“The difference between a good and a poor architect is that the poor architect succumbs to every temptation and the good one resists it.”

—Ludwig Wittgenstein

In the fall of 2017, I had the improbable pleasure of seeing two of the most important dwellings in the history of twentieth century philosophy in person within the space of a single week. (They do not exactly abut each other.) The first was the hut built by Elfride Heidegger (née Petri) in the early 1920s in the Black Forest village of Todtnauberg, for her husband philosopher Martin, on the occasion of his first professorial appointment at the University of Marburg. It is here that Heidegger hashed out the basic outlines of his magnum opus, Being and Time, published in 1927; it is in the rustic confines of this mountain cabin, rather than in the generic Nichts of his Freiburg villa, that he preferred to receive a steady stream of philosophical pilgrims and liked to be portrayed for posterity; it is this unassuming, unremarkable structure that has been made the subject of an entire architectural monograph—just recompense for a philosopher best remembered in architecture circles for having written an influential essay titled “Building Dwelling Thinking.”

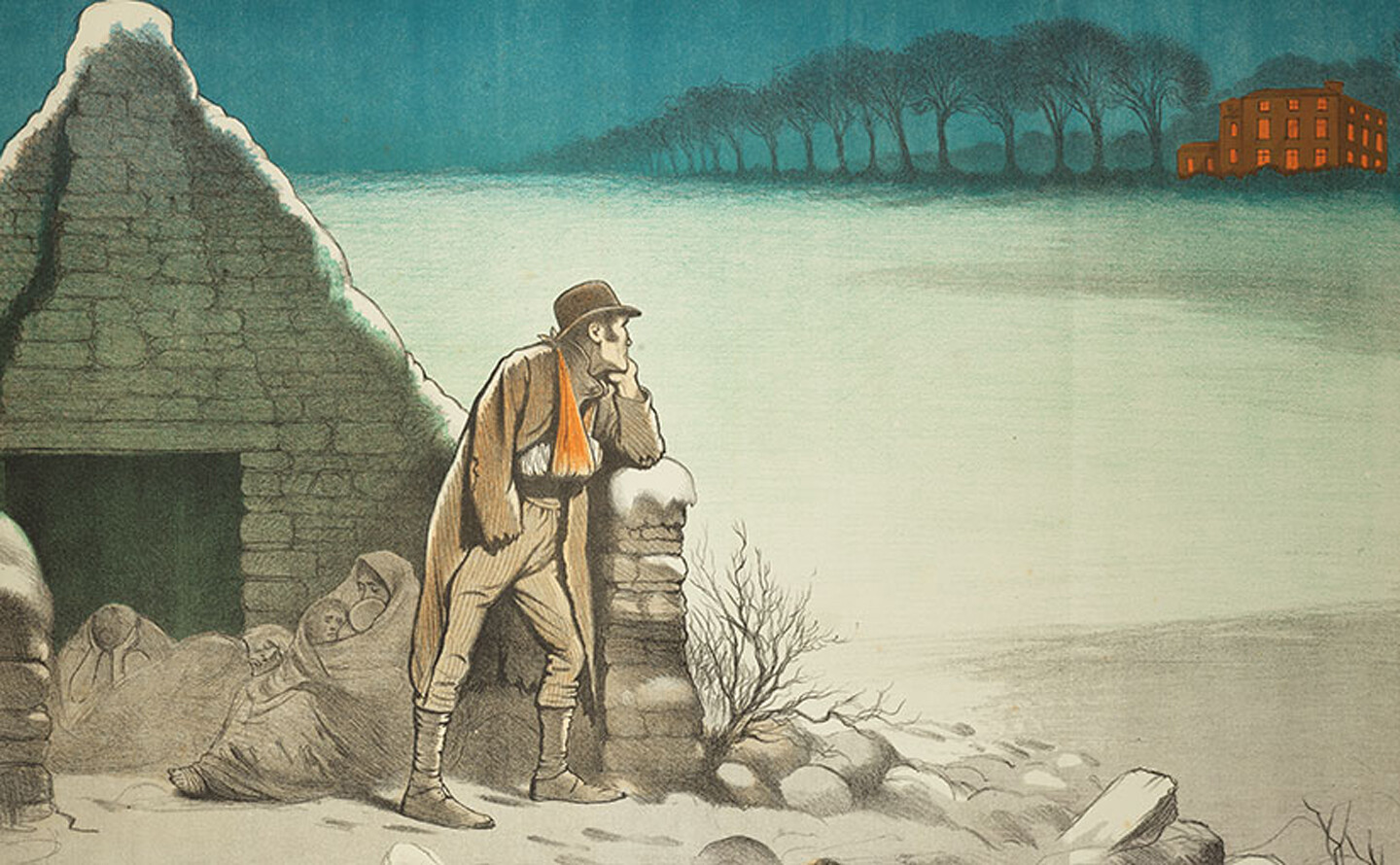

Heidegger’s hut is also famous for being hard to find and impossible to access: everywhere in the village of Todtnauberg there are signs pointing to the Heidegger Rundgang, but the exact location of the hut, sheltered from view by a clump of trees at the end of a Privatweg, remains an anxiously guarded family secret. You have to make your way past a trail of barbed wire to gain a view of the hut, whose perennially shuttered windows and front door whisper a unanimous verboten. The hut is still in the hands of the Heidegger family, who remain notoriously impervious to tourist entreaties of any kind, and the publication in 2014 of his Third Reich-era Black Notebooks has not simplified matters or otherwise helped clear the Schwarzwald air. The slight unease of the trespassing taboo notwithstanding, the overall impression of the hut is one of self-effacing Gemütlichkeit and ease: how cozy it is, up here in this bucolic pocket of southern Germany; how snugly must the fire crackle inside; how reinvigorating must the mulled wine taste after a day spent cross-country skiing outside.

The experience of visiting the site of the second dwelling, a mere four days after my jaunt through the undulating Swabian countryside, could not have been more different—and not just because, at the time of my visit, the actual hut was no longer there. Finding Heidegger’s cottage required no more than a forty-five-minute car ride east of Freiburg in a densely built-up pocket of the Eurozone. Seeing the remains of the second hut up close and in person required taking a small propeller plane from Oslo to the sparsely populated municipality of Sogndal, followed by another two-hour-plus drive along the longest and deepest fjord in Norway, and, finally, a hazardous climb up a steep rock path overlooking a small lake. The structure in question, long since vanished save for its square footprint hewn out of rock, once belonged to the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Wittgenstein first traveled to the remote Norwegian village of Skjolden, at the far end of the aforementioned Sognefjord, in the years shortly before the outbreak of World War I. He was in desperate search of relief from the oppressive niceties of Cambridge society life and in anxious pursuit of the solitude that would allow him to focus on revolutionizing the fundamentals of mathematical and philosophical logic—a task conclusively achieved, in his own immodest estimation (“I am … of the opinion that the problems have in essentials been finally solved”), in the pages of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, published in 1921. It is with the formulation of the basic outline of this landmark text in mind—more of a manifesto or prose-poem than a treatise—that Wittgenstein embarked on the project of building a hut of his own on a rocky outcrop overlooking Lake Eidsvatnet, located behind Skjolden proper. (This part of Skolden is still marked as “Østerrike” on some current maps of the region—in honor of their fabled Austrian guest.)

Reaching the hut back in the day when Wittgenstein made actual use of it—most crucially a handful of summers scattered across the 1920s and ‘30s, during which time he worked on what would later become known as his Philosophical Investigations—required rowing across the lake, and the only photograph in existence of Wittgenstein’s many sojourns in Norway shows him caught in that very act, oars in hand. In fact, anyone who has spent time thinking about this hut—perhaps some over-zealous architecture buff who was enchanted by Wittgenstein’s Tractatus in stone, the arch-modernist house he designed for his sister Gretl in Vienna in the late 1920s—will know that it is also famous for hardly having been photographed at all. There exist just two grainy black-and-white pictures of it, both taken from a hermit’s respectful distance. Wittgenstein had a notoriously low tolerance for even the most casual and accidental of intrusions—a site of pilgrimage this was certainly never meant to become. (No one knows what it looked like on the inside—how spartan, or how cushy.)

Apart from the sheer remoteness of the site, the contrast with Heidegger’s Black Forest abode could not be more glaring: it is simply inconceivable to imagine the ascetic, austere Wittgenstein posing for a photo shoot inside and around his Norwegian refuge the same way Heidegger so visibly enjoyed doing when visited, back in the late 1960s, by the German-Jewish photojournalist Digne Meller-Marcovicz. (Her photographs, meant to accompany a lengthy Der Spiegel interview that was only published after Heidegger’s death in 1976, remain the most exhaustive visual account of the sage’s monastic mannerisms.) Wittgenstein, in other words, was deadly serious about his self-imposed exile and need for escape—not the performing and/or staging of retreat as philosophical spectacle, one might say. (There is something immodest, however, about the hut’s decidedly theatrical location, so visibly aloof above the lake and attendant village life. The hut’s dramatic and spectacular isolation must have registered, to those in the know, as a statement or utterance—a properly deictic gesture, in the parlance of his philosophy of language.) This, in essence, is what the tale of these two huts boils down to: a matter of scenography.

When I visited the site of Wittgenstein’s hut on a rainy day (of course) in October 2017, my guide, Harald Vatne—Skjolden’s presiding historian and the driving force behind the decades-long, now-completed attempt to reconstruct the hut in its original location using original building materials—mentioned, as I was poking around the slippery, moss-covered perimeter stones, that just the week before he had taken a busload of some fifty Japanese tourists to see the exact same sight: a void. (Cue the inevitable philosophical platitudes of the “metaphysics of presence,” with echoes of the Tractatus’ infamous closing sentence “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”)

I first learned about this void sometime in the mid-2000s, when I came across a book titled, appositely, There Where You Are Not, a collaborative venture involving the Scottish artist-cum-poet Alec Finlay, the photographer Guy Moreton, and Michael Nedo, the long-time director of the Wittgenstein archive in Cambridge. Moreton’s photograph of the hut’s stone base amidst Norway’s lush mid-summer greenery perfectly captures the power of the lingering myth of the ever-searching, never-finding Viennese philosopher. Not only did it seem logical that the hut had long been gone, it also seemed just: the house that logic built, gone up in smoke.

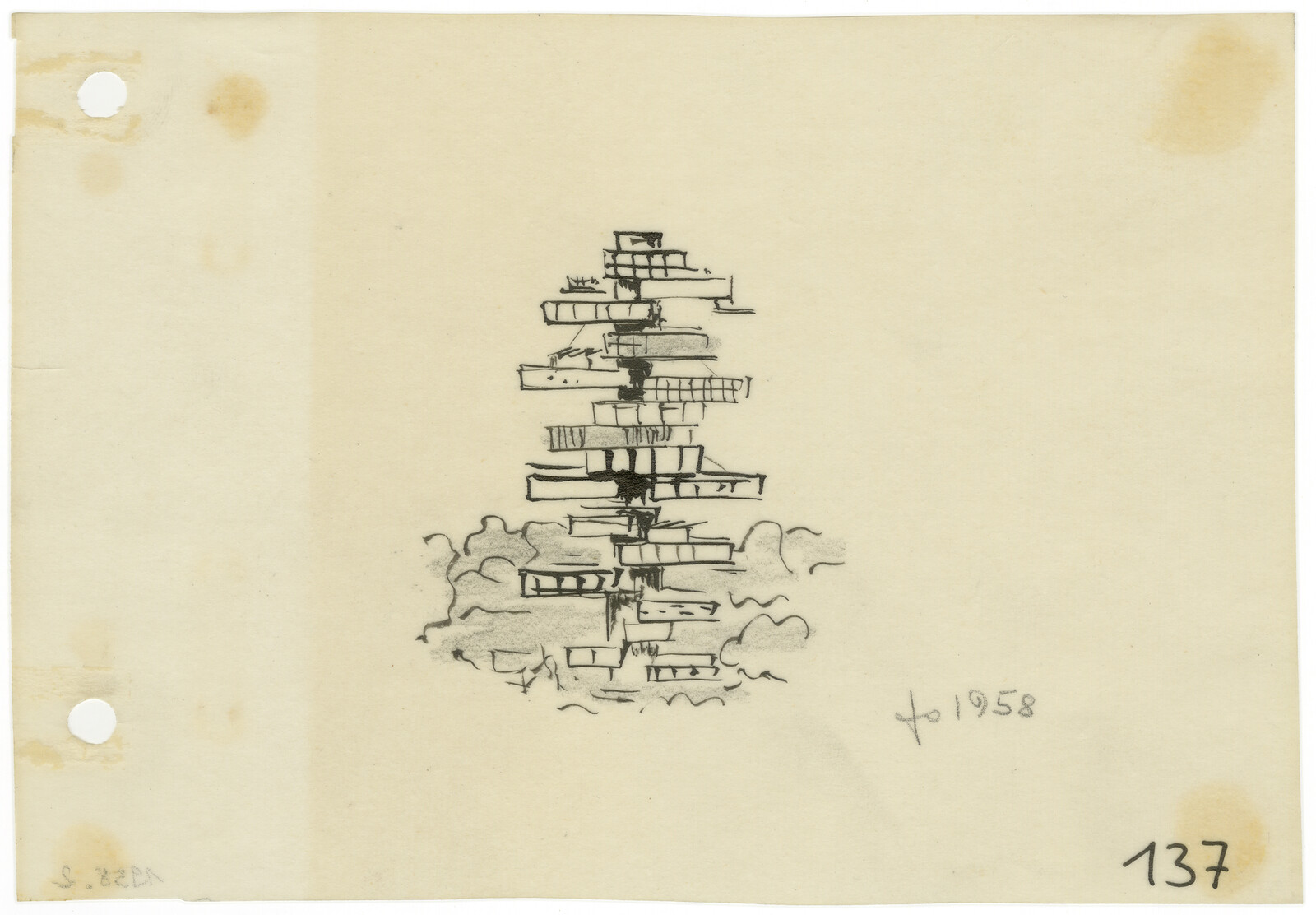

When Wittgenstein died in 1951—he last visited Skjolden in the autumn of 1950 but was already too frail to stay in the unheated mountain home—the hut came into the possession of a local family, who had it dismantled in 1958 and brought down the cliff using the same pulley system installed by Wittgenstein in 1921 for the collection of provisions. The philosopher’s hut was reassembled in the village center, where it stood, unrecognizable in its coarse cladding, for another fifty years or so. There, it had really become just a house, impossible to reconcile in the mind with anything even remotely Wittgensteinian. (This too must have seemed fitting at the time.) In 2009, however, it was once again taken apart, its components stored in two locations in the village (one being Harald Vatne’s garage), while its forlorn shadow on the clifftop across Lake Eidsvatnet gradually accrued a forbidding aura of the unspeakable (“Wovon man nicht sprechen kann …”). This aura is certain to become little more than a memory—and rapidly too—now that Wittgenstein’s hut has, finally and inevitably, been reconstructed on its original location, and will soon be open for regular (if philosophically-legitimate, of course) tourist business.

I have not made it back to Skjolden to inspect this new hut, though online images here and there do not disappoint in oozing naturel Nordic charm. One picture in particular reminded me of another Norwegian hut I had the privilege of visiting on another trip to (relatively) nearby Bergen, namely that of the composer Edvard Grieg—one of countless variations on the Nordic blueprint of the countryside cabin. (A four-hour drive from Skjolden in the direction of Oslo to the south will get you to the mountain hut of the late Norwegian eco-philosopher Arne Næss, whose retreat at Tvergastein has become something of a national shrine.) It would be a mark of poor taste, perhaps—and definite evidence of a decidedly non-Wittgensteinian streak of snobbery—to dismiss this eccentric attempt at expanding the arsenal of Norwegian tourist attractions as a blasphemous stain on the legacy of a philosopher notoriously obsessed with authentic living. Yet there is no denying that the innocuous silliness of this project—that is to say, the parochial scandal of the copy—helps shed substantial light on some of the more fundamental differences between Heidegger and Wittgenstein as basic philosophical temperaments, which do indeed revolve centrally, I believe, around the chimera of authenticity: as a quasi-theological category inauthentically lived (acted out, performed) in Heidegger, and as a paraphilosophical practice subtending, unwittingly, all of Wittgenstein.

When I first visited these huts in the fall of 2017, I did so in the service of curatorial research that culminated a year later in the exhibition Machines à Penser organized at the Fondazione Prada in Venice in conjunction with the city’s sixteenth architecture biennial. In focusing on the somewhat rarefied phenomenon of the philosopher’s hut (“who cares??”), the exhibition sought to explore the “correlation between conditions of exile, escape, and retreat, and physical or mental places which favor reflection, thought, and intellectual production.” (The exhibition’s pièce de resistance was a sculpture by the late Scottish conceptualist Ian Hamilton Finlay titled Adorno’s Hut.) A year later, the exhibition traveled on, in a radically compressed form, to the University of Chicago, where it was renamed HUTOPIA, and pondered “not just the matter of where thinking takes place, but above all, that of the three modes of productive disentanglement proposed by Wittgenstein’s Hut, Heidegger’s Hut, and Adorno’s Hut: respectively, the escape from the everyday pressures of hyperconnected urban life we all crave; the retreat we dream of; the exile we may find ourselves forced into.”

Although the relationship of the project to the tyranny of 24/7 connectivity always ensured a stable measure of relevance to broader cultural debates, there was an inevitable element of frivolity baked into the whole undertaking: a seeming paean to escapism as philosophical posture, this “hutopian” research was always going to be shadowed by the unsavory whiff of the ageing hippie “dropout” ethos, not to mention the atavistic luddite dream of the hermetic, monastic life. Heidegger’s hut: how corny, how petty; Wittgenstein’s hut: how arch, how prissy; how insufferably miserable, both! (There are obvious religious, or ecclesiastical, overtones to these architectural experiments in living philosophically. Heidegger grew up the son of a village parson and was destined to become a man of the cloth. Wittgenstein famously stated at one point that his thoughts are “one hundred percent Hebraic”; shortly before starting work on designing the Haus Wittgenstein for his sister, he worked as a gardener in the Brothers of Mercy monastery in Hütteldorf.) But here we are: thinking of philosophers’ huts—models of the primeval architecture of self-quarantining—in the shadow of a new imperative, that of social distancing. As in the restored view from Skjolden.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.