In A Thousand and One Nights, missing his younger brother, King Shâh Zamân, King Shahrayâr invites him to visit him. While on the point of heading to his brother from his camp on the outskirts of his capital, King Shâh Zamân remembers something he had forgotten in his palace. He heads back and discovers that his wife is betraying him with a slave. He slaughters her and her partner. Then he heads to his brother. The latter notes his brother’s depression; he ascribes it erroneously to nostalgia on account of leaving his kingdom. When King Shahrayâr invites his brother to a hunting trip, the latter, still depressed, declines the invitation. “King Shâh Zamân passed his night in the palace and, next morning, when his brother had fared forth, he removed from his room and sat him down at one of the lattice-windows overlooking the pleasure grounds; and there he abode thinking with saddest thought over his wife’s betrayal …. And as he continued in this case lo! a postern of the palace, which was carefully kept private, swung open and out of it came twenty slave girls surrounding his brother’s wife, who was wondrous fair, a model of beauty and comeliness and symmetry and perfect loveliness and who paced with the grace of a gazelle … Thereupon Shâh Zamân drew back from the window, but he kept the bevy in sight, espying them from a place whence he could not be espied. They walked under the very lattice and advanced a little way into the garden till they came to a jetting fountain amiddlemost a great basin of water; then they stripped off their clothes and behold, ten of them were women, concubines of the King, and the other ten were white slaves. Then they all paired off, each with each: but the Queen, who was left alone, presently cried out in a loud voice, ‘Here to me, O my lord Saeed!’ and then sprang with a drop-leap from one of the trees a big slobbering blackamoor with rolling eyes which showed the whites, a truly hideous sight. He walked boldly up to her and threw his arms round her neck while she embraced him as warmly; then he bussed her and winding his legs round hers, as a button-loop clasps a button, he threw her and enjoyed her. On like wise did the other slaves with the girls till all had satisfied their passions, and they ceased not from kissing and clipping, coupling and carousing till day began to wane; when the Mamelukes rose from the damsels’ bosoms and the blackamoor slave dismounted from the Queen’s breast; the men resumed their disguises and all, except the Negro who swarmed up the tree, entered the palace and closed the postern-door as before.”1 Feeling then that what he underwent, betrayal, his betrayal by his wife, is not so rare—all the more since he had just committed it, belatedly, by voyeuristically persisting in espying his brother’s wife’s betrayal with a blackmoor, instead of leaving promptly as soon as he made the discovery—King Shâh Zamân regains some of his liveliness. When his brother returns from his trip and notices the change, he asks him about it. King Shâh Zamân confesses to his brother the cause of his previous depression. “By Allâh, had the case been mine, I would not have been satisfied without slaying a thousand women, and that way madness lies!” How little did King Shahrayâr know yet about madness when he heard the account by his brother of the latter wife’s betrayal! Slaying a thousand women for one, in an enraged, revengeful slaughter spree, all at the same time or else first tens then hundreds until the total was a thousand, is an excessive measure but not necessarily a mad sort of behavior. King Shâh Zamân ends up informing his brother of what he saw in the latter’s palace, and then King Shahrayâr gets a confirmation through a repeat of these events a few nights later: “At dawn they seated themselves at the lattice overlooking the pleasure grounds, when …” a loop of the events occurs—with, the way I (imagine that I) see it, the following two variants: the events occur at night; and the blackmoor does not go up the tree and disappear from view and the queen, the concubines and the male slaves do not resume their disguises and then enter the palace and close the postern door as before, but rather the queen, the blackmoor, the concubines and the male slaves persist in their “activity,” and it is King Shahrayâr who leaves2 (along with his brother?)—the king’s harem has become muharram (forbidden) to him! How come the king did not spring to action and slay then and there his wife, her sexual partner, and her companions? What rendered him unable to do so and to act that night as a serial killer, slaughtering a thousand women for a duration that’s equivalent in abstract terms to the time the scene of jouissance in the palace’s garden lasted before he left? Was it that the gestures and more generally the behavior that he witnessed on the part of his wife and his concubines were of the sort that is seen in nightmares and therefore imply that the king was then in the typical paralysis of the sleeping body? Did the inexorable manner in which the gestures were being repeated, their automatism induce the ineluctable notion that they will go on, this unconsciously dissuading the king from trying to interrupt them and kill the intimate transgressors? Yet again, how to kill his concubines when two of them were bent on stabbing themselves in the back, repeatedly, but failing to accomplish that, the knives again and again not reaching their respective backs, so that, paradoxically, they already seemed undead, to the other side of physical death, where such a compulsive suicidal gesture itself becomes some sort of immortal automatism? Shâh Zamân goes along with Shahrayâr in his decision to “overwander Allâh’s earth … till we find some one to whom the like calamity hath happened; and if we find none then will death be more welcome to us than life.”3 Did what the two royal brothers see in the palace’s garden at all prepare them for what they then encounter? As they found themselves outside the palace, did they not feel that their surroundings were out of the world and that they were now moving in an extension of the fantasmatic space they apprehended “in” the palace’s garden? While they rested after wayfaring by day and by night, “the sea brake with waves before them, and from it towered a black pillar, which grew and grew till it rose skywards …. Seeing it, they waxed fearful exceedingly and climbed to the top of the tree, which was a lofty; whence they gazed to see what might be the matter. And behold, it was a Jinni, huge of height … bearing on his head a coffer of crystal. He strode to land, wading through the deep, and, coming to the tree whereupon were the two kings, seated himself beneath it. He then set down the coffer on its bottom and out of it drew a casket, with seven padlocks of steel, which he unlocked with seven keys of steel he took from beside his thigh, and out of it a young lady to come was seen … The Jinni seated her under the tree by his side and looking at her said, ‘O choicest love of this heart of mine! O dame of noblest line, whom I snatched away on thy bride night that none might prevent me taking thy maidenhead or tumble thee before I did, and whom none save myself hath loved or hath enjoyed: O my sweetheart! I would lief sleep a little while.’ He then laid his head upon the lady’s thighs; and, stretching out his legs which extended down to the sea, slept …. Presently she raised her head towards the tree-top and saw the two Kings perched near the summit … she … said, ‘Stroke me a strong stroke … otherwise will I arouse and set upon you this Ifrit who shall slay you straightway.’ … At this, by reason of their sore dread of the Jinni, both did by her what she bade them do; and, when they had dismounted from her, she … then took from her pocket a purse and drew out a knotted string, whereon were strung five hundred and seventy seal rings, and asked, ‘Know ye what be these?’ They answered her saying, ‘We know not!’ Then quoth she; ‘These be the signets of five hundred and seventy men who have all futtered me upon the horns of this foul, this foolish, this filthy Ifrit; so give me also your two seal rings, ye pair of brothers.’”4 What would the scene of sexual betrayal in the garden have had to be for it to act as a transition from the frame story’s previously realistic narration to a marvelous one? A scene of jouissance. Back at his throne, the king had to assign someone who did not witness the scene of jouissance, for example his vizier, to kill any one of the participants in the orgy, preferably his wife, since for anyone who had witnessed the scene of lascivious automatism, the orgy of jouissance was virtually ongoing even when the participants had ostensibly resumed their conventional behavior. The vizier managed to apprehend the blackmoor and took him in chains to the queen’s closet, where he reprimanded Shahrayâr’s unfaithful wife in this manner: “See what a grace was seated on this brow … / This was your husband.… / Have you eyes?”5 At this point, she heard a voice in her head interject, “but fail to see,”6 and then another, unfamiliar voice ask, “What use then are your eyes?” moments before the vizier blinded her with his dagger. Then the latter resumed his questioning: “Could you on this fair mountain leave to feed, / And batten on this moor? Ha! have you eyes?”7 By the time he repeated the last words, she no longer had eyes. “You cannot call it love”8—it is jouissance. Once the vizier interrupted the (virtual) loop by killing Shahrayâr’s wife, Shahrayâr could act. “Then King Shahryâr took brand in hand and repairing to the Serraglio slew all the concubines and their Mamelukes.”9 Is one night of jouissance, for example the one Shahrayâr espied in the garden of his palace and which included so much compulsive repetition, tantamount to a thousand nights of desire? It appears to be so: “He [Shahrayâr] also sware himself by a binding oath that whatever wife he married he would abate her maidenhead at night and slay her next morning to make sure of his honour; ‘For,’ said he, ‘there never was nor is there one chaste woman upon the face of earth.’ … On this wise he continued for the space of three years; marrying a maiden every night and killing her the next morning …”10 Why not kill in one fell swoop all the women under his rule if “there never was nor is there one chaste woman upon the face of earth”? It is because the response of the king to the virtually endless repetition he apprehended (“they ceased not from kissing and clipping, coupling and carousing, till day began to wane …”—when the king [and his brother?] left) was bound to take the form of repetition, of compulsive repetition.11 After a thousand nights, it seemed that the king would no longer be able to repeat again, since “there remained not in the city a young person fit for carnal copulation. Presently the King ordered his Chief Wazîr … to bring him a virgin … and the Minister went forth and searched and found none …”12 Within the economy of the book, that form of repetition had at this point to be relayed by another form, albeit one still stamped with compulsion. “So he [the Chief Wazîr] returned home in sorrow and anxiety fearing for his life from the King. Now he had two daughters, Shahrazâd and Dunyâzâd …”13 Shahrazâd volunteers to be the next wife of the king. “When the King took her to his bed and fell to toying with her and wished to go in to her she wept; which made him ask, ‘What aileth thee?’ She replied, ‘O King of the age, I have a younger sister and lief would I take leave of her this night before I see the dawn.’ So he sent at once for Dunyâzâd and she came and kissed the ground between his hands, when he permitted her to take her seat near the foot of the couch. Then the King arose and did away with his bride’s maidenhead and the three fell asleep.”14 The king saw in his dream what he had already seen in the garden of the palace a thousand nights before: some figures that appeared from one perspective to be each composed of a couple engaging in sexual activity while covered, except for their faces, within the dress of one of the two participants, but appeared from another perspective, anamorphically, to be each a two-headed autoerotic monster—in the case of the garden obscenity this physical anamorphosis was conjoined to a temporal one between the childless king witnessing these jouissance-inducing composites and the yet to come sexually-polymorphous child who one day would, like Dunyâzâd, take his seat near the foot of the couch, seeing and hearing with his “own [hallucinating?] eyes” and ears the primal scene, his parents, Shahrayâr and Shahrazâd, engaged in sexual intercourse. Shahrayâr awoke with a start from his brief sleep. At “midnight Shahrazâd awoke and signaled to her sister Dunyâzâd, who sat up and said, ‘Allâh upon thee, O my sister, recite to us some new story, delightsome and delectable, wherewith to while away the waking hours of our latter night.’ ‘With joy and goodly gree,’ answered Shahrazâd, ‘if this pious and auspicious King permit me.’ ‘Tell on,’ quoth the King, who chanced to be sleepless and restless … [T]hus … began her recitations.”15 The “following night,” indeed the “following myriad nights,” Dunyâzâd, yet again present in the room with them, said “to her sister Shahrazâd, ‘O my sister, finish for us that story …;’ and she answered ‘With joy and goodly gree, if the King permit me.’ Then quoth the King, ‘Tell thy tale.’” Shahrazâd’s storytelling had to be such as to counter the king’s vow and his compulsion to repeat marrying a virgin every night and killing her the next morning, but also to integrate the repetition, now of a milder form, that of the nightly storytelling (and of the occasion for it, Dunyâzâd’s “Allâh upon thee, O my sister, recite to us …”). What is the sum of a night of jouissance, which is tantamount to a thousand nights of desire, and a night of desire? It is:a thousand and one nights. Yes, one way of reading A Thousand and One Nights’s title is to reckon that it refers to both the night of jouissance that the king espied in the garden of his palace, a night tantamount to a thousand nights of desire, and the messianic Night of storytelling by Shahrazâd, a night in which she told myriad stories—until the appearance of a child to the erstwhile childless king notwithstanding that his ostensible mother was at no point pregnant!16 Who wrote or narrated the frame story of A Thousand and One Nights, more specifically the scene of the orgy in the garden? Who is describing it? Is that description an adequate one? Is that how King Shahrayâr perceived it, if not hallucinated it? Is that how he reviewed it in his nightmares? For instance, did King Shahrayâr actually see what appeared to be twenty slave girls strip, discovering thus that ten of them were actually men? No; in one of his recurring nightmares, a postern of the palace, which was carefully kept private, swung open, and out of it came twenty slave girls surrounding his wife, and then what would nowadays be best described as a cinematic dissolve took place and ended with ten naked concubines and ten naked white male slaves. When Shahrayâr initially heard from his brother that the latter had espied Shahrayâr’s wife betraying her husband, he said, “O my brother, I would not give thee the lie in this matter, but I cannot credit it till I see it with mine own eyes.”17 He should have soon realized that in relation to some scenes, seeing with one’s own eyes is not enough, and that one has to be told what one saw by a visionary teller. I imagine the king, having ascertained her knack for, indeed greatness in storytelling, saying to Shahrazâd, whether sometime during the series of storytelling episodes or else after she finishes her narration and brings him one child or three children: “While I want you to tell me myriad stories, I also want you to describe to me, narrate to me my discovery of the betrayal of my wife. I can try to describe to you what I saw with my own eyes, but treat my description as only a patchy approximation of what I saw, for that is what I myself feel it is; provide me with a description of what I apprehended (in part by extrapolating from the effects of what I saw on me)—one that is deserving of what I saw and of the effects what I saw induced in me, and one concerning which I would feel: ‘[Today] while knowing perfectly well that it corresponds to the facts, I no longer know if it is real.’”18 If he still had eyes even after seeing with his “own eyes” such obscenity, it must be that, like some of the figures in Inci Eviner’s Harem, he repeatedly failed to accomplish what he intended to do, to reach his eyes with his hands in order to gouge them out and throw them away (whether from an attitude affined to the Christian one [“If your right eye causes you to sin, gouge it out and throw it away. It is better for you to lose one part of your body than for your whole body to be thrown into hell” (Matthew 5:29)], that is, to get rid of jouissance, or else because that gesture itself is [as in the case of Oedipus?] henceforth part of jouissance), because his hands were then guided neither by the physical eyes nor the “mind’s eye,” since both were then overwhelmed with jouissance to the detriment of their usual function. Was Shahrazâd able to reconstruct the events of that day from the reactions of the king to what he saw in the secluded garden of his palace as well as to the myriad stories that she told him during their messianically inordinate Night? Whatever the answer, a “night” is missing from A Thousand and One Nights,19 the one Shahrazâd should have spent narrating to Shahrayâr the events of the frame story, in particular what he witnessed in the garden of his palace on the night he discovered the betrayal of his wife—in the process narrating to him the occasion for her subsequent narration. Since the book we presently have does not include such a narration by Shahrazâd, one of the outstanding tasks in relation to A Thousand and One Nights has been not so much to do an audiovisual adaptation of various episodes of the work (as, for example, Pasolini did in his Arabian Nights, 1974), but to provide a fitting rendition if not of the entirety of the frame story then of the episode in the secluded garden that Shahrayâr apprehended. I consider that Eviner’s Harem is an artistic adaptation of the missing narration by Shahrazâd in A Thousand and One Nights.20 Yes, in her Harem Inci Eviner provides us with an audiovisual rendition neither of what the various Ottoman sultans would have seen (or might have fantasized) regarding their harems nor of what their Orientalist guests might have fantasized (or would have seen if, like Lady Mary Wortley Montagu [1689–1762], they were privileged enough to be granted access to the harem),21 but, unbeknownst to her, of what King Shahrayâr of A Thousand and One Nightsapprehended one day in the secluded garden of his palace. Fittingly, both Eviner’s Haremand the palace garden’s scene of the frame story in A Thousand and One Nights unfold in two acts: regarding the harem of A Thousand and One Nights’s frame story, “a postern of the palace, which was carefully kept private, swung open and out of it came twenty slave girls surrounding his brother’s wife, who was … a model of beauty and comeliness and symmetry and perfect loveliness and who paced with the grace of a gazelle …. then they [the twenty] stripped off their clothes and behold, ten of them were women, concubines of the King, and the other ten were white slaves. Then … the Queen … cried out in a loud voice, ‘Here to me, O my lord Saeed!’ and then sprang with a drop-leap from one of the trees a big slobbering blackamoor with rolling eyes which showed the whites, a truly hideous sight. He … bussed her and winding his legs round hers, as a button-loop clasps a button, he threw her and enjoyed her. On like wise did the other slaves with the girls … and they ceased not from kissing and clipping, coupling and carousing …”; and Eviner’s Harem begins with a video shot of Antoine-Ignace Melling’s Intérieur d’une partie du harem du Grand Seigneur (Inside the Harem of the Sultan; watercolor and ink heightened with white gouach; from Voyage pittoresque de Constantinople et des rives du Bosphore, an album Melling [1763–1831] made when visiting Istanbul upon the invitation of Sultan Selim the Third)22 to then dissolve to her rendition of the figures engaged in various lascivious, compulsive gestures—when, following the jouissance in Eviner’s singular contribution, we see the original Melling work again as a result of the loop, the latter seems to be a (Freudian) screen memory.23 At one level, what the king watched in the secluded garden of his palace was somewhat akin to what a twentieth or twenty-first century spectator might watch in a gallery or museum: a loop—in the case of the king, the loop of jouissance.24 Very few works require intrinsically (rather than expediently, thus extrinsically) to be looped;25 Eviner’s Harem is one of these few, since its figures’ gestures are subject to the repetition compulsion. It itself may very well induce in its viewers a compulsion to repeat … viewing it (as happened to Chris Marker regarding that great film revolving around repetition, more precisely the compulsion to repeat, Hitchcock’s Vertigo, which he reported years ago having watched nineteen times)—as well as other things? Is Inci Eviner’s Harem, this work exhibiting jouissance, itself something that should not be witnessed—at least not by those uninitiated in Evil (one will not enter, one cannot enter hell with desires, however flagrant they may be; one can, indeed one is bound to “find” oneself in hell through jouissance)26? If so, then it would be a work whose title does not refer primarily to a historical harem but is self-referential: what is forbidden to vision is Eviner’s Harem. From Melling’s Intérieurd’une partie du harem du Grand Seigneur to Eviner’s Harem, the (primary) meaning of “harem” changes, from seraglio (The Redhouse Turkish-English Dictionary) to one that is closer to its Arabic etymology (“harem: Turkish, from Arabic … harama, to prohibit; seehrm in Semitic roots” [American Heritage Dictionary, 4th edition]), more specifically to the Arabic muharram (forbidden, prohibited, or made unlawful).27 In Eviner’s Harem, while the following inscription can be read on one placard, “Lady Montagu was here,” another inscription can be read on a second placard: “There’s a smear on the wall.” Whereas the inclusion of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who accompanied her husband to Adrianople and Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1717 following his appointment in 1716 as Ambassador to the Ottoman Court, and some of whose letters are collected under the titleThe Turkish Embassy Letters, in Melling’s Intérieur d’une partie du harem du Grand Seigneur would have been seemly, her inclusion in Eviner’s harem can be considered a smear campaign, since the one who wrote the sort of letters that Lady Mary Wortley Montagu penned cannot have been in the latter surroundings. If there is a smear on the wall, if there is a stain (can there be jouissance without a stain? Is jouissance itself the stain?), a blot on the wall, then it is Eviner’s Harem itself, for example while being screened at Nev gallery in Istanbul.

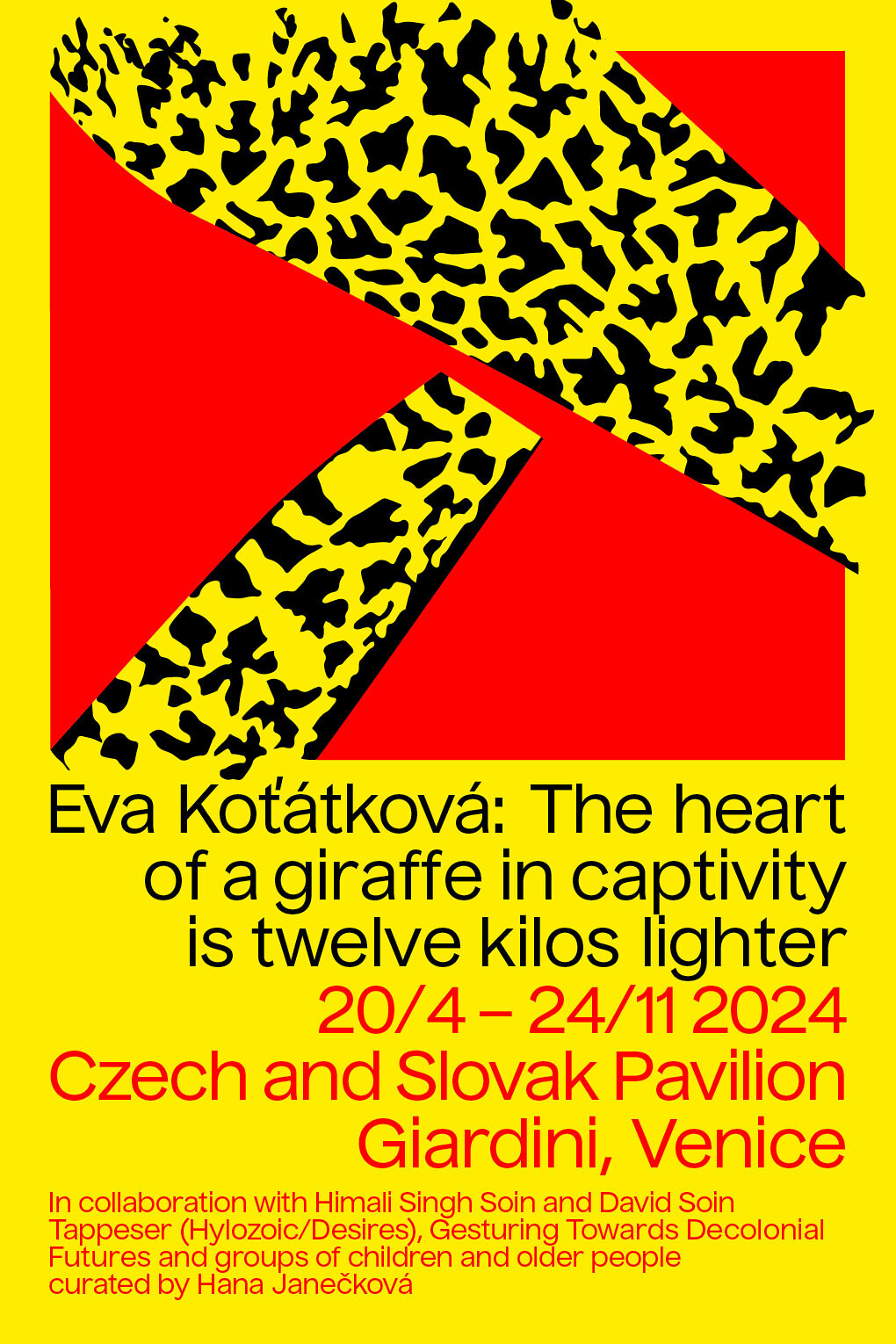

Inci Eviner, Harem, 2009, single channel video loop, 3 min., color.

Deleuze: “In a way, Bacon has hystericized all the elements of Velásquez’s painting [Pope Innocent X].… In Velásquez, the armchair already delineates the prison of the parallelepiped; the heavy curtain in back is already tending to move up front, and the mantelet has aspects of a side of beef; an unreadable yet clear parchment is in the hand, and the attentive, fixed eye of the Pope already sees something invisible looming up. But all of this is strangely restrained; it is something that is going to happen, but has not yet acquired the ineluctable, irrepressible presence of Bacon’s newspapers, the almost animal-like armchairs, the curtain up front, the brute meat, and the screaming mouth. Should these presences have been let loose? asks Bacon. Were not things better, infinitely better, in Velásquez? In refusing both the figurative path and the abstract path, was it necessary to display this relationship between hysteria and painting in full view? While our eye is enchanted with the two Innocent Xs, Bacon questions himself.”28 Did Inci Eviner question herself as she “hystericized all the elements of” Antoine-Ignace Melling’s Intérieur d’une partie du harem du Grand Seigneur in Harem? Will she, who has in her Harem already overridden the “human, all too human,” question herself in time, while she has not yet surrendered to jouissance, but is still exploring (“explore: ORIGIN mid 16th cent. [in the sense (investigate [why])]: from French explorer, from Latin explorare ‘search out,’from ex- ‘out’ + plorare ‘utter a cry’”)29 it? Are there many artists and filmmakers since Bacon’s 1962 interview with David Sylvester, referred to in the aforementioned Deleuze quote, who have been questioning themselves about this matter? It does not appear to be the case. Did David Lynch question himself when the angel disappeared from the painting in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), a disappearance that’s in relation not only to what the protagonist, Laura Palmer, was undergoing, but also to the film itself (was not the reappearance of the angel in the coda at one level a way for Lynch to assuage—artificially?—any misgivings or second thoughts he might have had about his film?)? Was the angel’s leaving not a sign for the film spectators, albeit a subtle one since seemingly applying within the diegesis, to beware of, if not stop watching the remainder of that film as well as Lynch’s subsequent films (Inland Empire, 2006 …)—until the possible reappearance of the angel? Those spectators who do not leave with the angel are ignoring or forgetting what Freud informed us about: that “it is a prominent feature of unconscious processes that they are indestructible. In the unconscious nothing can be brought to an end, nothing is past or forgotten,”30 so that images of jouissance subsist in the unconscious even when it seems to us that we have long forgotten them; and that in the unconscious, as in magic, there is an equation of image and thing. Were the images of jouissance we saw in a horror film to enter our dreams, which are compromise formations, can we be sure that the psychic apparatus will subsequently be able to discern from where they were borrowed? Is it not possible that it will refer these horrifying images, which, while coming from consensual reality, have many of the characteristics of the primary process, to the unconscious? What then? Then they would affect us no differently than actual crimes, slaughters, beheadings we might have witnessed (when?) in our lives. How many bourgeois students who have never been to a war have an unconscious filled with more horrifying images than that of a soldier in the trenches of the battles of World War I! Most people are less and less “willing” to take risks in this world; meanwhile they are, most often unbeknownst to them, more and more tolerant of taking risks in the barzakh/bardo! It is certainly wiser to have the opposite attitude. When someone reduced to the material world, the dense world, entreats God, “Ultuf!”, he or she means by it: be kind to us; alleviate our condition—in the sense: make it less severe. But ultuf, as well as “alleviate our condition,” should also and primarily mean: make us subtle, make us concerned with the subtle, Imaginal World (‘âlam al-khayâl), and, moreover, spare us the worst in the subtle, Imaginal World, for it is there that one encounters the worst, recurrently. The “human, all too human” is not enough; does this mean that we should go all the way in the direction of jouissance? Or can we go in another direction, a more difficult one in the present circumstances: joy? Yes, against jouissance, let us not inadequately set the “human, all too human,” but rather let us invoke and/or create joy. One of the main issues and tasks of our time that has unleashed on us what strikes directly the libidinal system, jouissance, is to attain joy, what touches directly the soul. Let us invoke and/or create the excessive against the excessive, the inhuman against the inhuman, the angelic against the demonic, in other words, the overwhelming (Rilke: “Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’ / Hierarchies? and even if one of them pressed me / suddenly against his heart: I would be consumed / in that overwhelming existence.…”)31 against the overwhelming, Good against Evil (for as long as we are mortal, that is, dead even while alive, we cannot, notwithstanding Nietzsche’s behest to do that, fully replace Good and Evil by good and bad—we can at most ignore if not repress Good and Evil by being oblivious about our mortality and that we have not yet reached the will, which is a manner of doing away with mortality),32 rather than attempt to set the moralizing good against Evil when that sort of good can be set only against the bad (the angels of Wenders’ Wings of Desire, 1987, who, but for the absence of the interior monologue, are “human, all too human,” can assist humans against the bad, but they cannot do so against Evil).

Obsessed and haunted by Velásquez’s painting Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650), Bacon must have tried to render it in such a manner as to make paint come “across directly onto the nervous system,”33 in other words, “bring the figurative thing up onto the nervous system more violently and more poignantly.”34 For someone wishing to achieve this but probably not yet fully prepared (is one ever fully prepared?) for the successful outcome, did he have the impulse to hide the figure? 35 Where? Behind the red drapery in back of the pope? He may have tried to do so—without success, for a figure that “comes across directly onto the nervous system” and/or that is overcome with jouissance cannot be hidden by a curtain, especially when the paint in which the latter is rendered itself “comes across directly onto the nervous system.”36 Can one alternatively cover such a figure with paint, overpaint it (to use an Arnulf Rainer term)? Yes, but this is not enough—as, incidentally, modern radiography, including x-ray, would have somewhat revealed (by the way, have any x-rays been done of Arnulf Rainer’s Overpaintings? If not, this would confirm how little thought goes into the selection of which works to submit to such a process). Perhaps these figures that cannot be hidden behind the curtain can—along with the curtain (“quantum”) tunneling across them—only be hidden on a canvas whose rear is to us. Francis Bacon: “This is the obsession: How like can I make this thing in the most irrational way? So that you’re not only remaking the look of the image, you’re remaking all the areas of feeling which you yourself have apprehensions of. You want to open up so many levels of feeling if possible, which can’t be done in …. It’s wrong to say it can’t be done in pure illustration, in purely figurative terms, because of course it has been done. It has been done in Velázquez.… one wants to do this thing of just walking along the edge of the precipice, and in Velázquez it’s a very, very extraordinary thing that he has been able to keep it so near to what we call illustration and at the same time so deeply unlock the greatest and deepest things that man can feel.”37 But we can view Velázquez’s painting Las Meninas (1656) as comprising all three of the possibilities mentioned by Bacon: while the paintings on the wall in the background, which were based on copies by Juan del Mazo after some Rubens works, are rendered in an illustrative way by Velásquez, he “has been able to keep” the rest of the visible painting “so near to what we call illustration and at the same time so deeply unlock the greatest and deepest things that man can feel,” and he has been able to paint what “comes across directly onto the nervous system” or the structure in which the latter can irrupt and to keep it invisible to us by reserving it to the canvas, represented illustratively, whose rear is to us. I would title the invisible painting on the canvas whose rear is to us in Velásquez’s Las Meninas: Harem or Muharram. If it is a portrait of the king and queen, then, unlike the figures of the king and queen as they appear in the mirror in the background, which are painted in an illustrative way, their own portraits would have become muharram (forbidden) to them. If it is not a portrait of the king and queen, then I would like to think that Velásquez was so sensitive that having made Portrait of Pope Innocent X he had to make a painting that includes a canvas whose rear is to us, to accommodate what was virtually in his Portrait of Pope Innocent X; in this case, his two paintings Portrait of Pope Innocent X and Las Meninas can be viewed as a diptych. Is the painter represented in Las Meninas observing once more the king and the queen, to finish painting them, or is he looking away from something on the canvas that’s in front of him but whose rear is to us? What might that be? Something anxiety-inducing? Something silly? It is both: it is something anxiety-inducing placed in a context where it is so out of place that it becomes silly, indeed very silly. “Francis Bacon: ‘I don’t think that any of these things that I’ve done from other paintings actually have ever worked.’ David Sylvester: ‘Not even any of the versions of the Velásquez Pope?’ Francis Bacon: ‘I’ve always thought that this was one of the greatest paintings in the world, and I’ve used it through obsession. And I’ve tried very, very unsuccessfully to do certain records of it—distorted records. I regret them, because I think they’re very silly.’”38 Notwithstanding Bacon’s sweeping judgment, the resultant paintings are not silly in themselves—otherwise Bacon would have destroyed them the same way he destroyed many others when he considered that they were not successful. Bacon’s Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953) and Head VI (1949) are great paintings; if they can nonetheless be viewed as very silly, this would be not in comparison to Portrait of Pope Innocent X but in the context of Las Meninas. It is peculiar that no film, whether a biography of Velásquez or not, has been made in which the painting Las Meninas is remade as a tableau vivant and the camera does a traveling and reveals to us what is to the other side of the canvas. Francis Bacon: “I think I even might make a film …”;39 it is regrettable that he didn’t make a film, one where he would have been able to accomplish the aforementioned traveling shot since he could have provided the painting on the canvas whose rear is originally to us.40

Inci Eviner, Harem, 2009, single channel video loop, 3 min., color.

According to Genesis (22:1–2): “God tested Abraham. He said to him, ‘Abraham!’ ‘Here I am,’ he replied. Then God said, ‘Take your son, your only son, Isaac, whom you love, and go to the region of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains I will tell you about.’” According to the Qur’ân (37:99–106): “We gave him [Abraham] tidings of a gentle son. And when (his son) was old enough to walk with him, (Abraham) said: O my dear son, I have seen in a dream that I must sacrifice thee. So look, what thinkest thou? He said: O my father! Do that which thou art commanded. Allâh willing, thou shalt find me of the steadfast. Then, when they had both surrendered (to Allâh), and he had flung him down upon his face, We called unto him: O Abraham, you believed what you saw. Lo! thus do We reward the good. Lo! that verily was a clear test. Then We ransomed him with a tremendous victim.” I reckon that in Chapter VII of his The Interpretation of Dreams, titled “The Forgetting of Dreams,” Freud ignores or forgets one form of the forgetting of dreams: not forgetting a smaller or larger part of the content of the dream, but forgetting that a certain image, command, warning or request came to one in a dream. One of the most remarkable examples of such a forgetting of the dream is encountered in the Biblical version of God’s command to Abraham to sacrifice his son. Either there was one testing episode of Abraham concerning God’s command to him to sacrifice his son, and it got distorted in the Bible accessible to us, and the correct matter was later revealed to Muhammad through wahy, direct divine inspiration, as it was also revealed to him in this manner in the case of some other Biblical episodes (“We do relate unto thee [Muhammad] the most beautiful of stories, in that We reveal to thee this [portion of the] Qur’ân: before this, thou too was among those who knew it not” [Qur’ân 12:3, trans. Yusufali]); or else there were two episodes of testing of Abraham concerning God’s command to him to sacrifice his son, one reported in the Bible and one reported in the Qur’ân, each applying to one of Abraham’s two sons—in which case, Abraham would be common to Judaism and Islam not so much through similarity but through complementarity. In case there was only one such test, it is the following. Shortly before Sarah became pregnant, Abraham was asked by God in a dream to sacrifice his son (Qur’ân), his only son (Genesis 22:12 and 22:16) at that point, Ishmael (“Abram was eighty-six years old when Hagar bore him Ishmael” [Genesis 16:16] and “Abraham was a hundred years old when his son Isaac was born to him” [Genesis 21:5]).41 It is a mistake that can be quite dangerous not to interpret a dream but to try to execute literally what is demanded in it. Ibn al-‘Arabî: “Abraham the Intimate said to his son, I saw in sleep that I was killing you for sacrifice. The state of sleep is the plane of the Imagination and Abraham did not interpret [what he saw], for it was a ram that appeared in the form of Abraham’s son in the dream, while Abraham believed what he saw [at face value]. So his Lord rescued his son from Abraham’s misapprehension by the Great Sacrifice [of the ram], which was the true expression of his vision with God…. In reality it was not a ransom in God’s sight [but the sacrifice itself].… Then God says, This is indeed a clear test …”42 Why did Abraham not interpret the dream? Was it because he was unaware that dreams have to be interpreted? According to Ibn al-‘Arabî, “Abraham knew that the perspective of the Imagination required interpretation, but was heedless [on this occasion] and did not deal with the perspective in the proper way. Thus, he believed the vision as he saw it.”43 Why if Abraham knew that dreams are to be interpreted did he not do so? Could it be that he had not yet awakened, and thus treated the dream at face value? Did Abraham head to kill his son Ishmael while sleepwalking? Why did Abraham extend his dream—at the risk of killing his son? Was Abraham yielding unconsciously to his wife Sarah’s wish by not awakening, by continuing to dream? What was Sarah’s conscious wish? It was to get rid of Ishmael; she had said to Abraham, “Get rid of that slave woman and her son, for that slave woman’s son will never share in the inheritance with my son Isaac” [Genesis 21:10]). What was her more or less unconscious wish? It was that Ishmael be killed or be made to die as soon as possible. Abraham had already yielded once to Sarah’s wish, when he gave food and a skin of water to Hagar and sent her off with the boy. Had God not miraculously provided a well for Hagar and her son, they would have perished of thirst (“When the water in the skin was gone, she put the boy under one of the bushes. Then she went off and sat down nearby, about a bowshot away, for she thought, ‘I cannot watch the boy die.’ And as she sat there nearby, she began to sob. God heard the boy crying … Then God opened her eyes and she saw a well of water” [Genesis 21:15–19]). Again, was Abraham yielding unconsciously to Sarah’s more or less unconscious wish by not awakening, by continuing to sleep, in order not to interpret the dream but actualize it literally, that is, kill Ishmael? Given the untoward behavior of his father and the three-day-long trip, did Ishmael soon after their reaching their destination fall asleep? And did he then dream that his father told him, “Son, can’t you see that I am still sleeping and dreaming?”? Feeling guilty, Abraham confessed to his son in the dream; through this confession a part of Abraham was indirectly entreating his son to rectify the anomaly. Was Ishmael awakened, indeed jolted into wakefulness by this dream? And did he then try to awaken his ostensibly awake father? Was he successful? Yes. How? Allâha‘lam (God knows best). Once more God intervened so that Ishmael would not die; God did so again in part by opening the eyes of one of the parents of Ishmael, in this case Abraham’s ostensibly already open eyes. Now that Abraham was awake, he was aware again of what he already knew, that a dream should be interpreted. And at that point, given that this dream was not a purely personal one, but a divinely inspired one, God provided the interpretation, including materially: the ram to be sacrificed. In case there was one test of Abraham concerning God’s command to him to sacrifice his son, then there appears to be a tahrîf, an alteration in the Bible that’s available to us, since according to the latter God’s command to Abraham does not reach the latter in a dream and the concerned son is Isaac instead of Ishmael. And yet, not only does this alteration in the Bible to which we have access leave a trace in the same episode, where the dream that was deleted is nonetheless implied through the dreamlike condensation of two elements: Isaac and the (one who for a while was the) only son, Ishmael; there’s also a return of the repressed, the dream, and therefore of the relevance, indeed necessity of interpretation hidden in the Biblical story of God’s command to Abraham to sacrifice his son in an episode of Isaac’s old age in the same book. “When Isaac was old and his eyes were so weak that he could no longer see”—that is, when his eyes were like those of a sleeping man—“he called for Esau his older son and said to him, … ‘I am now an old man and don’t know the day of my death.… hunt some wild game for me. Prepare me the kind of tasty food I like and bring it to me to eat, so that I may give you my blessing before I die’” (Genesis 27:1–4). Isaac’s wife “Rebekah said to her son Jacob, ‘My son … : Go out to the flock and bring me two choice young goats, so I can prepare some tasty food for your father, just the way he likes it.’ Rebekah took the best clothes of Esau her older son, which she had in the house, and put them on her younger son Jacob. She also covered his hands and the smooth part of his neck with the goatskins” (Genesis 27:6–17). Does this not remind the reader of the substitution of a son by a ram in an earlier episode of the Bible, thus associating the two episodes? “Jacob went close to his father Isaac, who touched him and said, ‘The voice is the voice of Jacob, but the hands are the hands of Esau’” (Genesis 27:22). Encountering this condensation, a mechanism of the dream work, didn’t Isaac feel that he is dreaming? Do we not feel that we are encountering a dreamlike episode? Yes; the dream that was kept secret by being omitted in the Biblical episode of God’s command to Abraham to sacrifice his son returns surreptitiously in a scene of Isaac’s old age in the same book and then becomes manifest and gets confirmed in the Qur’ânic version (how confusing: while the Qur’ân corrects the version of the Bible that’s accessible to us, adding that the command was given in a dream, Abraham in the Qur’ân nonetheless does not treat the command as one that was given in a dream, therefore requiring interpretation!). Could old Isaac’s impression that he was dreaming have awakened him? Should he then not have tried to interpret what he was undergoing? For whatever reason, he didn’t. “He [Isaac] did not recognize him [as Jacob], for his hands were hairy like those of his brother Esau; so he blessed him” (Genesis 27:23). Were Isaac the one whom Abraham was commanded to sacrifice and who was ransomed with a ram, would he not have recalled that past episode of a substitution of a man by an animal when on touching the ostensibly hairy arm of his elder son, Esau, he heard the voice of Jacob? Symptomatically, the substitution of the elder son by the younger son,44 of Ishmael by Isaac, in the Biblical version of God’s command to Abraham to sacrifice his son is repeatedand condoned later in the Bible in the aforementioned episode of the old age of Isaac—as if the ones who had altered the text and done the substitution of the elder son by the younger son in Abraham’s story were thus condoning what they did. If there were two episodes of testing of Abraham concerning God’s command to him to sacrifice his son, then the second episode is the following. Abraham, who had ended up awakening in order to become aware of the necessity of interpreting the dream in which God commanded him to sacrifice his son Ishmael, was asked again to sacrifice a son. This time he was ostensibly not sleeping—and yet there was something dreamlike about what he was told by God: “Take your son, your only son, Isaac, whom you love, and go to the region of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains I will tell you about” (Genesis 22:1–2). How couldal-Haqq (The Truth, The Real [Qur’ân 6:62, 22:6, 23:116, 24:25 …]), al-‘Alîm (The Omniscient [Qur’ân 2:115, 2:282–283, 3:34, 5:97, 6:101, 29:62, 42:12 …]), al-Muhsî (The Accounter, The Encompasser [Qur’ân 72:28, 78:29 …]), al-Hâsib (The Reckoner [Qur’ân 4:86 …]) tell him, ‘Take your son, your only son, Isaac … ,” when he had two sons? The first dream’s content concerning sacrificing his son must have “made [such] an impression on” Abraham that he “proceeded to ‘re-dream’ it, that is, to repeat some of its elements”45 in a subsequent dream. And yet Abraham told himself that he was already awake, and that therefore God must be testing his faith—notwithstanding that the test of his faith was passed successfully by him already through his unwavering belief that God would grant him a child as promised however old he and Sarah would get. At their destination, Isaac asked his father, “The fire and wood are here, but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?” Abraham, remembering the earlier test he underwent with Ishmael, did not lie to his son when he answered hopefully, “God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son” (Genesis 22:7–8). Yet shortly after, God not telling him otherwise, Abraham bound his son and set the wood and started the fire. Hearing the voice of his son Isaac, the one who was not informed and consulted about his imminent sacrifice and therefore did not have the opportunity to possibly answer, “O my father! Do that which thou art commanded. Allâh willing, thou shalt find me of the steadfast” (Qur’ân 37:102), crying out, “Father, don’t you see that I am burning?”46 ostensibly awake Abraham awakened—from the dream that life is! How? How is the one who already woke up from sleep to awaken yet again? The prophet Muhammad gave an indication concerning this: “People are asleep, and when they die, they awake.” Since dying before dying physically is not some metaphorical death but death “itself,” and thus would involve a radical separation from his son, I understand that Abraham delayed it as much as possible, till the penultimate moment. Abraham would have preferred to kill himself physically, to commit suicide rather than sacrifice his son, that is, he would have preferred it had God asked him to sacrifice himself rather than his son; but given that God’s command was to sacrifice his son, the great believer that Abraham was did not kill himself physically rather than kill his son, but the loving father, the one who loved Isaac and Ishmael, and the conscientious man that he was died before dying physically at his destination rather than sacrifice his son Isaac without coming to terms with the dreamlike “Take your son, your only son, Isaac” and the requirement of interpretation it implies. Only if someone did not receive the command that requires what Kierkegaard terms the “teleological suspension of the ethical” (Fear and Trembling) in a dream or undergo while ostensibly awake one or more dreamlike episodes in the same period in which he received such a command is he or she to accomplish it without resorting to prerequisite interpretation. How many of those who were commanded to behead or otherwise slaughter someone ostensibly on behalf of their religion if not directly of their God, for example many of the members of al-Qâ‘ida in Iraq and elsewhere, did not undergo in the same period one or more dreamlike episodes while ostensibly awake? Did the others try to interpret what they underwent before choosing the “teleological suspension of the ethical”? The sleepwalkers of al-Qâ‘ida in Iraq and elsewhere certainly did not try to interpret the commands they received (after decoding those of them that reached them in encoded guises). Were Ibn al-‘Arabî, who reprimanded no less than a rasûl, a messenger-prophet, Abraham, for rushing to behead his son without interpreting the command,physically alive presently, I would not be surprised were the sleepwalkers of al-Qâ‘ida in Iraq and elsewhere, who are largely if not completely ignorant of his writings but who have blown up a number of Sufis in Iraq,47 to have tried to behead him. Once Abraham’s dream is interpreted, it is clear that the God of Islam does not demand, even as a test, that a prophet behead his son, whereas the God of the Bible (that’s accessible to us) does so as a test of Abraham’s faith in Kierkegaard’s Christian reading 48 as well as in Derrida’s (Jewish—at least in the sense of Biblical—) reading of the latter: “Is this heretical and paradoxical knight of faith Jewish, Christian, or Judeo-Christian-Islamic? … This rigor [where is the rigor in not interpreting a dream? Derrida had earlier written: “Kierkegaard quotes Luke 14:26 … He refines its rigor …”], and the exaggerated demands it entails, compel the knight of faith to say and do things that will appear (and must even be) atrocious. They will necessarily revolt those who profess allegiance to morality in general, to Judeo-Christian-Islamic morality …”49 To the one who awakens by dying before dying, God provides the interpretation of one or more episodes of the dream that life is. Again, Abraham was provided with the interpretation of the dream: the ram to be sacrificed. While by awakening by dying (before dying), Abraham extended the life of his son, at least for the span during which he would be provided by God with the interpretation of the dreamlike episode, he was not by doing so necessarily yielding to temptation, that of avoiding the “teleological suspension of the ethical,” since awakening did not mean automatically saving his son, but rather becoming aware of the exigency of interpreting what occurs to him in life as a dream, and waiting for the interpretation of that dream, which might have been even then: “Sacrifice him … as a burnt offering …” (Genesis 22:2). Again the interpretation revealed that a ram had appeared in the dream—that life is—in the guise of Abraham’s son Isaac. Should we take a hint from the image by Inci Eviner of two headless humans holding the severed head of a ram on a plate that either there were one episode of sacrifice of the ram or else, if there were two episodes, that it was the “same” great sacrifice, the same ram that was miraculously sacrificed? In the latter case, this sacrificial victim is great not only because of the greatness of what it replaced, a prophet, in a visionary dream if not in reality, but also because it did so twice, in the case of both Ishmael and Isaac.

The Arabian Nights: Tales from a Thousand and One Nights, translated, with a preface and notes, by Richard Francis Burton, introduction by A. S. Byatt (New York: Modern Library, 2001), 7–8.

While it may seem that I am altering A Thousand and One Nights, actually I am emending the text, not through historical, textual and/or archival research but through creative writing and thus untimely collaboration with one or more of its creators, restoring it partly to how it was before undergoing corruptions in the form of some of the interpolations and alterations and erasures it underwent during its long history.

The Arabian Nights: Tales from a Thousand and One Nights, 12.

Ibid., 12–14. Taking into account the parallelism between the two scenes (in both the two kings espy the events from a distance, at least initially, and in both they are privy to a woman’s unfaithfulness), it is reasonable to suspect that King Shahrayâr’s first wife was also captured by his army or abducted by his agents on the very night she was to be wed to another.

Prince Hamlet’s words to his mother in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (3.4.55–65).

Mark 8:18.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet 3.4.66–67.

Ibid. 3.4.68. Had the vizier exclaimed, “You cannot call it jouissance,” he would also have been right—not because it is not jouissance, but because jouissance is not open to the call. Romeo says to Juliet: “Call me but love …” (Shakespeare,Romeo and Juliet 2.1.92–94); no one can accurately write or say, “Call me but jouissance …” On the relation of love to the name and the call, read my book Graziella: The Corrected Edition (Forthcoming Books, 2009; available for download as a PDF file at →).

The Arabian Nights: Tales from a Thousand and One Nights, 15–16.

Ibid., 16.

The scene is itself repeated in A Thousand and One Nights, since it is first seen by Shâh Zamân, who ends up informing his brother King Shahrayâr about it, the two then witnessing it again. It would be intriguing to exhibit Inci Eviner’s Harem in the lobby of a film theater screening Lynch’s Lost Highway, the audience members witnessing the two dreadful extremes: repetition compulsion and exhaustive variation.

The Arabian Nights: Tales from a Thousand and One Nights, 16.

Ibid.

Ibid., 26.

Ibid.

I provide in my book Two or Three Things I’m Dying to Tell You (Sausalito, CA: The Post-Apollo Press, 2005) a variant but complementary manner of considering the title: The Thousand and One Nights “refers to … the one thousand nights of the one thousand unjustly murdered previous one-night wives of King Shahrayâr plus his night with Shahrazâd, a night that is itself like a thousand nights … We could not write were we as mortals not already dead even as we live; or else did we not draw, like Shahrazâd, in an untimely collaboration, on what the dead is undergoing. If Shahrazâd needed the previous deaths of the king’s former thousand one-night wives, it was because notwithstanding being a mortal, thus undead even as she lived, she did not draw on her death. That is why she cannot exclaim to Shahrayâr: ‘There’s something I am dying to tell you.’ And that is why past the Night spanning a thousand nights, Shahrazâd cannot extend her narration even for one additional normal night” (102). Both of my manners of considering the title are at variance with the widespread way it is read and according to which it refers to the number of nights Shahrazâd tells stories to Shahrayâr.

The Arabian Nights: Tales from a Thousand and One Nights, 11.

Charlotte Delbo, Days and Memory, translated and with a preface by Rosette Lamont (Marlboro, Vt.: Marlboro Press, 1990), 4.

On the missing night in A Thousand and One Nights, read “Something I’m Dying to Tell You, Lyn” in my book Two or Three Things I’m Dying to Tell You, 101–103: “Were I to become the editor of a future edition of The Thousand and One Nights, I would … make sure that one of the so-called nights is missing, i.e., that the edition is incomplete.… Since the ‘thousand nights’ of storytelling are the extension by Shahrazâd of one night, there is something messianic about The Thousand and One Nights. I gave my beloved Graziella a copy of The Thousand and One Nights in the Arabic edition of Dâr al-Mashriq, rather than in the Bûlâq edition republished by Madbûlî Bookstore, Cairo, certainly not because it is an expurgated edition, but because it does not contain at least one of the nights—night 365 is missing. ‘According to a superstition current in the Middle East in the late nineteenth century when Sir Richard Burton was writing, no one can read the whole text of the Arabian Nightswithout dying’ (Robert Irwin, The Arabian Nights: A Companion). Borges: ‘At home I have the seventeen volumes of Burton’s version (of The Thousand and One Nights). I know I’ll never read all of them …’ Until the worldly reappearance of al-Qâ’im (the Resurrector), there should not be a complete edition of The Thousand and One Nights. The only one who should write the missing night that brings the actual total of nights to a thousand and one is the messiah/al-Qâ’im, since only with his worldly reappearance can one read the whole book without dying.”

I therefore suggest that a DVD of Eviner’s Harem be attached to copies of A Thousand and One Nights.

Were it the case, there would be something amiss in Eviner’s rendition of the harem, since she would have omitted altogether the conservative religious members of the harem, their prayers and orthodox behavior and rituals.

See →, accessed, July 18, 2010.

To be more precise, the scene of undressing and sexual intercourse in the palace’s garden in A Thousand and One Nights enfolds two variants: one of desire, witnessed by both kings, and one of jouissance, fantasmatic, apprehended by Shahrayâr alone—this may in part account for why Shâh Zamân does not have a similar compulsive reaction as Shahrayâr.

Were it not for the last, angelic section of Patrick Bokanowski’s The Angel (1982), I can imagine screening this film in a museum as a loop—among other things, the angel guards against the compulsion to repeat, the loop.

When Predrag Pajdic wished to include my video The Lamentations Series: The Ninth Night and Day (60 minutes, 2005) as a looped work in one of the exhibitions and screenings he curated in various venues in London in the summer of 2007 (Tate Modern, etc.), I declined his request, insisting that the video should not be looped but rather screened in a movie theater at scheduled times since the repetition in this video is not of the compulsive sort and since this video is a durational work. In his “Ritualizing Life: Videos of Jalal Toufic,” Art Journal 66, no. 2 (Summer 2007): 83–84, Boris Groys ends his text with, “Already Nietzsche asserted that after the death of God, immortality can be imagined only as the eternal repetition of the same—as ritualized life. Contemporary video technique can be seen as a technical realization of this Nietzschean metaphysical dream. The videos of Toufic show time and again scenes of sleep, disappearance, and death. But their ritual character suggests the possibility of repetition that negates the definitive character of any loss, of any absence. Today, the only image of immortality that we are ready to believe is a video running in a loop,” notwithstanding that my video Lebanese Performance Art; Circle: Ecstatic; Class: Marginalized; Excerpt 3 (5 minutes, 2007) has the intertitle, “An Original Video Should Be Watched at Least Twice (Rather than Looped),” and that indeed the video proper, which is two minutes and ten seconds long, is then repeated; and notwithstanding that I had published in 2000 “You Said ‘Stay,’ So I Stayed” in my book Forthcoming (Berkeley, CA: Atelos, 2000), a text that provides a radically different reading of Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence in its relation to the will and thus to the abolishing of death and to one of the forms of the new.

For a different conception of hell, read my book Undying Love, or Love Dies (Sausalito, CA: The Post-Apollo Press, 2002; available for download as a PDF file at →).

Here are some of muharram’s other meaning: “made, or pronounced, sacred,or inviolable, or entitled to reverence or repect or honour” (The entry hâ’ râ’ mîmin Edward William Lane, An Arabic-English Lexicon, 8 volumes (Beirut, Lebanon: Librairie du Liban, 1980)).

Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, trans. Daniel W. Smith (London: Continuum, 2003), 53–54.

Apple’s Dictionary.

The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, volume V (1900–1901), The Interpretation of Dreams (Second Part) and On Dreams, translated from the German under the general editorship of James Strachey, in collaboration with Anna Freud, assisted by Alix Strachey and Alan Tyson (London: Vintage, the Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1953–1974), 577. Cf: “The unconscious is quite timeless. The most important as well as the strangest characteristic of psychical fixation is that all impressions are preserved, not only in the same form in which they were first received, but also in all the forms which they have adopted in their further developments.” Ibid., volume VI (1901), The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, 275.

The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, ed. and trans. Stephen Mitchell; with an introduction by Robert Hass (New York: Vintage Books, 1982), 151.

Read “You Said ‘Stay,’ So I Stayed” in my book Forthcoming.

David Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon, third, enlarged edition (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 1987), 18.

Ibid., 12.

Is one ever prepared for certain things one may have done the utmost to make possible, for example what “comes across directly onto the nervous system” or a successful resurrection? “Her eyelids ‘opened to reveal something terrible which I will not talk about, the most terrible look which a living being can receive, and I think that if I had shuddered at that instant, and if I had been afraid, everything would have been lost, but my tenderness was so great that I didn’t even think about the strangeness of what was happening, which certainly seemed to me altogether natural because of that infinite movement which drew me towards her’ (Blanchot’s Death Sentence). The far more frequent and regrettable phenomenon in these resurrections is that just as the eyes of the resurrector and those of the resurrected come into contact, and the resurrector sees in the latter a reflection of the dreadful realm where the resurrected was, he or she in horror instinctively closes the resurrected’s eyes. This, rather than shutting the eyes of the corpse, is the paradigmatic gesture of closing the dead’s eyes. Indeed, the gesture of closing the eyes of the corpse probably originated, at least in the Christian era, in witnessing someone hurriedly shutting the eyes of a dead person whom he had resurrected. Were humans one day to no longer believe in resurrection and to have forgotten it consequent of a withdrawal of the epoch when some people were resurrected, it is likely that they will no longer close the eyes of the corpse. I find it disappointing that none of the vampire films I have seen, and I presume no vampire film at all shows what is likely to take place during the initial encounter of the vampire with his living guest: what the guest apprehends in the undead’s eyes is so horrifying, he instinctively raises his hand toward the vampire’s eyes to close them, only to hear the vampire, who had already had to tackle this reaction numerous times, say: ‘Your arms feel very tired. You long to rest them against your hips.’ Hypnotized, the guest let his now very heavy hands fall down.” Jalal Toufic, (Vampires): An Uneasy Essay on the Undead in Film, revised and expanded edition (Sausalito, CA: The Post-Apollo Press, 2003, available for download as a PDF file at →), 219–220.

Were it not the case, then I can very well imagine that there is something hidden behind the drapery in Velásquez’s painting and that that something is Bacon’s pope in Study after Vélázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953). Could the pope of Velasquez have performed an exorcism of the pope of Bacon?

The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon, 28.

Ibid., 37.

Ibid., 141.

It is fitting that Godard did not include Las Meninas among the paintings Jerzy tries to do a tableau vivant of, for he, Godard, is incapable of presenting by creating what is to the other side of its represented canvas.

It is disappointing that the four brief scenarios that Kierkegaard gives of this test in the “Exordium” of his book Fear and Trembling all assume that awake Abraham was commanded by God to sacrifice his son Isaac, i.e., that Kierkegaard’s variations remained relative to one of the two mainstream versions, missing the other altogether. “There were countless generations who knew the story of Abraham by heart, word for word, but how many did it render sleepless?” (Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling and Repetition, edited and translated with introduction and notes by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), 28). It appears that Kierkegaard was one of those whom the story of Abraham rendered sleepless—this possibly deprived him of an additional opportunity to intuit that Abraham received the command to sacrifice his son in a dream; and it is manifest that he did not actually know the story word for word, since certain words were missing from the version he knew, for example: “in a dream”; and it seems that he was oblivious of (what the sufis term) the sirr (innermost, secret heart; secret). How little kashf (supersensory unveiling) Kierkegaard had; one can say the same of Derrida when he writes in a seemingly inclusive gesture, “The sacrifice of Isaac belongs to what one might just dare to call the common treasure, the terrifying secret of the mysterium tremendum that is a property of all three so-called religions of the Book, the religions of the races of Abraham” (Jacques Derrida, The Gift of Death, trans. David Wills (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 64), either ignorant or repressing his knowledge that the son Abraham was commanded to sacrifice has no specific name in one of these Books, that of Moslems, the Qur’ân; that according to Tabarî, “the earliest sages of our Prophet’s nation disagree about which of Abraham’s two sons it was that he was commanded to sacrifice. Some say it was Isaac, while others say it was Ishmael” (The History of al-Ṭabarî (Ta’rîkh al-rusul wa’l-mulûk), volume II, Prophets and Patriarchs, translated and annotated by William M. Brinner (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1987), 82; see pages 82–95 for the various traditions regarding which of the two sons Abraham was commanded to sacrifice); that Ibn Kathîr opts for Ishmael as the son Abraham was commanded to sacrifice (Al-imâm al-Hâfiz ‘Imâd al-Dîn Abî al-Fidâ’ Ismâ‘îl ibn Kathîr al-Qirashî al-Dimashqî, Qisas al-Anbiyâ’, ed. al-Sayyid al-Jumaylî (Beirut, Lebanon: Dâr al-Jîl, 2001), 155–160); and that in most later Islamic tradition Ishmael (Ismâ‘îl) is considered the son whom Abraham was commanded to sacrifice—in a dream.

Ibn al‘Arabi, “The Wisdom of Reality in the Word of Isaac,” in The Bezels of Wisdom, translation and introduction by R. W. J. Austin, preface by Titus Burckhardt (New York: Paulist Press, 1980), 99–100.

Ibid., 100.

Full disclosure: I am the elder son in my family.

The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, volume V (1900–1901), The Interpretation of Dreams (Second Part) and On Dreams, 509.

Sigmund Freud: “Among the dreams which have been reported to me by other people, there is one which … was told to me by a woman patient who had herself heard it in a lecture on dreams … Its content made an impression on the lady … and she proceeded to ‘re-dream’ it, that is, to repeat some of its elements in a dream of her own … The preliminaries to this model dream were as follows. A father had been watching beside his child’s sick-bed for days and nights on end. After the child had died, he went into the next room to lie down, but left the door open so that he could see from his bedroom into the room in which his child’s body was laid out, with tall candles standing round it. An old man had been engaged to keep watch over it, and sat beside the body murmuring prayers. After a few hours’ sleep, the father had a dream that his child was standing beside his bed, caught him by the arm and whispered to him reproachfully: ‘Father, don’t you see I’m burning?’ He woke up, noticed a bright glare of light from the next room, hurried into it and found that the old watchman had dropped off to sleep and that the wrappings and one of the arms of his beloved child’s dead body had been burned by a lighted candle that had fallen on them.… The explanation of this moving dream is simple enough and, so my patient told me, was correctly given by the lecturer. The glare of light shone through the open door into the sleeping man’s eyes and led him to the conclusion which he would have arrived at if he had been awake, namely that a candle had fallen over and set something alight in the neighbourhood of the body.… the content of the dream must have been overdetermined and … the words spoken by the child must have been made up of words which he had actually spoken in his lifetime and which were connected with important events in the father’s mind.… We may … wonder why it was that a dream occurred at all in such circumstances, when the most rapid possible awakening was called for. And here we shall observe that this dream, too, contained the fulfillment of a wish. The dead child behaved in the dream like a living one: he himself warned his father, came to his bed, and caught him by the arm … For the sake of the fulfillment of this wish the father prolonged his sleep by one moment. The dream was preferred to a waking reflection because it was able to show the child as once more alive. If the father had woken up first and then made the inference that led him to go into the next room, he would, as it were, have shortened his child’s life by that moment of time.” Ibid., 509–510.

“Ten followers of the mystic Islamic Sufi movement were killed last night … According to a US military briefing, the crowd of Sufi worshippers was attacked by a suicide car bomber in the village of Saud, near the town of Balad, about 425 miles north of Baghdad, late last night.… Sufi mystics are a target of Islamic extremists, who dispute their interpretation of the Koran. Twelve people were also injured in the explosion. Ahmed Hamid, a Sufi witness, told the Associated Press: ‘I was among 50 people inside the tekiya (Sufi gathering place) practicing our rites when the building was hit by a big explosion. Then, there was chaos everywhere and human flesh scattered all over the place.’” Sam Knight, Times Online, June 3, 2005, →.

Jacques Derrida: “As for the sacrifice of the son by his father, the son sacrificed by men and finally saved by a God that seemed to have abandoned him or put him to the test, how can we not recognize there the foreshadowing or the analogy of another passion? As a Christian thinker, Kierkegaard ends by reinscribing the secret of Abraham within a space that seems, in its literality at least, to be evangelical” (The Gift of Death, 80–81). Of a philosopher who wrote in the same book that the sacrifice of the son of Abraham “belongs to what one might just dare to call the common treasure, the terrifying secret of the mysteriumtremendum that is a property of all three so-called religions of the Book, the religions of the races of Abraham,” I would have expected, were his inclusion of Islam thought through, that he reread Jesus Christ’s night at the garden of Gethsemane through the detour of the Qur’ânic episode in which a sleeping father dreams that he has to sacrifice his son. “Jesus went with his disciples to a place called Gethsemane, and he said to them, ‘Sit here while I go over there and pray.’ He took Peter and the two sons of Zebedee along with him … Then he said to them, ‘My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death. Stay here and keep watch with me’” (Matthew 26:36–38). When he said, “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death,” which death was Jesus talking about? Was it his state of overwhelming sorrow then? Was it his destined imminent death on the cross? No; what Jesus said in the garden by means of ‘My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death,’ the Son (Christ) understood but the messenger(s) (Peter and the two sons of Zebedee) did not. His foreboding was confirmed when he went a little farther relative to his three disciples and prayed, “My Father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me. Yet not as I will, but as you will” (Matthew 26:39). There was no response from the Father! Christ’s soul was overwhelmed with sorrow to discover that God the Father was then sleeping and dreaming, dead—if in the case of humans, (dreaming) sleep is a sort of “little death,” in the case of God, (dreaming) sleep is death! When Jesus Christ said, “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death,” the death he, “the life” (John 11:25), was speaking about was not, indeed could not be his death, but rather the death of God the Father. While sleeping and dreaming, God the Father could not understand him since in that condition He understands only the dead (in this, He is similar to Daniel Paul Schreber’s God: “Within the Order of the World, God did not really understand the living human being and had no need to understand him, because, according to the Order of the World, He dealt only with corpses” (Memoirs of My Nervous Illness, trans. and ed. Ida Macalpine and Richard A. Hunter (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), 75)). This is one variant of the death of God in Christianity: not the death of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, God as the Son (exemplified pictorially by Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521)), but the death of God the Father, the beloved who paradoxically died notwithstanding His eternity (by sleeping and dreaming), forsook His beloved and lover (Matthew 27:46)! Why did the Father go on dreaming during His Son’s first two exoteric prayers to Him on that night notwithstanding that had He awakened He could possibly have spared His son the crucifixion? Jesus went back and forth twice between two kinds of companions whom he had expected to keep watch with him, his disciples (“Keep watch with me” (Matthew 26:38) and God the Father (“He who watches over you will not slumber; indeed, he who watches over Israel will neither slumber nor sleep” (Psalm 121:3–4); cf. Qur’ân 2:255: “Allâh! There is no deity save Him, the Alive, the Eternal. Neither slumber nor sleep overtaketh Him” (trans. Pickthal)), but that he found sleeping (and dreaming) (“Then he returned to his disciples and found them sleeping. ‘Could you men not keep watch with me for one hour?’ he asked Peter. ‘Watch and pray …’ He went away a second time and prayed, ‘My Father, if it is not possible for this cup to be taken away unless I drink it, may your will be done.’ When he came back, he again found them sleeping …” (Matthew 26:40–43)). The sleep and dream of God is (not a night in the world but) the night of the world; I am therefore not surprised that the disciples felt such an irresistible urge to sleep and dream. Christ does not need to be resurrected since he, the life, cannot die (cf. Qur’ân 4:156: “They said (in boast), ‘We killed Christ Jesus the son of Mary, the Messenger of Allâh’;—but they killed him not, nor crucified him, but so it was made to appear to them”); he is the resurrection (Jesus said to her, “I am the resurrection and the life” (John 11:25)) only in relation to others, including and primarily God the Father. Between leaving his disciples for the third time and praying again (“So he left them and went away once more and prayed the third time, saying the same thing” (Matthew 26:44)), God the Son awakened God the Father by resurrecting Him from the sort of death His sleeping and dreaming is! Jesus Christ’s greatest miracle, his resurrection of God the Father, was not witnessed by his disciples and was not reported in the Gospels. Now, to his third prayer, he received an answer from God the Father; God the Father indicated to him that His will was that he, the Son, be crucified. Then the Son of God “returned to the disciples and said to them, ‘Are you still sleeping and resting? Look, the hour is near, and the Son of Man is betrayed into the hands of sinners. Rise, let us go! Here comes my betrayer!’ While he was still speaking, Judas, one of the Twelve, arrived. With him was a large crowd armed with swords and clubs.… Then the men stepped forward, seized Jesus and arrested him. With that, one of Jesus’ companions reached for his sword, drew it out and struck the servant of the high priest, cutting off his ear. ‘Put your sword back in its place,’ Jesus said to him, ‘… Do you think I cannot call on my Father, and he will at once put at my disposal more than twelve legions of angels? But how then would the Scriptures be fulfilled that say it must happen in this way?’” (Matthew 26:45–54). It seems that God fell asleep and dreamt again, with the consequence that “about the ninth hour Jesus cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?’—which means, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’” (Matthew 27:46). And it seems that crucified Jesus Christ had again to resurrect God—while he was being mocked and challenged: “The chief priests, the teachers of the law and the elders mocked him. ‘He saved others,’ they said, ‘but he can’t save himself! … Let him come down now from the cross, and we will believe in him.’ … In the same way the robbers who were crucified with him also heaped insults on him” (Matthew 27:41–44).

Jacques Derrida, The Gift of Death, 64.