, and will always be, great figures who could do nothing but claim the right to have this dream or be driven out trying. Is there really so much distance between Henri de Saint-Simon and Suwun Choi Je-wu? To me, Ilbu Kim Hang and Charles Fourier seem to resemble each other.9 Of the many people who were deprived of opportunities for institutional education or universal happiness, those who were particularly intelligent or fell into metaphysical agony went to Mount Gyeryong, Mount Jiri, or Mount Myohyang.10 Many of them were genuine, while many others were fake. What we need to examine first, however, is the contemporary urban dweller’s dull desire to distinguish easily between truths and lies, facts and fantasies. The sublime is something that can be discussed with regard to not only Barnett Newman’s paintings but also the quasi-Romantic images used for ideological purposes by North Korea, the war aesthetics of CNN, Hollywood’s disaster images, and terrorism’s political sublime. If the sublime is an aesthetic at risk, it can also be the aesthetic of a misfortune turned into a blessing. A variety of folk beliefs, traditional religions, and new religions prospered in Sindoan, in the foothills of Mount Gyeryong.11 They were all eclipsed in the 1970s and 1980s by the New Community Movement and the relocation there of the Gyeryongdae Joint Forces headquarters. There are no longer gods flying in the sky; instead, almost every hour, the sonic booms of fighter jets reverberate. There is no room left for mysticism, romanticism, and idealism. Yet I am attracted to the fact that this undeniable absence still gives us a shock. This is an encounter with something. It is not an encounter with a reality that is assumed to be there, and that can be revealed merely by overcoming “false consciousness.” Rather, it is an encounter with the violence accompanying the strange absence of a reality that is presumed to be there.

(Unless otherwise noted, this and all subsequent notes are the translator’s.) The mass of the forty-ninth day is so named because it is conducted on the forty-ninth day after someone dies. Originally a Buddhist rite, the mass is based on the belief that the soul of a dead person wanders without a body for forty-nine days until it reincarnates. In present-day Korea, the mass is widely practiced not only by Buddhists but also by people of various religious affiliations as well as by secularists.

Yoo Hong-jun is a well-known art historian, who also served as the head of the Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea from 2004 until 2008. In 1993 he published the first volume of My Survey of Cultural Heritages (Naeu munhwa dabsagi), a travelogue / personal reflection for general readership, which contends that there are numerous unrecognized cultural artifacts all over Korea. The book became an instant best seller and led to the publication of two additional volumes, selling approximately 2.2 million copies total.

Kim Ji-ha is perhaps best known for his poem “Five Enemies” (Ojeok). Published in the May 1970 issue of the journal Sasanggye (Realm of Philosophy), the poem is a trenchant critique and parody of the corrupt government of the time, and Kim was ultimately convicted of violating the National Security Law and imprisoned for 100 days. Haewol is the sobriquet of Choi Shi-hyung, the second head of the Donghak (Eastern Learning) movement (see note 7 below). Haewol Philosophy refers to Choi’s interpretation of Donghak, which was organized for easy practice by the commoners and peasants who made up the majority of its followers. Choi In-hoon is considered one of the representative figures in modern Korean literature and is known for his existentialist works. For instance, his 1960 novel The Square (Gwangjang) portrays a young intellectual who struggles and then fails to find a third, alternative ideology to the binaries of North and South Korea, communism and capitalism, and eventually chooses to commit suicide.

Novelist Kim Seong-dong debuted in 1978 with his story “Mandala” (Mandara), which was published in the journal Korean Literature (Hanguk munhak). He also won that year’s New Writer Award. Published in a revised and expanded form in 1980, the story tells of the struggles and confusions of a young practicing Buddhist monk who comes to enlightenment by realizing that the true path lies not in solitary meditation but in encounters and relationships between people. It was later adapted for a film by Im Kwon-taek. One of South Korea’s most renowned directors, Im Kwon-taek has since 1962 made more than one hundred films, often set in Korea’s past and addressing the issue of Korean cultural identity in modernity. His films have been widely screened at international film festivals, and both he and his films have been honored with a number of awards, including Best Director for Chihwaseon (2002) at the Cannes Film Festival and Honorary Golden Berlin Bear at the Berlin Film Festival (2005).

Painter Park Saeng-Gwang, trained in Japan in Nihonga or modern Japanese-style painting during the colonial period, was often criticized in his early career for the “Japanese colors” in his work. In the late 1970s, he started traveling around the country to study traditional architectural and artistic traditions and subsequently devoted the rest of his life to developing a native Korean aesthetics. Oh Yoon is an artist best known for his woodblock prints, which often feature thickly contoured, rough figural representations of farmers, workers, and dancers in dynamic compositions. He is considered to be one of the most representative artists associated with the 1980s Minjung (people’s) Art movement. Painter Min Jeong-gi was first active as a member of the artists’ collective Reality and Utterance in the early 1980s and was also affiliated with the Minjung Art movement. His earlier paintings often employed kitschy figurative images as a way of expressing everyday social contradictions. Since the 1990s, he has focused on landscapes, in which he combines his intense observation of the Korean conceptual landscape painting tradition with Western oil painting techniques.

Writer Lee Moon-yeol is perhaps best known for his 1987 novel Our Twisted Hero (Urideul ui ilgeureojin yeongwung), which deals with the issues of politics and authority through an allegorical tale of young grade-school students. The novel won Lee the prestigious Yi Sang Literary Award in 1987 and was also adapted for a 1992 film of the same title. Since the mid-1990s, Lee has emerged as a prominent conservative voice through his lectures, newspaper editorials, and literary works.

Donghak (Eastern Learning) is a Korean religion established by Choi Je-wu in the 1860s, as the increasingly corrupt and feeble Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) was in its last phase and foreign intrusions and influences in Korea and Northeast Asia escalated. Responding to both internal and external urgencies, Choi preached a belief in a monotheistic god of heaven, an idea that had long been part of the native Korean belief system. Although it can be seen as an example of early modern Korean nativism and nationalism, Donghak incorporated elements of other religions that originated abroad but were long established in Korea, such as Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism. It was as much a political philosophy as a religion, and advocated democracy, equality, and paradise on Earth, quickly gaining followers among the peasant class. Donghak soon became the ideological basis for peasant uprisings, and Choi was accused of inciting the guerrilla warfare that began in 1862; he was arrested and executed in 1894. The leadership was then assumed by Choi Shi-hyeong (see note 4). In the same year, a large-scale revolution broke out against the government and the ruling yangban (literati-bureaucrat) class, as well as against encroaching foreign presences in Korea, such as Christianity and Japan. Calling for social reform and expulsion of foreign influences, the revolt posed a serious threat to the Joseon Dynasty but was eventually defeated by the Japanese army and pro-Japanese forces. Despite its failure, the Donghak Peasant Revolution led to modern reform efforts and the establishment of the Korean Empire (1897–1910). At the same time, it became the direct cause of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) over control of the Korean Peninsula and of increasing Japanese influence, which resulted in the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910.

Great King Yeomra is the ruler of the underworld and the judge of the dead in Buddhist mythology. “Yeomra” is the Sino-Korean transliteration of the Sanskrit name Yama Raja (King Yama), and this wrathful and fearsome deity is often depicted in Buddhist paintings and on the entrance gates to temples. Medicine Buddha, or the Master of Healing, is the Northeast Asian manifestation of the Indian Bhaisajyaguru. In Mahayana Buddhism, Medicine Buddha is understood to represent the healing aspect of Sakyamuni, the historical Buddha.

On Choi Je-wu, see note 7. Kim Hang and Choi Je-wu were fellow students. His interpretation of Zhouyi (Korean: Jooyeok), also known as Yijing or the I Ching, or Book of Changes, became the foundation of modern Korean studies of the ancient Chinese classic.

Mount Jiri and Mount Myohyang are located, respectively, in southwestern South Korea and northwestern North Korea. Like Mount Gyeryong, the two mountains are considered to be imbued with sacred spirits.

(Author’s note) Sindoan: the name of a basin located in the foothills of Mount Gyeryong, facing in the direction of the city of Daejeon. Currently situated in the territory of Gyeryong City, Chungcheong South Province, Sindoan was selected by Lee Seong-gye, the founder and first king of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), to be the location of his new capital; its name literally means “the new capital.” Adherents of the traditional Pungsu-Docham (geomancy and Confucian divination) Theory, folk religions, and new religions believed the site was the center of a utopian society. Since the Japanese colonial period, hundreds of religious and cult organizations have flourished in Sindoan. In 1984, with the relocation of the South Korean Joint Forces headquarters to Gyeryong Base, the majority of residences and religious structures were demolished.

Category

Subject

Translated from the Korean by Doryun Chong.