We are in the middle of a time in which classical notions of flexibility and freedom actually work to alienate our relations to one another. But in fact the ability to shift, to deviate, to morph should constitute the strongest claim that we are much more than what traditional categories tell us we must only be. It is precisely when elaborate techniques of labor extraction become indistinguishable from sensations of pleasure and self-realization that queerness returns to insist on the freedom to move and the freedom to be what one is and what one wants to be—not as a matter of belief but as a matter of survival. Because we can only see new worlds and new ways of life when we are able to be ourselves, to move between cultural, sexual, or civic roles without being defined by any single one. When this is blocked off, we can barely even see the world as it already is. As normative structures themselves collapse this only becomes more clear as our our bodies, minds, sexualities, and relations to the material world become unstable and start to marble and mingle. In fact we are all coming out of the closet and becoming queer. Some did it long ago, and as forms of exploitation evolve and adapt it becomes clear that taking a queer stance is not any easier today than it was then. This month we’re really honored to have artist Carlos Motta guest-edit “(Im)practical (Im)possibilities,” a very special, very queer April issue of e-flux journal.

—Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood, Anton Vidokle

But, bottom line, this is my own feeling of urgency and need; bottom line, emotionally, even a tiny charcoal scratching done as a gesture to mark a person’s response to this epidemic means whole worlds to me if it is hung in public; bottom line, each and every gesture carries a reverberation that is meaningful in its diversity; bottom line, we have to find our own forms of gesture and communication—you can never depend on the mass media to reflect us or our needs or our states of mind; bottom line, with enough gestures we can deafen the satellites and lift the curtains surrounding the control room.

—David Wojnarowicz, Postcards from America: X-Rays from Hell (1989)

At the age of seventeen I picked up a copy of Close to the Knives, David Wojnarowicz’s “memoir of disintegration,” and found an intensely apocalyptic vision of the world that felt terrifyingly real, confident, and uncompromising. That was the moment I started to understand that my personal struggle as a gay boy growing up in a Catholic South American country was part of a much larger political struggle. And it was then that I was able to name the injustice of the system towards queer lives, and my own feeling of urgency with regard to it. Wojnarowicz made the convergence between rage, ideals for a good life, and political commitment evident and urgent: a refusal, despite the discouraging state of things, to adapt to the forces of oppression.

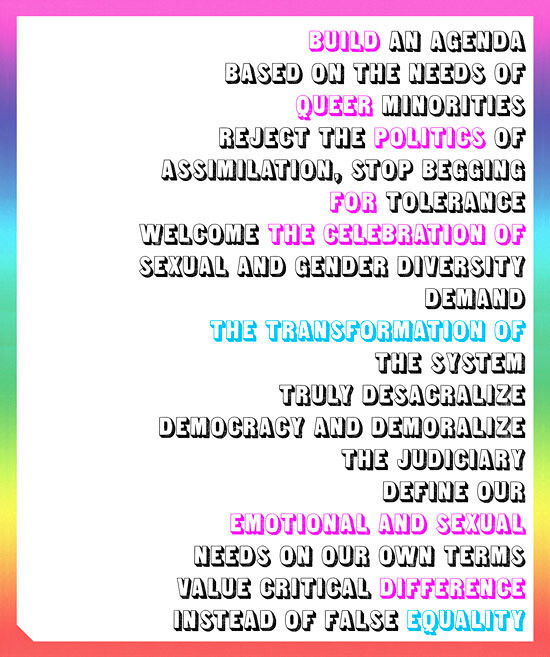

We live in a time of pervasive conformity and strategic pragmatism where, rather than challenge and transform those very structures that have historically denied our (deviant) identities and (feared) bodies, the political aim of mainstream Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex (LGBTI) movements now consists of begging for inclusion in discriminatory legislative, social, religious, and cultural systems. The idea of “equality” has been hijacked by homonormative career bureaucrats who conform to existing systemic protocols, sacrificing the hope of a truly mutable sexual and gender revolution.

Ideas of radical change tend to be regarded as naive and outdated in our increasingly normalized neoliberal climate. Progress is equated with assimilation, and individual and community rights are mostly available to socially and economically privileged sexual minorities who have the resources to be visible. The mainstream LGBTI movement’s moderate approach, where identity-recognition and tolerance are the foundation of the battle for legal rights, has proven insufficient to confront issues of poverty, disability, criminalization, discrimination, and other forms of oppression that the majority of queer people face. This political inequality and cultural complacency must compel us to insist that social issues are queer issues and that social injustice is queer injustice.

But reductive binary discourses fail to acknowledge the nuances of the way power operates in society. They simplify the perverse ramifications of political manipulation, to the extent that attaining justice may in fact be impossible within the current structure and its institutions. Queer people around the world resist the appeal of the “moderate” mainstream LGBTI movement and its pillar issues, like marriage equality—a battle that demonstrates how an incremental approach to change developed on the terms of institutionalized bureaucracy reproduces systemic disparity. Marriage privatizes social safety nets, destabilizes the bonds of the welfare state, and creates a culture of self-reliance that perpetuates economic inequality.1 Marriage is often discussed as being about love and sentimental commitment, and legal and moral rights are extended to subjects who conform to a conventional understanding of what a union between people can be. Only two people, preferably a man and a woman, who (faithfully) commit for eternity can be granted access to innumerable social and legal benefits. Those who have not, by fate or by choice, adjusted to that dictate are marginalized by the law and sanctioned by normative morality. Thus, our imperative becomes mobilizing and organizing in multiple directions to build a horizon of possibilities that moves past marriage rights: a task demanding that we fight beyond the reductive identity-based approach that sees inclusion as its primary aim. It demands that we imagine seeking justice on our own terms, via alternative forms of civic engagement.

I am interested in the history of sexual and gender movements, in the way their histories are written and told, and in the pedagogical potential of mediating and producing knowledge through art projects. I am particularly interested in documenting countercultural initiatives and in facilitating discursive platforms that can enable critical conversations around matters of social justice. This issue of e-flux journal is born from the convergence of these interests. It was conceived as a continuation of a larger discursive project I have been working on that has manifested in the online and exhibition project “We Who Feel Differently,”2 and in three experimental symposia that sought to ask what is at stake in the process of the normalization of LGBTI culture.3 The symposia brought together academics, activists, artists, and theologians to reflect on the representation of sexuality in art, culture, and society at large, proposing a politics of difference and framing non-binary classifications as social opportunities rather than condemnation.

“Difference” is a way of being in the world, and as such, it represents the prospect of individual and collective empowerment and freedom. Freedom implies the sovereignty to govern oneself: being human means being beyond parameters, being without sexual or gender constraints.4 Feeling differently entails embracing sexual and gender difference politically; it means embracing our relation to ourselves, forming communities, and working individually and collaboratively to transform the conditions that oppress us. To feel differently is to feel with agency, with self-determination. This opposition to the mainstream rhetoric of equality resists the denial of the expansive affective and sexual potentialities that are often deemed immoral, disrespectful, and (sometimes) unlawful; it also suggests an acute attention to the battles of the sexual movements of the past, which can inform present-day activism. This shift also calls for an ethics of solidarity with the social movements of other minority communities.

Considering the unprecedented visibility that some gay and lesbian issues have gained over the last fifteen years, how can sexual and gender politics themselves be “queered”? Who is being represented, and by whom? Who is excluded in the name of LGBTI equality, and how? What practical goals would move us towards a politics of true liberation? Producing critical projects as a form of mobilization serves to reexamine the idea of progress and proposes counter narratives in which queer affects, bodies, and collectivities are unapologetically reclaimed.

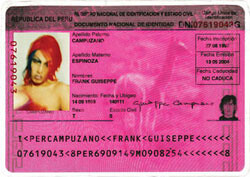

Giuseppe Campuzano, DNI (De Natura Incertus), 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

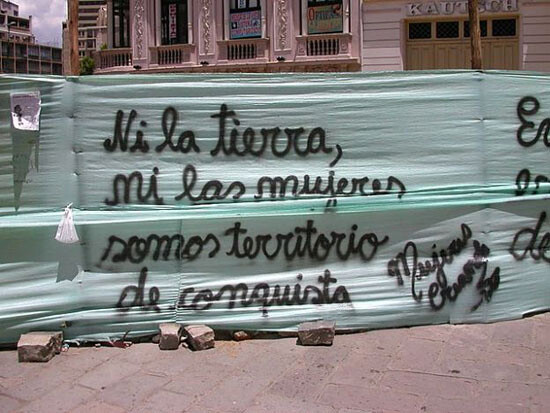

Queer art and artists have used strategies of denormalization and resistance to rupture systems of representation—to self-represent, dissent, experiment, construct fantasy, engage in social commentary, and confront power structures. Art has enabled queers to claim our place, to decolonize our bodies, to reimagine our desires, and to constitute ourselves as a political force. Breaking the tyranny of silence surrounding our experience of sexuality and gender in society has been a way of owning our presence as citizens of democracy. Think, for example, of the creative strategies used by some members of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), a grassroots movement that used “direct action,” civil disobedience, performative interventions, video art, and graphic design to confront the indifference and irresponsibility of the US government during the AIDS epidemic. ACT UP was a queer art of rage, one in which politics and aesthetics were indivisible. Or think of the transgressive project of Mujeres Creando, whose public performances, graffiti interventions, and community-building initiatives tackle the violence and discrimination inflicted upon women in Bolivia and elsewhere. Or think of David Wojnarowicz, an artist whose poetic and uncompromisingly political works challenged the normative grounds of society, from the hegemonic authority of the Church to the State’s control over bodies. Wojnarowicz’s art was a queer art of survival in which the personal was exposed as intrinsically political. Or think of Giuseppe Campuzano’s rewriting of the history of Peru from the perspective of indigenous transvestites, a project that exposes a patriarchal logic of representation and exclusion where nonconforming gender expressions are violently omitted from historical narratives. Campuzano offers a complex version of history where gender, race, and class intersect as emancipatory forces.

This issue of e-flux journal focuses on contemporary queer culture and art through ten commissioned texts by an international group of authors who reflect on present day counterculture, artistic strategies, philosophical thought, and social activism. The issue asks: Where is the feeling of queer urgency located today? And what is the role of a queer art of resistance?

Beatriz Preciado’s “Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics” explains what she calls the “pharmacopornographic” regime: a form of power that has taken over the management of life in the twenty-first century and that is structured by pornography and pharmaceutics. Preciado describes the totalizing influence this new regime has on processes of individual and collective subjectivization, in particular regarding the construction of sex and the performance of gender. Preciado tests this austere and overbearing capitalist scheme on her/his own skin by applying doses of testosterone over a long period to observe its effects and simultaneously theorize about forms of resistance to systemic control.

In “Charming for the Revolution: A Gaga Manifesto,” Jack Halberstam drafts a model of queer anarchism that rejects institutionalized forms of activism, authoritative State politics, and the assimilationist impulse of the mainstream LGBTI movement. Halberstam draws from her theory of “going Gaga” and from her work-in-progress The Wild to examine “emergent forms of life through the glimpses we catch of it in queer popular and subcultural production.”5 Halberstam’s anarchy is a critical and “impractical” project of solidarity and self-governance. It is a project that refutes the belief that radical change has been co-opted and suggests ways in which it is, and will continue, taking place.

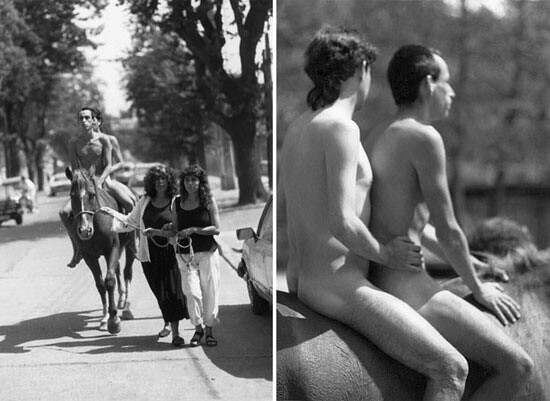

In “Queer Corpses: Grupo Chaclacayo and the Image of Death,” Miguel A. López revisits the work of Peruvian art collective Grupo Chaclacayo, active from the mid-1980s to the mid-‘90s, whose experimental political artworks remain largely underappreciated. Grupo Chaclacayo’s practice of radical sexual dissidence took place in the midst of Peru’s bloody war against the Shining Path guerrillas, a context explicitly referenced in the group’s use of the body as a social site marked by tortuous violence. López also exposes how Grupo Chaclacayo’s work responded to the Christian morality propagated by the Peruvian Catholic Church with infamous gender-variant depictions of religious mysticism and agony. The group was rejected by the art establishment and worked from the margins. López also mentions a number of other Latin American artists, placing Grupo Chaclacayo in the context of a regional cultural practice of resistance.

Virginia Solomon’s “What is Love?: Queer Subcultures and the Political Present” discusses the pioneering work of the Canadian art collective General Idea in relation to contemporary feminist and queer artists Sharon Hayes, LTTR, and Ridykeulous. Solomon suggest how the work of these artists proposes an alternative understanding of politics “in the face of governmental processes that, then as now, are either unable or unwilling to address grave social and economic injustice.” Solomon discusses the way love is invoked by these artists as an a/effective individual and collective force of self-empowerment and social critique.

Greg Youmans’s “Living on the Edge: Recent Queer Film and Video in the San Francisco Bay Area” examines the aesthetics and production strategies of queer filmmakers in the San Francisco Bay Area in relation to those of art world capitals like New York. Youmans identifies an ethos of experimentation, a resistance to professionalism, and an embracing of “failure” as radical strategies common to Bay Area artists. Youmans contextualizes his arguments by revisiting the work of The Cockettes and Barbara Hammer, who he uses as examples of marginal art practices that inextricably link the politics of sexuality and gender with the experience of building and living in community.

In “The Defiant Prose of Sarah Schulman,” Ryan Conrad, artist and cofounder of Against Equality, interviews activist, writer, and cultural critic Sarah Schulman about collaborative practice, her commitment to queer self-organization, and, in Conrad’s words, “the politics of always coming from the margins.” Schulman also shares her views on the risks of creating a biased historical narrative of ACT UP in reference to two recent documentaries about the pioneering grassroots organization.

In “A Defense of Marriage Act: Notes on the Social Performance of Queer Ambivalence,” Malik Gaines offers a critique of queer critiques of gay marriage. Sharing his personal experience as a gay-married man, Gaines challenges the radical/conservative binary often invoked by radical activists to expose how queer discourses may underestimate the benefits of legally sanctioned contracts—contracts that, in his view, can be subtly queered and disrupted on their own terms.

In “Becoming-Undetectable,” Nathan Lee identifies the construction of three phases in the history of the experience of AIDS—from outbreak, to rage, to undetectability. Lee’s tracing of these “fictions” exposes the complex ways in which the representation of AIDS, like the virus itself, has changed, but continues to (re)produce old and new forms of (representational) crises. Lee engages Tim Dean’s analysis of barebacking pornography, Leo Bersani’s psychoanalytic critique of the subculture of barebacking, and Rosi Braidotti’s ideas on “transformative projects of disappearance” to shape an unexplored ethics of becoming undetectable.

Antke Engel and Renate Lorenz’s theoretical exploration of the discourse of toxicity in “Toxic Assemblages, Queer Socialities: A Dialogue of Mutual Poisoning” suggests that the toxic may be a means to shape queer subjectivities. Structured in two voices, the text uses Renate Lorenz and Pauline Baudry’s film Toxic as a backdrop to reflect on mug shots—police photographs of “deviant” subjects—and other media technologies that intoxicate as they circulate. The authors ask, “Are there strategies of intoxication that may be turned against themselves? And could the intoxicated social body become the home of queer socialities?”

Lastly, Gregg Bordowitz’s new poem “Anhedonia” reflects on the discursive conditions and social climate of the present, expressing how they affect the voice in the poem—conditions that resonate with the themes proposed throughout these pages.

These texts draw a world of (im)practical (im)possibilities, a place where the realities we desire are not deemed impossible by institutions but instead constitute the drive to transform systematized oppression. The different authors featured here engage with forms of queerness defined by processes of self-determination and self-representation. Insisting on achieving the “impractical” may be the only way to pierce through the tired logic of contemporary political strategy and to challenge the bio-cultural and moral foundations of mainstream society. These texts, the political projects they outline, the artworks they discuss, and the ideas they set forth call for autonomous thinking in the face of a dangerous tendency to conform to restricted political, social, legal, and cultural models. They invite us to work against neoliberal paradigms of individual and collective institutionalization, privatization, and normalization.

Welcome the impractical! Undertake the impossible!6

We don’t seek equality, we seek justice.7

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to the e-flux journal team of Mike Andrews, Julieta Aranda, Mariana Silva, Anton Vidokle, and Brian Kuan Wood; Stuart Comer; Ryan Conrad; Electra’s Fatima Hellberg and Irene Revell; Cristina Motta; Raegan Truax; and the authors of the texts.

I am indebted to Ryan Conrad, with whom I discussed gay marriage from an economic perspective. His ideas have helped me shape this argument.

“We Who Feel Differently: A Symposium” was organized with Raegan Truax at the New Museum, May 3–4, 2012, see →. “Gender Talents: A Special Address” was organized with Electra at Tate Modern, February 2, 2013, see →. “Godfull: Shape Shifting God as Queer” was convened with Jared Gilbert at The Institute for Art, Religion and Social Justice at Union Theological Seminary, New York City, April 12, 2013, see →.

Carlos Motta and Cristina Motta, We Who Feel Differently (Bergen: Ctrl + Z Publishing, 2011), 11.

From an earlier, unpublished draft of the text.

Dean Spade, lawyer, activist, and founder of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, has also invoked the need to demand the impossible as a way of asserting spaces and identities “deemed impossible” by the existing system. His book Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics and the Limits of the Law (South End Press, 2011) and his recent video “Impossibility Now!” (with Basil Shadid), first screened during the symposium “Gender Talents: A Special Address,” thoughtfully articulate a nonconforming critical queer and trans politic.

Parts of this text were presented as introductory remarks during the above-mentioned symposia “We Who Feel Differently: A Symposium” and “Gender Talents: A Special Address.”