It was not long ago that the Western art system was an object of intense focus and emulation throughout China. Beginning with the enthusiastic introduction of Western philosophical writings and Modernist artworks in the 1980s, this one-way exchange crystallized into a dichotomy, with China and tradition on one side, and modernity and the West on the other. Post-Mao, Chinese intellectuals embraced a progressive narrative of history wherein Western Europe and North America represented the contemporary standard to which China was forced to catch up. As Shi Chong, an artist and professor at the Qinghua Academy of Art in Beijing, put it: “In the 1980s, it was still a learning process. On the one hand there was Western classical art and on the other there was Western modern art. We were in the middle of the two processes as they interweaved with one another.” But beginning in the 1990s, the rapid rise of China’s position in the global economic hierarchy set in motion a process of de-internationalization. This initially imperceptible shift has surfaced more clearly since the worldwide economic downturn of 2008. As a result, for Chinese art practitioners the globalization of the contemporary art system has been accompanied by the disappearance of the international, both as an aspiration and as a horizon.

In the intervening years, de-internationalization has evolved into a new historical condition shaping the thoughts and feelings of Chinese art practitioners, especially among those born after 1980. Like their peers in other fields, many young artists and critics were exposed to Western culture at a young age through the proliferation of English-language training programs, a gift of globalization. Moreover, the consumer society that has grown with the economy has no shortage of Western concepts and products. After high school, many students are sent to North America and Europe for higher education. Having lived in both worlds, it is perhaps not surprising that they feel empowered to reject the international realm and claim, with much more certainty than their predecessors, that China and the West are equal. There is a sense of unprecedented conviction and optimism about what is happening in China socially and politically, and this means that the image of the West as a place of promise and progress has faded. In this respect, it is difficult to separate the process of de-internationalization from one of de-Westernization. With China now the world’s second-largest economy, the West and its democratic values are generally portrayed and perceived as a model in decline, both in the rhetoric of the Chinese government and in the sentiment of the general public.

The 2008 economic slowdown brought a noticeable reduction in demand for Chinese art, especially overseas. However, the domestic market rebounded quickly. In a matter of years it not only compensated entirely for the loss of international demand, but became a powerful force in its own right. The current domestic Chinese market for contemporary art consists of a relatively steady pool of private collectors supported by a significant amount of government resources. Some collectors have even opened museums of their own, and in some cases, these museums have received substantial reductions in rent and even investment capital from local governments. This trend is especially pronounced in Shanghai, where the city government has taken many of the remaining venues from the World Expo of 2010 and offered them to select individuals who can afford to turn them into museums and art venues maintained by private funds. The government is also committed to supporting the booming art fair culture in the city, with three fairs each year. At the same time, the city remains one of the strictest in terms of content censorship and ideological control. Like the Shanghai Biennial, the fairs are subject to a thorough inspection by government officials prior to opening.

The slow rejection of Western influence has grown harder to detect as Chinese participation in the locality that we call the global has increased dramatically. In the 2013 Venice Biennale, more than one hundred exhibitions featuring Chinese artists and curators were organized by Chinese institutions, funders, and artists. More and more galleries from China have taken part in art fairs in such prime locations as London, New York, Basel, Madrid, Singapore, Taipei, and Hong Kong.

Since 2005, when the Chinese government made the decision to participate in the Venice Biennale—but could not fully join due to the SARS outbreak—there has been a conscious effort by the government to promote its brand of contemporary art on the international circuit. Government-supported survey exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art have been and continue to be mounted in museums and temporary venues around the world, none bigger than “China 8,” staged in Germany in the summer of 2015. Eight exhibitions in nine museums across eight German cities opened simultaneously, featuring five hundred works by 120 contemporary artists from China. Codirected by Walter Smerling, director of the Museum Küppersmühle, and Fan Di’an, director of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, this event was the biggest state-level exhibition of Chinese art in Germany. The participating artists consisted of both non-official artists and official artists, including the likes of Xu Jiang, the director of the National Art Academy in Hangzhou. This event intended to demonstrate that the Chinese government was and is open-minded enough to endorse and present contemporary art. For the Chinese art community itself the government has proven to be a promising promoter, offering much-needed platforms and opportunities. What is not discussed, however, is how this relationship shapes the direction of artistic practice.

The de-internationalization of the contemporary art world in China is further concealed by the Chinese art system’s ability to continuously adopt terms and references from its Western counterpart while at the same time giving them a Chinese interpretation. In 2001, a new media art department was established in the National Art Academy, with many other art academies subsequently following suit. The artists and teachers who helped push for this change considered it a covert opportunity to generate a more progressive teaching program and to break away from the institution’s conservative and stagnant atmosphere. Privately, this move found its spiritual origin in the radicalism associated with the emergence of new media art in Europe at the end of the 1980s. But publicly, the artists and teachers behind the new department linked it to the society-wide and not-at-all-radical obsession with new technology in China at the time.

In 2005, experimental art was first offered as a major at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing, and was established as a department two years later. In 2014, it gained semi-autonomous institutional status, becoming the CAFA School of Experimental Art. Currently, around fifteen art schools across the country provide courses in experimental art in their official curriculum. The integration of “experimental art” into the curriculum of Chinese art academies over the last decade has seemed like an inevitable step in a process that begun when Deng Xiaoping’s open-door policy cleared the way for foreign investment in China in 1978. It exemplifies the leap of the academy out of a single, realist model of artistic production and into a much more diverse landscape of methods and training—practices which, of course, have helped prepare the Chinese art system for a more advanced level of international competition.

The three missions of the CAFA School of Experimental Art are, first, to sort through international examples of the theory and practice of modern and contemporary art; second, to establish an academic structure for experimental art in contemporary academic art education; and finally, to explore feasible ways of launching an international modern art trend that is rooted in Chinese characteristics. To fulfill such a vision, the teachers at the CAFA School of Experimental Art direct their students to focus on three things: “traditional language translation,” “research on experimental art,” and “material language expression.” As proof of its academic achievements, the CAFA School of Experimental Art highlights published research carried out by its graduates and professors on certain folk art traditions, such as written Chinese language, traditional farming tools, and crafts like paper cutting and shadow puppetry. The choice of folk art subjects, concerned mostly with tradition, conveniently avoids contemporary social, political, and intellectual issues in China. This emphasis on folk art in a program intended to update rigid academic teaching rooted in Soviet models from the 1950s evinces the continued influence of Mao’s 1942 Yan’an speech demanding an art in the service of “workers, peasants, and soldiers.” However, while in Mao’s era folk art was an important channel for communicating political messages, today it no longer expresses any distinctive political position. This is why it is the official art form of choice at the CAFA School of Experimental Art.

China’s process of globalization unfolds mostly on its own terms and in its own ways, while consistently referring to a Western vocabulary to evoke empathy and familiarity. Through the use of terms and references from Western discourses, China, on the one hand, projects the image of integrating itself into the international community and situating its own development within the Western art historical narrative, while on the other hand insisting on developing its own identity and proving the legitimacy of its own model. The process is rife with contradictory emotions and ambitions. Sometimes the Western art system is regarded as superior and worth emulating, while at other times it is a bully that exercises power through the inclusion or exclusion of Chinese artists in its exhibitions, collections, and art historical narratives. The fluctuating feelings of the Chinese art community towards the West spring from the community’s anxiety over its own self-definition and self-perception. The ultimate goal is actually to fully develop its own subjectivity and its own art system, comparable in sophistication and influence to the West’s.

Since 1989—around the time when the exhibition “Magiciens de la Terre” was held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris—Chinese contemporary art has gradually appear more frequently in exhibitions organized by Western art institutions, riding the wave of globalization in the art world. In the 1990s, Chinese artists, curators, critics, and dealers actively participated in promoting the brand of Chinese contemporary art abroad, while immersing themselves in constructing a domestic art system based on their own knowledge and understanding of the Western art system. They often attributed problems at home to an underdeveloped art system lacking commercial operations and academic engagement. They lamented the fact that in the international art world, Chinese art was like a plate of spring rolls—present as a kind of appetizer but never as the main course.

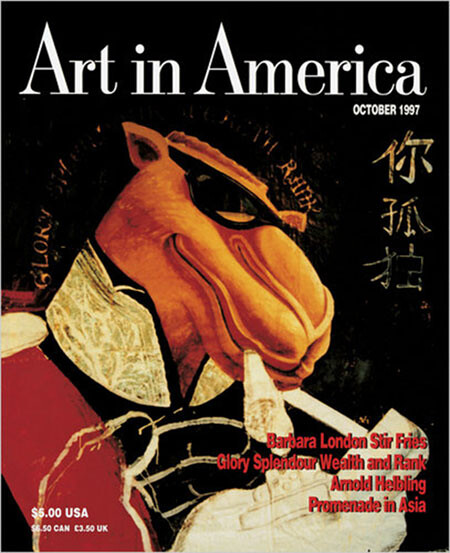

From 1995 to 1998, Shanghai artist Zhou Tiehai created a series of seven fake covers of international magazines such as Newsweek, Flash Art, FACTS, and Art in America, placing images of his artworks or himself on the front. He realized that an artist needed to be on an exclusive list in order to be welcomed into museums and galleries, to receive the attention of art critics, and to be highlighted by the media. This list was primarily Western. Zhou’s series was prompted by an incident at another artist’s studio. A French photographer who was doing a special feature on Chinese contemporary artists visited this artist’s studio, but confessed that he had never heard of the artist before. To Zhou, it became clear that Chinese artists needed to become a part of the international exhibition and museum circuit before they could get any recognition in the art world.

This anxiety among Chinese artists vis-à-vis the global art market was aggravated by the marginalization of contemporary art practice and the tightening of ideological control that occurred after the Tian’anmen Square demonstrations of 1989. There was a great deal of tension between the authorities and contemporary artists, whose performances and exhibitions were often censored or completely shut down. These two anxieties—domestic censorship and the position of Chinese artists within the global art market—shaped Chinese artistic practice and thinking in this period. In 1996, Zhou Tiehai created a sound piece entitled Airport. It consisted of announcements of international flight departures from the Shanghai airport—“Ladies and gentlemen, boarding has commenced for flight 949 from Shanghai to Tokyo”—broadcasted throughout the exhibition space. One announcement said that a flight bound for Kassel was delayed until Documenta took place the following year. This work vividly illustrated the urge of Chinese artists to participate in the international art world. The surge of international biennials during this period gave these artists hope, opening new platforms for international participation that went beyond the existing Western structures of national museums and art institutions.

Domestically, the 1990s witnessed the gradual transition of the Chinese art world from a mixed community of idealistic intellects, radical conceptualists, pragmatic revolutionaries, and naive entrepreneurs to one of market believers. While the government promoted the market and economic growth as the new national ideology for all walks of life, intellectuals and artists dove right in, mistakenly considering it a means to a more open society. Pragmatically speaking, the marketization of art also demonstrated to the government that art had value, thus giving it a legitimate status in China. The reformist liberalism of the time imagined a market-driven liberation of society from the state. The government, however, used this zeal for the free market to integrate a great number of intellectuals and educated elites into economic activities that depended on political access and privilege. Some of those who would otherwise have taken to the streets became invested in political stability.

At this time, state-run art magazines gave considerable space to reports from art fairs and lists of auction prices. Former translators of Western art history books and emerging art critics set out to organize a biennial that aimed to emulate the Venice Biennale, especially in its origin as a trading platform. They also attempted to launch an art magazine entitled Art Market, with a core mission to promote market discourse in the art world. Some of these ideas seemed liked misreadings and mis-translations of practices from the Western art system, but they nonetheless had a profound impact in China. There was a pervasive sense of excitement about the concept and language of “business,” which evoked a kind of formality—something regulated, orderly, and efficient that can be taken seriously and yield a livelihood, rather than being just a cultural and idealistic pursuit. This business mindset spread throughout the Chinese art world.

The general perception and historical narrative of this period is thus dominated by accounts of market success and international recognition garnered by a small number of Chinese art movements, christened and heavily promoted by art critics and dealers. With this rise in global participation, another kind of unease would soon cast a shadow over the Chinese art community. As artist Zhang Peili put it:

I envy those Chinese painters prior to the Ming Dynasty. They were more or less free. There was not so much contact between Chinese culture and the West. The infiltration of Western culture into China was very slow then. After the Ming Dynasty, there were more and more missionaries. Many artists were court painters previously. Then Western paintings started to come in. Artists who worked in China before the Ming Dynasty might not have had to worry about what was Chinese. Like many artists in the West they believed that “what is me” is the most important thing, instead of thinking about “what is Chinese, what is French.”

Clashes between Chinese and Western cultures intensified as a result of increased contact. Many Chinese artists experienced various levels of uneasiness through this encounter. Artist Zhang Xiaogang said that it was difficult to continue making art after he returned to China from an extended visit to European museums:

I was not so interested in what was happening in China then. My whole brain was awash in the West. I kept thinking that China could not reach the same level, and was only at the very beginning. I did not pay any attention to what was happening here. My focal point then was to look for my own position, even to think about whether I should continue to paint or not.

This feeling of restlessness resulted not only from the increasing pressure of participating in the international art world. It also came from the weight of a Chinese art system that was coming into its own thanks to the success of the domestic art market. Some Chinese artists felt so uneasy that they decided to exit the art world entirely. In 1996, Shanghai-based artist Qian Weikang made his last video work, Breathing, Breathing, in which the repeated sound of a toilet flushing breaks up footage of TV commercials, of street scenes full of advertisements, and of Qian’s artist friends gathering for parties and other social events. Since then, Qian has not produced anything that resembles visual art, and has not participated in any exhibitions or art events. He has also refused to provide curators with instructions for re-creating some of his site-specific installations from the 1990s, which he destroyed due to lack of storage space.

Since then, thanks to China’s soaring economy and increasing international presence, the country has been the subject of many art exhibitions throughout the world. For example, “China Power Station,” co-curated by Julia Peyton-Jones, Gunnar B. Kvaran, and Hans Ulrich Obrist, toured various venues throughout Europe between 2006 and 2010. Many similar exhibitions have been initiated throughout the West. I have been invited to speak about China at many conferences organized by Western art institutions, and at a certain point I became fed up. In this wave of singling out China as a curious social, political, and cultural phenomenon to study and exhibit, individual artists are canonized and inevitably imprisoned by the collective identity of China.

In China, the art community’s silence when it comes to political issues is one of the most distinctive features of artistic production and discourse today. As already noted, this silence results from the government’s growing support of the domestic art market and its promotion of Chinese art exhibitions abroad. Judging by the market-oriented political and legal reforms it has implemented over the past few decades, the Chinese government has no real interest in developing a social model that can be championed and promoted to the rest of the world, or that can be carried into the future. Similarly, the Chinese art community has no vision for the future, but is only concerned with its own self-interest and self-preservation. As a result, the contemporary art world in China has not broken free from the government’s narrow political vision, and has instead fallen prey to self-isolation and arrogance.

A longer version of this essay was originally commissioned by the Kunstmuseum Bern for the catalogue of their upcoming exhibition “Chinese Whispers.”