There is no possibility of escape …

—Graciela Carnevale, “Project for the Experimental Art Series” (1968)

Let me go, I’m an artist.

—Protestor being arrested during a 1968 demonstration at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires1

As I noted in the first part of this essay, revolutionary action in the Leninist tradition must be guided by an overarching political strategy (the “science” of socialism) devised by alienated members of the bourgeois intelligentsia, and subsequently “communicated … to the more intellectually developed proletarians.” For Voline, action is defined as the straightforward liberation of the redemptive energies of the working class. Debray brings us a third model of agency. For Debray, action is purely instrumental, determined only by military necessity, but nevertheless capable of inspiring fervid devotion and self-sacrifice among peasants and the urban working class. He relies here on the tradition of the revolutionary atentát (attack or assassination), an act of exemplary violence directed at the representatives of an authoritarian regime, and intended to embolden a larger uprising. Debray, like Lenin, fears the spontaneous energies of the working classes and insists on their necessary guidance by foquista cadres, who will help them grasp the nature of their own oppression and determine the steps necessary to overcome it.

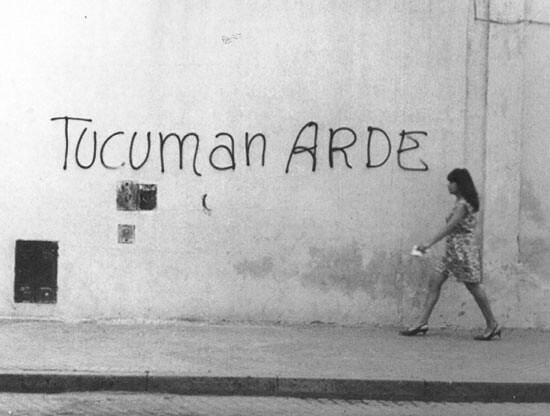

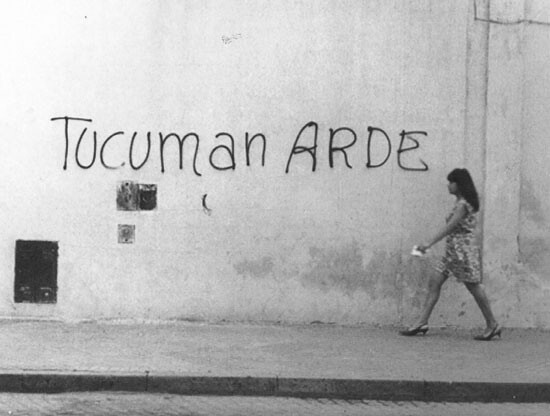

It was, of course, not uncommon for Latin American artists to embrace revolutionary political rhetoric in the 1960s. In their famous Assault Text, delivered to the Argentine museum director Romero Brest in August 1968, Juan Pablo Renzi, Norberto Puzzolo, and Rodolfo Elizalde declare

that the life of “Che” Guevara and the actions of the French students are greater works of art than most of the rubbish hanging in the thousands of museums throughout the world. We hope to transform each piece of reality into an artistic object that will penetrate the world’s consciousness, revealing the intimate contradictions of this society of classes.”2

Graciela Carnevale also sought to “penetrate the consciousness” and “reveal the contradictions” of class society. In this task she found it necessary to adopt the foquista’s callous disregard for pain and suffering. In her case, the violence of guerrilla warfare is directed not against the military forces of the Onganía dictatorship, but against its potential victims: the students, artists, and intellectuals attending the Ciclo de Arte Experimental in Rosario. This doubling or reiteration of aggression was necessary in order to force her audience members out of their “passivity” and to “provoke [them] into an awareness of the power with which violence is enacted in everyday life.” According to Carnevale,

[t]he reality of the daily violence in which we are immersed obliges me to be aggressive, to also exercise a degree of violence—just enough to be effective—in the work. To that end, I also had to do violence myself. I wanted each audience member to have the experience of being locked in, of discomfort, anxiety, and ultimately the sensations of asphyxiation and oppression that go with any act of unexpected violence.3

As Carnevale suggests, only the artist can grasp the interconnected totality of violence within modern society,

from the most subtle and degrading mental coercion from the information media and their false reporting, to the most outrageous and scandalous violence exercised over the life of a student.4

Rather than needlessly exacerbating the anxiety of viewers already on the edge after weeks of police brutality, Carnevale’s action can be seen as therapeutic in nature. She will administer a kind of homeopathic remedy, in which the patient is treated with the diluted version of a substance that would otherwise cause illness. Hence, the “discomfort” created by physical confinement in the gallery will produce a heightened awareness of the far more damaging repression imposed by the Onganía regime. However, as I’ve already noted, this event occurred after protests among the intelligentsia of Buenos Aires— most recently the occupation of the University of Buenos Aires—had been cruelly suppressed. If Argentines were “passive” it wasn’t due to a lack of awareness on their part, but rather to an all-too-immediate recognition of the violent consequences that would result from any act of resistance.

While Carnevale sought to precipitate some sort of cathartic response from the audience, they were reluctant to break the glass and free themselves (although some did attempt to remove the door hinges). It’s impossible to accurately reconstruct their responses over four decades later. However, it’s conceivable that their reluctance was due less to their failure to grasp the “reality of daily violence” than to the fact that they knew they were part of an art project, and were hesitant to damage the gallery and risk injuring themselves by shattering a plate glass window. At least some of them were willing to let the performance run its course and await the artist’s return. In this case, the audience’s reaction may tell us more about the perceived sanctity of the gallery space or norms of authorial sovereignty than it does about the political environment in Argentina at the time. The passerby who eventually freed them, on the other hand, may have simply assumed the gallery-goers were in genuine danger and acted accordingly.

Acción del Encierro reveals some of the symptomatic linkages that existed avant-garde art practice and vanguard political movements during the late 1960s, especially as they relate to questions of agency, resistance, and participation. Foquista action was Janus-faced. On the one hand, foquistas sought to inspire and radicalize the working class and peasants through their own exemplary discipline and self-sacrifice; and on the other, they ruthlessly attacked the military forces of the ruling class. Carnevale collapses these two modes of foquista action: the inspirational and the instrumental, the pedagogical and the martial. In the figure of Carnevale’s gallery-goer, poised between passivity and freedom, awaiting the artist’s intervention to raise and direct their consciousness of oppression, we discover a parallel to the foquista’s struggle to rouse the masses from their torpor and “imbue” them with revolutionary fervor. At the same time, as I noted in the first part of this essay, Carnevale displaces the guerrilla’s characteristic aggression onto her audience, who become surrogates for the absent agents of repression. This punishing and cathartic attack is directed not at the military and political elites who led the junta, but at those Argentines who have been insufficiently vigorous in their efforts to challenge it. Carnevale herself becomes the foquista militant, declaring war on the consciousness of the incarcerated viewer.

The anxiety, discomfort, and fear evoked in Carnevale’s “actors” are the necessary concomitants of advanced art and political enlightenment—or rather, the goals of each are blurred. Carnevale offers a coercive model of participatory art, in which “the spectators have no choice; they are obliged, violently, to participate.”5 Encierro thus functions as a kind of behavioral experiment in which there are only two possible outcomes. Either the participants do nothing, thus confirming their passivity and complicity with power, or they break free and demonstrate their capacity for revolutionary action. In each case the artist retains her position of transcendence, while the viewers are interpellated as corporeal bodies, trapped or sequestered, placed under inexplicable constraints, and then set “free” to act and be judged. This reduction of agency to a simple act of physical resistance or accommodation (representing the liberation or containment of the participant’s “natural impulses”) is emblematic. Carnevale’s work fails to engage the differentiated subjectivities of those people she chooses to confine. They function instead as representatives of a generic political consciousness, symbolizing the Argentine people as a whole in their opposition to, or complicity with, Onganía’s dictatorship.

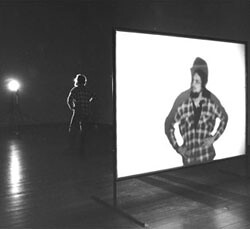

Carnevale’s work exhibits the essentially propositional nature of much Conceptual art. In particular, conceptualism marks a shift from previous concerns with the generative nature of process or physical production (as in Abstract Expressionism, for example) toward a notion of art as the presentation or framing of an assertion (about the viewer, the nature of art, or society). The locus of creative agency lies in the construction of a spatial or formal system into which the viewer is introduced and allowed a limited range of action, predetermined by the artist. Typically, the gallery space undergoes some physical modification—the strategic removal of a wall, the locking of a door, the installation of video surveillance equipment—with the intention of revealing hidden complicities to the viewer (the economic transactions that anchor the ostensibly disinterested display of art, the panoptic nature of modern society, and so forth).6 Whether actual viewers ever experience these insights is of secondary importance. It’s necessary simply to create a space, an apparatus, within which such insights might possibly be induced. The aesthetic quality of semblance or virtuality is thus preserved through the hypothetical nature of a conceptual practice in which propositions remain untested and largely rhetorical. As Sol Lewitt famously declared, “When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair.”7 We might say, as well, that the reception of the work by discrete viewers is equally perfunctory from the artist’s perspective. While Carnevale’s Acción del Encierro involves a relatively reductive understanding of the viewer’s agency, it does at least allow for some verification of her working hypothesis. Even if the viewer does nothing at all in response to the work, they nonetheless confirm the artist’s a priori assumptions about human nature (inaction is equivalent to passivity in the face of political repression).

While Carnevale’s work shares certain generic features with a broader range of Conceptualist practices, it is also informed by the specific conditions of Latin American art during the 1960s and 70s. In particular, her direct engagement with the authoritarian Onganía regime was in marked contrast to the more detached, quasi-philosophical concerns often encountered in Conceptual art in the United States and Europe. American Conceptualists such as Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, and Lawrence Weiner were preoccupied with relatively abstract epistemological questions (e.g., the semiotic contingency of aesthetic or linguistic meaning).8 As historian Mari Carmen Ramirez notes, the “criticality” of Euro-American conceptualism was most often produced through forms of self-reflexivity focused on the discursive and institutional construction of art. In much Latin American conceptual work, this criticality was directed at the political and social structures of authoritarian regimes and the mechanisms of neo-colonial domination. Ramirez states, “the fundamental propositions of Conceptual art became elements of a strategy for exposing the limits of art and life under conditions of marginalization and, in some cases, repression.”9 Writing in 1970, Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles identifies a transition from “art” to “culture” in Latin America:

If Marcel Duchamp intervened at the level of Art … what is done today, on the contrary, tends to be closer to Culture than to Art, and that is necessarily a political interference. That is to say, if aesthetics grounds Art, politics grounds Culture.10

This shift from art to culture is often figured as a loss or abandonment, as art surrenders its privileged immanence to the brutal instrumentality of vanguard politics. “Unlike the political vanguard,” Romero Brest writes in 1967, the artistic avant-garde “does not have an aim to achieve.”11 More recently, critic Jaime Vindel, in his essay “Tretyakov in Argentina,” warns that Argentine artists during the 1960s “took the risk of abandoning the dissensual specificity of their ‘ways of doing’ in order to merge into a continuum that would end up subordinating their activities to the teleology of revolutionary politics.” The implicit valorization of “dissensus” (with respect to what? to what end?) is symptomatic. In making this point Vindel draws on Susan Buck-Morss’s analysis of the tensions between avant-garde art and vanguard politics in revolutionary Russia. Buck-Morss observes:

In acquiescing to the vanguard’s cosmological conception of revolutionary time, the avant-garde abandoned the lived temporality of interruption, estrangement, arrest—that is, they abandoned the phenomenological experience of avant-garde practice.12

However, as we’ve already seen, the questions of agency and instrumentality that are raised at the intersection of the aesthetic and the political cannot be so easily resolved into a simple opposition between autonomy and subordination, spontaneity and premeditation. Certainly, avant-garde art carries its own not-so-secret teleological desires (the reformation of society through the incremental transformation of individual subjectivities), which are evident in Carenvale’s mechanistic picture of human agency and resistance.

Interruption and estrangement may well arise from the viewer’s experience of simultaneity, but they are no less goal-driven in their orientation. Within the singular phenomenological matrix of the avant-garde, who, precisely, is having their consciouness interrupted? And who claims the right to preside over this interruption? For both the foquista and the artist, the viewer, the peasant, or the laborer arrives unformed and in need of renewal or conversion (whether through inspiration or provocation). Each assumes a proprietary or custodial relationship to the consciousness of the Other. Buck-Morss’s defense of lived temporality over the heedless indifference of teleological thinking to the here-and-now is well taken. However, lived temporality unfolds in many ways outside those defined in terms of interruption, estrangement, and arrest. And the relationship between artist and viewer can be produced through many different forms of interaction and engagement, aside from a supervisory provocation.

Agonism and Antagonism

Interpellated as equals in their capacity as consumers, ever more numerous groups are impelled to reject the real inequalities which continue to exist. This “democratic consumer culture” has undoubtedly stimulated the emergence of new struggles which have played an important part in the rejection of old forms of subordination …

—Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (2001)13

As I’ve suggested, the synchronicity between the artist and the revolutionary, between aesthetic and political protocols, is a central feature of cultural modernity. It entails, however, a significant set of displacements. The actions of the revolutionary are directed toward two different constituencies and are defined by distinct forms of affect. First, the revolutionary seeks to reveal the “true” nature of domination to the working class via fairly traditional forms of evidentiary or “realist” documentation (e.g., the use of “exposure literature” by the Bolsheviks). Here the revolutionary assumes a conventional pedagogical role relative to the proletariat. At the same time, the revolutionary seeks to provoke and attack the bourgeoisie and the capitalist state, both as an example of properly military discipline (to be emulated by the working class) and in order to solicit a violent reprisal from the institutions of bourgeois power, which will serve to mobilize and cohere the working class in response (or, at the very least, to win the support of sympathetic factions within the bourgeoisie).14 In doing so, the revolutionary potentially increases the suffering of the working class (as they become targets for possible retaliation), but with the goal of securing their ultimate liberation. The revolutionary doesn’t attack the working class directly, but rather hopes to incite the state to do so in order to precipitate a revolutionary “event.” The revolutionary’s violence is reserved for the bourgeoisie, who will first be provoked, and then destroyed.

As Carnevale’s work demonstrates, avant-garde artistic production often collapses these two modes of address: the education and consciousness-raising of the proletariat and the provocation and punishment of the bourgeoisie. The result is a form of artistic practice in which provocation itself is assigned a pedagogical role, and an increasingly generic implied viewer (the bourgeois who refuses to acknowledge the suffering in which he is complicit), whose presumed ignorance is the necessary precondition for this same pedagogical function. Carnevale’s work has gained renewed attention in recent years as part of a more general re-affirmation of aesthetic conventions that define avant-garde art as a form of aggressive disruption intended to increase the viewer’s awareness of his or her own culpability in dominant forms of power. Thus critic Claire Bishop, one of the leading exponents of this tendency, insists on the transformative potential of “awkwardness and discomfort” in the viewer’s experience of contemporary art and praises those artists who are willing to place their subjects in “excruciating” situations characterized by “grueling duration.”15 Rather than promoting a reviled “social harmony,” advanced art, according to Bishop, must promote a cathartic “relational antagonism” capable of “exposing that which is repressed.”16 One of the most well known exemplars of this approach is Spanish artist Santiago Sierra, who presents viewers with various tableaux of exploitation and subordination (workers paid to hold up walls for extended periods, addicts tattooed in exchange for a fix, and so forth). As curator Cuauhtémoc Medina contends, “Sierra’s work is designed to produce constant shock” as he “blows the whistle on the fraud that prevails in the history of emancipation.”17

The writings of philosophers Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe have played an important role in these debates. Bishop cites Mouffe extensively in her influential essay “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” published in the journal October. Laclau and Mouffe first gained attention in the mid-1980s for their attempt to develop what we might think of as a postmodern concept of political resistance. Poststructuralist theory, ranging from Jacques Lacan’s critique of ego psychology to Michel Foucault’s research on the necessary interdependence of resistance and power, did much to discredit existing notions of agency and identity (both collective and individual). However, while poststructuralist theory was quite good at exposing the various forms of complicity that accompany conventional models of volitional action and collective identity, it was less helpful in providing alternatives. Laclau and Mouffe sought to develop a political theory that was consistent with the emerging insights of poststructuralist theory, while also allowing for coherent and effective forms of resistance. Their reconstructive effort began with a critical reappraisal of the Marxist tradition. Laclau and Mouffe hoped to preserve some components of that tradition (in particular, Antonio Gramsci’s concept of “hegemonic” political formations) while discarding the embarrassing Hegelian baggage (for Laclau and Mouffe, the proletariat is just another transcendent subject in need of deconstruction).

In their idiosyncratic merging of Marxism and poststructuralism, Laclau and Mouffe came to view the de-centering of the subject prescribed by continental theory not as a barrier to the development of organized political resistance, but rather as a key moment in the long march toward democratic pluralism.18 Drawing on the work of Lacan, they sought to challenge the primacy of class as a privileged signifier in the Marxist tradition, arguing that all forms of identity must be seen as provisional or contingent. Social or political conflict isn’t, ultimately, the product of historically specific modes of economic domination, but rather, is hard-wired into our epistemological orientation to the world, as we vainly seek to recover a mythic sense of plenitude and ontological wholeness. Unable to accept our fragmented and dependent condition, we insist on seeing others as threats to a fictive subjective integrity. Fortunately, this debilitating and destructive tendency can be corrected. We need only learn to recognize and embrace our intrinsically divided nature or, as Lenin might say, be brought to the proper level of consciousness. This insight, this awakening, will allow us to maintain our capacity for political agency without succumbing to the often violent defensiveness associated with conventional identities based on fixed notions of class, community, nationality, or ethnicity. The goal of revolution is no longer the liberation of a single oppressed class, ethnicity, or gender, but a global reconfiguration of our relationship to difference in all its guises and forms, leading to a society based on a non-instrumentalizing “agonistic pluralism.”

Conflicts between self and other won’t disappear in this brave new world, nor should they. In fact, they are the very stuff of radical democracy, and a constituent of human subjectivity itself. We simply need to acquire a more reflective relationship to conflict (becoming “adversaries” rather than “enemies,” as Mouffe writes). They advocate not the elimination of “conflict” (either through enforced consensus or the random splay of postmodern indeterminacy) but rather, its “taming.”19 A destructive antagonism must be domesticated and turned into a healthy agonism, because otherwise our natural propensity for violence and instrumentalization will lead us inevitably toward fascism. The echoes of Schiller are evident: before we can engage in political action we require a process of transformative, essentially aesthetic, re-education. Thus Laclau and Mouffe argue for a re-tooling of individual human subjectivity in such a way that we can treat antagonists as peers or colleagues rather than as existential threats or potential victims. Mouffe writes:

the aim of democratic institutions is not to establish a rational consensus in the public sphere, but to defuse the potential of hostility that exists in human societies by providing the possibility for antagonism to be transformed into “agonism.” By which I mean that, in democratic societies, while conflict neither can or should be eradicated, nor should it take the form of a struggle between enemies (antagonism), but rather between adversaries (agonism).20

In this suitably ironic form of participatory democracy, we contend over substantive issues and differences while preserving an awareness that all differences are contingent, and any final resolution is impossible. Thus, the adversary is “the opponent with whom we share a common allegiance to the democratic principles of ‘liberty and equality for all’ while disagreeing about their interpretation.”21 But how will people come to accept difference without antagonism? How will they be prepared for agonistic interaction? According to Laclau and Mouffe this transformation will be brought about, in part, through our exposure to the works of philosophers, whose task it is to bring us into a proper consciousness of the world. As Mouffe notes:

Political philosophy has a very important role to play in the emergence of this common sense and in the creation of these new subject positions, for it will shape the “definition of reality” that will provide the form of political experience and serve as a matrix for the construction of a certain kind of subject.22

Perhaps what is most striking about Laclau and Mouffe’s work, aside from their relatively exalted view of the efficacy of academic philosophy, is the readiness with which they transpose a set of hermeneutic procedures derived from poststructuralist theory (primarily, the process of revealing the contingency of those forms of subjectivity or knowledge that we normally experience as natural or given) into a formal political program. If we could only imbue the broader public with the reflective consciousness of a Derrida or a Lacan, a more just and equitable society would inevitably follow. The consciousness of the master theorist becomes the normative model of political enlightenment toward which we should all aspire.

In fact, the recognition that our individual or collective identity is contingent is no guarantee that we won’t still seek to harm other people (as evidenced by the violence associated with football matches in Europe, to pick one of many possible examples). As human beings, we have an impressive capacity to maintain two contradictory beliefs at the same (in this case, the awareness that a given collective sensibility is arbitrary, and the willingness to act out on the basis of this sensibility in an extreme or destructive manner). The epistemological “truth” of a given mode of collective identification is of far less importance to most people than the often intoxicating forms of affect and agency that this identity can sanction. In some cases, we might understand collective identification less as a precondition than as a pretext for these forms of agency. Moreover, what we think of as a paradigmatic bourgeois subjectivity, associated with the erosion of certain fixed hierarchies and allegiances, is defined precisely by the mobilization of our capacity for affective investment and the creative re-invention of the self. As Slavoj Žižek has noted, the fluid and mobilized notion of the self celebrated by Laclau and Mouffe is itself a key constituent of contemporary capitalism:

I think one should at least take note of the fact that the much-praised postmodern “proliferation of new political subjectivities,” the demise of every “essentialist” fixation, the assertion of full contingency, occur against the background of a certain silent renunciation and acceptance: the renunciation of the idea of a global change in the fundamental relations in our society … and, consequently, the acceptance of the liberal democratic capitalist framework which remains the same, the unquestioned background, in all the dynamic proliferation of the multitude of new subjectivities.23

In their attempt to ontologize conflict, to ascribe our capacity for violence to some ingrained resistance to the devastating truth of Lacanian lack, Laclau and Mouffe end up eliding the contingency of resistance itself, its dependence on historically specific formations of power and difference (of which capitalism is one of the most significant in the modern period). Conflict, of whatever kind, becomes a problem to be solved through the acquisition of the proper theoretical insight that, once internalized, will effectively heal the individual and, eventually, society at large. Laclau and Mouffe’s analysis of political resistance thus remains oddly abstract and distant from the exigencies of political practice itself.

In fact, substantive political change during the modern period has routinely involved episodes of violence, physical occupation, armed insurrection, and systemic forms of refusal (e.g., general strikes, riots, sit-ins, passive disobedience, and boycotts). It is precisely through the intersection of conventional political participation (voting, “agonistic” debate and opinion formation in the public sphere, and so forth) and these decidedly “antagonistic” forms of extra-parliamentary action, that real changes in the distribution of wealth, power, and authority have been achieved.24 Thus, the “taming” of conflict advocated by Mouffe on behalf of an agonistic pluralism entails a misleading and incomplete view of societal transformation. In this respect, she presents an antithetical counterpoint to Régis Debray’s vexed impatience with the “vice of excessive deliberation” and his single-minded reliance on armed resistance as the source of political insight. Both neglect the essentially capillary nature of change, the performative interdependence of the physical and the discursive, the collective and the individual, and the essential points of pressure and counter-pressure exerted along this continuum.

Mouffe believes that artists can play an important part in the civilizing mission of “agonistic pluralism.” While they can’t claim to offer anything like a “radical critique,” according to Mouffe, this doesn’t mean that their “political role has ended.” Rather, once they have discarded the “modernist illusion” of their “privileged position,” artists can contribute to the “hegemonic struggle by subverting the dominant hegemony and by contributing to the construction of new subjectivities.”25 In order to create these “new subjectivities,” art will join with political philosophy to produce

counter-hegemonic interventions whose objective is to occupy the public space in order to disrupt the smooth image that corporate capitalism is trying to spread, bringing to the fore its repressive character.26

“Critical artistic” practices, according to Mouffe, “foment dissensus,” seeking to “unveil all that is repressed by the dominant consensus” and make “visible what the dominant consensus tends to obscure and obliterate.”27 What is strangely absent from this veritable orgy of unmasking and disruption is any meaningful account of the actual reception of the initial revelatory gesture. The complex process of representation is reduced to a kind of unmediated, theophanic epiphany.

Mouffe writes as if the “truth” of capitalism were a simple objective fact, as if the only thing preventing emancipation is an adequate knowledge of a clear and singular reality that has been deliberately suppressed.28 Once having received this truth, the viewer will naturally and spontaneously feel compelled to take up revolutionary struggle. But the repressive nature of capitalism is hardly a secret. In fact, what is most telling about many contemporary responses to capitalism (as it launches itself against the remaining vestiges of the public sector in the United States and now Europe) is the almost masochistic enthusiasm with which the “discipline” of the market has been embraced by those most likely to suffer its negative consequences. The success of the Tea Party is a case in point. In the United States, certainly, the Republican party has found it a relatively simple matter to make many working-class people angrier about federal funding for National Public Radio or the pensions of librarians and school teachers, than they are about the unprecedented concentration of wealth among the upper class, massive bailouts for Wall Street banks, or thirty years of increasingly regressive tax policies that have robbed their children of access to a decent education. While the Occupy Wall Street movement offers some hope of developing a counter-narrative capable of challenging the perceived inevitability of neo-liberalism, its long-term efficacy has yet to be determined. Certainly, its focus on the “process” of deliberative democracy (often at the expense of operational efficiency) and its trust in the spontaneous emergence of political insight out of consensual exchange would have been anathema to both Lenin and the Debray of the late 1960s.29

Given Mouffe’s readiness to sacrifice the autonomy of art to the exigencies of “hegemonic struggle,” it is somewhat surprising that Claire Bishop has emerged as one of her most enthusiastic art world adherents (as noted above, Bishop’s “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics” essay is heavily indebted to Laclau and Mouffe’s writing.) Bishop has, in fact, been highly resistant to any challenge to the “privileged position of the artist.”30 Moreover, she has regularly expressed her fear that “aesthetic judgments have been overtaken by ethical criteria” in the evaluation of contemporary art. Her analysis assumes, of course, that ethics and aesthetics constitute entirely separate and distinct modes of critical evaluation and, presumably, domains of experience. Bishop argues that certain critics and curators (myself included) have abandoned all properly aesthetic evaluative criteria and “automatically” perceive all collaborative practices “to be equally important artistic gestures of resistance.” In this view, as Bishop contends “[t]here can be no failed, unsuccessful, unresolved, or boring works of collaborative art because all are equally essential to the task of strengthening the social bond.” She accuses curator Maria Lind of ignoring the “artistic significance” of groups such as the Turkish collective Oda Projesi “in favor of an appraisal of the artist’s relationship to their collaborators.” As a result, Lind’s criticism is “dominated by ethical judgments” as she “downplay[s] what might be interesting in Oda Projesi’s work as art.”31

Bishop has yet to provide her readers with a working definition of art which would allow us to determine what she herself believes is “interesting” about Oda Projesi’s work. This confusion is compounded by her failure, thus far, to offer any detailed case studies of those projects that she identifies with the “ethical turn.” However, I’m less concerned with the logical coherence of Bishop’s claims than with the form that her argument takes, and the underlying set of assumptions on which it depends. These can reveal much about the ongoing continuity of the vanguard / avant-garde dynamic I outline above. While concepts of ethics and aesthetics are clearly central to Bishop’s analysis, she provides no substantive definition of either term. We can extrapolate one possible set of definitions from her critical writing. When she condemns an “ethical turn” in contemporary art practice and criticism Bishop seems to be referring more specifically to the ways in which some artists engage questions of agency and the sovereignty of the artistic personality. Thus, if creative agency itself becomes a point of intervention, reflection, and re-orientation in a given work, if the artist complicates the division between “artist” and “viewer” in some way, or concedes any decision-making power or generative control to participants, their work can be accused of subordinating aesthetics to ethics. There can be no other explanation for artistic practice of this kind than the artist’s simplistic desire to reproduce an “ethical” model of inter-subjective exchange (in the form of naïve “micro-topias” that seek only to “smooth over awkward situations”). This ethical gesture is dangerously utopian because it assumes that it’s possible to eliminate all forms of violence, hierarchy, or difference in social formations. At the same time, it is politically suspect because it implies a corollary belief in the mythic “consensus” of the liberal or Habermasian public sphere, which will inevitably repress or deform the identities of individual participants.

Conversely, artists who treat their subjects in a deliberately objectifying or instrumentalizing manner (e.g., Vanessa Beecroft, Santiago Sierra) are engaging in a legitimately “aesthetic” practice precisely because their work challenges the “community of mythic unity,” disabusing the viewer of the naïve belief that one can ever mitigate violence and objectification in inter-subjective exchange. By amplifying or exaggerating this violence (paying poor people to hold up a wall, endure tattooing or masturbate in the gallery), these “aesthetic” works force viewers to acknowledge their own complicity, their own deplorable capacity for violence, which they would otherwise attempt to repress or deny. The real and symbolic violence enacted by these “aesthetic” artists against their subjects is ultimately intended for their viewers, who will experience a shameful self-recognition in the act of passive witnessing. This shock will be all the more effective because it occurs in a space dedicated to forms of recreational artistic consumption and visual pleasure. Thus, Sierra’s work “disrupt[s] the art audience’s sense of identity,” according to Bishop, and is capable of “exposing how all our interactions are, like public space, riven with social and legal exclusions.”32 Rather than striving to produce a “harmonious reconciliation” or “transcendent human empathy,” Sierra will “sustain tension,” and solicit “awkwardness and discomfort” in viewers.33 These “aesthetic” projects refuse to indulge the viewer’s desire for the false solace of aesthetic transcendence, where they can, for a moment, ignore or forget their inevitable investment in circuits of power, domination and privilege. It is the artist’s job to prevent precisely this act of transcendence and denial by subjecting the viewer to a cathartic, and corrective, shock.

For Bishop, any project that suspends, even temporarily or provisionally, the authority of the artist as the empowered agent who supervises this cognitive disruption becomes ethical and not aesthetic. In the very act of soliciting reciprocal modes of creativity, in breaking down or challenging the adjudicatory distance between the artist and the viewer, the collaborative artist becomes complicit with the entire sordid mechanism of violence, exclusion, and repression on which all collective social forms are based.

The contradictory nature of Bishop’s analysis is evident in this description. While she laments the intrusion of ethics into the domain of the aesthetic, she nevertheless identifies the primary locus of “aesthetic” experience in the strategic production of shame or guilt in the viewer (in order to awaken a presumably dormant ethical sensibility). In an interview from 2009, Bishop praises Santiago Sierra’s projects, such as Workers Facing a Wall (2002) and Workers Facing a Corner (2002), as “very tough pieces” that “produced a difficult knot of affect. If it was guilt, it was a superegoic, liberal guilt produced in relation to being complicit with a position of power that I didn’t want to assume.”34 It’s difficult to understand how any model of artistic production that assigns to the artist the task of eliciting “liberal guilt” in the viewer does not entail an ethical function. In fact, it suggests that the very core of Bishop’s “aesthetic” practice is a form of ethical supervision exercised by the artist over the consciousness of the viewer.35 It is this adjudicatory distance, between the artist and the viewer, that Bishop is most concerned to defend, and which most clearly separates the ethical from the aesthetic, relational kitsch from advanced art, and naïve complicity from subversive criticality in her understanding of art.

Bishop returns us, finally, to Graciela Carnevale, subjecting her audience to “discomfort, anxiety … and the sensation of asphyxiation and oppression” in order to “provoke [them] into an awareness” of the “reality of daily violence.” Over the past century, avant-garde artistic practice has remained remarkably consistent in its understanding of the aesthetic as a zone of punishment and remediation. The consciousness of the viewer, the Other, is a material to be “exposed,” “laid bare,” and made available to the artist’s shaping influence. In his naïve and untutored “spontaneity,” the Other can never achieve full or complete consciousness without the requisite discipline imposed by aesthetic experience (or the leadership of a vanguard intelligentsia). The artist’s sovereignty, on the other hand, is absolute, and the artistic personality itself remains both exemplary and inviolable.

As I’ve argued elsewhere, the collaborative art practices of the past decade and a half suggest that the generation of critical, counter-normative insight can occur outside this conventional, dyadic structure in which the avant-garde artist engenders consciousness in an unenlightened viewer.36 A more thorough exploration of these practices requires us to reconsider many of the underlying assumptions of advanced art itself, especially as these have been informed by a particular understanding of revolutionary theory. In analyzing this work it’s necessary to overcome the tendency to simply project the specific social and institutional determinants of the museum or gallery space onto the widely varying sites, situations, and constituencies that are characteristic of contemporary collaborative and activist art practice. More specifically, it’s necessary to overcome the long-standing tendency to frame critical analysis around the assumed characteristics of a hypothetical bourgeois subject, regardless of the specific class identity or cultural background of actual viewers and participants. It requires as well some ability to distinguish enforced consensus from the forms of shared experience necessary to act both creatively and collectively. In the process, we can develop a more nuanced account of reception and aesthetic experience in contemporary art and, perhaps, in the broader field of political resistance as well.

The protest targeted the awarding of the 1968 Braque Prizes by the French ambassador to Argentina. See Horacio Verbitsky, “Art and Politics,” in Listen, Here, Now! Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, ed. Inés Katzenstein (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2004), 296.

Here is Luis Camnitzer, from a conference presentation in 1969: “The second possibility is to affect cultural structures through social and political ones, applying the same creativity usually used for art. If we analyze the activities of certain guerrilla groups, especially the Tupamaros and some other urban groups, we can see that something like this is already happening. The system of reference is decidedly alien to the traditional art reference systems. However, they are functioning for expressions which, at the same time they contribute to a total structure change, also have a high density of aesthetic content. For the first time the aesthetic message is understandable, as such, without the help of the ‘art context’ given by the museum, the gallery, etc. …” Luis Camnitzer, “Contemporary Colonial Art,” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 229–230.

This and above quotes are from Graciela Carnevale, “Project for the Experimental Art Series,” in Listen, Here, Now! Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, 299.

Ibid., 299.

Ibid., 299.

See, for example, Dan Graham’s Time Delay Room (1974) and Michael Asher’s Untitled installation at Claire Copley Gallery in Los Angeles, also from 1974. Here is one contemporary critic’s response to Asher’s piece: “All that stuff on the walls is gone, along with every bit of privacy. Actually viewers don’t intend social interaction. They come to look at art. But without knowing it, they are an integral part of the work they see. How unsettling, and uncomfortable. There are no visual entertainments to cast intent gazes upon, security in the altered proportions of the room which now seems so long and narrow. Are we in the right gallery? No. Yes. Shall we walk around a little and then saunter out the door, or shall we say the hell with it and stomp on up La Cienega shaking our heads. Oh, of course, the show isn’t up yet. Oh, it is!” Kirsi Peltomäki, “Affect and Spectatorial Agency: Viewing Institutional Critique in the 1970s,” Art Journal 66 (Winter 2007): 37–38.

Sol Lewitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” Artforum 5 (June 1967): 79–83. Republished in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 12.Compare this to Thomas Hirschhorn’s similar formulation in a 2005 interview with Benjamin Buchloh:

Mari Carmen Ramírez, “Blueprint Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America,” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, 554. Ramirez speaks of the effort to recover the “ethical dimension of artistic practice,” paraphrasing Marchán Fiz’s observation that “the distinguishing feature of the Spanish and Argentine forms of Conceptualism was extending the North American critique of the institutions and practices of art to an analysis of social and political issues.” Ibid., 557 and 551.

Mari Carmen Ramírez, “Blueprint Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America,” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, 554. Ramirez speaks of the effort to recover the “ethical dimension of artistic practice,” paraphrasing Marchán Fiz’s observation that “the distinguishing feature of the Spanish and Argentine forms of Conceptualism was extending the North American critique of the institutions and practices of art to an analysis of social and political issues.” Ibid., 557 and 551.

Cildo Meireles, “Insertions in Ideological Circuits,” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, 233. Needless to say, this formulation (aesthetics = art, culture = politics) is problematic and overlooks the necessarily “political” function of aesthetic experience, and of the very distinction between “art” and “culture.”

J. Romero Brest, “Qué es eso de la Vanguardia Artística?” (1967), cited by Jaime Vindel in “Tretyakov in Argentina: Factography and Operativity in the Artistic Avant-Garde and the Political Vanguard of the Sixties,” Transversal (August 2010), multilingual web journal of the European Institute for Progressive Cultural Politics (EIPCP). See →.

Buck-Morss argues, “It is politically important to make this philosophical distinction in regard to avant-garde time and vanguard time, even if the avant-garde artists themselves did not.” Susan Buck-Morss, Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 62, cited by Vindel.

Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (London: Verso, 2001), 164.

This was the case during the student protests in France in May 1968, when the sons and daughters of the middle class were subjected to the kind of violence that had been visited on Algerian immigrants and the working class for many years, occasioning an outraged response. A parallel dynamic was at work in the decision to involve high school students in the marches on Selma in 1965. Images of attacks by Alabama state troopers on peaceful young marchers were widely circulated in the national media and led to widespread condemnation of Alabama’s state government, and by extension, the institutions of Jim Crow segregation. These reactions played a key role in providing broad national support for the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. See Robert Mann, The Walls of Jericho: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Russell, and the Struggle for Civil Rights (New York: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1996).

Claire Bishop, “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents,” Artforum (February 2006): 181. With Bishop, the avant-garde commitment to “difficult” or hermeneutically resistant art (previously articulated via a discourse of abstraction) is transformed into a commitment to work that is “difficult” by virtue of it’s exposure of the viewer’s economic or social privilege as a participant of the art world.

Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Fall 2004): 79. It should be noted here that in this essay Bishop fails to account for the evolution of Laclau and Mouffe’s thought since the mid-80s. In particular, she ignores the key distinction Mouffe introduces between “agonism” and “antagonism” beginning in the late 1990s. As I will suggest, this distinction has significant implications for Bishop’s analysis.

Cuauhtémoc Medina, “Aduana/Customs,” in Santiago Sierra, catalog of the Spanish Pavilion, Venice Biennial 2003, curated by Rosa Martinez (Madrid: Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Dirección General de Relaciones Culturales y Científicas/Turner, 2003), 233 and 17.

Benjamin Bertram notes, “For Laclau and Mouffe, the de-centering of the subject is a key moment in the great modern expansion of pluralism. The death of ‘Man’ (which accompanies the death of the centered subject), however, does not entail the end of humanist values. In fact, Laclau and Mouffe want to envision a ‘real humanism’ (i.e., a historicized humanism).” Benjamin Bertram, “New Reflections on the ‘Revolutionary’ Politics of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe,” boundary 2 22 (Autumn 1995): 86.

Mouffe writes, “According to my conception of ‘adversary,’ and contrary to the liberal view, the presence of antagonism is not eliminated but ‘tamed.’” Chantal Mouffe, “For an Agonistic Public Sphere,” in Democracy Unrealized: Documenta 1 Platform, ed. Okwui Enwezor et al. (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2002), 91. In their strenuous efforts to differentiate themselves from Habermas, Laclau and Mouffe often rely on a caricatured portrayal of an ostensibly hegemonic “consensual” model of democracy, against which their own approach can be seen as constituting a radical critique. In practice, however, the difference between “agonistic” democracy and the free exchange of contending opinions in a Habermasian public sphere is minimal. Habermas certainly never claims that the result of debate in the public sphere is a binding and universal consensus, or that political agents can’t retain a reflective understanding of the contingent basis of political identity itself. As John Brady notes, “There are, I think, very few people who would claim that contestation and agonistic political relations are not part and parcel of politics, do not belong to the very fabric of political practice. Habermas certainly has never denied this.” John S. Brady, “No Contest? Assessing the Agonistic Critiques of Jürgen Habermas’s Theory of the Public Sphere,” Philosophy and Social Criticism 30 (2004): 348.

Mouffe, “For an Agonistic Public Sphere,” 90.

Ibid. It’s unclear how the “common allegiance to … democratic principles” advocated by Laclau and Mouffe does not also imply some form of “consensual” agreement.

Chantal Mouffe, The Return of the Political (London: Verso, 2005), 19.

Slavoj Žižek, “Holding the Place,” in Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left, ed. Judith Butler, Ernesto Laclau, and Slavoj Žižek (London: Verso, 2000), 321.

As noted above, the Civil Rights movement in the American South involved both “agonistic” political action as well as forms of nonviolent protest and violent confrontation (from the Selma marches and Freedom Riders to the use of 23,000 federal troops to integrate the University of Mississippi by force, leading to two deaths and hundreds of serious injuries). The forces of reaction have, historically, not been inclined to adopt a properly “ironic” and reflexive relationship to political conflict, and it seems highly unlikely that they could be brought to do so by exposure to the right kind of political philosophy.

“In fact this has always been their role and it is only the modernist illusion of the privileged position of the artist that has made us believe otherwise. Once this illusion is abandoned, jointly with the revolutionary conception of politics accompanying it, we can see that critical artistic practices represent an important dimension of democratic politics.” Chantal Mouffe, “Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces,” Art & Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods 1 (Summer 2007): 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 4. Mouffe’s use of agonism as a model for political discourse can be read against Renato Poggioli’s thoughtful analysis of “agonistic sacrifice” (on behalf of “the people,” posterity, and so forth) as a key component of the modern artistic avant-garde. Renato Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Gerald Fitzgerald (Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard University Press, 1968), 61–77.

At the same time, Mouffe charges art with the task of “giving a voice to all those who are silenced within the framework of the existing hegemony.” Thus, art is simultaneously the mechanism by which the repressed will be brought to consciousness (via the disclosure of “that which has been repressed”) and the channel by which these same individuals will be “given” a voice. This confusion is symptomatic of the tensions I outlined earlier in my discussion of vanguard politics. Mouffe, “Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces,” 4–5.

An instructive comparison can be made here between Occupy Wall Street (OWS), which is at this stage only very loosely organized, and the extremely disciplined command structure of the Republican Party and it’s affiliated “activists” in the United States. A typical example is the REDMAP Project (REDistricting Majority Project) of the Republican State Leadership Council, which is developing a set of coordinated strategies to exploit the re-districting process in order to ensure Republican domination even in states with Democratic majorities. The far right wing in the United States has consistently exhibited a sophisticated understanding of the interrelated mechanisms of local, regional and national governance at both the symbolic and the institutional level, extending to active involvement in school board and town council elections. This “ground up” activism, combined with a well coordinated system of message control and a centralized national leadership, has led to the creation of a formidable political machine that has been able to secure remarkably widespread support among working-class and lower middle-class voters for a pro-corporatist message in the midst of the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression. The pervasive success of this machine makes the ability of the OWS movement to mobilize a passionate, albeit unfocused, resistance to capitalism all the more remarkable.

Bishop disparages “the ethics of authorial renunciation,” which she associates with collaborative art practices. Bishop, “The Social Turn,” 181.

The preceding quotes are all from “The Social Turn,” 180–181. Bishop complains elsewhere of criticism in which “Authorial intentionality is privileged over a discussion of the works’ conceptual significance as a social and aesthetic form … Emphasis is shifted from the disruptive specificity of a given work and onto a generalized set of moral precepts.” Ibid., 181. Bishop appears to confuse the fact that some artists have a more reflective or critical relationship to conventions of artistic agency with an absolute abandonment of the prerogatives of authorship in toto. Most contemporary artists who work through a collaborative or collective process don’t do so because of their allegiance to an abstract moral principle, but because they find that these processes result in more interesting and challenging projects, or provide forms of insight that are different from those generated by singular forms of expression.

“Sierra’s action disrupted the art audience’s sense of identity, which is founded precisely on unspoken racial and class exclusions, as well as veiling blatant commerce.” Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” 73.

Ibid., 70.

Julia Austin, “Trauma, Antagonism, and the Bodies of Others: A Dialogue on Delegated Performance,” Performance Paradigm 5 (May 2009): 4. See →.

While Bishop applauds Sierra for evoking a sense of “liberal guilt” in the viewer, she also praises artists such as Jeremy Deller, Phil Collins, and Christian Höller for not making “the ‘correct’ ethical choice … instead they act on their desire without the incapacitating restrictions of guilt.” Bishop, “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents,” 183. The distinction here is clear. While the artist may have transcended the humanist burden of “guilt,” the viewer has not.

See Grant Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Duke University Press, 2011).