“In our hands they must become weapons … ”

— Harun Farocki, The Words of the Chairman, 1967.

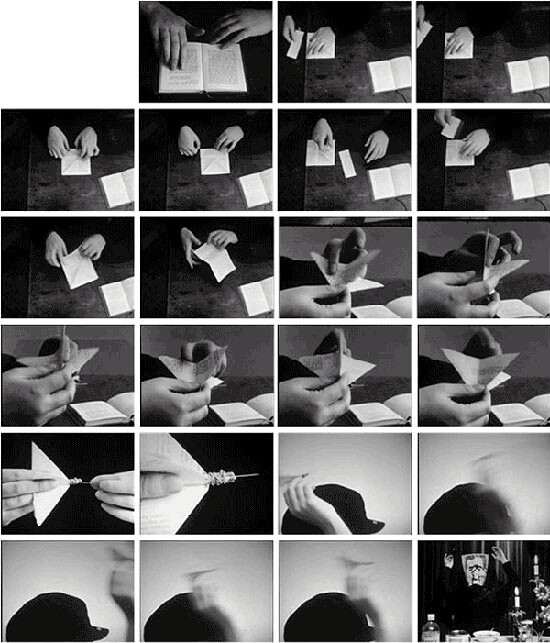

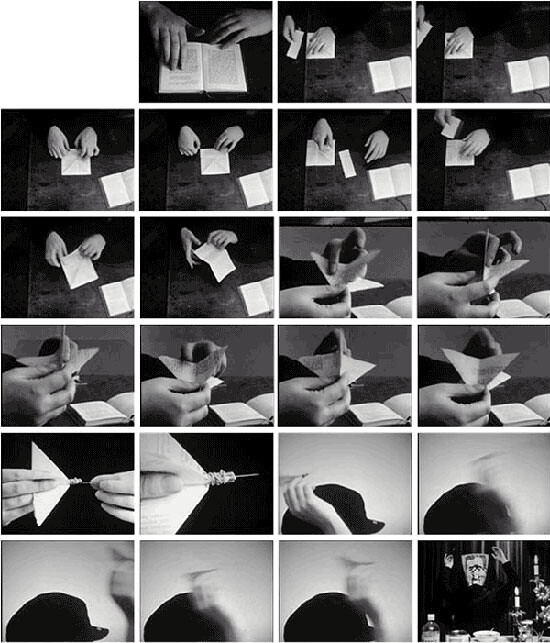

Using controlled methods, sometimes even irony, Farocki takes apart over and over again, piece by piece, our place as victim as well as culprit in this age where the image is loaded like a gun. It is a rage that is not violent, yet clearly spoken, and which is resting behind Farocki’s camera, not necessarily front and center on the screen. Demonstrating, describing, pointing out, and gesturing: his hands and his words shock, confuse, stir, and arouse us. But let us not get it wrong: it is not about what or how we are feeling, but more specifically, about how we see and how this is fabricated, and then asking ourselves “what do we do about that?”

Throughout Farocki’s work, cinema and video become looking glasses into themselves; into images and the demons set free when imbuing them with so much power. Despite the rage, there persists a retained vision—calm and confident, yet never arrogant—of the state of things. Yet, there is nothing esoteric or mysterious to it; images are powerful, and power does not hesitate to use them.

For me, this is the most humbling experience to be had through Farocki’s work, as he reminds us of our role in image making. Somewhere, he himself said that it is not what is in a picture, but what lies behind it that counts; that this should not stop us, as it never stopped Farocki, from using and showing images, as if they are the only source of proof we have for certain things.1 Georges Didi-Huberman also depicts this phenomenon in his book Images Malgré Tout (2003), which describes the context of four blurry photographs desperately smuggled out of Auschwitz-Birkenau by the Sonderkommando, the inmate Jews forced to aid with the disposal of gas chamber victims. These four photographs, however sparse, became proof of the event, though they are beyond words. No picture could ever describe nor retain the actual meaning of those atrocities, nor is the idea of proof even a valid one in this context. In the context of such violence and tragedy there should be no necessity for visual material in order to convince us, at a later date, of what took place there, but it is crucial to note that these photographs do give us, in the end, a startling glimpse into the human nature behind those actual murders, if not into the circumstances of actually capturing that moment. It is not only because of the angle from which they were taken nor the frenetic quality of the pictures, that we can confer that these people were taking a risk and making an act of resistance when they captured these images and somehow had them smuggled out of the camps. The simple idea that those inmates, although themselves faced with unavoidable extermination after being forced to participate in the disposal of the bodies of their kin, were worried about the image that could survive is remarkable. If we think again to Farocki’s idea of what lies behind the image, then we can understand image-making as not only visual document, archive, or evidence, but precisely as proof that something has been done or an act of resistance has occurred.

In his writing on prisons and his work with surveillance images, Farocki insists on how a paradoxical act of watching and documenting can become an opportunity for resistance. Describing the state of prisons today, he says that prisoners are “withdrawn from the gaze, made invisible” while each “picture from prison is a reminder of the cruel history of the criminal justice system.”2 An example is from his video installation I Thought I Was Seeing Convicts (2000), where Farocki does just this: he reminds us of the surveillance mechanisms that we have created and that are imbued with our own confusion and perplexity. The surveillance cameras allow us to engage in an exercise where we gaze at inmates who have been reduced to points and shadows on a screen, while at the same time giving us the necessary pictures that attest to our society’s cruelty. It would be unjust to compare these images to those of the Sonderkommando, but the juxtaposition reveals something about the image itself and attests, although from a different perspective, to the cruelty that we are still capable of. If we reconsider our role as those who believe we create images as “proof,” then it seems almost perverse to see how these images can be emptied of their intent to document or archive and become another dispositif in our liberal society’s self-numbing. In the case of surveillance cameras, we have relegated our active role to machines that do the work for us, thus giving us a degree of separation that ultimately protects us by allowing us to deny our responsibility in the atrocities. Taking a lesson from Farocki, maybe the only way to deal with this is to reconsider these pictures, this proof, and to show them to the world and to ourselves through repetition. In Farocki’s work, the urgency is not just about making the images, but about watching again and again, about seeing the details and thinking through these events over and over.

As we try to make meaning of this ever more chaotic and absurd modern condition, and our participation in it, it is maybe only through filmic acts that we can maintain some urgency where numbness tends to reside. Just as Didi-Huberman insists on the necessity of the image, no matter what brutality surrounds us, I believe that Farocki also lived urgently and in the moment, teaching us that if we do not make (or re-make) these pictures, then who will?

Thomas Elsaesser, “Harun Farocki: Filmmaker, Artist, Media Theorist,” Afterall 11 (Spring/Summer 2005).

Harun Farocki, “Controlling Observation,” in Harun Farocki: Working on the Sightlines, ed. Thomas Elsaesser (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004).