Many have claimed that we are witnessing an end of architectural theory, the replacement of theory with history, or simply an era of disunified and un-theorizable practice; that the conditions that made architecture into a particularly deep bathing pool of ideas are no longer. If the basis for comparison is, say, architectural culture in the US during the last decades of the previous millennium, it might appear that architectural ideas have sloshed out of the pool and onto the field itself, and then you could pick your metaphor: they evaporated into irrelevance; etched deep ruts of thought; or washed out new ideas. We could perhaps blame technical disruption, the shifting foundations of disciplinary institutions, and the unpredictable tremors of capitalism.

Instead, we should interrogate these anxieties, and ask why we need a single theoretical project or debate in architecture. If we multiply our lenses for what counts as theory, we can recognize the ways in which theories abound, inside and alongside practice, and outside of the geographic and cultural constrictions of European and North American architectural thought. We can acknowledge the need for provisional intellectual autonomies within history and theory, as well as for the ties that bind it to practice and the world at large. We can think together about how to write history and theory (or maybe just take breaks for urgent political action!) at a time when the crises of climate change, dis-inclusion, and de-democratization demand our attention. And, for all its problems, we can also celebrate the presence of theory and history in our field, which when entwined in the particular way of our discipline, offers a vital model of praxis missing in professional education in science, engineering, and law.

Importing

Architectural theory in the United States has been provincial: a situated and specific form of knowledge produced in particular parts of the world by selected members of the discipline. Yet its foundations are not intellectually hermetic; over the last fifty years, architectural historians and theorists working in universities in the US (who were often originally practitioners) have substantiated their work with discourses and disciplines “imported” from outside of the history and theory of architecture. If we examine the journal Oppositions, whose editors became key protagonists in East Coast architecture schools, we see that so-called “critical theory” from outside of the disciplinary history of architecture—mainly that of the Frankfurt School and French deconstructionists—was frequently cited and then reinterpreted in order to define and ground strains of architectural practice.1 Intellectual hospitality towards other disciplines helped bring architecture into dialogue with other fields, and to certify that a form of criticality mostly generated from within the discipline was, in fact, part of a larger critical project spanning disciplines and continents.

This practice of import, which aligned with architecture’s “high theory” moment in the United States, helped to create an academic practice of architecture. Yoking architectural theory to other theories made the history and theory of architecture legible as part of the humanities. University PhD programs in history and theory of architecture within schools of architecture began in the 1960s, which in the following years led to the development of processes for tenuring faculty in architectural history that aligned with other tenure processes in the humanities.2 Professionalizing history and theory in this way has enabled at least a small economic diversification of the field; thanks to the university it is possible for a (far too small) number of us to work as architectural historians without the need for supplemental design practices or independent incomes. Intellectual hospitality to so-called “critical theory” in part enabled the professionalization of history and theory, and this professionalization is a precondition for some diversity of perspectives in our field. But it should be clear just how much more diversification of the profession and the professorate is still necessary.3

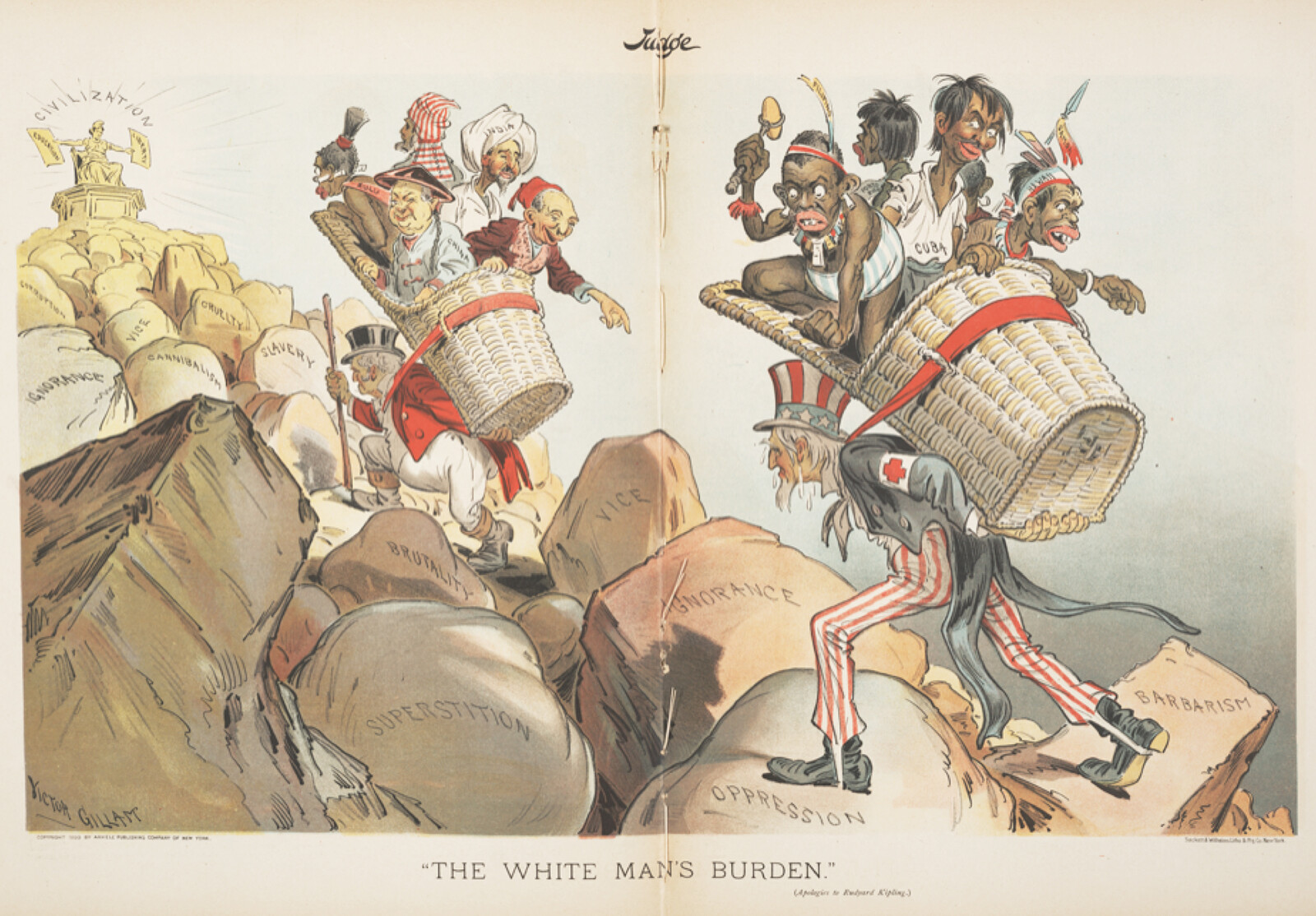

Even as it helped to found and enliven the discipline, we have to be careful not to romanticize architecture’s “high theory” moment. It was marred by pernicious forms of sexism and racism, not to mention misreadings and selective appropriations. For instance, Jacques Derrida’s ideas inspired many architectural projects, but his work on the ethics of translation and (later) on hospitality were largely ignored within practice. Later, Gilles Deleuze’s writing was used to justify blobby forms, but only theorists seemed to care about his ideas about anti-fascist micropolitics. Too many thinkers whose writing and activism transformed the humanities—Gayatri Spivak is a primary example—were taken up by architectural historians and theorists, but not mediatized in journals of practice. Today, we need historians and theorists to engage ideas from both inside and outside of the field. This will help us to develop more rigorous notions of what architecture does when it encounters the world, and to more deeply decolonize architectural thought. While the politics of import are never neutral, and the codes of hospitality are difficult to navigate, North American schools of architecture also need theories which have not registered within our canons so that we have other ways of interpreting and understanding architectural form, its place in the world, and its roles in the management of human and non-human life.

The continuing crises of misogyny and racism have prompted a resurgence of ethical thought around power and subjectivity in architecture. There are decolonial dissertations being defended every term, and newer groups like the Global Architectural History Teaching Collaborative (GAHTC) and the Feminist Art and Architecture Collaborative (FAAC) publish lectures and syllabi that support the teaching of histories of architecture that do not begin and end with the work of European men.4 Architectural historians and theorists now engage Donna Haraway’s cthulucenes, Elizabeth Povinelli’s geontologies, and Anna Tsing’s mushroom worlds as they research the discipline’s production of the climate crisis. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectional understandings of race, sex, ethnicity, and gender are rethought in crucial new work on the production of these categories in and by modern architecture.5 This is accomplished through historical research, but also in the documentation of contemporary architectures, infrastructures, and logistics with techniques specific to the discipline of architecture. New work on how materials circulate, how buildings are funded and commissioned, how they do and don’t participate in specific forms of statecraft and subjectivity production, and the roles people long excluded from narratives of architectural history have played in the shaping of the built world are essential.6 Of course, not all histories and theories of architecture must take it upon themselves to transform politics, and presentisim is most powerful when it is tactical and selective. But these new projects give hope that the field is changing, and that handing off institutional power to a new generation of thinkers might bring us into a theory-history moment both more inventive and rigorous than any we’ve encountered yet.

In my view, we do not need to de-academicize architectural history and theory; we just need more of it, and better working conditions for scholars, especially in the early phases of their careers. We also need academic specialization: the specific forms of knowledge making, writing, questions about narrative, evidence, and methodology necessary for writing history worth reading. We need tenure lines for young scholars, and new tenure rules that allow these scholars to solidify emerging methodologies. In certain cases, architectural historians now have the institutional standing necessary to shape these tenure requirements, to make them more specific to the varied discursive and visual practices of our emerging discipline. Yet sadly, only a few forward-thinking academic institutions give tenure credit for public history, criticism, exhibition practice, editorial labor, or other work directed towards practitioners and the world outside the discipline, which means that most people without tenure must do this work on borrowed time, or not at all.

Absorbing

As a field, we can certainly do more to make the feedback loops between theory, history, and practice stronger, but compared to other fields, I would argue that we are extremely lucky. Praxis is, even if imperfectly, still institutionalized in our discipline. The US National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) mandates global history and theory courses for architects seeking licensure. Being in the same building, sharing lecture series and academic deans, sitting in on crits, as well as our shared little magazines, podcasts, academic conferences, and journals offers historians, theorists, and designers proximity, collegiality, and often a shared vocabulary. This does not mean that there are not abundant, and sometimes humorous mistranslations between these subfields. But the fact that we have institutional apparatuses for connecting the world of theory to the world of design is remarkable.

We should tend to these apparatuses. Doing so also means attending to the cultures of overwork in schools of architecture. No one can make sense of an unfamiliar history or theory on two hours of sleep; no one can dream up a new theory when she hasn’t left her desk in a day. The same NAAB that mandates history and theory demands a slew of other courses, and both educators and the larger economies in which we work offer our students too little time for reflection, speculation, and especially political action. This is particularly the case for students grappling with new languages or performing extensive paid labor or unpaid care work. These are students whose perspectives we desperately need in our field. As the Architecture Lobby and others have clarified, combatting overwork requires resisting precariousness in design practice, but also in the professorate. Essayist Will Glovinsky recently noted that in the US there are more casual academic workers than coal miners.7 Hasn’t history and theory taught us to organize?

Exporting

We could contrast this history of reflective practice that is deeply embedded into architectural education with that of other professional fields in universities, such as law or engineering. Both of these fields have separate disciplines—Critical Legal Studies, and Science and Technology Studies (STS)—that historicize and criticize the grounds of these fields of knowledge. The insights and criticisms of STS toward the practice of science and engineering are often taken up in architectural scholarship, but they sadly do not always reach scientific practitioners. Indeed, only a few pioneering engineering schools have embedded STS programs; aside from general distribution requirements, most in STEM fields have no disciplinary history, theory, or even ethics requirements they must fulfill. A recent attempt to celebrate the engineering programs that do pair reflective concept acquisition and critical engagement with the history of science in a recent issue of the online journal IEEE Spectrum was met with angry panning.8 Commenters—who seemed to have little idea what STS courses actually do, and what STS research produces—parodied the idea that they would be made to question why they might do their work, belittling STS as a meaningless occupation for those who couldn’t hack scientific practice. Architecture students may not always love their history classes, and the specialist obsessions of theorists and historians can be met with bafflement, but this kind of hostility is difficult to imagine in our field.

The shared space between architectural historians, theorists, and designers within academic institutions entangles us in ways that other critical fields must envy, and in ways that at least has some potential to nourish criticality and ethics within practice. Can you imagine the kind of avant-garde, counter-capitalist software or experimental interfaces we might have if all software architects were required to understand the history of their discipline and the ethical stakes of their work? Would an engineering avant-garde make self-crashing cars, or data brokers remake the financial markets by assigning credit randomly? No doubt we would duplicate many of the problems of design avant-gardes in late capitalism that architectural historians have long excavated. But I think we might end up with a slightly less frightening world. Without romanticizing our present situation, we can nonetheless celebrate the conceptual and ethical rigor of the histories and theories of our discipline. We’ll continue our import practices, borrowing and transforming theories from across the humanities. But we should also talk about exporting: not only our research insights, but our unique institutional and pedagogical formations.

See Meredith TenHoor, “Oppositions” Pidgin 3, Fall 2007.

This was the topic of a 2005 conference at Princeton University, “Discipline Building,” organized by Beatriz Colomina, Annmarie Brennan, Michael Wen-Sen Su, Shundana Yusaf and myself.

This is clear from looking at NCARB’s data on the profession at large; see ➝. See also Lian Chikako Chang, “Where are the Women? Measuring Progress on Gender in Architecture.” Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture website, October 2014, ➝; Héctor Tarrido-Picart, “Valuing Black Lives Means Changing the Curricula,” The Aggregate website, Volume 2, March, 2015, ➝; and Jonathan Massey, “How can architects build the equitable discipline we deserve?” Architects’ Newspaper, September 20, 2018, ➝.

It is worth noting the funding discrepancies between these two projects; GAHTC has been admirably and importantly supported by funds from the Mellon Foundation. While FAAC is a newer initiative run by much younger scholars, I yearn for the day when foundations support feminist scholarship with this kind of commitment.

See especially the “Race in Modern Architecture” project and forthcoming book edited by Irene Cheng, Charles Davis II, and Mabel O. Wilson.

See for instance the articles in the special section of Architectural Theory Review edited by Ana María Leon, and Niko Vicario, “Designing Commodity Cultures,” Architectural Theory Review 21, no. 3 (September 1, 2016): 277–279; and the recent work of Ateya Khorakiwala on material circulations. I also see the championing of this form of history to have been a project of Aggregate. In my own teaching, I’ve leaned on Mark Jarzombek’s discussions of agriculture and irrigation, which has helped me to trace long urban histories of biopower; on Adedoyin Teriba’s work on how practices of building established untheorized aesthetic exchanges between Brazil and West Africa and Ayala Levin’s on the connections between West Africa and Israel; on Felicity Scott’s excavations of the geopolitics in avant-garde practices; on Helen Gyger’s work on housing production in Peru; on the analyses of labor that the Who Builds your Architecture? group has done, as well as those of the Architecture Lobby; on Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi’s work on migration; on the writings and discussions in Aggregate’s workshops, and on so many others I do not have room to mention here.

Will Glovinsky, “The Great Global Grad School Novel.” Public Books blog, October 22, 2018, ➝, citing March 2018 statistics from the US Department of Labor.

See Susan Hassler, “STEM Crisis? What About the STS Crisis?” IEEE Spectrum, Sept 21, 2016, ➝.

History/Theory is a collaboration between the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich and e-flux Architecture.