The following text, which is the first of three installments, traces back to a conversation I had with Mike Kelley in 1994, “Too Young to be a Hippy, Too Old to be a Punk.”1 Christophe Tannert at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin had invited us to discuss underground political and aesthetic culture in the US for the first issue of Bethanien’s Be Magazin. One year later, I followed this up with a narrative account and analysis of the subject, “Burying the Underground.” Meanwhile, a series of sieges, armed standoffs, and bombings made Americans increasingly aware of a growing polarization between the US federal government and what was hardening into a grassroots militia movement: Ruby Ridge (1992), Waco (1993), Oklahoma City (1995), and Fort Davis, Texas (1997). I began to see this as a right-wing counterpart to militant leftism. In fact, the Right seemed to be mirroring tactics that the leftist underground had initiated. This led me to write a complementary essay, “Heil Hitler! Have a Nice Day! The Politics of Hate in the USA.” By 2001, the militia movement had run out of steam. When al-Qaeda terrorists staged the 9/11 attacks, however, these so closely resembled events described in The Turner Diaries that I had initially suspected the radical Right. Although unemployment and economic dislocation drove the militia movement of the 1990s, the Great Recession has not provoked a similar response. Instead of overturning—or seceding from—the federal government, the Far Right, now exemplified by the Tea Party, wants to work from within the political system by downsizing government and converting it to a states’ rights model. This shift is evident in the current Republican debates leading up to the next presidential election, where candidates have tried to turn “moderate” into a pejorative term.

—John Miller

***

There exists a subterranean world where pathological fantasies disguised as ideas are churned out by crooks and half-educated fanatics for the benefit of the ignorant and superstitious. There are times when this underworld emerges from the depths and suddenly fascinates, captures, and dominates multitudes of usually sane and responsible people, who thereupon take leave of sanity and responsibility.

—Norman Cohn2

Although the American extremist Right is small in numbers, it exerts a disproportionate ideological influence both domestically and internationally. Although built on outlandish claims, the rhetoric of the militant Right quickly becomes repetitive and stultifying, and people should not underestimate the danger it poses. Its ridiculousness conceals a violence and divisiveness which are clearly aimed at mainstream and progressive, liberal-democratic values in the United States. Ideological tautologies upheld by constitutionalists, apocalypticists, and conspiracy theorists preclude the very possibility of debate and social discourse. By mythifying the issues it supposedly addresses, the Right polarizes discourse. This, in turn, only naturalizes the issues and insulates their construction from public scrutiny and criticism. Once such myths are in place, veracity is beside the point and ideological questions are no longer open to debate.

Historically, the radical Right’s new momentum appears as a backlash against New Left political gains of the 1960s and ‘70s. Instead of a nineteenth century–style revolution defined against the governance of a nation-state, the New Left pursued a revolution in everyday life which entailed the desublimation of what were predominantly patriarchal or imperialist social institutions. To a certain extent, it succeeded. Nevertheless, declining standards of living and economic dislocations have embittered many—typically middle-class white men, who still view themselves as the majority—depriving them of what they regard as their birthright. Under growing financial pressure, they see the new post-colonial global economy as an insidious plot and the social ascendence of women and minorities as an unfair erosion of their rightful status. The proletarianization of America’s middle class results from two related but assymetrical factors: the steady equalization of the world economy, and the Reagan Revolution’s drastic consolidation of wealth within a ruling class elite. Although the United States has the highest per capita consumption of global resources, the gap between its rich and poor is significantly wider than in industrialized Europe. Even so, certain Americans continue to regard theirs as an egalitarian society, so long as these rights are restricted to Christians of European descent. For them, the class structure of American society is invisible. Thus, they would sooner attack immigrants, African-Americans, Jews—or even the government—than criticize the ruling class.

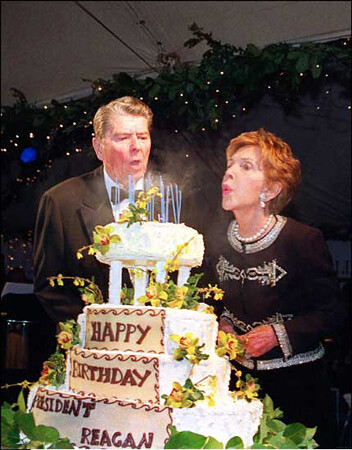

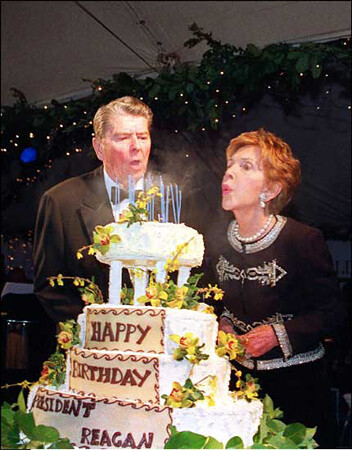

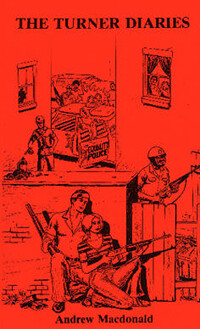

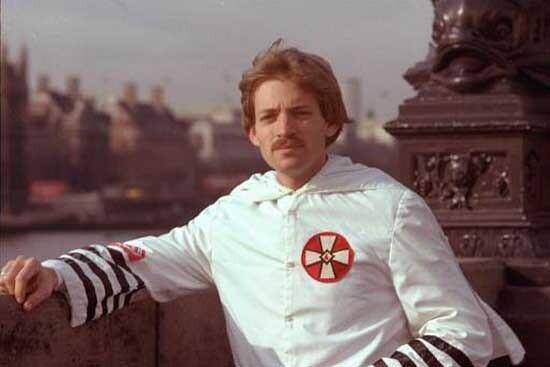

Ronald Reagan and George Bush coined the phrase “Vietnam syndrome” to put pacifism to rest within the United States once and for all. Little did they know that “the syndrome” was even more pronounced in militaristic, right-wing America where many felt that if the US Army ever lost a war, it could only result from some kind of government conspiracy. Chief among these conspiracy theorists was former Green Beret and Vietnam veteran Lt. James “Bo” Gritz, who was one-time Klansman David Duke’s Populist Party running mate in the 1988 presidential election.3 Ironically, the militarization of the Right occured largely in reaction to that of the Left. By adopting Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s “foco theory” (which postulated that a small group of armed guerillas can set a popular movement in motion), the American Left inadvertently furnished the Right with a seductive terrorist model. Besides an armed struggle, foco theory also demanded the immediate transformation of everyday life—not its postponement until “after the revolution.”4 While the New Left shared the need to transform the habitual norms of everyday life, its adoption of foco theory ultimately redirected American activism toward the more old-fashioned and less realistic goal of an armed overthrow of the state. Radical resistance went from Ghandian nonviolence to a cynical romanticization of murder—what George Katisaficas called a “psychic Thermidor.” Instead of starting a progressive mass movement, foco theory fragmented the New Left, just as the momentum for feminism, gay rights, and civil rights was strongest. By the mid-1980s, the “foco” approach as a transformative strategy had even played itself out in Latin America. Against a backdrop of liberal hypocrisy, a politics of hate held out only the promise of existential authenticity for all political extremists. Indeed, William Pierce’s infamous misantrhopic novel, The Turner Diaries, ultimately echoes the tactics of Che. In this book, Pierce offered a futuristic vision of an African-American takeover of the white population and an ensuing race war. Although fiction, the book later served as a template for all-too-real terrorist acts:

More and more, the government will lash out at dissidents, at anyone who is not politically correct. And the two sides will feed on each other. The more repressive and terroristic the government becomes, the more individuals there will be who will engage in terrorism to get back at the government. And the more individual terrorism there is against the government, the more terroristic the government will become, in turn.5

In both instances, one might call this, after Walter Benjamin, an endgame of the aestheticization of politics. Even more recently, Ruby Ridge, Waco, and Oklahoma City have shown that to respond to violence with overwhelming force can be disastrous in a climate of right-wing provocation. The patient courage of Morris Dees of the Southern Poverty Law Center suggests more effective tactics: through class action lawsuits Dees shut down several arms of the Ku Klux Klan and Tom Metzger’s White Aryan Resistance.

By the mid-1970s, Herbert Marcuse’s theories—which had been so intimately part of the American New Left of the 1960s—began to fall from favor. Nonetheless, Marcuse’s key concepts can help articulate significant differences between the right and left versions of the underground. Repressive intolerance, of course, continually serves to unmask the seemingly benign aspects of liberal ideology. The eros effect, however, is even more significant when read against the grain. Marcuse linked the eros effect, for example, to the events of May 1968.6 Those, however, were extraordinary times and social ideals alone are insufficient to mobilize the masses. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the breakdown of the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc. The political collapse of the communist economies stems in part from the failure of the collective social good to sustain a libidinal investment commensurate with the effects solicited by the commodity form. What this suggests is a particular binding of the political at the level of libidinal investment, which is necessarily a central concern of aesthetics as well: what is beautiful, what is desirable, what is valuable, and so forth. While the left-wing underground paradigm was both political and aesthetic, that of the American Right is nominally only political and religious. In right-wing American movements, therefore, religion reabsorbs secular aesthetics. This suggests that contemporary political struggle largely concerns the desublimation and re-sublimation of everyday life. (It may also explain why the elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts, whose budget became so small as to be only symbolic, was such an important goal for the Right to eliminate.)

Progressive politics still entails politicizing aesthetics while reactionary politics does the reverse: aesthetizing politics. In the United States, religion plays a large part in this question. If socialism derives generally from the religious doctrine of agape, the hatred of the radical Right derives from denying the guilty truths of American culture. Here, God fills the aporia of historical repression. The Identity Christian, for example, invokes the name of God to construct a hermetic system—which in turn justifies a sordid history of racist exploitation.7 The irruption of the radical Right onto the American political landscape shows that the struggle to transform everyday life concerns not just the problems of consumer society. It must necessarily confront the legacies of colonialism and genocide as well.

In the postwar United States, and largely through the media efforts of the 1970s and ‘80s, the figure of the German Nazi came to personify evil. Naturally, this symbolization was meant to register enduring revulsion for the genocide of the Third Reich. Even so, it has also served to mythify Germany as the origin and baseline for all evil, blinding many to fascist realpolitiks elsewhere in the world—especially at home. Conversely, many apply the term “fascist” too often and too indiscriminately; now it may only mean something someone does not like. Yet the image of the jack-booted storm trooper, straight out of central casting, eclipses that of the talk radio demagogue or the weekend warrior-consumer. Consequently, fascism comes to seem less and less traceable to everyday contradictions of capitalist political economy, especially those of economic recession and declining standards of living. Consider how the skinhead movement theatricalizes the image of evil anew in pop culture. Ironically, skinhead style derives from the Mods, who at first hyperbolized and rejected normality with ties a little too thin and grooming a little too clean cut. Yet, for the Far Right, the very idea of individual stylization appears beside the point after religion reabsorbs aesthetics. Thus, the Right considers itself wholly natural and normal: a kind of normality concerning more the repressive wholesomeness of a puritanical ethos than goose stepping and swastikas. The Far Right, in other words, believes itself to be entirely without artifice. Even Aryan Nations’ Richard Butler put together his uniforms (outfits?) from the poly-blend selections at the local J.C. Penney’s. This “anti-aesthetic” sharply distinguishes fascist tendencies in the United States from those in Germany. Filmmaker Hans-Jürgen Syberberg maintains that the ultimate goal of National Socialism was not only to unify German people and culture, but also to transform that people and culture into a manipulable aesthetic object. In the United States vehement religiosity instead creates broad ideological cohesion within the movement. (The word religion derives from the Latin religare, “to bind together.”) Nevertheless, followers see themselves as highly individualistic, not conformist. Because the United States began as a nation of religious refugees, for many religion and the notion of individual freedom remain inseparable.

Although a broad sector of the American public may be conservative, only a small number is extremist. An even smaller segment of this extreme ever engages in terrorism. Most extremist groups are narrowly focused. Sometimes, they are antagonistic; sometimes their interests overlap. Fundamentalist preachers Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell, for example, are pro-Israel—which pits them against more radical anti-Semitic Christian organizations. Still others, such as the Order’s Robert Mathews, while anti-Semitic, do not especially consider themselves “Christian.” (Mathews was an avowed believer in the Norse god, Odin.) An income tax resister need not support prayer in public schools. Nor would a militant right-to-lifer necessarily oppose immigration. For that matter, a libertarian would, on principle, reject both government-funded abortion clinics and any restriction on a woman’s right to choose. Given the marked heterogeneity and fragmentation of this social field, one must view it in at least two ways: through a mapping of constituent issues and through a narrative account of constituent movements and organizations.

Populism

Populism, by definition, is anti-elitist: favoring individuals and local municipalities over large corporations and big government. In postwar politics it represents a backlash against the dislocations of transnational capital and the regimentation of mass culture. It typically champions a politics of independent production, exemplified by the small farmer’s idealized self-sufficiency versus urban consumer culture.8

In a democratic society, politicians necessarily seek a broad base of popular support. To achieve this, they often claim “to speak for the common man.” Just who that may be, however, is highly malleable. At the outset, at least, it is also a projection and, to a certain extent, a function of the imaginary. Invoking the name of “the people” (versus the Marxist term masses) remains a vague gesture by itself. An adept rhetorician can seemingly bend “the will of the people” to the most inscrutable ends. Anti-corporate, anti-establishment, and anti-Eastern, the most notable populist politicians are characteristically third party candidates: William Jennings Bryan, George Wallace, Jesse Jackson, or Ross Perot. Essentially neither left nor right, the populist rejection of the mainstream sometimes lurches unexpectedly toward extremism. There, populist, socialist, and reactionary tendencies may dovetail. In 1968, for example, most Wallace supporters named Robert Kennedy their second choice for president. (Wallace himself later renounced his racism before Martin Luther King’s former congregation.)

America’s most colorful populist was Huey Long. A Louisiana governor and US Senator, Long ran for president in 1934 under a “Share Our Wealth” platform to nationally redistribute capital. His most ardent campaigner was the fundamentalist preacher Gerald K. Smith. Smith idolized Long and, during the campaign, often slept at the foot of his bed. When he was shot, Long died in Smith’s arms. A brilliant orator, Smith later embraced Christian Identity theology and became modern America’s chief proponent of anti-Semitism. His influence spans from the 1930s to the present. When David Duke mounted his presidential campaign with the aforementioned Bo Gritz as his running mate, the Populist Party tried to state its platform in a way meant not to sound racist. Nonetheless, a peculiar need to state opposition to slavery, and phrases like “free from interference from another race” belie its nominal tolerance:

RESPECT RACIAL AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY. Every race has both the right and duty to pursue its destiny free from interference by another race. The Populist Party opposes slavery, imperialist exploitation, social programs which would radically modify another race’s behavior, demands by one race for another to subsidize it financially or politically as long as it remains on American soil, forced segregation or integration. The Populist Party will not permit any racial minority, through control of the media, culture distortion or revolutionary political activity, to divide or factionalize the majority of the society-nation in which the minority lives.9

An appeal to tradition, however, sanctions a more blatant bias toward women and gays:

REJECT ERA AND GAY RIGHTS. Legally women already have more rights than men, and that is the way the Populist Party intends to keep it. Homosexuality is not only immoral, it is perversion and should not be recognized as a legitimate life style deserving special legislation and [sic] forcing normal people to accept them. The Populist Party recognizes a responsibility to fight this growing social disease.10

American Transcendentalist philosophy inflects populism of the dissident variety. Seeing society as “a conspiracy against its individuals,” populist militants presume the moral right and obligation to take action against big institutions. In the nineteenth century movement anarcho-capitalism, Lysander Spooner espoused the ultimate extreme: two men have no more natural right to exercise any kind of authority over one, than one has to exercise any kind of authority over two. A man’s natural rights are his own, against the whole world.”11

The Family and Education

The question of “family” values concerns a cluster of such debates as home schooling, sex education, gender roles, and the so-called right to life. Here, the radical Right invokes an exclusively heterosexual, white, middle-class model of the nuclear family to justify its hatred of abortion, gay rights, and integration. The John Birch Society posits the family as: civilization’s most basic social unit; its most fundamental economic unit; and “the child’s first and most important school.” These it contrasts with the Communist Manifesto’s demands for abolition of inheritance rights and for free education in public schools.12 John Birch Society writer, Medford Evans, further stipulates an “inherent” reciprocity between the institutions of family and nation:

There is indeed an inherent and indestructible relationship between the very concept of family and that of nation. The word nation is derived from the past participle of the Latin verb nascor, nati, natus, meaning to be born. Which is reminiscent of the fact that patriotism is derived from the Latin patria, fatherland, from pater, father. There can be no denial that the very idea of political sovereignty, and thus of all lesser legal authority, is inextricably fused with the idea of blood kin, of family, of parental responsibility and authority.13

The term “blood kin” underscores the racial factor in this equation. Fears of miscegenation abound as well. White supremacists, in particular, view abortion and zero population growth as insidious plots to reduce and disenfranchise America’s white population. Their opposition to abortion clinics and family planning organizations includes protests and bombs. The struggle over abortion stepped up when pro-life activist Randall Terry launched Operation Rescue in 1987. Operation Rescue used civil disobedience—typically blockading abortion clinics—in its campaign against the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. On March 10, 1993, such activism turned to murder when Michael Griffin murdered Dr. David Gunn in Pensacola, Florida. On July 24, 1994, the defrocked minister Paul Hill then killed Gunn’s replacement, Dr. John Britton, and his bodyguard, James Barret. The following December 30, John Salvi III went on a two-day rampage against clinics in Brookline, Massachusetts, and Norfolk, Virginia, killing three people and wounding five others.14 White Aryan Resistance leader Tom Metzger encouraged such attacks:

Almost all abortion doctors are Jews. Abortion makes money for Jews. Almost all abortion nurses are lesbians. Abortion gives thrills to lesbians. Abortion in Orange County [California] is promoted by the corrupt Jewish organization called Planned Parenthood… Jews must be punished for this holocaust of white children.15

The racist ideology of functionalist procreation of course militates against homosexuality as well. The gay community, for its part, has long been the target of less programmatic, yet more consistent and more generalized “spontaneous” violence: gay bashing. Undoubtedly, attacks on African-Americans have been by far the most generalized and the most pervasive. Some have even been supported by nominally mainstream authorities. In 1957, when federal authorities first bused African-American children to integrate a school in Little Rock, Arkansas, local officials tried to block the move. To enforce the new federal statute, the Eisenhower administration called in National Guard troops. After this, white supremacists increasingly regarded the federal government as their enemy.

The extreme Right particularly blames John Dewey for shaping—and corrupting—modern public school education. The US Constitution stipulates, as an essential principle, the separation of church and state. As a socialist, Dewey advocated further secularizing public schooling: “There is no God and there is no soul. Hence there are no needs for the props of traditional religion. With dogma and creed excluded then immutable truth is also dead and buried. There is no room for fixed natural law or permanent moral absolutes.”16 Fundamentalists in turn charge that, far from refusing to teach religion, the American school system teaches humanism as a new religion. They trace every educational reform back to Dewey’s atheistic influence—particularly sensitivity training which teachers use to promote racial and cultural tolerance. This, they liken to “brainwashing” techniques purportedly used by the Chinese military during the Korean War. Some even see sex education as a Jewish instrument of moral corruption. Finally, the Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Ford Foundations’ sponsorship of progressive school reforms sparks rumors of a sinister conspiracy funded by international capital. Thus, many prefer to school their children at home according to their own particular values.

Constitutionality

Those unfamiliar with the “patriot” movement’s rhetoric may at times find it paradoxical: “The US Government is lawless.” “Agents of the Internal Revenue Service are traitors.” And so on. Such ideas stem from a radical “states rights” reading of the US Constitution, which, surprisingly, is not always altogether unfounded. Many polemicists treat this document as Holy Writ, appealing to the authority of the framers—or Founding Fathers—who signed it. Right and Left, of course, interpret it differently and focus on different parts. Significantly, the Posse Comitatus and others believe that God literally bestowed the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights (the Constitution’s first ten amendments) on the American people. Constitutional fundamentalists, like their Biblical counterparts, stress a literal interpretation of the written word to the exclusion of all else. Quoting selectively, they eliminate unwanted ambiguities and contradictions—plus an entire history of struggle and compromise, which, even today, is far from over. In so doing, they construct a closed system of thought, with which they treat contrary interpretations from jurists, historians, and legal scholars with contempt.17

Predictably, those who view the Constitution as God’s creation resent changing it. For them, the Civil War is the cutoff point. They believe that the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of 1868 (which respectively prohibited slavery and guaranteed universal civil rights) only corrupt the original document. Subsequent amendments against poll taxes and discrimination only make matters worse. Not surprisingly, these are the very amendments which safeguard the civil and political rights of women and minorities. White supremacists, moreover, distinguish between so-called “state citizens,” white Americans whose rights “derive from God,” and “Fourteenth Amendment citizens” whose rights derive from a suspect federal government.18 They urge state citizens to claim their God-given sovereignty by renouncing their presumed Fourteenth Amendment citizenship and by breaking all established contracts with the federal government. Such “unlawful” contracts include Social Security cards, driver’s licenses, marriage licenses, birth certificates, passports, and other legal documents. In so doing, they recognize only common law; Fourteenth Amendment citizens, however, must continue to abide by all federal and state laws. Richard Abanes has described how the so-called constitutionalists base their interpretations on logical fallacies:

Patriot arguments in the courtroom often make little sense because they commonly employ a logical fallacy known as “making a distinction without a difference.” This happens when a particular issue is being discussed, and then that same issue is identified as something entirely different by making a meaningless distinction. Tax protesters, for example, admit that United States citizens do indeed have to pay taxes on income, but that they, as sovereigns, do not earn income. They receive wages. Consequently, patriots do not have to pay taxes.19

Income tax is as contentious as civil rights legislation. Its opponents correctly identify it as a prime source of the federal government’s power; without income tax revenues, the government would have to close down. Thus, income tax resistance offers a highly effective form of political protest. Despite its seeming indispensability, income tax is a recent, postwar institution. In 1913, Congress had already passed the Sixteenth Amendment granting the federal government the right to levy and to collect income tax. Nonetheless, the Roosevelt administration became the first to impose it as an emergency “victory tax” to help cover the costs of World War II. Since then, income tax has remained in place. Citing Article 1 of the Constitution, the Patriot Network and other groups claim that the Internal Revenue Service is unconstitutional and that paying federal income tax should be voluntary. The Far Right further considers the Federal Reserve Board, conceived by the German-born Paul Warburg, as an illegal instrument of global conspiracy. It considers Federal Reserve Notes a particularly onerous tool for economic domination. Some insist that gold and silver coins are the only valid form of currency.20

Central to the patriot movement is the question of sovereignty, that is, which level of government holds the highest authority. Before the Constitution, the United States was governed by the Articles of Confederation. Under these, Article 2 granted extensive power to individual states: “Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.”21 Federalists believed these restrictions excessively weakened the President and Congress. The resulting debate over how to allocate power through the Constitution reflected a division between populists and the elite. Populist advocates were further split between North and South. The New England model generally favored local, popular government (through “town meetings”) while the Southern state’s rights model served to protect the autonomy of the plantation system and the institution of slavery. In drafting the Constitution, the Federalists nonetheless held sway, giving the federal government far more sweeping powers than had the Articles. They agreed to add the Tenth Amendment, however, as a compromise. It stated, somewhat unclearly, “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people [italics mine].” Many have ignored or overlooked this final phrase, but not the radical Right.

Despite the enduring Federalist legacy, it was the small farmer’s struggle against the elite that precipitated the American Revolution. Colonial patriots took the law into their own hands not for the sake of abstract democratic ideals, but to protect their property and their means of livelihood. In Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676, Virginia frontiersmen defied the British government and massacred Native Americans for the sake of gaining land and freedom from aristocratic control. (Their hatred for Native Americans also laid the ideological groundwork for slavery.) Between 1650 and 1850, frontiersmen rose no less than sixty times to protest unfair land laws. They formed their own militias to burn stores, public buildings, and well-to-do homes, to close down local governments and start their own. These uprisings included Shay’s Rebellion and the Whiskey Rebellion. Even so, Richard Abanes points out that to compare today’s legislative irritations with the widespread sufferings endured by the colonialists is wrong and “an insult to the memory of America’s founders.”22 Moreover, the militias of the Revolutionary War were neither clandestine nor unregulated; members signed muster rolls that bound them to the articles of war and they drew wages from public treasuries. Ethan Allen, however, negotiated with Great Britain to recognize the independent State of Vermont both before and after the Revolution. In such a spirit, the Posse Comitatus, the Montana Freemen, and others assert that the highest level of legitimate government rests with the county sheriff. The Posse, moreover, traces the sheriff’s authority back to God:

The prerequisite to proper guidance is the basic understanding of Common Law and a background knowledge of the United States Constitution. … Such knowledge is … essential to good citizenship and fulfillment of the responsibilities by true Christians to their God and Country. … The Constitution was lifted from the articles of Confederation, therefore the Constitution’s source is the Holy Bible.23

From there, Posse legalism lurches into unbridled paranoia:

We are facing a lawless group in power who are in the process of destroying our freedoms and making us serfs of a ONE-WORLD GOVERNMENT, ruled by the ANTI-CHRIST.24

This shows the ease with which Constitutional fundamentalism can jump from legal minutiae to overarching cosmologies. Even so, the desire for a close reading of the Constitution can arise from geopolitics. Global capital’s redefinition of the nation state threatens to destabilize traditional identities both inside the United States and abroad. The attempt to anchor power absolutely at the local level represents—symbolically or otherwise—a last ditch effort to reverse this process. Because the patriot movement so strongly considers itself to consist of “true” Americans, it concludes that the bewildering problems of globalization could only result from covert government betrayal.

Gun Control

The Second Amendment states that “[a] well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” While this right is seemingly enshrined as a legacy of the Revolutionary War, it has become the most widely debated part of the Constitution, deeply dividing the American public. Gun culture is a legacy of frontier justice—and, by extension, has come to represent individual liberty. Even so, the proliferation of automatic weapons has turned some American cities into veritable war zones. The National Rifle Association (NRA), Gun Owners of America, and other lobbies nonetheless cast any attempt to restrict the possession or sale of firearms as an erosion of fundamental American freedoms. This issue is crucial to rightist militants. Clearly, without access to military-grade weaponry, the militia movement would cease to exist. Norman Olson, a Baptist minister who founded the Michigan Militia, maintains, “[t]he Second Amendment is really the First in our country, because without guns for protection from tyrants, we would have no free speech.”25 The NRA’s best known slogan is “If possession of guns becomes a crime, then only criminals will have guns.” Former Chief Justice Warren Burger, however, called the gun lobby’s interpretation of the Second Amendment:

one of the greatest pieces of fraud, I repeat the word “fraud,” on the American public by special interest groups that I’ve ever seen in my lifetime.

The real purpose of the Second Amendment was to ensure that the state armies—the militias—would be maintained for the defense of the state. The very language of the Second Amendment refutes any argument that it was intended to guarantee every citizen an unfettered right to any kind of weapon he or she desires.26

The American Civil Liberties Union also believes that nothing in the Constitution guarantees the right to bear arms. Conservatives argue, however, that this was the intent of the Founding Fathers, citing declarations from Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, James Madison, and Samuel Adams.27

The first firearms regulation, adopted during Prohibition, levied a special tax on the machine guns and sawed-off shotguns then favored by gangsters. Following the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, Congress passed the Gun Control Act of 1968. It then redirected about one fourth of the agents in the Treasury Department’s Alcohol Tax Unit to enforce firearms regulations. In 1969, the department renamed the unit the Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Division. Shortly after, the Nixon administration reorganized it as the current Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (BATF). After David Hinkley’s failed assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan in 1981, pressure for stricter gun control again increased. In 1993, shortly after the fateful shootout at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, where US Marshals and FBI agents killed Aryan Nations member Randy Weaver’s wife and son, the Clinton administration finally managed to pass the Brady Bill, a measure requiring a waiting period for the purchase of handguns.28 Ruby Ridge, in turn, became a rallying point for the growing militia movement in the United States. The Federal Crime Bill followed in 1994, further curbing sales and ownership of assault weapons. Efforts to police firearms, however, touched off another massive disaster: Waco. The BATF played a key role in both.29

This, then, represents a mapping of the key social issues around which the right-wing underground is organized: populism, the family, constitutional fundamentalism, and the right to bear arms. The second part of this series will examine the genealogy of beliefs that serves to justify these positions.

“Too Young to be a Hippy, Too Old to be a Punk. (Discussion with Mike Kelley),” Be Magazin, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, vol. 1, no. 1, 1994, p. 119–123 (English), p. 124–129 (German).

Norman Cohn, quoted in Daniel Levitas, “Sleeping with the Enemy: A.D.L. and the Christian Right,” The Nation, June 19, 1995: 888.

“Green Berets” is another name for the U.S. Army’s elite Special Forces unit, trained in guerilla warfare and hi-tech weaponry. Bo Gritz is the flamboyant veteran on whom the Rambo movies are said to be based. Gritz became disenchanted with the U.S. government when he discovered high-level American officials were purchasing opium from a Burmese warlord and that the CIA was trafficking cocaine in Latin America to finance covert operations there. This led him to embrace conspiracy theory. He ran for president as the Populist Party candidate in 1992. Alan W. Block, “The Standoff,” Ambush at Ruby Ridge(New York: Berkley Books, 1995), 85-86.

George Katsiaficas, “Social Movements of 1968,” The Imagination of the New Left: a Global Analysis of 1968 (Boston: South End Press, 1987), 36-3.

Morris Dees, “The Last Best Hope,” in Dees with James Corcoran, Gathering Storm: America’s Militia Threat (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1996), 228-29.

Already recognized by the student left at Brandeis University in the 1950s, Herbert Marcuse theorized the eros effect as the potential for a collective human consciousness to arise spontaneously and transcend the short-term values of modern society. In place of categorical divisions and competitive modes of chronic self-interest, this effect would seek to construct social relations based first in concerns for universal prosperity and well-being. See Herbert Marcuse,Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1955).

For one history of the Christian Identity movement see Michael Barkun, Religion and the Racist Right: The Origins of the Christian Identity Movement(Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

See Catherine McNicol Stock, “The Politics of Producerism,” Rural Radicals: Righteous Rage in the American Grain (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), 15-86.

“Populist Party Platform,” Extremism in America, Lyman Tower Sargent, ed. (New York: New York University Press, 1995), 20.

“Populist Party Platform,” 20. Section One of the proposed Equal Rights Amendment stated: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” The ERA was introduced in 1923 but not passed by the Senate until 1972. After twenty-two states quickly ratified it, Phyllis Schlafly’s organizations, the Eagle Forum and STOP ERA, rallied opposition against it. The ERA failed to reach the necessary thirty-eight state minimum for ratification.

Sargent, “Introduction,” 11.

Reed Benson and Robert Lee, “Your Family: the Fight for America Begins at Home,” Extremism in America, 213-3.

Medford Evans, “Childcare: the Great Federal Kidnap Conspiracy,” Extremism in America, 204.

Richard Abanes, “Holy Wars,” America’s Militias: Rebellion, Racism, Religion (Downers Grove, Illinois: Intervarsity Press, 1996), 214-215.

Tom Metzger quoted in Abanes, “Holy Wars,” 217.

Gary Allen, “New Education: the Radicals are After Your Children,” Extremism in America, 225.

Bennett, “Reshaping of the New Right, Rise of the Militia Movement,” 452-453

Ibid, 443-44.

Richard Abanes, “Sovereign Citizens Rebellion,” American Militias: Rebellion, Racism, Religion (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 36. See Abanes, 30-32 for a discussion of Fourteenth Amendment citizens.

Ironically, the Grange Movement advocated printing more paper money as part of a cheap money policy which would enable farmers to more easily pay off their debts

Sargent, “Introduction,” 4.

Abanes, “Guns, Government, and Glory,” 70.

Posse Comitatus, “It is the Duty of Government to Prevent Injustice—Not to Promote It,” Extremism in America, 346.

Ibid, 348.

Quoted by Dees and Corcoran, “Militia Warriors,” in Gathering Storm, 87.

Dees, “The Last Best Hope,” in Gathering Storm, 220-21.

Abanes, “Guns, Government and Glory,”

The bill was named after Reagan’s former press secretary, James Brady, whom Hinkley shot and left partially paralyzed. Brady then became a strong advocate of gun control. The Brady Law bans sales of several types of assault weapons and requires background checks before guns can be purchased.

Alan W. Bock, “A Government Out of Control?” Ambush at Ruby Ridge (New York: Berkley Books, 1995), 275.

To be continued in Politics of Hate in the USA, Part II.