Audra Simpson: Where was When the Dogs Talked made? And why was it made? How does it relate to the earlier short film by the Karrabing Film Collective, Karrabing: Low Tide Turning?

Elizabeth Povinelli: These film projects began as something quite different than what they ended up being. I talked a little about this in an earlier e-flux journal essay. A very old group of friends and colleagues of mine were working on a digital archive project that would be based in the community where they were living. But after a communal riot, they decided being homeless was safer than staying in the community. So what began as a digital archive that would be located on a computer in a building on a community was reconceptualized as a “living archive” in which media files would be geotagged in such a way that they could be played on any GPS-enabled smart device, but only proximate to the physical site the media file was referring to. We thought this augmented-reality–based media project would have two main interfaces, one for their family and one for tourists. And they thought this would be a way of supporting their specific geontology—their way of thinking about land and being—and create a green-based business to support their families.

But they faced two obstacles as they tried to build this living library. On the one hand, the Australian economy was increasingly oriented around a mining boom, supplying raw minerals to China. This raised the value of the Australian dollar and the price of goods and services, and crippled other domestic industries such as software design and tourism. On the other hand, a sex panic was gripping the nation around the supposed rampant sexual abuse of Aboriginal children in remote communities. The federal government used the sex panic to roll back Indigenous land rights and social welfare, and to attack the value of Indigenous life-worlds more generally. So instead of making the augmented reality project, my colleagues decided that we should make a film that tries to represent and analyze the conditions in which they were working—the small, cumulative events that enable and disable their lives. They thought this would give everyone a sense of the various kinds of media objects that could eventually be in their geontological library. And I should say that they wanted to make a film with people who could show them how films such as Ten Canoes were made. That is, they had a very specific kind of film in mind, one that, at least initially, demanded a level of craft that I didn’t have.

I asked Liza if she’d come out, meet the Karrabing, workshop the story with us as a collective, and codirect our first film, Karrabing: Low Tide Turning. I had seen and heard about a number of short films she had made, especially South of Ten and In the Air, and I thought she’d be perfect for what we wanted to do. South of Ten, for instance, is able to pay cinematographic attention to the ordinary material conditions of getting by in the wake of Hurricane Katrina without making them a weird dramatic personage. In one clip you see a woman washing dishes in a large white bucket with a FEMA trailer in the background. The heat, the industrial nature of the bucket, the FEMA trailer—these are the completely non-remarkable conditions of the cast-off and getting-by. In the Air also got my attention for similar reasons. It’s set in the crumbling US rust belt, now the Meth Belt, and encounters a group of kids who have set up a circus school as a way of organizing a center to their lives. For me this film is a study of the small, non-spectacular ways people try to create projects and events that can sustain them in the midst of social and material decay. Oh, and I should say that both films work with nonprofessional actors.

Liza Johnson: Of course I knew Beth, and Beth’s work, when she invited me to do this project. I was interested to meet her friends and family. I was also interested in the intellectual intersections of the project because it seemed like a compelling opportunity to work across the discourses of art, cinema, and anthropology, which have a lot to say to one another but often fail to say it. I hope and believe that this is changing, but for a long time I have felt the very strong legacy of modernism in art contexts, a legacy that can be suspicious of documentary impulses and ethnographic research, as if these methods are dangerously unmediated, or somehow claiming to be “in reality, in truth, not in ideology.”1

And then on the flip side, in anthropology, it can seem as if only ethnography is real, and that there is no thinking done by representation—that filmmaking is just craft knowledge. I had collaborated with an anthropologist in the past, and when we finished the project he was very quick to claim mastery over the content, relegating me to the form side of the equation, as if the two could be easily separated. And as if you can have mastery over content when that content is itself a group of living people who have mastery over themselves!

Within art contexts, this split sometimes has formal implications too, most obviously between a representational paradigm that may aim to generate shifts in meaning or ideology, and a public art or relational aesthetics paradigm that may think of social relationships as the material and medium of the work. But isn’t it possible to gesture in both directions?

Cinema and theater offer a lot of models that we could aspire towards, including: Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed; the kinds of participatory projects that Jean Rouch made, and that Faye Ginsberg champions; classical and contemporary forms of neorealism; and even in the legacies of minimalism, like Akerman and Warhol, for the ways that eventfulness and the everyday are distributed. I’ve been very interested in Lauren Berlant’s project, including her characterization of the cinema of precarity, and in Ivonne Marguelies’s work on realism, and especially on the role of description in creating a kind of critical purchase on eventfulness. These references, in conversation with a set of references traditional to the Karrabing mob, were the basis of the workshop that we did with the Karrabing. Fundamentally we aspired to Boal: What are the conflicts of everyday life, and how might we act upon those conflicts if we try to act them out?

EP: Karrabing, When the Dogs Talked, and the film we’re currently making, The Waves, are interesting hybrids, mixing Boalian and Karrabing analytical techniques, neorealism and collective ethnography, representation and enactment of social worlds. But the Karrabing is also an interesting hybrid, maybe deranged, social form. The Karrabing is not a “tribal group” nor a place. Karrabing is an ecological condition—it’s the Emiyenggal word for the state when the tide has reached its lowest. Most members are from contiguous coastal regions around the Anson Bay, though from different so-called traditional lands. So the Karrabing decided to use this ecological condition as the name of its legal corporation in order to emphasize that they are a kin/friendship group rather than a local descent group, namely, the kind of social formation the state recognizes as a form of land-based ownership and decision-making. So making films that represent and analyze the conditions in which they are living is also what allows the Karrabing to make a case that the kind of social form they are should create a space in state forms of recognition—especially the domineering classical anthropological imaginary of territorially based clans and tribes.

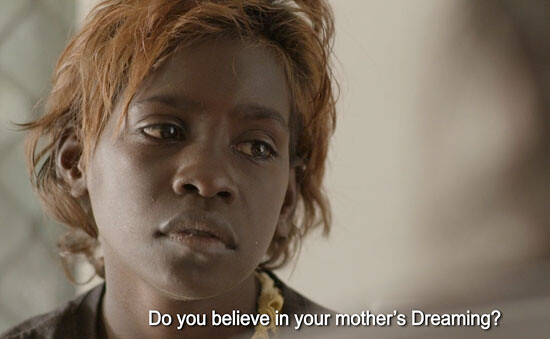

AS: Dogs seems at heart to be a critical analysis operating outside academic genres of explication. On the surface we seem to be watching a fairly straightforward plot. Low Tide Turning told the story of an extended Indigenous family who, faced with losing their public housing if they don’t find a missing relative, embark on a journey to find her, only to wind up stranded out in the bush. When the Dogs Talked incorporates this plotline but seeks to tell a slightly different story: “As their parents argue about whether to save their government housing or their sacred landscape, a group of young Indigenous kids struggle to decide how the Dreaming makes sense in their contemporary lives.” But the film stages, without being stagy, a clash between various kinds of authorities over the meaning and sense of what gets glossed in various literatures as “The Dreaming”: the ancestral world of beings who made the present geography.

On the one hand, the film is slung around the continuing presence of a Dog Dreaming—a group of dogs who once walked and talked like humans. As the Dogs traveled along, as they tried to make a fire and eat the yams, they rubbed their fingers down until they turned into paws and burnt their tongues. So today, dogs can no longer speak. Each place where they were frustrated, they made a mark on the land. So the film shows, for instance, a set of water wells that the Dogs made as they tried to make a fire. These Dreamings do much more than mark the movement from territory to place. They connect people to that place and to each other through time. These Dreamings carry with them boundaries in their stories and in their telling of the story at places.

But even here the state has another “dreaming,” and this “dreaming” would be the legal and public fantasy about what a traditional group should look and act like, how it should be composed, what people are allowed to think and say about their “traditions.” This is what you’re referring to when you say that the Karrabing do not conform to state-based modes of recognition. And we see this in Canada too, after the Van der Peet Decision—and maybe less virulently in New Zealand. We could say that the state has a dreaming of the Dreaming: a form that Indigenous and Native peoples must conform to in order to be traditional in the right way, the state way, to get back your pre-settlement rights to your land, no matter that these state-ways are not your ways. And throughout the Native world we see lives lived in a constant contortion, and it’s not a good yoga pose. It’s collectively experienced and carries great costs.

I love that the film pivots this analytics around a young Indigenous girl, Telish, and what she believes made the water wells—ancestral dogs who walked and talked like people? Or a human machine of some sort? Telish is being told the story of her mother’s dreaming and thus her mother’s land and her mother’s law, what I think we might understand as law. Does she believe this, does she think it was dogs that do this or did this, or does she think the machines did this? This is the invitation I think: to sit with Telish and wonder what to think. Because settler and Indigenous dreamings are operating in the same place among the same people and it leaves in the center of the narrative a space for doubt or skepticism. Which should I believe? Is this state or this dog story really real, is this really true, should I believe this? This space of internal skepticism about both is very generative and productive, but so subtly played. At the beginning of the film, I saw the shadow of doubt on her face. And then at the end of the film, I saw no doubt, I saw a belief, and then I saw fear.

EP: I am glad you liked that. We wanted to dramatize that the materiality and sociality of the dreamings exists here and now and thus must continually find some anchor in the actual world people live in if they are to continue existing. So the pivot of the movie is about the kids asking themselves: If we agree that the world is literally, ontologically formed one way or the other, what does that make us retrospectively? If we agree that a huge dog that walked and talked like humans made the geography, what will we be? Primitives? Uncool? Backwards? Hicks?

So the film is cut to use Telish as the person who is considering this problem. If I believe and act on the belief that dogs made these holes, does this put me in an impossible space, put me in a space between the state, pop culture, and my love for my family?

AS: And I think this is why there’s always been ethnographic austerity in your written work, Beth—in what you write about your friends and colleagues. I’m seeing this now in this film. There’s a politics in this descriptive austerity—we’re shown the richness of the ways in which these people are communicating; the way they make boundaries; and what lies beyond boundaries and then simultaneous orderings, as well as the continued life on land with others. But the analysis is focused on the ways that the ordinary everyday workings of state bureaucracy and poverty drain the resources and energy from them—and how they nevertheless keep going along.

And here is where I see another kind of dreaming authority, white man’s dreaming, by which I mean the state’s dreaming, its architecture, its bureaucracy, and its regulations, its “standards of cleanliness” and ideas about safety. In Dogs, we see and feel the effects of this imagining or coming-into-being of the settler world as it re-instantiates itself over and over again in Indigenous life through its techniques of surveillance, regulation, and the production of poverty—the overcrowding in government housing, for instance, because they have made living in rural and remote communities almost impossible.

I say “the production of poverty” because you can see so clearly at one point the profound desire and exasperation that comes with this desire and call to hunt. This call and desire to hunt needs to be set aside to chase Gigi so that she can show up at territory housing, and I guess rather ridiculously, make a case for herself in terms that such a state will understand. Which is probably not the excuse that it probably is, which is simply, she’s being a responsible family member while living in Darwin.

In terms of Indigenous life-worlds in what are called multicultural, liberal settler colonies or former colonies, there’s a terrific press for performance. It’s the performance of pure culture, it’s the performance of not having lost what you were actually supposed to lose quite fast.

EP: Yes, this is exactly what the Karrabing want to get on the table—or the screen. How both of these positions—I believe that dogs once walked and talked like we do and that they made water wells that still exist; I don’t believe … —constitute an impossible choice thrust upon them. And what kinds of efforts allow them to live the answer rather than answer the question. What I mean by this is fairly simple-minded. In making the film, in staging the kids having an argument about what might have made the water wells, the Karrabing are in fact keeping the water wells and the Dog Dreaming alive and active in their kid’s minds.

AS: Do you care about the genre of this film? It doesn’t seem to be ethnographic, it’s not documentary, but the narrative is, if I am right, lifted out of the actual lives of the Karrabing. So there’s that kind of slyness of genre in this performance. At what point does performance begin in that kind of dialogic space?

LJ: In this particular social context (and arguably in others) there isn’t really an outside to performance. When we undertook this project, the question was intensified by the federal intervention—the rollback of Indigenous rights based on a sex panic. Prior to that moment, to secure resources from the state, it was necessary to perform your (real) relationship to tradition to get control over your land. And then suddenly, on a dime, to secure resources from the state, you have to perform your relationship to assimilation.

And so that conflict, while not articulated in those terms at every moment of everyday life, does place performance demands on subjects within their social worlds. And it also bears on the representational question within the film. I like how Audra is talking about how that is intensified in the figure of Telish, and I think a version of the same is also true for the other characters.

It raises a question about performance, one that can also be raised in other kinds of neorealism. This question has to do with what happens when there are “breaks” in performance. Do those breaks function in a Brechtian way, offering a critical distance of some kind? Or are they really even breaks, since the performing subject is also asked to perform in certain ways outside the framework of the film performance?

The story is designed collectively through a kind of workshop process. But as for the script, I don’t think there is one. Improvisation, which in all its forms—comedy, jazz, acting—really only works when you’re working off of a structure, is a really useful technique when working with nonprofessional actors. Through workshopping, everyone knows what’s going to happen and knows what the scene is and knows what they’re trying to do, but gets to say whatever they think is the right thing to say.

This is where it’s also not just representational, but an enactment on the ground in a particular context. It’s a very contingent world, which has a determining impact on the narrative decisions. But on the other hand, there is no way to overstate the ways that the obstacles of poverty and racism can limit people’s ability to do the things they want to do, and so we all had to ask ourselves, how much of a continuous story do we want to try to tell when it’s completely unclear whether the people who can appear on day one of the shoot will be structurally able to return for the second day? And in that sense, it’s radically different from industrial filmmaking, where that’s all guaranteed and bonded by an insurance company.

Which actually was an interesting enactment while shooting because—and I mean this in a very non–self-congratulatory way, and I am suspicious of people who would congratulate me or Beth on this topic. But there is a real scarcity of meaningful work, or any kind of work. And on the days when we were working, there was, and that was an interesting enactment in the space—a day of meaningful work, though sometimes boring, is a different day than a day of no work. It’s one of the relational things that is changed during the shooting.

EP: Yes. For while I was assigned the job of directing. Part of my job was allowing for constant potential rearrangements of character, dialogue, and story line. In our recent shooting of The Waves, for instance, one of the young men, Cameron, did not want to be cast as a member of the group of young men who stumble upon two cartons of beer. He wanted to be a Karrabing Land Ranger instead. His change of mind came fairly far into the story design, but because everyone thought this made sense for Cameron, my job was to help realign the story—and it didn’t have to work out this way, but it turned and deepened the story as we incorporated this new character.

AS: What has the film done? Both of you have said it was as much about constituting Karrabing as representing them.

EP: Yes, that’s right. Of course, one of the central questions is how does one shape the force, form, and direction of this constitution so that one can take advantage of certain, say, Late Liberal/neoliberal discourses of capacitation, even as what is being capacitated does not conform to the imaginaries of difference and markets within Late Liberal settler society?

LJ: I’m suspicious of certain new and powerful models, which are increasingly being used by documentary funders, of requiring documentaries to have “measurable impact.” (Meg McLagan’s work on this topic is extremely useful.) I think it’s our job as artists and intellectuals to be out in front of things, like canaries in mineshafts, and to be looking for things which are there to be sensed—like a tingling and hopefully collective Spidey-sense—but which might not yet be there to be measured. Something more like “structures of feeling,” or things that are in the air, which might have some other kind of impact, some immeasurable impact. Part of what we’re doing is asking, collectively, what would be our categories?

EP: I think this is the perfect place to end.

Hal Foster, Return of the Real (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 174.

Subject

This is the conclusion of a four-part meditation in this issue on the problem of time, effort, and endurance in conditions of precarity, and pragmatic efforts to embank an otherwise. All film stills are from When The Dogs Talked (2014), and Low Tide Turning (2012), films by the Karrabing Film Collective in conjunction with Liza Johnson and Elizabeth A. Povinelli. The films were written by and star members of the Karrabing Indigenous Corporation.