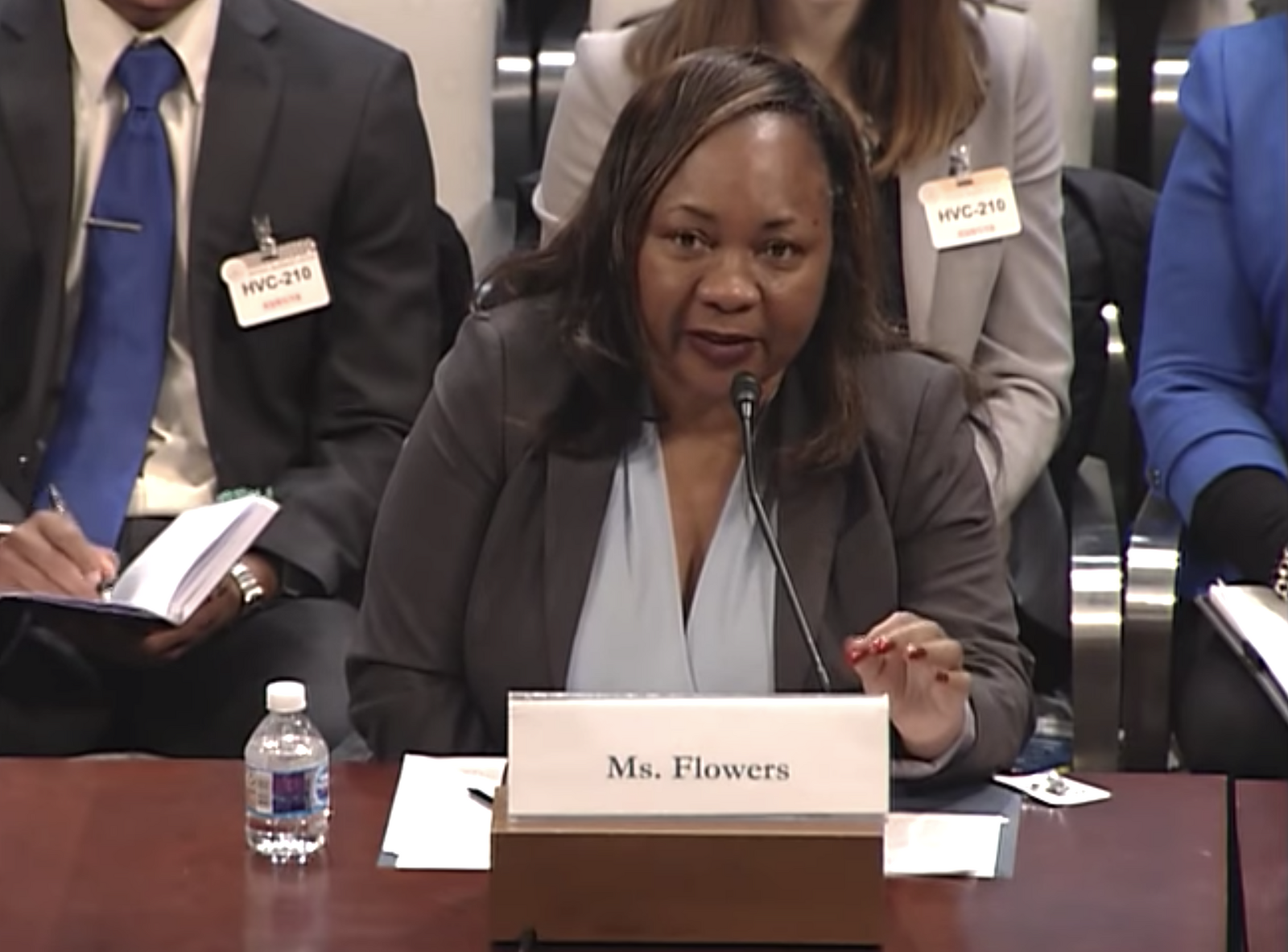

To the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

Subcommittee on Water Resources and Environment

Thank you, Chairwoman Napolitano, Ranking Member Westerman, and all of the members of the committee for the opportunity to testify. My name is Catherine Coleman Flowers. I am the rural development manager for the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama. I also serve as practitioner in residence at the Franklin Humanities Institute at Duke University, a senior fellow at the Center for Earth Ethics, and I am the founder of the Alabama Center for Rural Enterprise, which has a mission of targeting the root causes of poverty.

I am a country girl, having grown up in Lowndes County, Alabama. Lowndes County is located along the historic voting rights trail from Selma to Montgomery. As a child, I used an outhouse and slop jars. My family eventually installed a cesspool which facilitated us having functioning indoor plumbing. When I left the county and returned later, I was surprised at the disparities that existed in wastewater treatment. In 2002, I invited Robert Woodson of the National Center for Neighborhood Enterprise to Lowndes County to see firsthand the problems residents were experiencing. A County commission asked us to alter our trip to visit the home of a family that was threatened with arrest for having a failing septic system.1 As we approached the home, we could see raw sewage running down the road from the septic tank. A man approached us as we were walking up the road, crying. He had been threatened with arrest and was told he could no longer hold worship services at his church because he did not have a septic tank. Mr. Woodson called William Raspberry from the Washington Post who wrote a column about the arrests, which was the first time that I can recall there being any media attention regarding this problem.2 These arrests have since decreased, but the threat remains.

The “black belt” region of Alabama, where Lowndes County is located, is particularly affected by the lack of adequate sanitation services because of its clay-like soil, which worked well for growing cotton during the slavery and sharecropping eras, but makes it extremely difficult to install and operate septic systems. Due to these inadequately porous “drainfields,” over half of the region is unsuitable for conventional septic systems, meaning that failing septic tanks are common.3 Most of the soil in Lowndes County requires a more complex type of system, which can cost up to $30,000.4 Yet the median household income in Lowndes County was only $27,000 in 2016, making more costly systems out of reach for most, and leading people to rely on unpermitted systems after their septic tanks repeatedly fail.5 Families that cannot afford to install septic systems must use some alternative method to dispose of waste without treatment, such as a straight pipe. Straight pipes are generally metal or PVC pipes connected to a home’s plumbing that discharge raw, untreated sewage directly to yards, ditches, woods, or various surface waters. In 2011, the Alabama Department of Public Health estimated that in Lowndes County, forty to ninety percent of homes have either no septic system or an inadequate one, and fifty percent of the septic systems people do have are failing.6

Initially, we were told by Health Department officials that the problem was that poor families in Lowndes County could not afford the expensive engineered systems needed to treat wastewater on-site in Black Belt soils. However, we began to discover that was only part of the issue when a member of the community approached me and said he could afford any system, yet he could not find one that actually worked. I quickly learned that the problem is much larger than just failing septic tanks and straight piping. Since 2002, I have visited homes where, each time it rains, sewage comes back into the house through either the toilet, bathtub, or both.7 In one town, citizens pay a wastewater treatment fee to a management entity, yet they still have sewage backing up into their homes and yards. One neighborhood in another town is bordered by a sewage lagoon which is full of raw sewage piped there from residents’ septic tanks. In addition to the stench from the lagoon, their tanks must be pumped as often as three times a week to remove sewage from their yards or their homes.

Charlie Mae Holcombe, a resident of Lowndes County, recently told former Vice President Al Gore and Bishop William Barber about the problem she has experienced for more than twenty years.8 Holcombe can’t let her grandchildren play outside due to the sewage outside their home, and has had to replace her carpet countless times after sewage has run into the house. The families I speak to, including Mrs. Holcombe’s, also regularly complain about illnesses. Living with repeated exposure to raw sewage causes acute and chronic health impacts and reduces families’ standard of living. Short-term exposure to parasites, bacteria, and viruses in raw sewage can cause infections or diarrhea and have also been linked with long-term health impacts such as cancer, dementia, and diabetes.9

With longer periods of warm weather, mosquitoes are more common in the fall and winter months. In October of 2009, I was asked by State of Alabama Health Department officials to meet them at the home of a pregnant woman who was threatened with arrest for not having a septic system. She lived in a singlewide mobile home. Behind her home was a pool of raw sewage that ran into a pit. It was teeming with mosquitoes, and I was bitten all over my legs. Shortly thereafter, my body broke out in a rash. Seeking medical care, my blood tests came back negative for known diseases, providing no clue for the raised rash that covered most of the trunk of my body and was sporadically on my legs and arms. That was when I asked if it was possible that I had something American doctors were not trained to look for.

The conditions in Lowndes County are not what many people expect to see in the United States. Problems occurring in rural communities are far from the major media centers and often go unnoticed. In August of 2012, I read an op-ed in The New York Times written by Dr. Peter Hotez, the founding dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor’s School of Medicine, entitled, “Tropical Diseases: The New Plague of Poverty.”10 We met a brief time later and from these meetings, came up with the idea to look for hookworm and other tropical parasites (which were long thought to have been eradicated from the US) in stool samples, soil samples, water samples, and blood samples in Lowndes County. In September of 2017, our peer-reviewed study was published. The study found that thirty-four-and-a-half percent of participants tested positive for hookworm and other tropical parasites in Lowndes County.11 Hookworms are not deadly, but they can cause delays in physical and cognitive development in children.

What we concluded is that in many instances, onsite septic systems and some “package” treatment systems were not working correctly, even after large expenditures by homeowners, and that cheap lagoon systems are generally used in poorer or more rural communities. This is not just a Lowndes County or an Alabama problem. I have heard of examples of these type of failures throughout the United States. For example, in South Florida, more and more septic systems are vulnerable to failure due to climate change. A recent study has found that by 2040, due to sea level rise, sixty-four percent of Miami-Dade County’s septic systems could harm people’s health and water supply.12

It is estimated that more than twenty percent of the country uses onsite wastewater treatment, and this percentage reaches forty percent or more in some states with large rural populations like North Carolina, Kentucky, South Carolina, Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire.13 Up to half of conventional septic systems in the US function improperly or fail completely at some point in their expected lifetime. By some estimates, sixty-five percent of the land in the US cannot support conventional septic systems.14

In December 2017, Philip Alston, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights visited Lowndes County at my invitation, as part of a tour of the US. In a statement, he noted: “In Alabama, I saw various houses in rural areas that were surrounded by cesspools of sewage that flowed out of broken or non-existent septic systems. The State Health Department had no idea of how many households exist in these conditions, despite the grave health consequences. Nor did they have any plan to find out, or devise a plan to do something about it.”15 The nonprofit organization I founded, Alabama Center for Rural Enterprise, has since filed a Title VI complaint with the Department of Health and Human Services, alleging that the Alabama Department of Public Health and Lowndes County Health Department have, for decades, been causing an adverse impact on the health and well-being of the black community of Lowndes County by failing to address this problem. The Department of Health and Human Services is currently deciding whether to investigate this complaint.

It is time for Congress to act to address this widespread problem that rural communities across the country face. In order to meaningfully address the issue of inadequate onsite wastewater treatment, a comprehensive approach must be taken.

As a baseline, there needs to be an acknowledgement of this problem more broadly. It has only been recently that we have begun to garner attention in the media about the lack of adequate wastewater options for some communities, but for years Lowndes County residents largely suffered in silence, and many across the country continue to do so. Members of Congress should talk to their rural constituents to find out where adequate wastewater services may be lacking in their districts.

Local, state, and federal authorities also need to eliminate laws, policies, and practices that criminalize residents for their failure to comply with wastewater regulations, even when the cost to do so is substantially higher than their means.

We need more information on where people are living without access to sanitation and wastewater services, as well as on individuals who pay a wastewater treatment fee to a management entity and yet still have sewage backing up into their homes. The Rural Community Assistance Partnership estimated that more than 1.7 million people in the United States lack access to basic plumbing facilities,16 and the EPA estimates that more than one in five families in the US are served by decentralized wastewater.17 This is only an estimate, however, as most states do not have an inventory of where septic systems are located. The US Census once captured information regarding whether homeowners were served by municipal treatment or septic systems, but the question regarding household sewage treatment was taken off after the 1990 census. As a first step, that question should be added back to the Census to begin compiling data once again to illustrate the scope of this problem.

Congress should use its oversight powers to ensure that investments are meaningful, that they are distributed equitably, and that agencies and engineers approving the use of the funds are ultimately accountable if a system fails. Funding should take into account the realities of climate change, as more rainfall and extreme weather due to climate change is likely to further stress these already vulnerable systems. It should also take into account community input and the unique geography of an area. For example, the soil in Lowndes County and across the Black Belt creates specific challenges that other communities may not face. Funding should go to those who need it most and cannot afford wastewater services or upgrades without assistance. And finally, Congress should ensure that individual homeowners are not responsible if the system that was approved for installment on their property, especially one that is installed using federal funds, fails due to the geography, soil, or other conditions outside of their control.

The Clean Water State Revolving Fund is an excellent tool to help communities with much-needed wastewater upgrades, but to be the most effective it needs the flexibility to reach the people who need it most.18

Although addressing the problem of inadequate wastewater and its roots in poverty and oppressive policies is complex, it must be done. Congress must begin this task now, while also researching new technological solutions for the future. This is an opportunity to remove the shame associated with discussing wastewater treatment failures and to instead focus on sustainable solutions that consider community input, offer assistance to those who need it most, and provide meaningful investment in wastewater that actually helps, rather than causes further harm.

In many states of the United States, it is illegal to either have no septic system or a failing one. In 2002, Alabama’s State Health Director stated that this problem was present in all sixty-seven counties in Alabama.

William Raspberry, “Civil Rights Failure,” The Washington Post, March 18, 2002, ➝.

United States Environmental Protection Agency, “How Your Septic System Works,” ➝.

Patricia Jones & Amber Moulton, “The Invisible Crisis: Water Unaffordability in the United States,” Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, May 2016, ➝.

“Lowndes County, AL,” Data USA, ➝.

Apple Loveless & Leslie Corcelli, Pipe Dreams: Advancing Sustainable Development in the United States, EPA Blog, March 5, 2015, ➝.

Some families have filed numerous insurance claims because of failed systems.

Khushbu Shah, “Al Gore admits US poverty ‘shocking’ – but warns climate crisis will make things worse,” The Guardian, February 22, 2019, ➝.

Jessica Lilly, Glynis Board, and Roxy Todd, “Inside Appalachia: Water in the Coalfields,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting, Jan 16, 2015, ➝.

Peter Hotez, “Tropical Diseases: The New Plague of Poverty,” New York Times, August 18, 2012, ➝.

Megan L. McKenna et al., “Human Intestinal Parasite Burden and Poor Sanitation in Rural Alabama,” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 97, no. 5 (September 2017), ➝.

Miami-Dade County Department of Regulatory & Economic Resources, Miami-Dade County Water and Sewer Department, and the Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County (Dr. Samir Elmir), “Septic Systems Vulnerable to Sea Level Rise,” (November 2018), ➝.

United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Septic Systems Overview,” ➝.

Richard Siddoway, “Alternative Onsite Sewage Disposal Technology: A Review,” Washington State Institute for Public Policy (January 1988), ➝.

Philip Alston, “Statement on Visit to the USA,” United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner, December 15, 2017, ➝.

Stephen Gasteyer and Rahul T. Vaswani, Still Living Without the Basics in the 21st Century: Analyzing the Availability of Water and Sanitation Services in the United States (Rural Community Assistance Partnership, 2004), ➝.

United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Septic Systems Overview,” ➝.

United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF),” ➝.

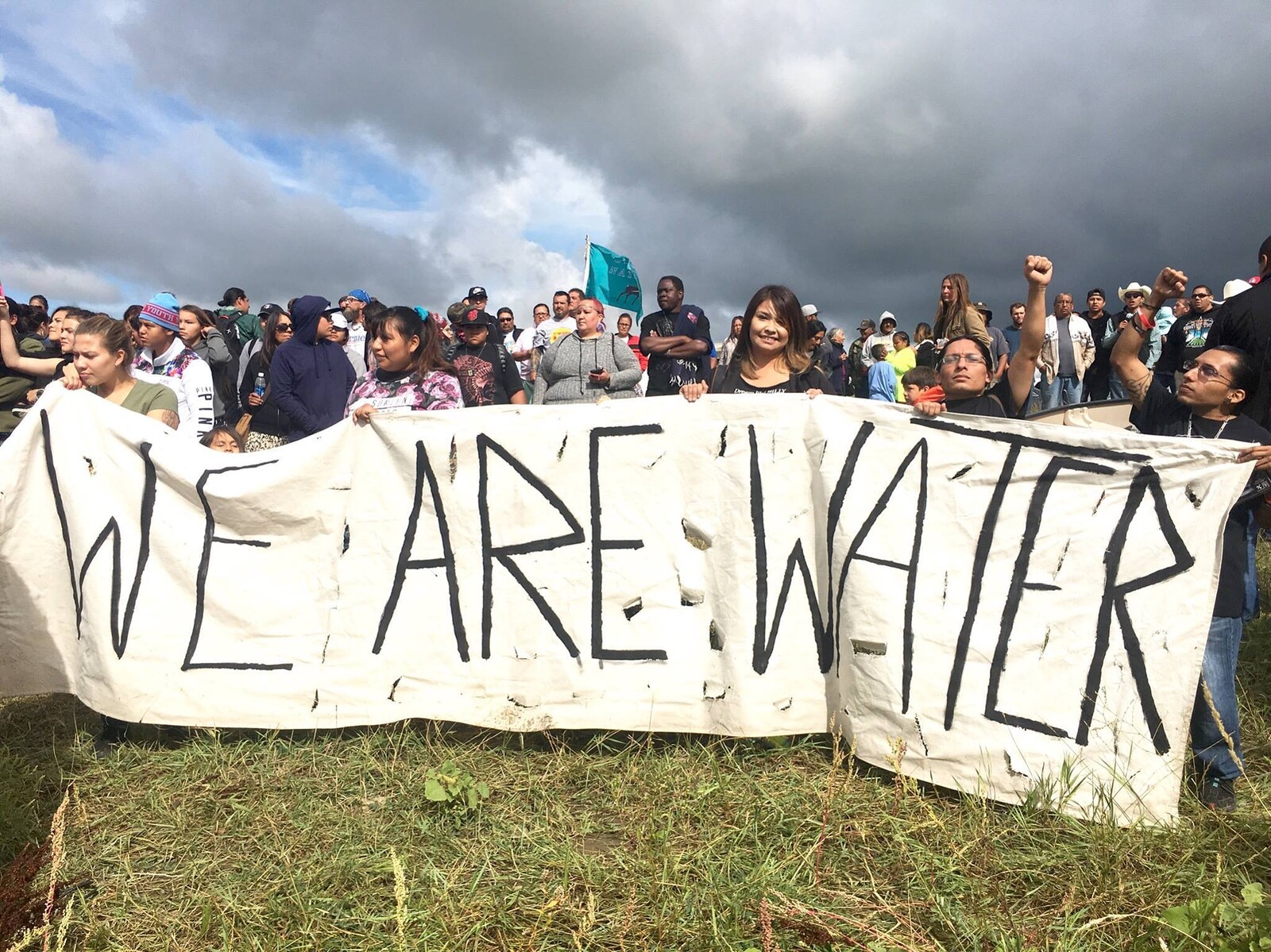

Liquid Utility is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture at Columbia University as part of their project “Power: Infrastructure in America.”

Category

This is an edited version of testimony that was delivered to the United States House Transportation Subcommittee on Water Resources and Environment on March 7, 2019.

Liquid Utility is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture at Columbia University as part of their project “Power: Infrastructure in America.”