The following conversation is excerpted from FREEZONE, a discussion organized by Shumon Basar and H.G. Masters for the Global Art Forum in Dubai, March 2013. Featuring commissioned projects and research, as well as six days of live talks, the Global Art Forum brought together artists, curators, musicians, strategists, thinkers and writers under the theme of “It Means This.” Words and terms known and unknown were scrutinized or invented as a way of gauging the relationship between reality and language.

The international participants in this discussion—Turi Munthe, founder of Demotix, an English-French-Swedish online crowd-sourced news platform, Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, an Emirati professor of political science, Manal al-Dowayan, a Saudi artist, and Parag Khanna, an Indian American writer—took on the complex politics of free zones.

On November 9, 2013, the Chinese Communist Party’s central committee met to set out “unprecedented” reforms, what the state news agency Xinhua described as being “expected to steer the country into an historic turning point.” One of the most significant turning points in China’s shift from command to state capitalist economy was in 1980, when the country’s first special economic zone opened in Shenzhen. Deng Xiaoping moved China onto its market economy route by bestowing upon Shenzhen exceptional trade benefits that, in the space of a few decades, saw that city turn into the “world’s workshop.” At the same time, in Dubai, Jebel Ali Port opened, and inaugurated the spirit of the modern free zone. It is now the world’s largest man-made harbor and strategic global transport hub.

Both China and Dubai share a belief in the stimulating seduction of free zones, governed under robust State or royal power, respectively. China now exports its sovereignty to parts of Africa while buying America’s sovereignty in the form of its national debt. Dubai possesses more free zones than anywhere else in the Middle East, including its “Humanitarian City,” “Media City” and “Internet City.” But what are the long term consequences of this freedom-granting process? What does it mean to cede laws that, in Dubai’s case, have evolved into social exception zones and not just economic ones? At what point does the “freedom” embedded in the “free zone” tip, like the doomed Costa Concordia ship, onto its side? The following spirited discussion — the first part of which took place in Doha with Keller Easterling and Tarik Yousef — highlights the pleasures and the paradoxes of twenty-first century free zoning.

—Shumon Basar & H.G. Masters

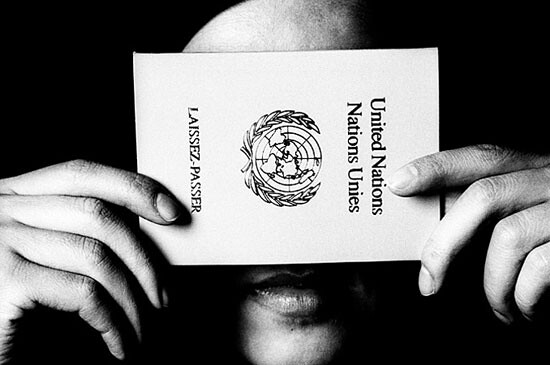

Turi Munthe: Back in the 1970s, the UN promoted free zones as these jump leads for economic growth, especially in the developing world. They were like floral nurseries; the idea was to grow the bulb in a greenhouse, and then plant it in the home soil, as a burgeoning tree. As these free zones—which were once considered temporary, immediate solutions to temporary problems—become more permanent, these big organizations are getting nervous about them. The OECD called free zones “sub-optimal” economic catalysts. Halliburton, recipient of billions of US taxpayers dollars, recently left Houston and settled in Dubai, where it can avoid paying US taxes. In that way, free zones seem particularly expensive to all but some of the parastatal organizations, which they were designed to help grow. They’re also proliferating very quickly. Can you tell us, over the course of the next ten, twenty, fifty years, as we see free zones proliferating, what their tensions are going to be, and perhaps what the future looks like?

Parag Khanna: Let’s start with the two examples you gave. Yes, the UN and various development agencies did promote free zones as a way to help initiate regulatory reform in postcolonial countries and economies that were structurally weak, and that remain structurally weak to this day. It was seen as temporary. These things have gone in waves, as you noted. Parastatal entities that are quasi-governmental but use private investment and are co-managed—this sort of thing has been around for hundreds of years. The extraterritorial zones that were part of what sparked the Opium War were parastatals, in some ways.

You gave the examples of the UN and Halliburton. Those are two completely different kinds of things. What Halliburton does is regulatory tax arbitrage. Companies do that all the time. Corporations have mobility. Most people in the world don’t. Countries and governments, by definition, don’t have mobility. Corporations, by contrast, are agile actors, so they will always practice this kind of arbitrage. They will move and shift and relocate, and adjust supply chains to find either the lowest price, or the most relaxed standards. Sometimes, however, they look for the best standards. There’s a lot of research that shows that corporations aren’t just looking to locate operations in places with the cheapest labor or the lowest taxes. They’re actually looking for skilled workers, which are often very hard to find. So what you find in these free zones—let me put one positive spin on it—is education. What you find in places like Saudi Aramco City are educational institutions that may have a higher standard.

Let’s not take an example of what is, per capita, a wealthy country. Let’s look at sub-Saharan Africa. Let’s look at the Andean region of South America. Let’s look at Central Asia. The supply chain—the corporate-public-private presence inside a special economic zone—is where people get health care and education. A Coca-Cola bottling plant in South Africa is a good example. It’s where workers and their families get HIV treatment. In mining towns in the Andean Mountains in Peru and Ecuador, companies provide schooling for illiterate people. Supply chains take these free zones into places where governance has never really stretched.

I’m giving you both sides of the story. The answer, therefore, depends on where a given free zone is and what it’s doing. But we don’t live in a world in which global governance has that capacity, that power, to set the terms, to set the standards and enforce them. It’s done within the context of these supply chains, these free zones.

But if you work on rehabilitation and, for example, provide some decent fishing boats to a local population—and this has already been done on a small scale in parts of Somalia—they will engage in fishing again, in a more competitive way than when they have to compete against South Korean trawlers that steal all their fish. In other words, Somalians don’t have some innate desire to become pirates, some genetic mutation that the rest of us don’t have. The economic opportunity has, in quite a few cases, been robbed from them. Restoring that dignity of economic opportunity—restoring a legal, exclusive economic zone—is admittedly a partial solution in which we are investing far less money than we are in forty-two navies patrolling the seas.

Turi Munthe: The tension between the state and private enterprise is as old as time. The free zone, whether it’s Venice or earlier, has existed for a very long time. But I think what’s particularly interesting here is its place-ness, its geographic location. There are certain key places which are more propitious for economic zones, and others which will have different kinds of impact. Manal, I thought your story was fascinating. You described yourself, or you described others describing you, as either a Saudi girl in a compound, or a compound girl in Saudi. Place is absolutely fundamental to this.

Manal Al Dowayan: Throughout the years, until this day, I have lived in the compound permanently. My family, my siblings all work in oil. I worked in oil. Weaving in and out of the compound is my lifestyle. I don’t know anything else. I know how to live that double life where within the compound I don’t wear a veil. I drive. There are movie theaters. I play baseball and participate in American holidays. The inside of the compound was built as a replica of Houston, Texas, or California, so that the oilmen from America would feel at home. This is my home. I don’t know any other.

When you leave the compound, it’s completely different. I wear a veil, and have to have a driver to drive me around. My friends wear veils. Types of entertainment are very different outside the compound. As for the issue of physically moving out of the compound—I haven’t done this yet, but my sisters have. They both married non-Aramcons. That’s what we call people who do not work at Aramco. I don’t know why they did it, but they did [laughs]. They left the compound. Once you marry a non-Aramcon, and you’re not an employee, you have zero access to the facilities within the compound. The doctors who treated you from the day you were born, the dentists, the school, even the supermarket—you do not have access to any of this.

There’s this huge withdrawal syndrome they go through, accommodating to daily life outside. It’s quite weird. It’s not about a place. It’s actually that Aramcons have a culture within the community. Our speed limit inside the compound is forty. Once you step outside the compound, you go crazy. There aren’t any driving rules. The way kids play, the way you eat, the way you go to a picnic and clean up after yourself, it’s all different inside the compound. If you step out into the surrounding culture, then you have this whole new negotiation with yourself. You think, maybe I need to cool down. I need to relax in relation to rules. Maybe I’m the strange one, and they’re normal because they’re the majority and I’m the minority. That’s the game that you play.

Turi Munthe: I’m struck by the parallels between what you describe and the relation to citizenship in many of the countries in this region, which comes with enormous, extraordinary, incomparable benefits for those who come here for work and define themselves by a very clear set of rules, which come with penalties. Tarik Yousef talked broadly in favor of a moderated form of the free zone. But one of his questions was, can a free zone-based city ever become a great city? Or does a city that aspires to greatness have to let in what we in Doha ended up describing as “the real”? I’ll give you an example. Xinjang’s gigantic special economic zone, which is twenty-five years old, has gotten realer and realer over the last few years as civic activism has started taking shape there. Abdulkhaleq, can you build a great city out of these very ruly pockets?

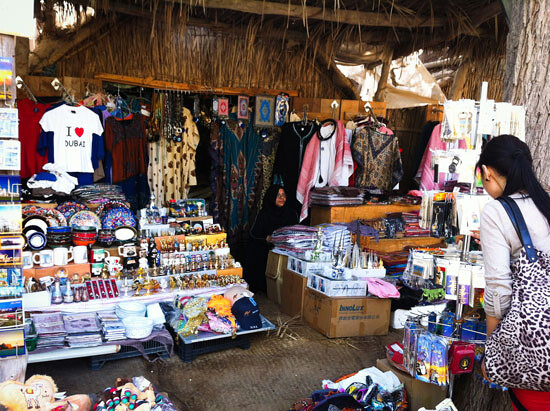

Dr. Abdulkhaleq Abdulla: Free zones are one of this city’s many icons. Dubai and free zones are synonymous. If you take away free zones, there will probably be no Dubai. And if you take Dubai away, you will not see such glamorous, elegant, state-of-the-art business. Each one has contributed positively to the other. There are more free zones in Dubai than there are free zones in the entire Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states of Saudi Arabia, Oman, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Bahrain. There are three times as many free zones in Dubai than in all of the GCC states. Thirty percent of all free zones in all of the Arab countries are located in the UAE. There are something like 150 different free zones throughout the Arab world, and forty-nine of them are located here in Dubai. The oldest, the busiest, the fastest-growing free zones in the world are here. Dubai has probably the most diversified free zone anywhere in the world. Free zones are such an essential aspect of business and of Dubai overall that they’re just indispensable to Dubai.

Turi Munthe: Free zones are defined as extrastatal spaces which have extremely precise, often quite limited rules, designed to foster very specific things. I know that Dubai has a media city, which is built around a kind of free speech that otherwise is not achieved elsewhere. It has an international humanitarian city, which, I think, hasn’t really worked. It was designed as its own special enclave. Do all these free zones end up looking like Frankenstein’s monster, not really truly organic, not really real? However much you aggregate them, will they still function as in-between spaces, devoid of this thing which is real?

Parag Khanna: It’s always easiest to explain by example, and we have two fantastic examples. One is Hong Kong, the other is Singapore. Hong Kong has in many ways influenced the way the Chinese think about capitalism. It was run by the British for centuries and absorbed into China in 1997. It’s no longer a free zone per se. It’s no longer an exclusive British entrepôt. It’s now part of Chinese sovereign territory. The range of dimensions in which Hong Kong has autonomy from China is gradually diminishing as it becomes more and more a part of China. They have unique passports, a unique currency in Hong Kong, but gradually, all these things are going to be absorbed by China.

Singapore was founded two hundred years ago, in 1819. When the territory was marked, Sir Raffles said, we are not interested in territorial aggrandizement. We’re only interested in trade. It was just a trade entrepôt for Britain. Today, it’s a full-fledged country. It has an identity. It’s actually one of the wealthiest countries in the world. It’s probably the most successful postcolonial country in the world. But it’s run like a parastatal corporation—that’s very much what it is. I just moved there a few months ago. The people realize what it is they’re living in. It’s a corporate, civic compact. It’s interesting to observe the social dynamics.

You talked about immigration. The demographics of the UAE—correct me if I’m wrong, Dr. Abdulla—are as lopsided as any place in the entire world, in terms of the indigenous population versus the foreign population. About one out of every ten people in the UAE is an Emirati. In Singapore, they’re very concerned that by the year 2030, the population will be less than 50 percent indigenous. So citizenship is no longer as relevant a concept. How do you build a sense of allegiance amongst people who have decided to permanently be somewhere that’s thought of as a transient free zone? What we need is not citizenship but stakeholdership, because people are going to permanently live in Dubai who aren’t Emiratis. And they’re going to live in the UAE. They’re going to live in Abu Dhabi and elsewhere. What is this new code or contract within the context of a free zone that makes people feel like they belong, like they have obligations, even though citizenship will never ever be conferred on them?

Turi Munthe: I think there is something very particular about that lack of long-term commitment to a historical story, a story of the future, which has historically involved the notion of citizenship, of engagement in the politics of the country in which you live. What strikes me about the Gulf is, one, the extraordinary demographic imbalance, and two, within that demographic imbalance, those people who stay here, like Manal in her Aramco compound. Manal, do you feel you’ve missed that capacity to engage with the very fiber, the meat, the body politic? I ask because this has an impact on the stakeholders in all these free zones. Are they really, fully real people? Are they really, fully engaged?

Manal Al Dowayan: I’ll speak about people in general, and then about me personally. Personally, I sort of jump into things aggressively, trying to get involved in everything. I see the potential of what I can do within a certain realm where I’m free and the rules are very different, versus the realm that I have to play in, which is more restricted. So it’s very clear to me. Sometimes it’s too clear to see things as opposites. Other citizens that live within my community are foreigners. These people also live in a bubble that’s not connected to the world they belong in. I was Creative Director at Saudi Aramco for many years. An elderly Aramcon from Texas, US, worked there too. His name was Stan. He told me that he had retired twice. He somehow managed to come back as a contractor to work in Saudi Arabia. Why would he come back? It’s because he was so in love with the country. What did he do in the country he loved so much? Not much. He just hung out, went camping—it became a lifestyle. He passed by my office to tell me this, and showed me a water bottle that was filled with sand. He said, I’m taking this sand with me to America, because when I die, I want them to sprinkle this sand on my grave. It blows my mind, this connection to a place that does not even really belong to you. And you don’t belong to it.

Turi Munthe: That belonging question is exactly what I was trying to get to. Abdulkhaleq, what do Emiratis think of the rights and responsibilities of belonging? Let’s start with rights of long-term residents of the Emirates. Their rights not just to health and safety, but their political rights. Do you think this issue of belonging should forever be tied to blood?

Dr. Abdulkhaleq Abdulla: I think you just said it. We are the Emiratis in the United Arab Emirates. We are the 10 percent. We are the disappearing minority in our own country. If there is one breach of human rights, it is the right of being a majority in your own country. When you tell me that long-term residents should be given rights here and there, this comes as a complete shock.

Turi Munthe: I didn’t tell you. I asked you what your sense was of the rights that could be conferred, or maybe have been conferred.

Dr. Abdulkhaleq Abdulla: I understood your question. Let me answer it in my own way. What I’m saying is that we, as Emiratis, have not fully enjoyed political rights yet. We do not have the right to elections. We have appointed authorities. So, for non-Emiratis to talk about political rights and citizenship just does not make sense because the contractors—they come here as guests. They come here as temporary workers. They come here to enjoy the safety of the place. They come here to enjoy the bounty. And that’s as much as they should be asking for. Do not rock the boat.

Turi Munthe: How much do artists lose, and how much does the state lose, by reducing interests down to this very small Venn diagram? Do you not gain by having the rich and the poor on the same streets? Do you not gain by having driving entrepreneurship on the one hand, and the beginnings of the welfare state on the other? I say this as an entrepreneur who set up my business in London because they had fantastic tax rates for entrepreneurs.

Parag Khanna: I think the question that’s being posed to you both is, does it have to be non-integrated? Can you imagine a world in which Saudi Aramco and Saudi …

Turi Munthe: Do you lose by not being part of a much more varied community?

Manal Al Dowayan: Definitely. There is some kind of negativity produced by being segregated into pockets. But for me, the experience of, first of all, growing up in a pocket that was privileged—not wealthy, but privileged in education and healthcare—was a very positive thing. Spreading this over to the rest of the country was something that the company was doing anyway. And it did develop the whole country. So that’s not the issue. I think Dubai has now become an incubator of young talent within the region. Talented young people are migrating here. They feel that this is the space where they can expand. This is true for me as an artist, too. Other artists from around the Arab world and Iran live here because there’s a space where we can actually think. Our existence here is respected and treated with interest and encouragement. Because this does not exist anywhere else in the region, I am totally for creating spaces that are restricted in order to not disturb this perfect equation. Let the youth come here and join think tanks. Do research. Make art. And be entrepreneurs.

Dr. Abdulkhaleq Abdulla: I think Dubai ticks because it has a huge pool of creative minds that come from all over the region—from Asia and elsewhere. It is that creative class which keeps the buzz in Dubai, and which keeps the city alive over time. The beauty of Dubai is that it doesn’t keep them for life. Once they get the Dubai training and experience, it ships them back to where they come from, whether to Syria, to Egypt, or elsewhere. They take the spirit of Dubai and the know-how of Dubai. In that sense, Dubai has not been simply a magnet that attracts young, creative, talented minds, but actually has been a net flow of creative minds. So, Dubai is encouraging this—not brain drain, but brain cupellation within the region. Some of the best Arab minds in Canada, the US, and Europe come to Dubai. The expats experience its different free zones, its different institutions, and once they feel comfortable and mature enough, they go back to Lebanon, to Syria, and so forth. They impart all their knowledge. In that sense, Dubai has served the region in multiple ways other than simply just attracting entrepreneurs who make money and go. It’s really a place that is full of creative minds from all over the place. And then Dubai encourages them to go back.

Turi Munthe: Parag, is the Dubai model helping to proliferate a polity in which you swap limited rights for the bliss of limited responsibilities?

Parag Khanna: It doesn’t have to be that tradeoff. Professor Abdulla talked about foreigners coming and demanding rights. I actually never used the word “rights” when I talked about stakeholdership. I was talking about obligations. If you are going to be somewhere and commit to being somewhere for a long time, what are your obligations to give back to that society? I wasn’t talking about coming and demanding rights at all. I was saying that foreigners shouldn’t act as if they’re so aloof to the place. If they’re going to be there for a long time, they should be asking themselves what they owe to the country, because they have to owe something to some place. They have lost their allegiance, maybe, to where they come from. But can this limited compact be sustained? Yes, if that’s what the compact is. But free zones don’t necessarily have to be non-democratic, or anti-democratic, or monarchical. They come in all different shapes and sizes. As I said, they could be corporate supply chain-type places, like Aramco City. They could be places that are democratizing, gradually, like Singapore.

Turi Munthe: Are there any questions from the audience?

Audience Member: My question is for Professor Abdulla. I belong to the part of the room that was quite chilled by some of your comments. I’m an immigrant to the United States, not by will, because I was a child. I was naturalized much later. I grew up with a lot of discrimination, specifically white supremacy. I was given the idea that immigrants contaminate the majority. In the Israel-Palestine conflict, Palestinians are disenfranchised even though they are the majority. The Palestinian womb is seen as a demographic threat. My question for you is whether or not you are endorsing some kind of ethnic supremacy. I’d like to know what you’re endorsing exactly, and what thesis you’re putting forward.

Dr. Abdulkhaleq Abdulla: I’m trying to reflect the agony of the minority in their own country, which you and many others here probably don’t go through. For the UAE citizen to live it every single day is a psychological torment that probably has not been expressed very well. It has absolutely nothing to do with supremacy, Zionism, or Americanism. Don’t just mix things together here, okay? To feel like a minority in your own country—I don’t know if you have ever experienced that. I don’t know if any nation, any nationality has ever experienced it, because we are the only country that has less than 50 percent and less than 10 percent in our own country. The percentages decrease every year. There is a possibility that we, as a UAE citizens, will be 1 percent in our own country by 2020. And probably zero percent come 2025. If that does not frighten you, you just don’t understand the feeling.

When I hear from our friends and our experts that some are starting to call for political rights and citizenship, that just adds to the problem that we go through. We should not have been put through this experience. We should not have been put into a status where we are only 10 percent in our own country. If you go to Europe, if you go to Britain, if you go to the most tolerant country in the world, where the expats, or the foreigners, are only 8 percent, hell is being raised. The government is being brought down. The prime minister is being assassinated.

This is in the most civilized, the most tolerant country on earth. So for you to come in here and tell me that I am talking about supremacy—you are not in the same position. Maybe that explains a little bit better where I’m coming from. We are here to talk about free zones. This is definitely not the topic for the discussion in this session, because it’s becoming very sensitive. If there is any other question that has to do with the topic of this session, I would appreciate it more.

Turi Munthe: My sense is that that question was very much part of the general discussion about free zones, because I think that was very directly about what is in and what is out. But are there any other questions?

Audience: Thank you for a very enticing talk. I like the concept of ferrymen and women, instead of urban nomads or bridge builders. I feel that one really important aspect of living in this free zone is the aspect of language. What kind of language do you bring, as a common language? I’m from the Netherlands, and what I see—and I think Abdulkhaleq is right—the Netherlands used to be a very tolerant country. We have a very specific issue at the moment with people who are coming in. Maybe the Netherlands is not a free zone, but it used to be a free zone of tolerance. But now, people not speaking the language of the land are creating a problem for the majority of the people. There are ferrymen going from one shore to the other in a positive way, but not being able to speak the language of the land, or not willing to speak the language of the land, because they don’t want to lose where they come from. That might be creating problems in the free zone.

Manal Al Dowayan: Language, being able to communicate, is a very, very important tool for belonging. This is something that I always go back to in my work—belonging to a space, a landscape, a community, or a political setting. Where I grew up, because there was a community of multinationals, we were forced to choose a common language, which became English. Thankfully, I had the opportunity to study both in Arabic schools and English schools. But I have cousins who went to English schools throughout their lives. Some of my father’s friends had the same experience. For them, surviving within the Arabic realm is very, very difficult. I think everybody has a responsibility to learn the language of the place they are in. It bothers me when I meet somebody that’s lived in Saudi Arabia for thirty-five years and does not speak a single word of Arabic, who has never gone into the house of a Saudi family. Although they do not see it as a loss, I think it’s a loss for them. How could you live in a country for almost a lifetime and not have the experience of engaging with the local community, not understanding their concerns? Picking up the language is a way of saying, I care. I want to belong, or at least belong in a sentimental way.

Turi Munthe: Parag, perhaps you’d like to jump in there. The ferryman, as an idea, as opposed to the global nomad or the bridge builder.

Parag Khanna: I think learning the local language is a responsibility and an obligation, maybe part of what I’m calling stakeholdership, which is vague. Manal, you’ve made it very concrete. I completely endorse what you just said.

Audience: My question is for Manal. You mentioned your sisters, who married and went outside the nest, or outside the compound. From your point of view, how did they feel afterwards? Were they offended that they couldn’t get access again?

Manal Al Dowayan: So you want a finale to the story, basically. They lived happily ever after, I guess. But when you belong to a group of friends, and you are forced to leave this group, and they decide to remove all your privileges as a friend, it’s a betrayal. And there is sadness. And there are very negative feelings. Thankfully, they have loving husbands. They left that space and moved into another wonderful space. That’s why I say they live happily ever after.

Audience: Clearly, the free zones in Dubai have helped expand the economy very quickly. But is it sustainable, politically and economically? On the political side, the free zones have aggravated the demographic imbalance that we talked about. Economically, one could argue that the free zones of homeownership helped create the real estate crash of 2008. Will this dependence on free zones serve Dubai’s long-term interests?

Dr. Abdulkhaleq Abdulla: It has already served Dubai hugely. The question of sustainability always comes up with the Dubai model, which a lot of people doubt. How sustainable is the Dubai model? Dubai has proven time and again that this is a sustainable model for two reasons. One, you had the crash of 2008. It was a very difficult time. People said, this is the end of Dubai. This is the end of the Dubai model, the Dubai dream. But Dubai is back now. It’s up and running. Hence, I think the way it managed to handle that crisis has proven, beyond a doubt, that this model has its own weaknesses and its own problems, but at the end of the day, it is sustainable. The strategy behind Dubai, and hence the free zones, is to build the first post-oil economy in the oil region, and to make sure it is successful and sustainable—to make sure it performs even better than the oil economies. Oil now contributes only 6 or 7 percent to GDP. Dubai lives in an oil region, but it does not depend on oil directly.