Corruption is the disappeared body coming back to life.

Its flesh seizes the veins of the postrevolutionary state, pumping, circulating, and blocking in a synchronized manner while unleashing shape-shifting forms as its residue.

In medieval Europe, the Sovereign’s body was considered to be double: the limited apparatus of the natural body, and a larger state of abstraction of the body politic.1 Together they formed the geocosmic “whole” of sovereign territorial governance, unifying a corpus of subjects and providing a temporal stabilizer. Mortality and exhaustion could be associated with the ruler as a human protagonist, while the more-than-human power matrices of rulership could be implanted in the mystic morphology of the kingdom or commonwealth as a higher ground. This prevailing notion of the two bodies permitted the continuity of monarchy even upon the death of the monarch, best expressed by the formulation “The King is dead, long live the King.”2

However, the deception at the heart of this circuit causes a third body to arise from the organically immunized perpetuity of the double ruler.3 And this third body does not inhabit either of these theological conceptions derived from the Christian corpus naturale and corpus mysticum. We can call this third morphology “corruption.”

Corruption literally and symbolically splices through the indivisibility of the two bodies as a corporeal passage that undermines the singular thrust of their governing power. Casting a shadow reality over the surface of society and then dynamically percolating deeper, the parasitic quest of Trojan horses, double agents, fly-by-night operators, shady middleman with multiple cell phones, and match-fixers creates a relation with a business-friendly face before lurking into the “back office” to disclose their objectives.

The missing tape, the back office, the black market, counterfeit currency, that lazy bureaucrat, the anonymous file, the phone tap or leaked SMS, forged paintings and defective pixels, the creepy smile of a tycoon, the politician’s tongue, and the shadows of fly-by-night operators repeatedly breach the social contract through perverse pleasure fantasies and subterranean nightmares.

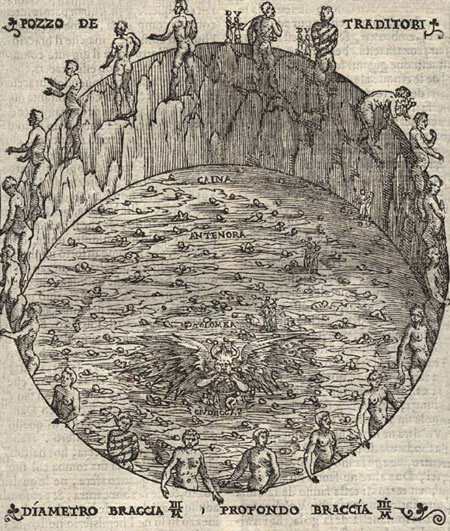

It is believed that the heart of the traitor is the coldest heart of all. The ninth circle of Dante’s Circles of Hell is represented by a frozen underworld lake called Cocytus—a sort of Death Valley full of whirlpools and oozing lament.4 Here, various classes of traitors coexist—having betrayed kindred, country, guest, and benefactor.5 Living through an Age of Extremes, this cosmology of cold suffering intersects with the climactic acceleration of the Anthropocene, registering human impact on the Earth’s climate. As part of the “dismal hole” of punishment in the deepest zone of hell, there is the ultimate fear of being openly identified as the accused.6 However, for retribution there must be a general consensus on what an uncorrupted polity would be.

“Evil is unintelligible,” Terry Eagleton writes.7 Corruption, on the other hand, is readable, reproducible, and profitable—often coextensive with the state’s socioeconomic development patterns and performing an illicit union with its daily network of administration.8

Corruption begins where visible labor becomes invisible, and invisible labor becomes visible. It is in this corridor that it “acts out,” and reenters the body politic as a sentient character, passing the stench of capital from body to body, as if an uncontainable viral flu.

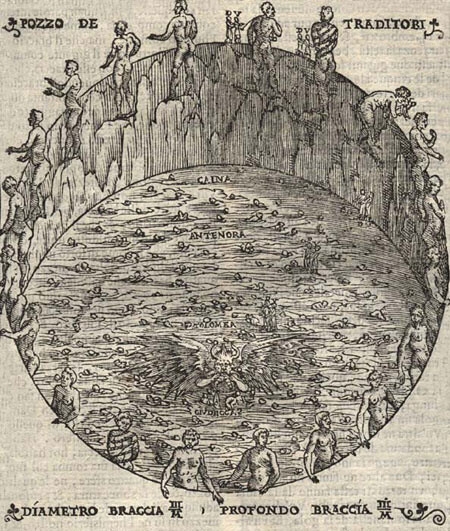

We are confronted with a gloved hand suspended in midair and plotting … something. This hand appears dislodged from a body, as if for a magician’s euphoric unveiling or as Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” gone rogue to challenge a self-interested model of laissez-faire economics by re-presenting an exuberant constellation of interior life and the body politic as deep space.

Susanne M. Winterling’s CGI work Vertex (2015) casts a bodily snapshot that moves beyond the surface pleasures of capitalist stimulation to consider the skin symbolically as a vulnerable organ. The lens probes a microscopic environment that sheds a deterministic perspective for a polyvalent one. In epidermal memory, the artist recalls Chernobyl rain, stunted toxic beings, and bioluminescent creatures swarming like a membrane of keratinocyte cells. In this inside-out gaze, the skin’s loss of haptic sensitivity is projected as a rupture in the physiological frontier between self and world—and thereby, as the inability to defend oneself from evil forces, be they bacterial, sexual, racial, or political.9

In this stealthy hand’s repetitive gesture where interlaced thumbs and fingers produce an infinity loop, there is also the rise of corruption as a nonevent, providing action without confrontation. As critic Jan Verwoert writes in his recent essay “Torn Together”: “Acts of corruption are elaborate disappearing tricks on the stage of common desire. They even out what should cause no ripples. Things go smoothly if what comes to pass happened as if it hadn’t.”10

The day laborer and the cognitariat are equally implicated in this realm and made subservient to the uncanny sweep of the veiled hand of corruption.

Like acid rain, corruption is a lethal blend of the natural and the unnatural, corrosively turning internal mechanisms into parasitic rituals.

In the Machiavellian account of corruption as “a generalized process of moral decay,” it inevitably infects the vital organs of the body politic and poses the looming threat of political instability, while eroding social virtues of the idealized Republic.11

Artist Pio Abad treats the auction as an archeological site for excavating an astonishing range of unwieldy loot that exchanged hands under the martial regime of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, from Georgian silverware to Old Masters paintings. Through the fetishistic tendencies of this illegally amassed wealth, the art object is put to task as an insignia of myth-making and legitimation—mobilizing a repressive political imaginary.

Under the Marcoses rule, visual art and its display became a vital aspect of civilizing rituals brought outside the canonized Western museum and into the bureaucratic chambers and flamboyant private residences of authoritarian governance. The aesthetic condition of fraud thus became construed as an elite complex transacted across schemes of modernization in the Philippines.12 As Arturo Luz, once director of the Metropolitan Museum of Manila, said: “She’d come and pick things up whenever she wanted, even in the middle of the night … There was no accounting, no questions asked.”13

In his series The Collection of Jane Ryan and William Saunders14 (2015), Abad creates a set of postcards deploying the Old Masters paintings that include works by Botticelli, Goya, Tintoretto, Titian, and Gauguin, which were shuttled in suitcases and private planes to be kept under guises over decades and eventually sequestered from Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos to be auctioned off on behalf of the Philippine Commission on Good Government. With several paintings in this “collection” considered fake, these postcard works perform as storytelling devices, illicit souvenirs, and forensic traces revealing larger consequences of the loot as an unauthenticated history, eerily echoing feudal patterns and the generational spread of oligarchic power in the present day.

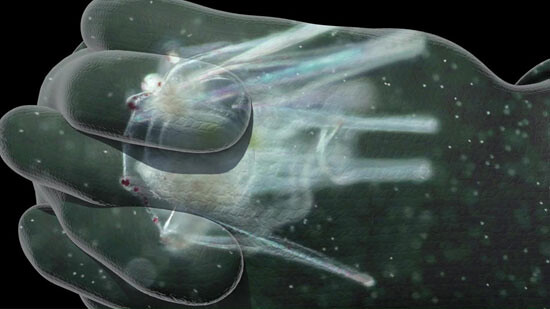

“We’ve had enough rotten meat. Even a dog wouldn’t eat this.”

“It could crawl overboard on its own.”

“These aren’t worms.”15

Jean-Luc Godard has declared: “Cinema is the most beautiful fraud in the world.” We often forget that corruption is also cinematic. A scene that perfectly illustrates the revolutionary economy connecting the moving image and deception is the famous breakfast scene in Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, with the opening act entitled “Men and Maggots.” It is 1905, aboard the Potemkin—a vessel of the Imperial Russian Army’s Black Sea Fleet. Matyushenko and Vakulinchuk are the two sailors who begin to deliberate over the need to support workers at the revolutionary frontlines. Meanwhile, the crew sleeps in the lower decks. It is when rotten meat arrives on the scene that the brewing discontent becomes concrete. The presence of worms is an organic signal reflecting the fact that the crew is being regarded as lesser humans aboard the ship’s symmetries of power. The ship doctor Smirnov inspects the liveness of decayed matter as his pince-nez transforms into a magnifying glass, a sort of evil eye evaluating the border between the edible and the inedible.

Instrumental in Potemkin’s creation of propagandist shock reflexes is the close-up, which in Eisenstein is as critically deployed as montage.16 Though properly speaking, for him this composition is not so much a close-up as it is a “magnification”—a large-scale shot to designate qualitative meaning—which in this case unites the individual and the social body in opposition to state authority. After this tipping point, the act of rebellion becomes a contagion as the resounding call of mutiny spreads forth from the sea back onto the land. Eventually, Vakulinchuk’s martyred body acts as a source of raw evidence with the words: “Dead for a spoonful of soup.”

Inversely signified by this historic rebel ship is the anonymous repression in vessels ferrying people across international maritime borders today—sinking amid news headlines, perilous water routes, and the forming of a subhuman sea-state. The ship as Foucauldian heterotopia has transformed into the generic boat of refugees, traffickers, and state agents that is a more complex human geography—an emergent space of death-life where irresolvable desire and frantic rituals of escape, corruption, and apathy assemble together.

In this parallel economy of transit, the will of individuals to exit wrecked sovereign territories is subjugated as contraband implicitly, in the same measure as an item of piracy. There is no real safety zone as the harsh limits of relief and assistance transfigure into nightmares of insufficiency. Within a perplexing mix of aspiration and desperation, that boat comes to be designated as corrupt infrastructure traversing a sinister scenography of global governance.

Corruption may be the still valid universalism in our midst, resonant since antiquity and continuing to find its strength as the invisible institution of neoliberal knowledge society, tasked with the administration of our collective depression.

Might it be possible for the artist as trickster to harvest the productive capacity of corruption’s gestural performance—its speed, scope, double economy, and antisystemic drive?

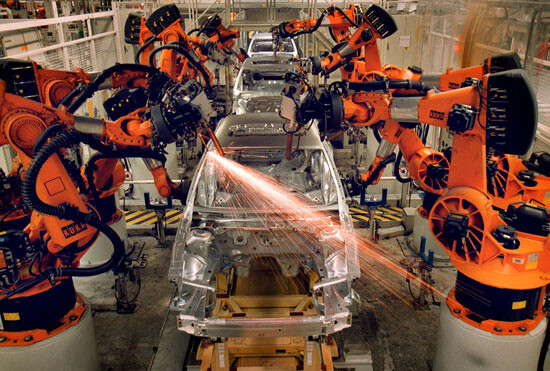

Some months ago, at a Volkswagen production plant close to Frankfurt, a robot being programmed for assembly processes by a small team ended up acting out malevolently and crushing a twenty-two-year-old worker to death.17 While this apparent “killer robot” erred on account of human imprecision, this episode may be observed metonymically as a reversed loop of machinic evolution. A postindustrial dystopia is activated in choreographies of human-machine dysfunction—performing as live threats in the daily pursuit of zombie capitalism.

While the industrially crafted bodies of the car and the robot share an affinity, the illicit action of the robotic agent reverses the terms of agreement between object and subject as well as producer and means of production. Through a dramatic “unmaking” of the mechanized libido of the production unit, this proximity between artificial labor and the laboring human body becomes caught up in scenes of counterattack. Corruption is enacted here at the level of human consciousness—concerning the deeper crises of individuation within a glitched system where new forms of catastrophe await us.

While bodies assemble in states of multiple crises, dispossessed and upon unstable grounds, the shared condition today appears to be that of an entrenched loneliness and systemic corruption. In muddy times of planetary retrograde, we are bound together by separation, by relationship shadows—specters of prior intimacy, and partial fulfillment in the machinic present.18

It is in corrupt affairs that pleasure is resurrected as a collective being and a dissolving-together, no matter the costs involved. If corruption is defined as “a symptom that something has gone wrong in the management of the state,” then it is not simply a matter of identifiable agents risking socioeconomic subversion of the market system.19 According to Alain Badiou, it is in the running of an electoral democracy under the forces of capitalism that foundational corruption is instituted such that it becomes an essential condition.20

In the aftermath of robotic cannibalism and anthropogenic shifts, as new conglomerates of right-wing governance join a general decay of the body politic, corruption operates as both a counterhistorical project and a back entry for “unofficial” histories. On the one hand it threatens to lock us into an exclusively delivered image of history, with a promise of emancipation. While on the other, historical becoming involves contaminating the flows of major narratives of modernity through a means of editing—introducing characters, diversions and sequences of “eternal recurrence.” Corruption survives as a figure of story-telling, the truth of which remains murky and to be discovered. It will be the last of the undead to die.

Charles W. Mills, “Body Politic, Bodies Impolitic,” in “The Body and the State: How the State Controls and Protects the Body,” ed. Arien Mack, special issue, Social Research, vol. 78, no. 2 (Summer 2011), 583–606.

I am referencing this key concept as described in Ernst H. Kantorowicz’s The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

See Jean-Luc Nancy, Corpus, trans. Richard A. Rand (Bronx: Fordham University Press, 2008), 5–8.

Dante, The Inferno of Dante Alighieri, trans. Seth Zimmerman (Bloomington: iUniverse, 2003), 224–27.

He began: ‘You want me to return to a despair / So painful that even before I relate the deed / Its remembrance is more than my heart can bear.’” Ibid., Canto XXXIII.

Wallace Fowlie, A Reading of Dante’s Inferno (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Terry Eagleton, On Evil (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 2–6.

Bruce Buchan and Lisa Hill, An Intellectual History of Political Corruption (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 2–9.

It is worth recalling here Frantz Fanon’s thinking around the “epidermal schema” investigating the alienation of the Black figure and the reactive forces at play.

Jan Verwoert, “Torn Together,” in “Supercommunity,” ed. Natasha Ginwala et al., special issue for the 56th Venice Biennale, e-flux journal 65 (May 2015) →

Buchan and Hill, An Intellectual History of Political Corruption, 2–9.

See Pio Abad, Some Are Smarter Than Others*, artist’s publication (London: Gasworks and Hato Press, 2014).

Quoted in Fox Butterfield, “Art Collection, Imelda Marcos Style,” New York Times, March 12, 1986.

“Jane Ryan” and “William Saunders” were the false identities used by Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos to register their first Swiss bank account at Credit Suisse in Zurich in March 1968.

Sergei Eisenstein, Battleship Potemkin (1925).

James Goodwin, Eisenstein, Cinema and History (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 199–205.

“Robot kills worker at Volkswagen plant in Germany,” The Guardian, July 1, 2015 →

See Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide (Brooklyn: Verso, 2015).

Buchan and Hill, An Intellectual History of Political Corruption, 7–8.

Alain Badiou, “Democracy and Corruption: A Philosophy of Equality,” Verso blog, February 14, 2014 →

This essay was initially developed as part of the lecture-presentation Corruption: Three Bodies with Julieta Aranda featuring e-flux journal at the ARENA, “All the World’s Futures,” 56th Venice Biennale. Special thanks to all contributors to the exhibition “Corruption: Everybody Knows…,” opening November 10, 2015 at e-flux in New York.