Perhaps you or someone you know does not have enough money. And perhaps you or they are artists, since most artists typically do not have enough money—especially in the United States, where art is always the last thing to be funded. And artists are generally so dedicated to art that they ignore profit.

But artists are cultural leaders, and for this reason they can become financial leaders, because money is primarily a cultural product. Money often takes the form of official-looking pieces of paper designed by artists, but furthermore, the credibility of any money rests on cultural messages that validate the institutions claiming power over commerce. And much of our society relies on the cultural messages transmitted through official-looking pieces of paper, from mortgages to graduation diplomas. The graphic, written, and musical arts reinforce the belief that financial institutions are authorized to issue and to control money.

Just as artists are essential to the movement of armies, which gather around music, uniforms, flags, so does the artist have a pivotal role in determining the future of money, and the future of the economy. So why shouldn’t artists create their own money? It will not be Monopoly money, but anti-monopoly money. It will be real money to the extent that people trade with it. Community currency does not necessarily replace national currency, but the lack of national currency in places where it does not reach. Even at times when a lot of money is circulating, it is not necessarily being distributed well.

All national currencies, I believe, are funny money. Regardless of whether the value of a currency is higher today or lower the next day, all national currencies are in debt to nature, because all human economies are extracting resources from nature faster than they can be renewed. This is the ecological significance of local economies: you cannot have an economy unless you have a planet with trees and water, with soil for growing food. Business relies on the environment. For this reason, real money is money that renews nature.

In the US, money has become especially worthless because it is no longer backed by gold, but by less than nothing—by rusting industry and trillions of dollars of national debt. During the past 50 years, the primary guarantor of the dollar has been the US military, now based in 150 nations and losing its grip on cheap oil, cheap minerals, and cheap labor. Even the euro depends on natural gas imported from Russia to maintain its vitality. In the next decade one might invest in rubles to make a profit, however, when Russia’s gas, minerals, and forests are eventually exhausted, the only credible money will be that which begins to repair centuries of damage.

Today, even when the official economy is doing well, millions of people are unemployed, millions work jobs they hate, species are eradicated, and the planet’s generous resources are destroyed. While many prefer to work to create beautiful goods or grow beautiful food, to share with others, most official jobs still contribute to corporate domination. The only real money is therefore money that rebuilds communities, rebuilds nature, and rebuilds the future.

These are main reasons why, twenty years ago, I designed paper money for Ithaca, New York. I sensed that the community had done many good things, but needed a way to bind these good things together. During the recession in the early 1990s, my friends and I needed more money—more control over money and what it does. We needed more control of investment, and we wanted to depend less on the American empire. We wanted to strengthen local small businesses. We wanted to reduce interest rates. We wanted to meet more local needs and contribute to a sense of community.

And we wanted to bring humanity to the marketplace. The global marketplace trades numbers at the speed of light, without regard for the damage done to communities or nature. Every big company will say they care about nature, but the imperative is always to make the maximum profit. By contrast, the local marketplace is a real place where people become friends, lovers, and political allies. Through local trade, we become surrounded by people we trust. That has economic and social value, as well a health value.

Whether you seek to be a famous artist or something else, you exist within an economy and you occupy a planet. You need economies that replenish the planet rather than destroy it. And the younger you are, the more urgent it should become that the planet be more bountiful, rather than less. Local currencies have this capability, and in fact they strengthen national currencies. Just as the large lobes of our lungs are healthy when the millions of tiny air sacs they consist of (known as alveoli) are happy, so do tiny neighborhood economies and village economies—which are strengthened by local currencies—actually contribute to the strength and vitality of national economies and their currencies.

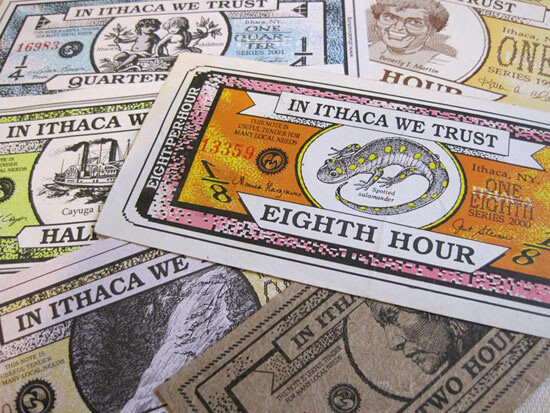

As an artist, it was easy for me to design money—colorful money, with pictures of local children, waterfalls, trolley cars, lizards, and an insect found only near Ithaca. We honor this bug, because such tiny things convert fallen trees into soil, which creates food, which we eat. I called the money HOURS, because it would be backed by labor time rather than property, gold, or law. One HOUR equals $10, or one hour of basic labor. We all have time, and—without gold or silver, which the dollar does not have either—we created money backed by our time. It is flexible—if a professional needs $100 an hour, he or she can charge 10 Ithaca HOURS per hour.

The next task was to find people who would use it. So I began waving around to friends, saying, “This is going to be money; we’ll trade it with each other; sign up here,” and handed them my clipboard. To their credit, they didn’t say it was dumb idea. They didn’t say I would get them all in trouble. They said, “OK, let’s try this.”

To then to expand the system, I began to create a culture of affection around this money and its use. I spoke with thousands of people and hundreds of businesses over the first eight years of Ithaca HOURS, convincing them to join. I published a newspaper directory six times a year to promote the system. Over the next few years, thousands of individuals and five hundred businesses traded HOURS—a bank, a hospital, the transit system, movie theatres, the public library, the bowling alley, restaurants. You can buy land and you can pay rent. Food was the largest category. Our directory rivaled the telephone directory. We even created our own local nonprofit health insurance. Grants of HOURS have been made to over a hundred community organizations. Loans of HOURS worth tens of thousands of dollars have been made without interest charges. Millions of dollars worth of this money have been transacted over the last twenty years.

This system began three years before email, and I soon began to collect email addresses, which made it easier to communicate with people. I created a list of eight thousand residents to keep us up to date on the latest developments. Yet, although I set the table, it was the people who brought the feast. They explained the money to each other, and there were tens of thousands of conversations about why this money was good and why it was important to control money. We call our money HOURS rather than dollars or euros or any other national name, since we are all fellow workers and fellow citizens.

This was a vastly cultural and artistic process relying extensively on graphic arts, symbols, and cartoons. My newspaper, HOUR Town, published three hundred success stories featuring our local currency. I asked people how they earned Ithaca HOURS, how they spent Ithaca HOURS, and why they liked them, and their answers emphasized four benefits: they gained extra income, they wanted to be less dependent on the empire, they wanted to clean the environment, and they wanted to enrich their community.

After spending eight extremely enjoyable years working hard as full-time HOUR networker, I transferred the HOUR system entirely to its elected board of directors so that I could develop a health cooperative I had started—the Ithaca Health Alliance. The Ithaca HOURS board of directors has been dedicated and intelligent, and did some things better than I did, but they did not find another person to promote the system by walking the streets, and the system is now smaller as a result. Across the United States, about eighty other HOUR monies began based on Ithaca’s, and most of them have faded away for the same reason. Initiated by enthusiastic friends or neighbors wanting to create a community institution much like a food co-op or credit union, they did not realize how labor-intensive their currency system would become. For this reason, I suggest the following Recipe for Successful Local Currency, with six ingredients:

1. Hire a networker. Ithaca’s HOURS became huge because, as I said, during their first eight years they could rely on a full-time networker to constantly promote, facilitate, and troubleshoot circulation. This meant lots of talking and listening. Just as national currencies have armies of brokers who help the money to move, local currencies need at least one paid networker. You can offset the need to pay the networker with national currency by finding someone to donate housing, then find others to donate harvest, health care, entertainment, and so forth.

2. Design credible money. Make it look both majestic and cheerful to reflect your community’s spirit. Feature the most widely-respected symbols of nature, buildings, and people. Use as many colors as you can afford, and then add an anti-counterfeit device. Ithaca has used local handmade paper made of local weed fiber, but recently settled on 50/50 hemp/cotton. Design the notes professionally—cash is an emblem of community pride.

3. Be everywhere. Prepare for everyone in the region to understand and embrace this money so that it can purchase everything, whether listed in the directory or not. This means broadcasting an email newsletter, publishing a newspaper at least quarterly, sending press releases, blogging, cartooning, gathering testimonials, writing songs, hosting events and contests, managing a booth at festivals, and perhaps producing a cable or radio show. Do what you enjoy, do what you can. Imagine millions of dollars worth of this currency circulating to stimulate new enterprise, as dollars fade away in the meantime.

4. Be easy to use. Local money should be at least as easy to use as national money, not harder. No punitive “demurrage” stamps—inflation is demurrage enough. No expiration dates—instead, inspire spending by emphasizing the benefits of keeping the money moving to each and to all. Hungry people want food, not paper, so hard times can speed circulation. Get ready to issue interest-free loans. The interest you earn is community interest—your greater capability to hire and help one another. Start with small loans to reliable businesses and individuals. Give grants to groups.

5. Be honest and open. All records of currency disbursement are displayed upon request. Limit the quantity issued for administration (office, staff, and so forth) to 5% of total to restrain inflation. We make this very clear so that people do not think that we are creating some kind of a racket or trick—to emphasize that the currency is for the community, not for us. We are building a service.

6. Be proudly political. Local folks from all political backgrounds find common ground using local cash. But local money is a great way to introduce new people to the benefits of green economics and solidarity. I enjoyed arguing with local conservatives, then agreeing on the power we both gain by trading our money. Hey, we’re creating jobs without clearcutting, prisons, taxes, and war! You can make it more likely that your money is spent for grassroots eco-development by publishing articles that reinforce these values.

When you control money, you not only meet more local needs, create more jobs, and develop a friendlier local economy. You will have created a powerful tool with which to rebuild civilization. I have always intended for Ithaca HOURS and other currencies to lead to vast change. That’s because I’m from America, which is falling apart. I have long believed that American cities need to be entirely rebuilt to be in harmony with nature, so that we do not need fossil fuels to keep our homes warm and to cool them. It’s so ridiculous that we have built a civilization that depends on destroying the planet to keep ourselves alive today.

The formal economy often confines broader human aspirations. Some people are quite satisfied, and simply want lots of money and a comfortable part in the existing system. Artists, on the other hand, define the world. Most commerce depends on artists to brand and market goods. Buildings are designed with artistic intentions, for better or worse. And every artist must decide which future he or she will serve.

Whether you consider yourself an artist or not, anyone can start their own money system, backed by their own networks of trust. Any city has hundreds of significant networks of trust, whether professional, religious, hobby-based, neighborhood, and so forth. Bring them together to trade, on any scale, and you have started a revolution. These networks can become the basis of regional, national, and global money that respects labor, respects this planet, and respects the arts.