In the comedy of errors that is US car culture, contradictions and cross-purposes seem to thrive. The mid-twentieth century monovalent highway network replaced a finely grained rail network to conform with default modernist scripts that claim newer is better. In perennial cycles of obsolescence and replacement, new infrastructure technologies have overwritten existing networks, however intelligent or efficient they may be. Adhering to false logics of traffic engineering that linked roadway width to traffic volumes, those highways were doomed to both continually inflate in size and never relieve congestion. While reliant on a fuel that provokes military entanglements and destroys the planet’s atmosphere, car manufacturing has also been treated as a key indicator of employment and economic health. And driving—often a dreary and time-consuming chore performed by gripping a wheel and staring forward at a road—is, at least in car commercials, stubbornly portrayed as a luxury; the sexy freedom of rounding curves on wet roads.

As Trump’s Eisenhower-era highway plans and environmental deregulation meet the newest shiny technologies associated with “smart” autonomous vehicles (AVs), what will be the next engineering paradox or myth of luxury? While Trump points to a future in the past, the same modernist narratives still claim that newer is smarter even if the organizations they create are effectively dumber. Celebrating another false logic, AVs are projected to create a “mobility internet”—an internet of things—in which synchronized digital devices attached to everything will finally make the stiff spatial world fluid.1 Again, replacing incumbent networks, new technologies will provide the right answer.

Autonomous vehicle technology is heralded as transportation’s magic bullet, but it is unclear how the advent of the technology will be organized. In ideal projections of a fluid, smart, digital world, AVs in efficient platoons will perfect driving by increasing mobility, saving fuel, reducing emissions, and increasing productivity.2 But if all the major car companies develop automated technologies and sell AVs like the individually owned family car, congestion and vehicle miles traveled (VMT) will only increase. Organizing the AVs in fleets, at first, seems to drastically decrease the number of cars needed. And with no need to pay for the labor of drivers, AV fleets would also initially appear to reduce the cost of travel.3

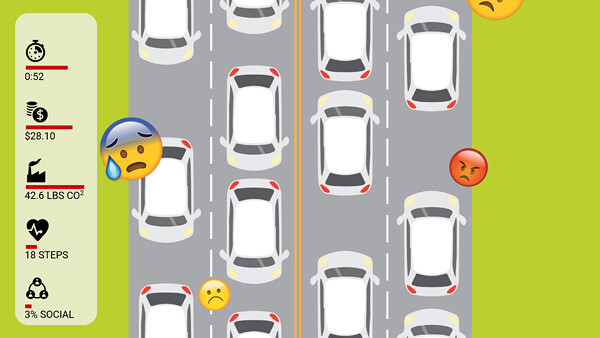

AVs risk having a boomerang effect. Convenience and low cost incentivize AV use unsustainably, inadvertently increasing vehicle miles travelled, congestion, and urban sprawl. Image: Brian Cash, Dan Glick-Unterman, Nathan Portlock, and Miguel Sanchez-Enkerlin.

But there is a boomerang effect. While fleets of ridesharing AVs reduce vehicle miles traveled, increased convenience and reduced cost may lead passengers to take AVs instead of transit and the number of cars on the road to skyrocket. This is just one of several simple spatial variables to consider. Expand the size of every person in the commuter train or subway to the size of a car and it is clear that congestion would overwhelm the counter effects of carpooling and platooning. Larger cities are already experiencing increased congestion because riders are choosing Uber or other ridesharing companies over transit. Considering another spatial variable, if driverless cars increase productivity by allowing passengers to work while traveling, and if there is then less incentive to shorten the commute, AVs might also encourage sprawl. When the magic bullet boomerangs, the optimism turns dire as predictions of increased congestion, emissions and sprawl.4

How then does the automobile industry, the sharing economy, and transit organize its efforts in the face of these uncertainties. And how does the US fund repairs for the broken transportation infrastructure on which all of these efforts rely?

While the habitual response may be to look for a “solution” in the next emergent technology like futuristic flying cars, an alternative response might be to alter a relationship or to rewire the network with a spatial variable—an architectural typology that acts like a switch when placed between existing transportation technologies.5 Whatever the promise of digital technologies, space is itself a technology, an information system in play as well as an underexploited medium of innovation. However heavy and lumpy, it does not need digital devices to make it dance. Digital and spatial networks can make each other smarter, but they can also make each other dumber. The switch, an intermodal node for upshifting and downshifting into transportation of different capacities, may offer the best model for organizing maintenance, innovation, and investment in this shifting transportation ecology.

Imagine the switch located at a transit stop in the suburbs. That stop might have a low ridership because potential riders cannot drive their car to the stop and leave it in a parking lot as it is needed for other purposes throughout the day, or because the train doesn’t take riders to their final destination on the other end of the journey. Faced with these options, a commuter might simply take a car from door to door. But when linked by a switch, AV fleets and transit become reagents with a chemistry that redoubles efficiencies. AVs can deliver a vastly increased ridership to transit, and serve any number of trips that would require a household to own multiple vehicles at rush hours, while also handling the last mile of travel.

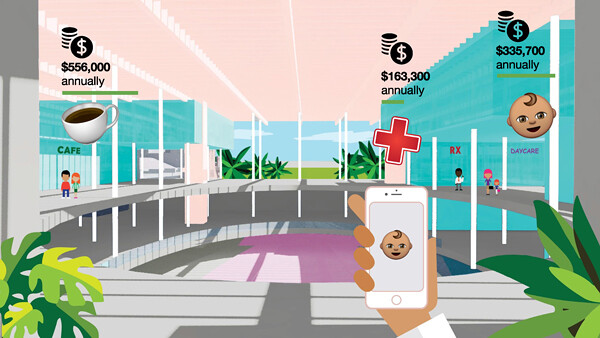

The switch becomes a hub of diverse itineraries and activities, connecting riders to AV’s, mass transit, bike sharing, shopping, and other daily activities. Image: Brian Cash, Dan Glick-Unterman, Nathan Portlock, and Miguel Sanchez-Enkerlin.

In the morning, a suburban commuter can walk or take an AV to the nearest switch, upshift to transit, arrive in town and walk or take another AV to the office. Other family members can organize their trips to work or school in a similar way. And on either end of the trip, any of these riders can arrive at a switch and downshift instead of upshift; the commuter can take a bicycle from an urban station to the office or, on the way home, change clothes at the switch and jog the last mile home.

Linking AVs and transit at the switch reduces congestion, sprawl, and emissions, makes transit healthier, increases AV efficiencies, and potentially even consolidates liabilities. There have been concerns that vehicles in fleets might often be traveling empty, but at the switch, if they can both deliver and pick up, they will rarely be without passengers. While there are many imponderables about liability when individually owned cars are driverless, with switches and vehicle fleets, liability issues at least resemble familiar forms like those for trains or, as some have suggested, elevators.6

The switch is also an urban space and a cultural institution that, by changing habits, has ramifying effects on the shape of cities and suburbs. Having to switch during a journey is usually treated as an inconvenience, but consider a space like Grand Central Station in New York City. More than a train station, it allows for shifting between networks and modes of transportation, and its internal programs like food markets, restaurants, bars, banks, gyms, and other retail respond to time sensitive needs at the different moments of the day. Similarly, the switch could become the hub of complicated household itineraries and activities—the place for food shopping, exercise, violin and ballet lessons, day care, and monitored spaces for students to gather after class and practice. Each activity provides foot traffic for the other. Even if AVs could be perfectly synchronized to function with optimized efficiency, the distances between dispersed destinations and errands increases vehicle miles traveled. Consolidating some of the primary repetitive errands to do with school, work, childcare, grocery shopping, and households adjusts a spatial network to make both spatial and technological networks smarter.

The switch generates revenues and becomes a place where people desire to go to, not only need to go. Akin to Grand Central Station in New York City, a switch not only facilitates multi-modal transit but it also provides amenity and convenience for riders. Image: Brian Cash, Dan Glick-Unterman, Nathan Portlock, and Miguel Sanchez-Enkerlin.

By concentrating businesses and errands, the switch can also be a real estate organ capable of providing revenues to augment the now uncertain public funds for transportation. With real estate revenues from its train stations, Japan Rail for instance has been able to impeccably maintain and upgrade its system while also funding research and development in technologies like Maglev. Transit organizations are sitting on large amounts of land that is only used for parking, but AVs require much less space than privately owned cars. Transit stations make some money from parking, but if that space can be converted to the space of a switch and filled with retail and business opportunities, it can return much larger revenues to support both local and transportation innovations of all sorts.

The switch might also address issues to do with employment and cultural divides caused by poverty or racism. Transit systems are typically routed to serve more affluent neighborhoods, meaning that travel times for those who live in poorer areas are too long on a good day and impossible on a day with other difficulties. But AVs can travel anywhere, and the switch can be a place for the cultural mixtures that generate diversity as well as social and economic cohesion. Even now, the routines of the switch can be rehearsed with the vehicle fleets of the ridesharing economy with the view to better transitioning employment once cars are fully automated. The switch may be a place to organize that transition, since its concentration of businesses and services is a source of potential jobs to compensate for those lost in the taxi and ridesharing businesses.

The switch is not another utopian proposal. It is an idea that could be gamed and exploited in ways that destroy it, and in the US, cars can perhaps only be pried from the cold dead hands of their owners. There is a good chance that the advent of AVs could simply lead to the next transportation catastrophe, or to mobility companies organized as monopolies with bullet-proof accumulations of power and information. But maybe the idea of the switch simply represents a shift in habit of mind or a shift of the essential disposition of power in cities—a sense that there is more information, choice, and equity for more people when there is an interplay between digital, spatial, and human networks. It is a disposition that hopes to benefit many by including many.

The switch might then encourage a different, impure approach to political activism. An activist can righteously fight against attitudes about energy and mobility in the US by protesting against environmental deregulation, fighting for a retightening of things like Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards or working to establish alternative renewable energy sources. Or the switch could be a social prescription of well-meaning urbanists bent on “transit-oriented development” (if the association with markets and real estate was not already too tainted for the purist). But these sorts of approaches have little chance of outwitting the current political climate and mitigating against our transportation stupidities.

When thinking about not only a single new technology but the mixing chamber for many technologies, an architect can design volumes with shapes and outlines as well as the spatial and cultural medium in which they are suspended. Since there is hardly any hope of making a system shift like the switch without also being able to manage the spin that surrounds it, this medium design works on many networks simultaneously. It shifts potential in a matrix with instructions and specifications for an architectural proposal, but it also crafts the promotional stories that attend the idea. Those stories are not an end in themselves, but rather a deliberate instrument to manipulate habits and routines in a way that has measurable spatial consequences.

And since the messages of car commercials have managed to create a contagion that has utterly changed the urban landscape with a desire, maybe a contagious story about the switch might travel under the radar and galvanize developments around alternative political and environmental alignments. It would be a good trick if designers somehow directed the next wave of cloying soft focus commercials for, not cars, but mobility companies. While having to stop and change modes of transportation would ordinarily be regarded as an disruption to the dream of seamless travel, these ads would promote another dream in which the switch is portrayed as the new marker of luxury, elegance and freedom.

Large amounts of land previously used for parking and automobile traffic could be liberated to be either developed or used as leisure spaces. The urban landscape takes on a new morphology that encourages walking, running and biking. Image: Brian Cash, Dan Glick-Unterman, Nathan Portlock, and Miguel Sanchez-Enkerlin.

In thirty seconds, an ad might show a single parent household with a two-year-old and babysitter at home and a teenager in school. On a bad day when the babysitter has to go home early, she takes an AV to the switch, waits for the teenager’s soccer team to be delivered, places baby brother in big brother’s care, before running to catch a train. With baby brother on his shoulders, big brother waits for Mom’s train while winning approving looks from other teenage girls. When a relieved Mom joyously arrives, all three pass through the glorious voluminous space of the switch. There are other parents in the background picking up from daycare and escorting children dressed in Karate uniforms or carrying violin cases. Given that AVs provide access for many neighborhoods, including those which might have previously been without mobility, the crowd in the switch is diverse. The three shop for dinner in the market, and then get into an AV in the queue that is picking up departures. In the background, others are getting onto bicycles or beginning a jog for the last mile home. Maybe in the distant background of the shot there is even a city that no longer has parking spaces. On their way home, teenage brother plugs in his iPhone and blasts his music while a super cool hands-free Mom, now facing her children instead of the road, juggles oranges from the grocery bag.

Another soft focus ad might feature the switch as a new micro-institution in suburban neighborhoods. In places where there are no trains or in any neighborhood that wants to aggregate riders for AV pooling, there might be a small switch within walking, running, or biking distance to many surrounding homes. It has a monitored waiting station for travel to and from school, and it is the place where everyone gets their AV to go to work or to a larger switch that has a train. It has bike storage and changing rooms, but it might also have daycare, food stalls, farmer’s markets, exercise classes, or workspaces. This ad would show Dad returning from work to the switch. While picking up his child from the daycare, he hears someone call to him. Mom has just arrived and signals that she is going to change into her running clothes. Dad hurriedly buys dinner and gets to the bike racks. The next bit of advertising cuteness shows Dad cycling home with the child in a front carriage while a jogging Mom challenges them to a race. Merging the sexiness of ads for running shoes with ads for mobility, exertion has become the new luxury.

The wholesomeness continues. The landscape they are moving through has a very different morphology. Because there is a nearby switch there is really no need for the forty to sixty-foot wide roadway onto which the suburban house usually fronts. Nor is there a need for garages. Just as the car was a contagion that inflated distances in the twentieth century suburb, now the AV contracts those distances and replaces them with greater density or more collective landscapes like parks or—if the ad is especially trendy—the newest forms of suburban agriculture.

However impure, promoting stories about switching or interplay might be a sly form of activism, but one with the capacity to have compounding effects on energy, the environment, mobility, and settlement patterns. With political superbugs, whether they are car companies, oil conglomerates, or presidents, earnest proposals can be ineffective and direct opposition sometimes only delivers the nourishing rancor that fuels a fight. But the switch satisfies the desire for market incentives before these powers have a chance to politicize them, and the superbugs themselves are abundant proof of the power of stories to bend steel and buckle concrete. If it is better to keep the power players guessing, the switch might be a cunning way of shifting the ground at a precarious political juncture.

Lawrence D. Burns, William C. Jordan, and Bonnie A. Scarborough, “Transforming Personal Mobility,” The Earth Institute Columbia University (August 10, 2012), ➝. The term “Mobility Internet” was first coined in William J. Mitchell, Christorpher Borroni-Bird, and Lawrence D. Burns, Reinventing the Automobile: Personal Urban Mobility for the 21st Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010).

Matthew Claudel and Carlo Ratti, “Full speed ahead: How the driverless car could transform cities,” McKinsey & Company (August 2015) ➝.

Ibid., Burns, Jordan, and Scarborough.

Autonomous Vehicle Technology: A guide for policy makers, RAND, 2016. See also ➝.

Keller Easterling, Organization Space: Landscapes, Highways and Houses in America (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999).

Viodi, “Self Driving versus Driverless - A Mobility Update with Alain Kornhauser #CES2107”, YouTube (March 10, 2017) ➝.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

Positions is an initiative by e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)