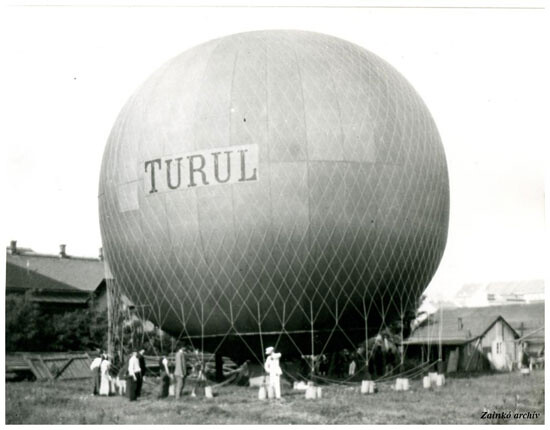

The powerful reappearance of the Turul bird in Hungary has become one of the key signifiers of the new national self-definition of the country’s right and far right. The symbol is rooted in mystical and romantic historiography, which are the main tools for constructing the current national identity and its historical mission in Europe and the world.

According to researchers, the cult of the Turul is based on the totemistic relationship between the nomadic Hungarian tribes and the Saker Falcon, a hunting bird of the Central Asian steppe. The Turul as a symbol is present in two main narratives from ancient Hungarian legend. The first is “Emese’s Dream,” in which the progenitress of the Hungarian people is impregnated by a Turul and gives birth to the Árpád Clan, which ruled Hungary during the country’s golden age, from the tenth to the thirteen century CE.1 The second narrative is “The Conquest of the Magyars” (“Honfoglalás”), which concerns the territorial legitimation of the Hungarian state. In this story, Turuls led a group of wandering tribes into the Carpathian basin, showing them the land of their future country.

The Symbolic and the Legal

In 2004, the Hungarian parliament passed a resolution affirming the national symbolic value of many animal breeds native to Hungary.2 Although the Saker Falcon isn’t among the more than one hundred species traditionally bred by Hungarians, in 2006 its temporary replacement on one side of the fifty forint coin by a different design generated anger on the far right, even though this depiction didn’t resemble the historic icon of the Turul. “Turul” was also briefly considered as a possible name for a new Hungarian currency introduced in 1926 (authorities ultimately chose the name “pengő”).3 Ironically, it was an EU-supported LIFE grant that led to the successful resettlement of the species in the region between 2006 and 2010.4 In 2013, a bill introduced into the Hungarian parliament by seven MPs of the radical right Jobbik party would have imposed a one-year prison sentence on anyone caught defacing images of the Turul or the Miraculous Deer, another important figure in the Hungarian ethnogenetic myth.5 Although the bill did not pass, if it were reintroduced today, it might pass easily, as Jobbik itself has presided over the new parliament’s cultural committee since April 2014.

The story of a memorial depicting a Turul that was erected in the 12th district of Budapest in 2008 is symptomatic of the changing symbolism of the Turul. The board entitled to decide upon the issue ruled against the construction of the memorial. In spite of this, the local mayor, a member of the conservative Fidesz party, green-lighted the project.6 As Gábor Demszky, a well-known liberal politician, noted, “The Turul … became the symbol of unauthorized construction and of official authority that disregards its own rules.”7 Thus, the populist ethos of the “freedom fighter” was implicitly introduced. This later became the main metaphor of Viktor Orbán’s “rebellious” relationship to EU norms and standards: in defense of the new national self, the authoritarian handling of laws is acceptable.

Following the methodology of the British anthropologist V. W. Turner, the polysemous character and multivocality of the Turul symbol can be analyzed with a triarchic approach, involving an exegetical, a positional, and an operational interpretation.8 The exegetical interpretation relates to ritualistic behavior (totemism, shamanism, paganism). The positional interpretation relates to the symbol’s iconological context (revisionist and nationalist elements, such as Greater Hungary, Árpád stripes, and the arrow cross). The operational interpretation concerns what is done with the symbol in public rituals, political rhetoric, trendsetting fashion, and so on.

The Turul and the Pre- and Posthistoriographical Fields (Exegetical)

The current interpretations and political instrumentalizations of the Turul symbol connect to three main historical perspectives: prehistorical, historical, and posthistorical. Pre- and posthistorical perspectives are used by popular, esoteric-mystical historiography. Official rhetoric shifts between these and the main historical argument, namely, that the Turul symbol was used by the honorable Árpád Dynasty. This argument is used to legitimate the symbol and purify it of the racist and fascist connotations it gained in the twentieth century. This contradiction fuels the controversy around the symbol’s various usages, ranging from official to subcultural, from national to extremist.

The prehistorical perspective positions itself in mythical times, before the settlement of the Hungarians in the ninth century CE. It goes back hundreds of thousands of years, to the era of occult religions. The Arvisuras, a pseudo-historical literary work describing elements of the “táltos” tradition (the Hungarian shamanic tradition), provides a framework for the occultism of some of the far right groups and subcultures which often cite this narrative as a source.9 Some of these groups identify themselves as spiritual UFO hunters and claim that in the year 12788 BCE, the Turul Clan left the planet Turul in the solar system Sirius B and landed on earth.10

The content of Arvisuras is highly speculative and controversial. One of the conspiracy theories around it states that the mythological prehistory it describes was manipulated by Stalin’s counter-information service with the intent of depriving Central European nations of their true history and identity by creating a nonhistorical, phantasy-based ethnogenetic narrative.11 This interpretation clearly integrates anticommunist elements, which are an important part of the rhetoric of both the center-right and the far right.

The posthistorical perspective relates to the period that started with the Trianon Peace Treaty (1920), when, as an effect of postwar trauma, historical consciousness began to step out of reality. In 1919, the Turul Association was formed from several other Christian-nationalist comrade-in-arms groups. Starting in 1928, they held regular, aggressively anti-Semitic demonstrations, and eventually boasted a membership of over forty thousand. Gyula Gömbös, who was prime minister of Hungary from 1932 to 1936, was a central figure and honorary member of the association. He spread protofascist ideology based on the Szeged Idea, a notion developed by anticommunists in Szeged, Hungary in 1919 that blamed a “Judeo-Bolshevik” conspiracy for Hungary’s defeat in WWI.13 After WWII, authorities banned the Turul Association, but András Siklósi, an anti-Semitic poet from Szeged, claims to have recently reestablished it.

Ideology and Fashion (Positional)

Since 1989, the Turul symbol has gradually appeared in various popular designs, from T-shirts and flags to wall clocks, bags, wine, and cutlery. While the iconology of the designs was based mostly on the interwar national-romantic representation of the Turul, starting in 2010, as its usage spread significantly, a new style appeared. This style used the visual language of Kalocsai and Matyó, two folk traditions of the 1920s, an era when many producers and trade groups, such as the National Federation of Women Tailors, began mass-producing folk-style clothing. In 1934, the Committee of the National Movement for Hungarian Clothing was established to promote this trend among the interwar aristocracy.

In 2010, the Hungarian government launched the Gombold újra! (Re-button it!) campaign, which called on designers to integrate, once again, traditional Hungarian folk elements into contemporary fashion.14At the same time, the number of online stores offering items with explicitly nationalist designs increased significantly.

It is worth mentioning that the Matyó folk tradition, which these designs are based on, was added to the UNESCO list of representative cultural traditions in December 2012, on the initiative of Hungary.15 Coincidentally, during the same UNESCO session, falconry—a sport and hunting method that is deeply rooted in Hungarian history—was also added to the list.

Public Rituals in Culture and Subculture (Operational)

The symbol of the Turul has been used in various ways throughout history, mostly in a military context; even now it is used in the logos of three major Hungarian institutions: the Military National Security Service, the Hungarian Army, and the Constitution Protection Office, as well as in a number of official seals of Hungarian settlements. But following the Trianon Peace Treaty, its meaning underwent a significant transformation: it became the general symbol of “national resurrection.” The Treaty resulted in the loss of about two-thirds of Hungary’s former territories and population. This was experienced as a sociohistorical trauma, and led to an explosion in revisionist politics during the interwar period. Thus, the Turul was gradually transformed into the symbol of the effort to reconquer these lost territories, which ultimately drove Hungary into the catastrophe of WWII.

Due to its fascist-revisionist references, the Turul was tacitly banned from Communist iconography, only to reappear in the public realm after 1989, mostly in popular culture. In the last decade, many new monuments depicting the Turul have been installed, especially since 2010, as a result of the official memory politics imposed by the Fidesz party. There are now more than 257 Turul monuments and statues across Hungary and in neighboring countries, some of which were erected even before WWI and the interwar period.16

In 2012, a ten-meter high Turul monument was erected in Ópusztaszer National Heritage Park. Its unveiling was presided over by Hungary’s current prime minister, Viktor Orbán, who started his inaugural speech by saying: “The Turul is an archetype of the Hungarian people. We are born into it just as we are born into our language and our history. The archetype belongs to our blood and motherland.”

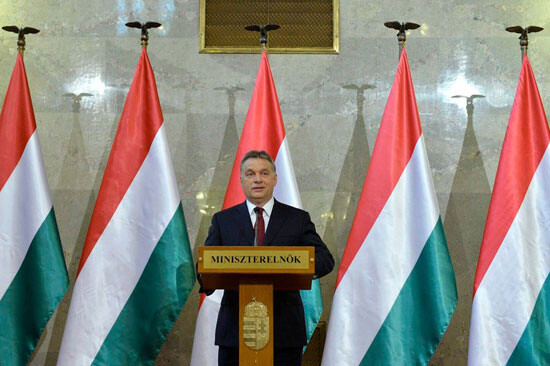

Since then, the measures taken by the Hungarian government, especially in the field of art and culture, have clearly followed the ideology of “blood and motherland.” After the elections of April 2014, in which Fidesz unexpectedly achieved a majority again, a press conference was held. On the stage at the press conference, a small but significant new element had been introduced in the background: the finials on the tops of the national flags were changed from the classical spear to the “archetype” itself.

The symbolism of birds of prey goes back to ancient Egypt. Their usage was transmitted to modern times through Imperial Rome, where they were used as finials on the military standards carried by the Roman legions. The symbol has been widely used in heraldic iconography from the Byzantine Empire to the Third Reich. One can only hope that the new Turul finials on the Hungarian flag are intended to refer to the aquilas of the Roman standards rather than to the Turul’s usage during the darkest period of Hungary’s past.

“Emese’s Dream” is one of the earliest known tales from Hungarian history. The legend can be tentatively dated to around 860–870 CE, and with certainty to between 820 and 997 CE (between the birth of Álmos and the mass acceptance of Christianity).

Parliamentary resolution 32/2004. (IV. 19.): “Protected, native, and ancient Hungarian animal species have their roles in education, the arts, and the preservation of our national identity. They represent an aesthetic value and their genome has economic significance … We consider the animal species listed in the attached document to be native and at the same time—in their names and appearance—symbols of Hungary.”

See (in Hungarian) →.

See →.

Parliamentary modifying bill nr. 2013/ T/10273. Jobbik promotes an openly anti-Roma and anti-Semitic ideology and is currently the third largest party in the National Assembly.

See →.

See (in Hungarian) →.

See →.

“Arvisuras” means “truthfulness.” The story is based on an oral myth transcribed by a simple steel worker, Zoltán Paál, in the 1950s and ’60s. According to legend, while Paál was in captivity during WWII, he was initiated by a Soviet partisan-shaman into a secret tradition. Following the war, Paál spent his years transcribing the myth, resulting in a literary work of more than ten thousand pages entitled Sealed With Blood. The work was partially published in 1972 and almost entirely published in 1998.

See (in Hungarian) →.

See (in Hungarian) →.

Gyula Gömbös is still an honorary citizen of Szeged. Local Fidesz and Jobbik MPs blocked the withdrawal of his honorary citizenship in 2011. The archive of the Turul Association was almost entirely lost during the siege of Budapest in 1944, but an interesting fact remains: starting in the mid-1930s, communist students with subversive intentions enrolled in the group, which led to a schism in 1943.

See (in Hungarian) →.

For a map showing the Turul monuments throughout the territory of prewar Greater Hungary, see →.

This text is based on a lecture given within the framework of the exhibition Like a Bird: Avian Ecologies in Contemporary Art, curated by Maja and Reuben Fowkes (Trafó Gallery, Budapest, December 2013–January 2014).