On December 9, 2010, I was “kettled,” or contained against my will, for over eight hours in London’s Parliament Square in freezing conditions, without food, drink, or toilets. I was not alone. Along with thousands of others—including students, lecturers, trade unionists, and schoolchildren—I was on the streets that day to protest against the UK government’s swingeing plans to cut funding and raise fees in English universities. The plans have been rightly, and widely, criticized as an attack on the very idea of a university education, and on its value as a public good.1 By tripling student fees and making substantial reductions to state-funded university teaching—including a 100% cut to arts, humanities, and social science subjects—the government is hoping to decisively switch the burden of university funding from the public purse to the pockets of individual student-customers. This is the latest move by disaster capitalists in the UK government intent on using the banking crisis, and resulting government debts, as an excuse to force through a radical neoliberal agenda to roll back the state further even than what Margaret Thatcher could have dreamed possible in the 1980s.

But, lest we forget, my experience of being kettled was a rude reminder that this shrinking of the state should not be confused with a waning or disappearance of state power. On the contrary, and as Peter Hallward has pointed out, it is precisely in contexts such as these that neoliberalism needs state power in order to brutally enforce unpopular changes to social democratic institutions.2 The costs of such changes are, of course, going to be calculable in the future, for example, in forthcoming dramatic increases to levels of student debt, in university jobs likely to be lost over the next few years, or in the soon-to-be accelerated marketization of the university experience. But the political costs of such neoliberal measures are also evident now in terms of the broad diminution of democracy itself, a diminution dramatized in the curtailment of the right to protest on that December 9, and the media reporting of it.

Things had begun peacefully enough that day. Along with a handful of lecturer friends, I had marched as part of an organized demonstration through the streets of central London to St. James’s Park. After stopping off for a bite to eat at the cafe in the park, we then made our way via Parliament Square in order to take part in the second leg of the day’s activities—a rally and vigil organized by the National Union of Students and the University and College lecturers’ Union. Once in the Square, however, it became clear that we were to be prevented from passing through it by the Metropolitan Police, and therefore prevented from completing our day of marching and protesting as planned. At just after 3pm, police in riot gear, some on horseback, moved in to close off all exits from the square, effectively encircling and summarily incarcerating thousands of peaceful protestors within it. There was to be no escape for the next eight hours. Once contained, or “kettled,” we were then subjected to a sustained campaign of violence, intimidation, and deliberate misinformation.

Throughout the afternoon, the crowd of protestors suffered unannounced and sudden charges by baton-wielding mounted police. The collateral damage of such actions should be obvious and has been well reported in the press, including twenty-year-old student Alfie Meadows who underwent three-hour emergency brain surgery after being struck by a police baton, and Jody McIntyre, who lives with cerebral palsy, who was twice pulled from his wheelchair and dragged across the tarmac by police officers.3 Personally, I saw a number of protestors with bloodied faces and head wounds, evidencing in sickeningly habitual manner the violent operation of the repressive state apparatus. Of course, the view issuing from the Metropolitan Police, and much of the British mainstream media, is that police were only responding to levels of protestor violence within the kettle. All I can say is that, from my perspective at least, the violent action and criminal damage caused by protestors ensued after the kettling had begun. To my mind it was inflamed, if not indeed caused, by the kettle itself.

The police repeatedly told protestors that they were free to leave the square by such-and-such an exit but it became clear that, after going to the various “exit” routes indicated by police, nobody was really being allowed to leave. I can only surmise that sending protestors on such wild goose chases was actively designed to make people feel helpless and “boil” their anger and frustration until it overflowed into acts of criminal damage. And once protestors did start attacking government buildings on the square, police initially stood back and allowed it to happen, presumably with a view to discrediting the protests through the resulting sensational images offered up to a hungry and attendant media. Interestingly, even though the police weren’t there, for example, to stop angry demonstrators smashing up the Treasury, the media were there. A determined group of cameramen jostled for position, and stayed close to masked youths as they tried to force their way in to government buildings. Each crash of a rock against, or jabbing of a pole through, the Treasury’s bomb-proof windows was lit-up by bursts of photographic flash-guns, as if helpfully held aloft so that the violent few could see what they were doing (it was dark by this point). This production of a temporary, and effectively lawless zone, in which protestors are given enough rope to metaphorically hang themselves in the eyes of a presumptively outraged media public, can be seen as a continuation of a strategy used in an earlier student protest. On November 24, 2010, a police van was suspiciously left at the heart of another student kettle, judiciously positioned by the police to be vandalized by protestors. The image of the van then dutifully played its part in disapproving media reporting of the protests the following day.

So the incitement to violence, and the media capture of that violence, can be seen as crucial to the success of kettling as a politicized strategy of policing. This puts the media—or at least the corporate media—firmly in kettling’s orbit. Further still, the media could be viewed as one component part of a wider strategy of containment, a technology of information management if you will, which is co-extensive with the kettling operation itself. Seen in this quasi-Foucauldian way, the media extends the containment virtually through the wider dissemination of police misinformation, “kettling” its viewers and listeners by keeping them in the dark about what is actually going on. For instance, throughout the afternoon BBC News reported the police line that protestors were allowed to leave, and were not being held against their will in the square. This, as I have already indicated, was not true. Similarly, later on in the evening, after the kettling of over one thousand protestors for an hour and half on Westminster Bridge, Ben Brown on BBC News 24 reported that police routinely made announcements to those held, calling for patience and informing us that we would soon be allowed to disperse. This was a blatant lie. I was there. Not one announcement was made of any kind. Nobody knew why we were being held or for how long. Similarly, the viewers of BBC News 24 were to be no wiser, even after the event, as Brown’s reporting extended the police’s campaign of misinformation.

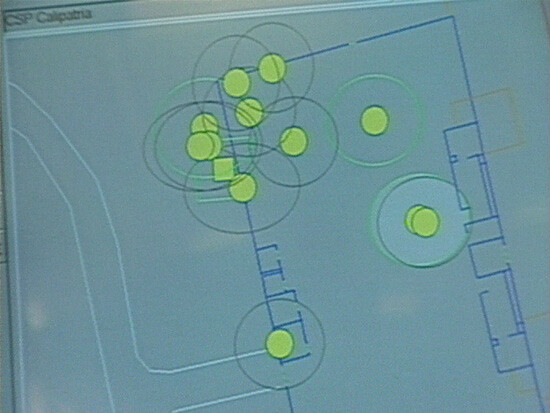

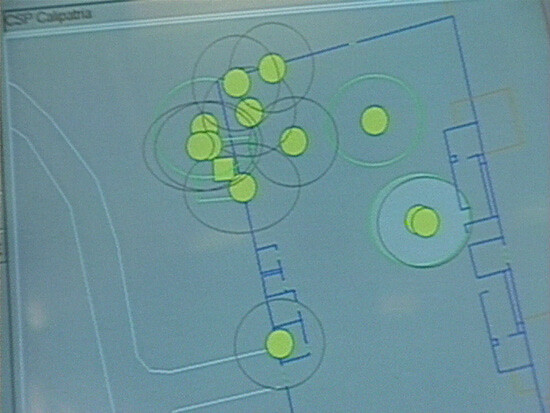

I finally left the kettle that evening shortly after 11:00 p.m. Each of us were allowed to leave one-by-one and forced to do a “walk of shame,” as one of my perceptive students so aptly described it. We had to walk single file down a long line of riot police, remove any headgear (or have it ripped from our heads), and finally pass before a police camera in the full glare of its lights and winking red operation button. There was no equivocation. We were being treated as criminals, our appearance captured on video to be played back against hours of police footage, and processed through face-recognition software.

Whereas I left feeling numb, I woke up the following day boiling with rage. Perhaps I had suppressed my anger the previous day. Had I not, perhaps I too would have been thrusting a pole through the Treasury windows? Much has been made about the politically mobilizing power of anger, but this didn’t feel so mobilizing—at least not in the first instance. It somehow felt more insidious and invasive: as if the anger was not mine, that it had been imposed upon me somehow by the organs of the British State—parliament, police, media—acting in authoritarian concert that day. I felt as if I’d been impregnated with rage, goaded into feeling it by the unjust punishment I received for exercising my democratic right to protest.

Looking back on the Parliament Square incident a couple of weeks later, it still looks like a bad day for democracy: along with thousands of other protestors I had my right to protest curtailed, a number of peaceful protestors were injured by police, the media systematically misrepresented the events of the day and morally disparaged the protestors, and, to cap it all, the first step towards disastrous and long-lasting changes to English universities got voted through the House of Commons. For this latter measure, there was, and still is, no democratic mandate. The Liberal Democrats, one of the parties making up the current coalition government, actively campaigned against any rise in tuition fees at the last general election. Which means they were voted in to actively resist the measures that they, and their government, now drive forcibly through Parliament.

All of this only adds to my anger. But even though my anger hasn’t subsided since being kettled, it does feel somewhat different now. It no longer feels like something engineered in me from without. Instead, it feels like an emotion I’ve felt before, when, as a student I faced police horses charging on a demonstration against what was then the Thatcher government’s plans for higher education. Which is to say it feels, uncannily, like the 1980s all over again. Other middle-aged activists I’ve spoken to in recent months have, perhaps unsurprisingly, expressed a strikingly similar sense of what the contemporary political situation feels like. This is the reason why I’ve spent much of this article writing about emotion. For if it feels like that, and feels that way to many, then perhaps it is like that. The values of social democracy are under deliberate attack again by a bold and ideologically determined cadre at the heart of government, no matter the spin about its “progressive” measures. It is right to be angry again.