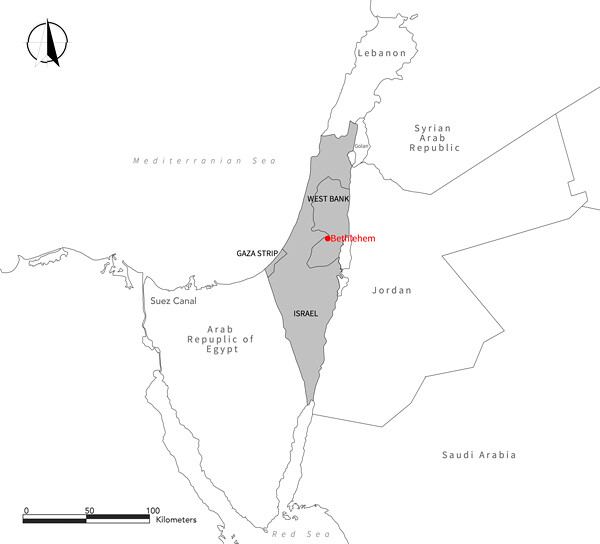

1.a Country

Palestine

1.b Province

Bethlehem Governorate, West Bank

1.c Name of Property

Dheisheh Refugee Camp1

1.d Geographical coordinates to the nearest second

31˚41’38,47” N, 35˚11’02.96” E

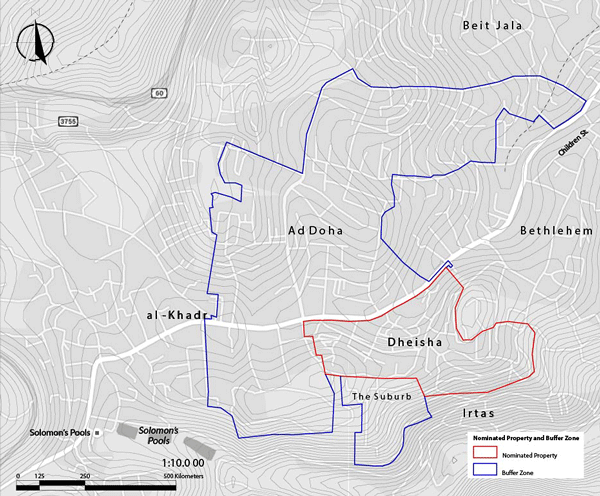

1.e Maps and plans, showing the boundaries of the nominated property and buffer zones

Map and timeline of UNRWA’s 59 Palestinian Refugee Camps in the Levant

Map showing the placement of Bethlehem in the Region

Map of the nominated property and proposed buffer zones

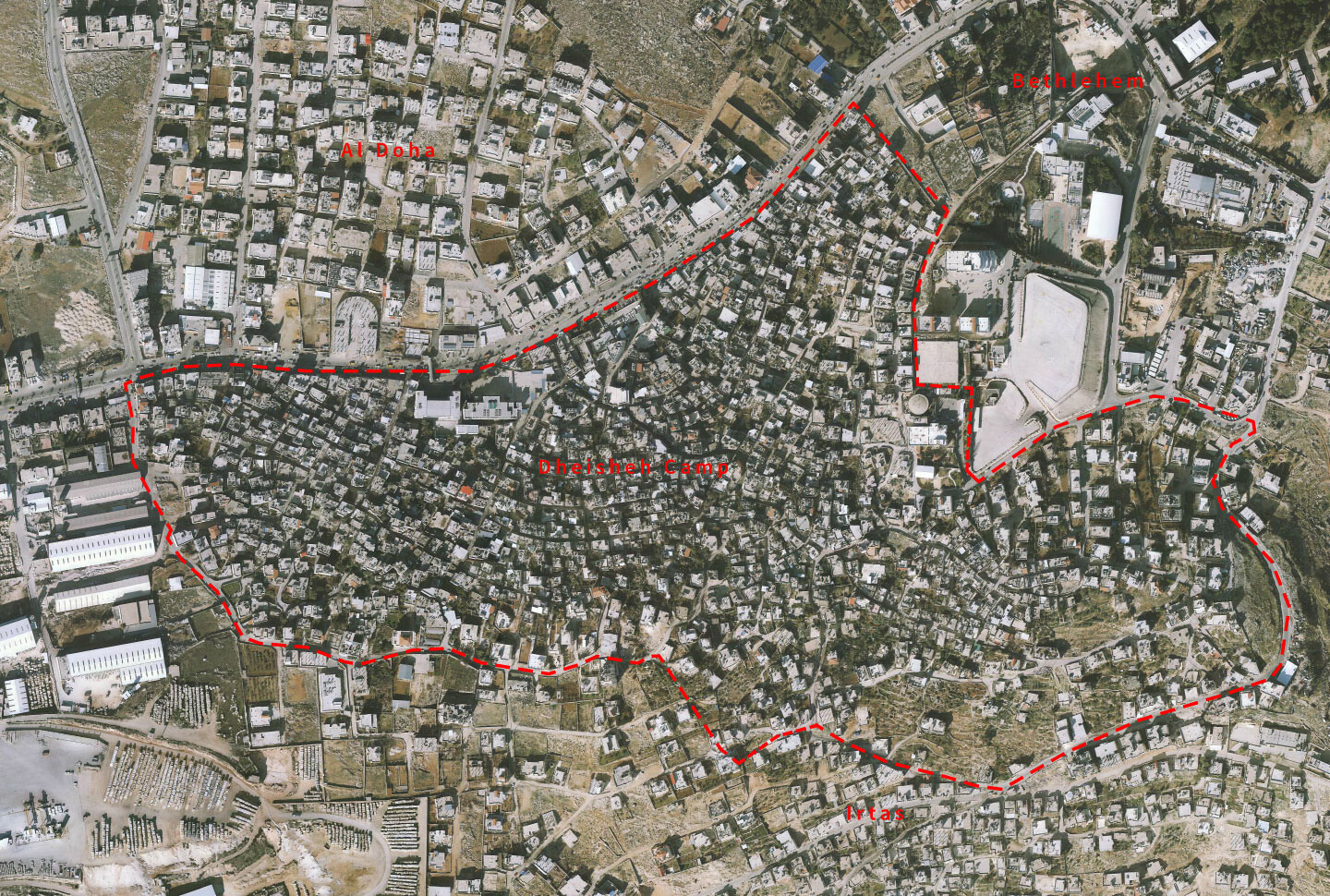

Map of the nominated property

Aerial view of the nominated property

1.f Area of nominated property (ha.) and proposed buffer zones

Area of nominated property: 31 ha

Buffer zone: 186.6 ha

Total: 217.6 ha

1.g Description of the boundaries of the nominated property

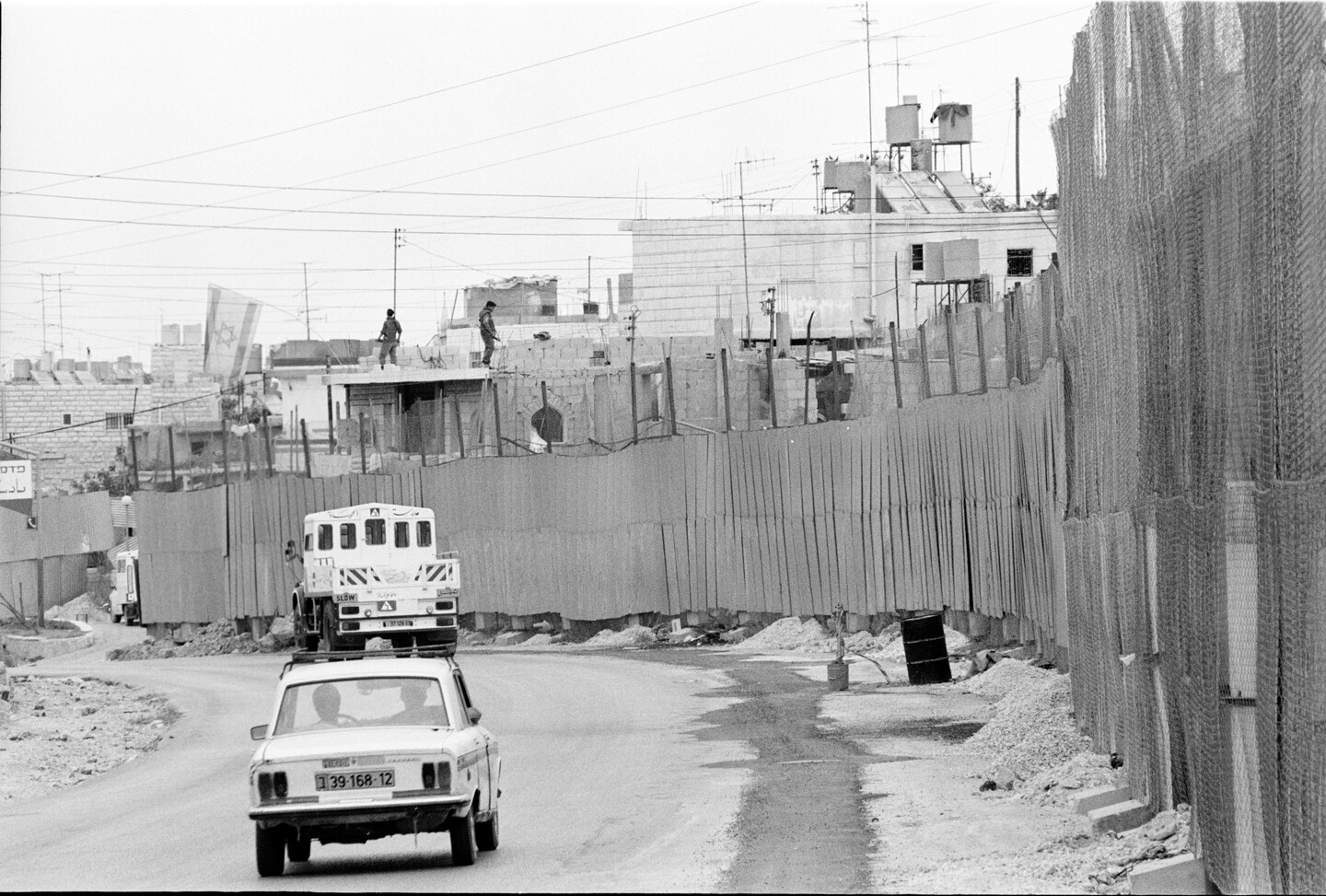

Dheisheh Refugee Camp is located on the main road that connected Jerusalem with the southern region, and thus played a strategic role for the Palestinian resistance during the 1980s. During the first Intifada, the Israeli army built a fence and a gate surrounding the camp in an attempt to protect settlers using the road. Photo: 1987–1993, UNRWA Archive

Dheisheh Refugee Camp can be identified by the official borders established by UNRWA upon the camp’s foundation in 1949.2 It was originally established as a refuge for 3,400 Palestinians from more than forty-five villages west of Jerusalem and around Hebron. The 1949 border of the camp is thus both a trace and testimony of the Nakba.3

Camp borders exclude refugees from the body of rights granted by host states to their citizens, yet the Palestinian Authority does not hold full sovereignty over the land on top of which Dheisheh sits; it is technically still leased to UNRWA by the Jordanian government. The border of the camp is thus not simply a physical and symbolic element, but marks the extraterritorial dimension of the camp in what is already a political state of exception; an enclave in a quasi-state territory.4 Palestinian refugees in the West Bank consider the Palestinian Authority a “host authority,” similarly to how Palestinian refugees in Beirut may consider the state of Lebanon.

Despite the fact that Palestinian refugees in Bethlehem don’t vote in local or national elections, they informally influence local and national politics and hold positions inside the Palestinian Authority. There is no municipality in or sovereign over the camp, but there is a popular committee that functions similarly to one.5 While UNRWA’s mandate is to offer services to refugees, it also intervenes in the camp’s administration.6 Therefore, the border of the camp also marks the exceptionality of its internal management.

For the past seven decades, refugees have opposed any act that could erase the borders of the camp and blend it into the city in fear that it would normalize political injustice and undermine their right of return. The border of the camp is thus a place that props open a political horizon and connects its residents to their place of origin. Yet with a current population of approximately 15,000 residents, Dheisheh has been forced to grow. By preserving and profaning the border, residents have been able to expand beyond the original camp limits while still maintaining their identity as refugees. Al Doha City and Al Shuhada Suburb are two buffer zones to Dheisheh that have both been built by refugees.

1.h Description of the boundaries of the proposed buffer zones

Al Doha City

Al Doha City Municipality. Photo: Campus in Camps

In some parts of the camp the border is blurred by the spillover of its built fabric into other areas. Refugees living in the adjacent area of Doha, for example, view the camp as the center of social and political life. They see it as closer to their homelands and more connected to their right of return to the original villages from where they were displaced during the Nakba than where they live.

Starting in the 1970s, refugees from Dheisheh seeking greater privacy or more space started to move to Doha. As a result, the Municipality of Beit Jala withdrew the services that it had been providing to the area. Doha was formally established as an independent municipality in 1997, at which point it was able to offer services to its population. In 2004, Doha was renamed after the capital of Qatar, which gave a large grant to widen the main road that connects the new municipality to the city of Bethlehem.

Today, the population of Doha is primarily refugees coming from different camps south of Bethlehem. Less crowded than Dheisheh, this “refugee city” lacks the social relations that exist in the camp. Hajj Nemer, the mayor of Doha, expresses the relation between the camp and Doha in these terms:

When I walk through its alleys, I feel completely different. The living memories and stories always come to my mind. I am more attached to Dheisheh camp than Doha, although I have been living here since 25 years. The wide social bonds extending from Dheisheh have helped me to be elected as the Mayor of Doha city. When I go to Dheisheh, I feel the difference. People who lived in Dheisheh are the same ones who are living in Doha; but the only change is the place and the lifestyle. My behavior changes when I am at Dheisheh. I deal with people in a different way. The interaction with the daily events is stronger in Dheisheh than in Doha.7

Al Shuhada Suburb

Al Shuhada Suburb. Photo: Campus in Camps

The camp also spills over into Al Shuhada Suburb. Houses first began to appear on the land at the beginning of the 1990s, and were serviced by the nearby municipality of Irtas. In 2005, Irtas surveyed 210 plots on a total area of 162 dunam with the aim of including the area within its municipal borders. After residents refused, it withdrew its services. Electricity was subsequently brought by cables strung from Dheisheh. On November 26, 2012, the local committee of Shuhada made a formal request to be included within the Dheisheh Popular Committee’s jurisdiction. The request is still pending.

Similarly to in Doha, the residents of the suburb were confronted with the question of their refugee identity the moment they moved out from the camp. Despite the fact that more refugees live outside Dheisheh than inside, the fear of leaving is the fear of normalization: the fear of having a normal life and forgetting about the right of return.

The following conversation between Ahmad and Qussay, two refugees who both grew up but no longer live in Dheisheh, reflects the implications and questions regarding the identity of refugees living outside or inside the camp.

Ahmad: I am entering a new stage of my life by moving outside the camp, to the suburb. There are a lot of things I am wondering about and would like to know from someone who has a strong connection with the camp but lives outside of it. What is it like to live outside the camp?

Qussay: The easiest answer could be that living outside the camp is like living in a hotel. I spend my life in the camp, because most things don’t exist in Doha. On a personal level, I don’t know my neighbors very well. I don’t even recognize them. There is no conversation between us except for on the social occasions when you have to invite them. I don’t spend time in Doha. When I leave home, I come to Dheisheh.

A: What made the camp attractive? Bethlehem City has attractive things. Why do you stay in the camp?

Q: I don’t know, maybe because of the relationships I established when I lived there; through school, Ibdaa, Feneiq, and working in the camp. My social network is in the camp. In Doha I feel that to a certain extent everyone is living on their own—not totally alone, but not as it is here in Dheisheh. There isn’t a single falafel place in Doha! And one that would open would close after two months. No one would go to it. Even non-refugees come to Dheisheh.

A: Is there something emotional in these visits? Or is it just to find things?

Q: Of course there are emotional aspects. When I introduce myself, even though I am living in Doha, I say I am from Dheisheh. People know Dheisheh: it has sumud [steadfastness]; it’s a highly aware camp. You feel like you are coming from a strong place. The problem is, if I introduce myself as coming from the camp and someone says to me “but you’re not living there,” I perceive it as humiliation.

A: Why? You don’t live in Dheisheh.

Q: I am not living in Dheisheh, but I am from Dheisheh.

A: I don’t get it.

Q: The Dheisheh style, the way things move. For example, I have never seen a demonstration against anything in Doha for as long as I’ve been living there. The people can’t gather about anything except the rise in prices. And even for this, what they did was walk towards the main entrance of the camp.

A: Would you also say that the camp is not just a place, but an idea?

Q: Yes of course. The idea isn’t limited. Would someone live the camp the same way as they would live in Paris? Or vice versa? What are you afraid of in preparing to live outside of the camp?

A: It’s not about being afraid; it’s something about memories. For human beings all over the world, not only Palestinians, memories are their homeland. That is, the place where you have memories is your homeland. And my memories are only in the camp, not in Beit Etab, my original village; not in Bethlehem, not anywhere else. And so I am afraid about losing these memories and how that might affect my life.8

The application of Dheisheh Refugee Camp is the example for the serial nomination of all 59 Palestinian refugee camps in the Levant.

See ➝

Nakba, translated in English as “tragedy,” is a term that refers to the expulsion of two-thirds of the Arab population living in historical Palestine between 1947–1949 by Jewish militias. The term is used to mark not only an event in time but the ongoing tragic events perpetrated by successive Israeli governments, including house demolitions, land expropriations, movement restrictions, extrajudicial killings, and mass incarcerations.

The Palestinian Authority was created during the Oslo Peace Process with a limited form of self-governance restricted to areas A and B, a total of approximately 40% of land in the West Bank, and its mandate was supposed to terminate in 1999 with the establishment of a sovereign and independent Palestinian state.

Popular committees began to emerge informally during the first Intifada and evolved into formal bodies representing the camp during the 1990s with the constitution of the Palestinian Authority. See Sari Hanafi, Governing Palestinian Refugee Camps in the Arab East (Beirut: Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, 2010), ➝

Riccardo Bocco, “UNRWA and the Palestinian Refugees: A history within history,” Refugee Survey Quarterly 28, nos. 2–3, UNHCR 2010, ➝

Naba’ Al-Assi, The Municipality (Dheisheh: Campus in Camps, 2012), ➝.

Ahmad Laham and Qussay Abu Aker, The Suburb (Dheisheh: Campus in Camps, 2012), ➝.

Refugee Heritage was made possible by the Decolonizing Architecture course at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, Sweden.

Category

Subject

Refugee Heritage is a project by DAAR, edited and published by e-flux architecture and produced with the support of Campus in Camps, the Foundation for Art Initiatives, the 5th Riwaq Biennale and the Decolonizing Architecture course at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, Sweden.