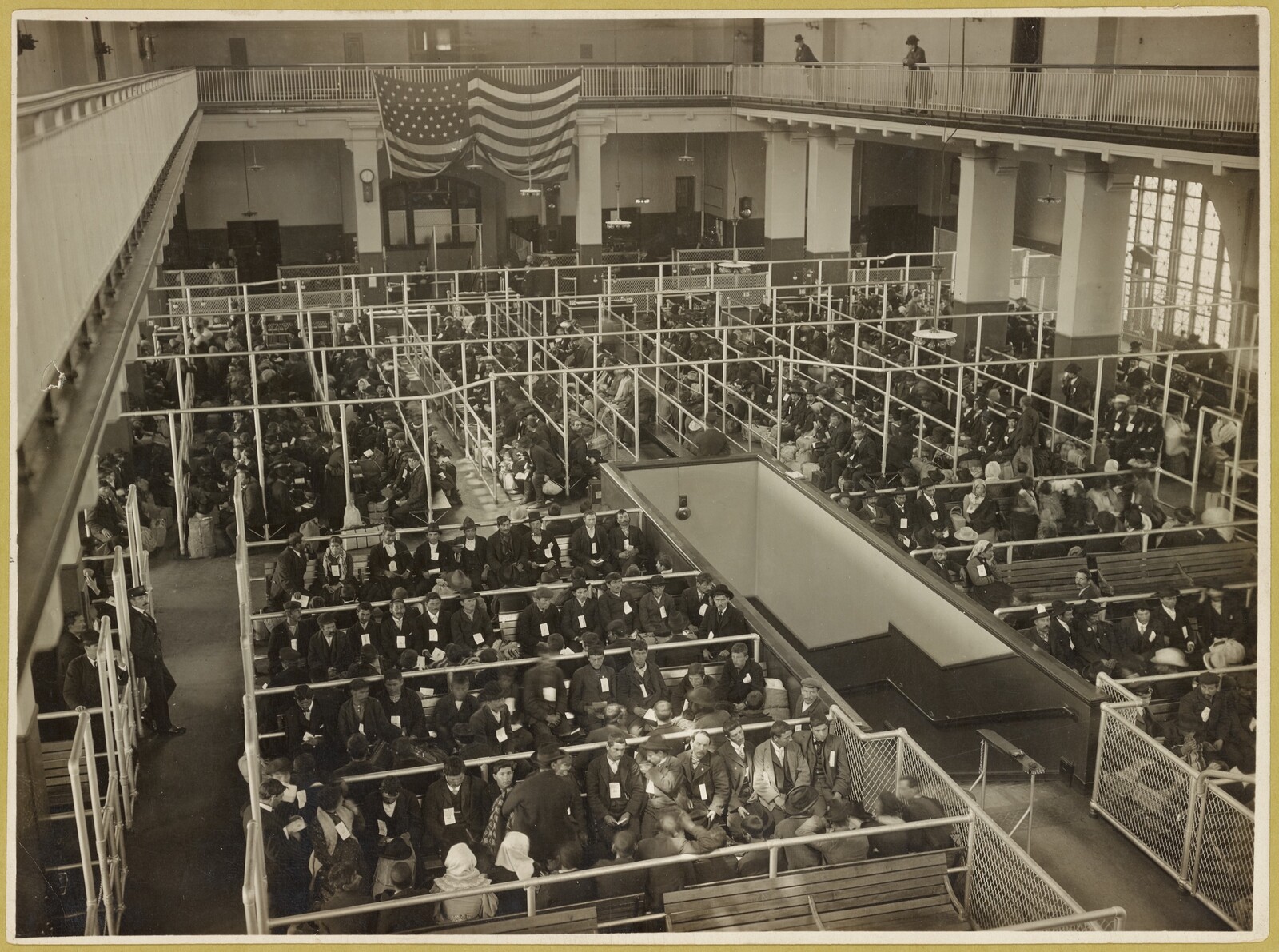

California and its northern population center, San Francisco, owes much of its character and development to disease. “Gold Fever,” as it was called, was undoubtedly the most powerful sickness to transform the small colonial village, Yerba Buena, into an international metropolis in less than a decade. The California Gold Rush (1848–1857) facilitated the largest recorded mass migration to a United States territory, with roughly 300,000 bodies descending upon northern California on their way to the goldfields, most passing through San Francisco.

Although gold fever provided the human capital to transform former satellite settlements of the Spanish and then Mexican empires, the human cargo also carried a vicious cocktail of old and new-world-diseases. While these pathogens found fertile breeding grounds in the filth emblematic of Gold-Rush-era San Francisco, disease would ultimately drive government institutions and immigrant communities to design semi-autonomous healthcare systems to primarily serve and support their constituents. In this sense, San Francisco’s first hospitals were not only early monuments of health, but the materialization of co-dependent social practices.

If the chaotic collection of dispersed, mobile, and ephemeral architecture was one of San Francisco’s first material expressions of gold fever, the establishment of modern hospitals can be imagined as the beginnings of an architectural cure. These hospital buildings, their origins, and their visual representations on city maps, postcards, and advertisements reflected and reified a particular social order that normalized the bodies and architectures of certain groups by stigmatizing the bodies and architectures of others. In other words, in an effort to control the spread of microscopic organisms yet to be called bacteria, an epidemic of racial prejudice and discrimination was transmitted and reproduced as a consequence.

From Gold Fever to Modern Hospitals

While non-native migration to California was minimal under Spanish (1769–1821) and Mexican rule (1821–1848), the gold rush functioned as a catalyst to realize the westward ambitions of a rapidly expanding U.S. population. As the popular story goes, in January 1848, an American carpenter from New Jersey, John Marshall, discovered a piece of gold on the American River just days before the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo—officially ending the Mexican-American War and transferring over half of Mexico’s land holdings that would eventually become part of Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. However, Congressmen in Washington long knew of the mineral wealth of California, as did many of San Francisco’s first merchants, some of whom had previously mined for gold and silver in Mexico, Chile, and Peru.1 Gold fever was thus initiated by President James Knox Polk by publicly confirming the mineral wealth of California in his State of the Union address, stating he was “deeply interested in the speedy development of the country’s wealth and resources.”2

When what is now known as California formally came into the possession of the United States in 1848, the territory was characteristic of a North American borderland, represented by the intermixing and co-habitation of descendants of one of the largest and most diverse pre-contact indigenous populations in the western hemisphere, Spanish missionaries, Mexican colonial authorities, Californios, and Russian fur traders, amongst others.3 In its rapid population gains and transformation from a territory to a state, the racist ideologies that settlers brought with them from other parts of the country structured the state’s first organizing efforts.4 While, after much debate, California was not admitted to the nation as a slave state, its first laws reinforced a racial hierarchy that shaped gold-rush communities. A combination of miner’s ethics and Manifest Destiny ethos led to the state’s first legislation being dependent on a suite of labor, vagrancy, voting, citizenship, and tax laws that prevented Indigenous peoples, Blacks, Mexicans (or Californios), and Asians from equality or justice, and regulated their participation in the development of the state.5 In the impromptu urban quarters of San Francisco, for instance, an Overseas Chinese community grew alongside other immigrant enclaves, but were instantly subject to processes of racialization and ultimately equated with vice and disease.6

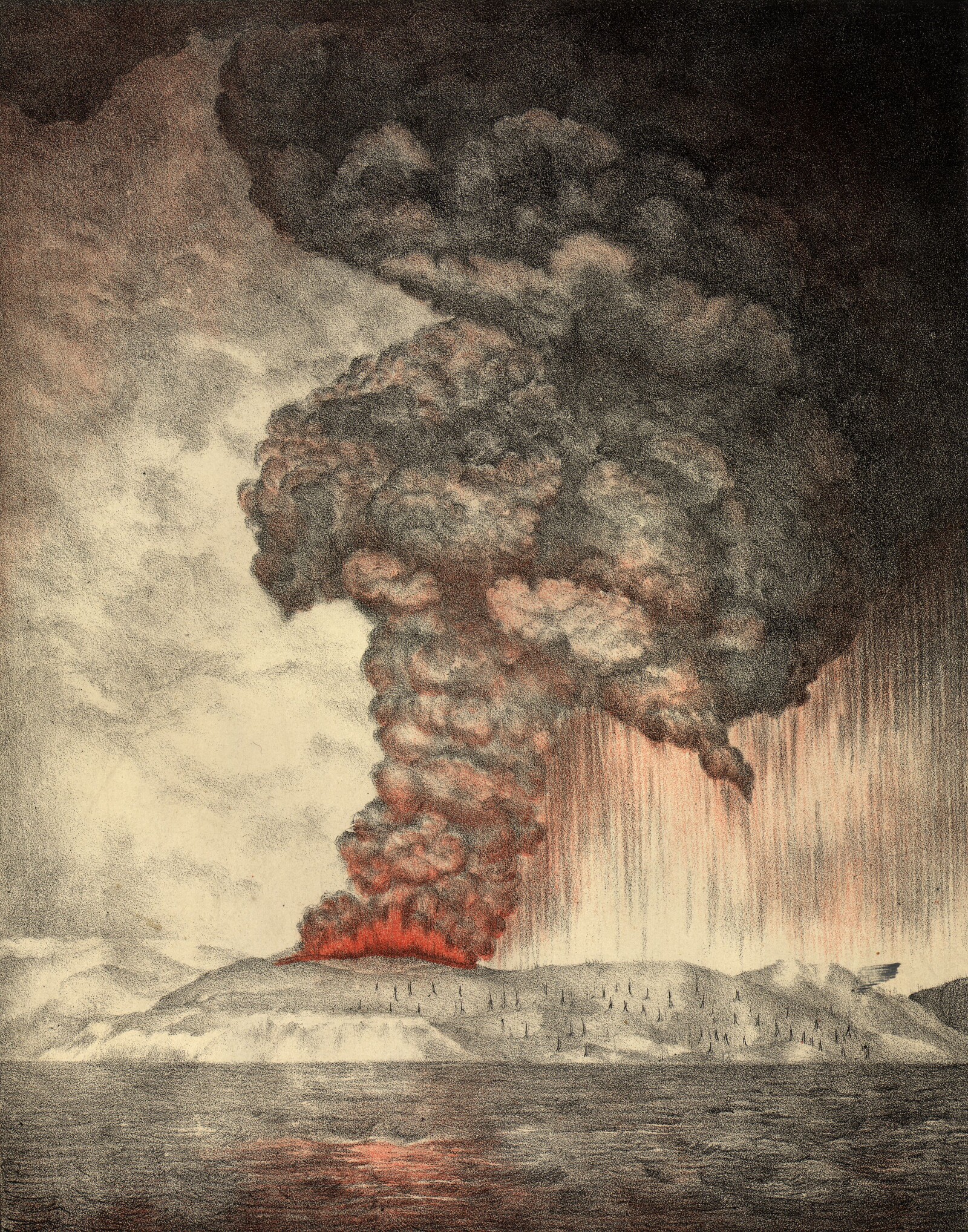

Just over a year into the gold rush, in 1849, a nationwide cholera epidemic raged in New York and New Orleans, and the mass-migration westward gave Vibrio comma the opportunity to penetrate the Pacific coast. San Francisco was the epicenter of the first outbreak.7 With nearly 40,000 emigrants passing through San Francisco on their way to the goldfields in 1849 alone, dire conditions prevailed. As one observer described the city, “for the filth and dirt in the many vacant lots, of the stagnant water, the putrefying carcasses, one can scarcely form and idea.”8 In short, the dramatic population increase, lack of proper housing and shelter, limited fresh water supplies, and inadequate or non-existent sewer systems fostered a deluge of disease. Perhaps nowhere in mid-nineteenth-century America was the process of urbanization and adjustment to disease more severe than in the instant cities of California.9

While the 1850 federal census indicates that California contained more physicians per-capita than any other state at the time, hospitals and a formalized system of healthcare was non-existent, and disease and death were common.10 In addition to Cholera, San Francisco at the time was also struck with outbreaks of malaria, yellow fever, typhoid, ophthalmia, smallpox, and scurvy. As the city’s population expanded, the health care needs of the city increased exponentially, which led to the construction of the city’s first formalized network of hospitals. These institutions not only managed the sick and dying, but also solidified group membership, citizenship, and ultimately promoted assimilation by developing co-ethnic, co-national, and co-religious healthcare, normalizing a predominately Western European population.

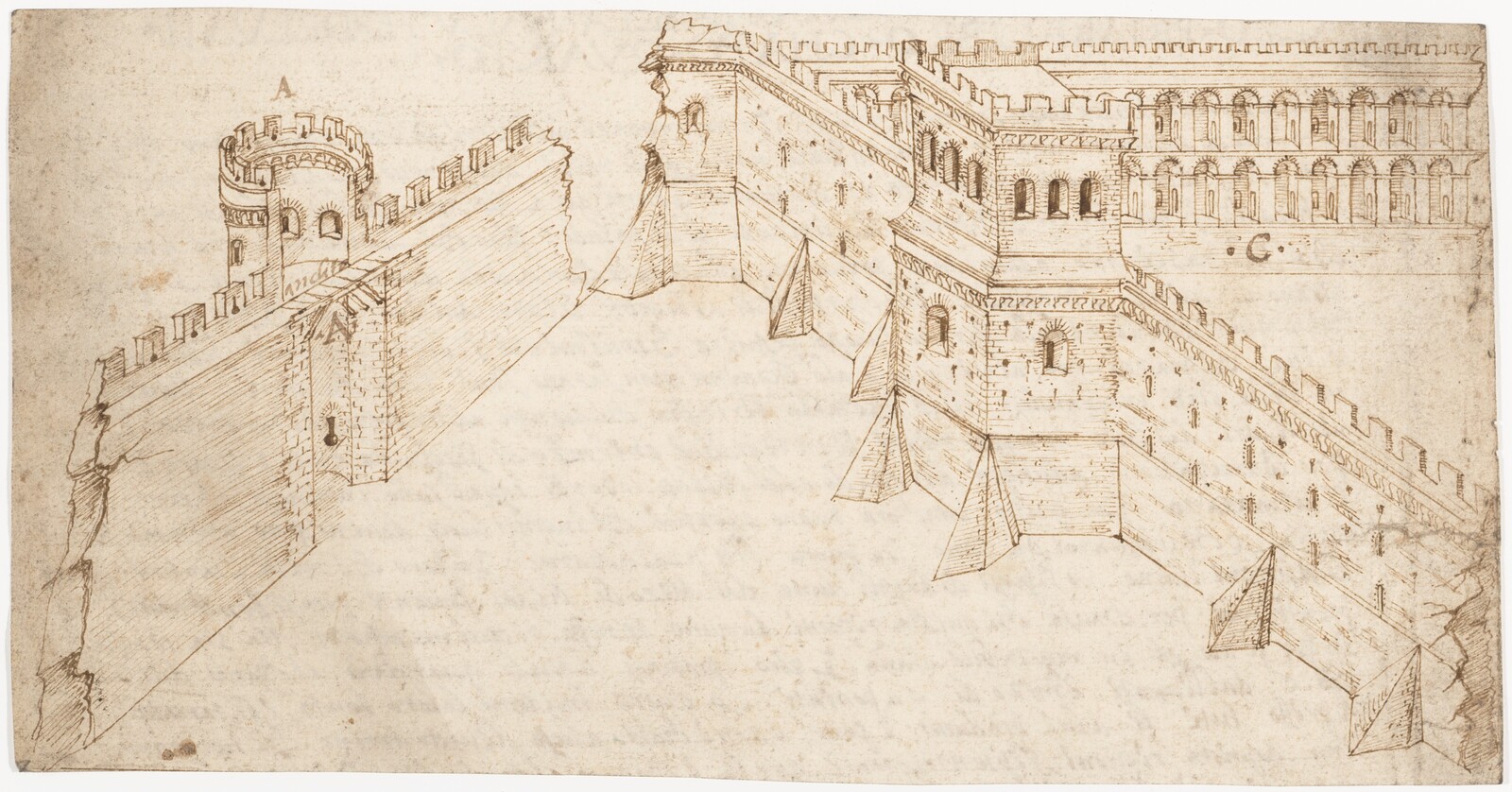

Between 1850 and 1890, seven formally planned modern hospitals were constructed within the city. Some of the original facilities were damaged by earthquakes or fire, and moreover, as the city’s population grew, most couldn’t accommodate the increase in patient volume. Since advances in modern medicine were unfolding concurrently with hospital design, many of the first hospitals were not adaptable to modernization. More importantly, novel versions of these hospitals solidified the influence and success each of these organizations accumulated during the state’s tumultuous early history. Depending on the date of publication, many of these hospitals (original and subsequent builds) were memorialized alongside important city monuments on early maps. These included the first French Hospital (1851), the first U.S. Marine Hospital (1853), the first Catholic St. Mary’s Hospital (1857), the first German Hospital (1858), the first Episcopal St. Luke Hospital (1871), the City and County Hospital (1872), and the Jewish Mt. Zion Hospital (1887).

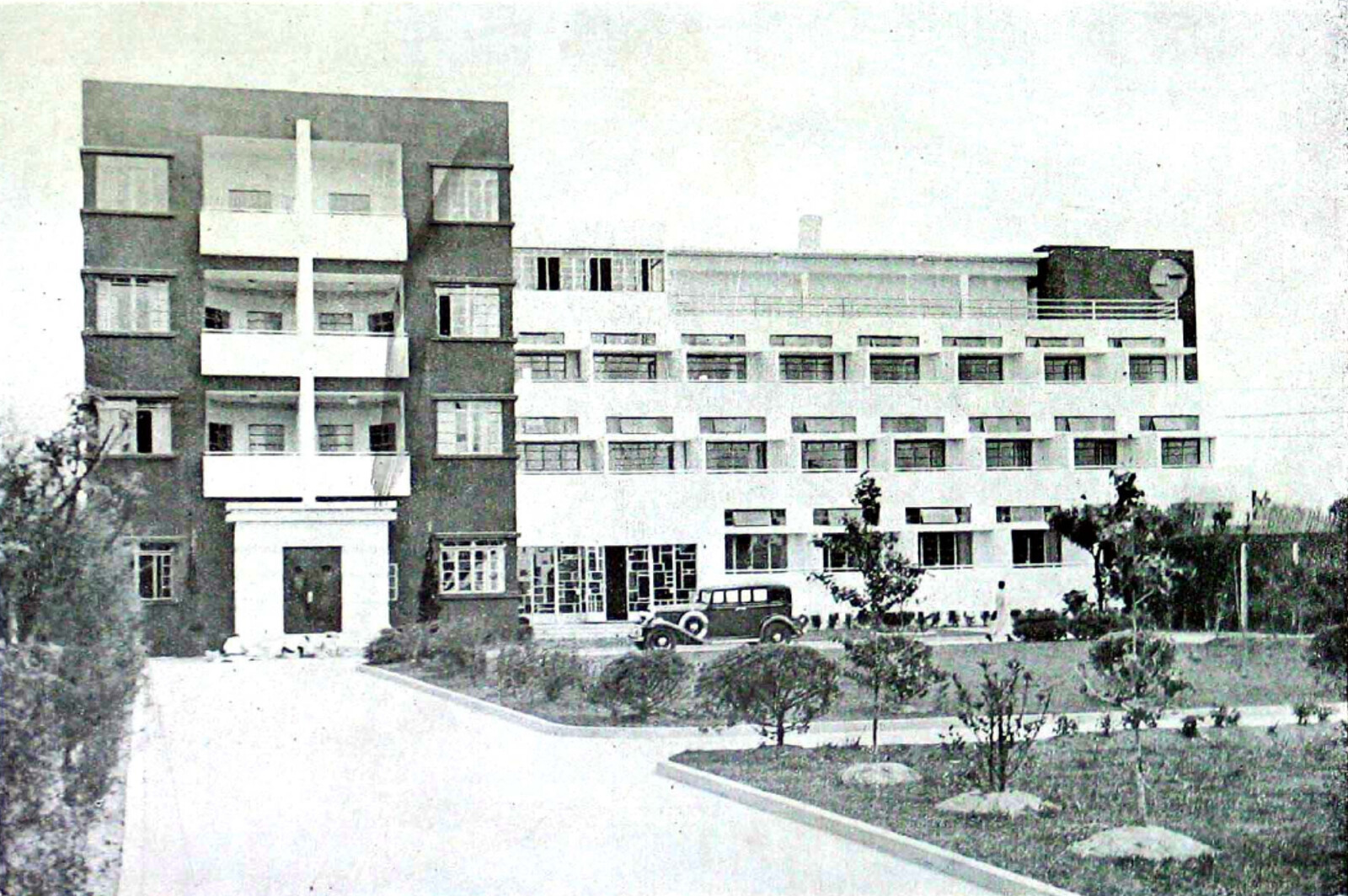

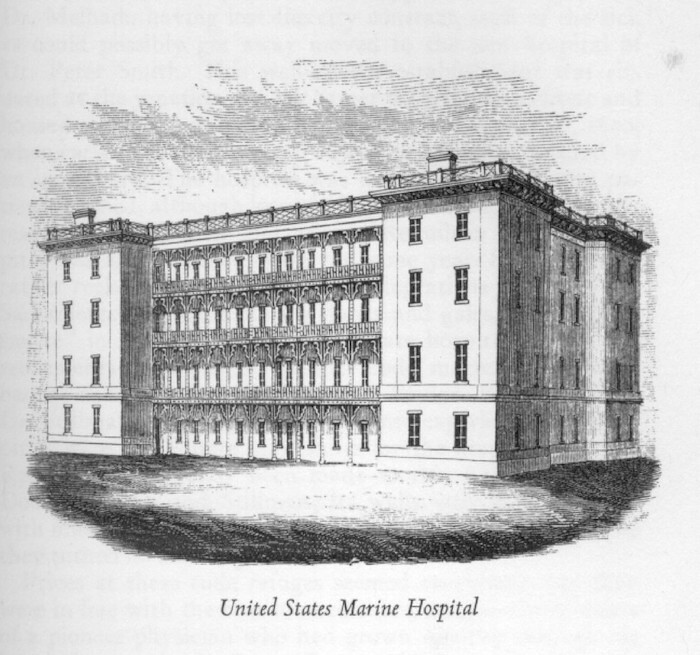

Through an act of Congress, the U.S. Marine hospital was the first publicly funded building in the state of California. Designed by Robert Mills, who is often described as America’s first native-born architect.11 Built in 1853 on Rincon Point, along the eastern (bay) side of the city, it was described at the time as “large, strongly built, and luxurious.”12 Following two earthquakes, it was abandoned, and by 1875, it was rebuilt in the new French-derived “pavilion system” as a healthcare compound at a new rural location within the city’s adjoining U.S. military installation, the Presidio. The new timber-framed complex with brick foundations overlooked a natural lake and included three long rectangular ward buildings that radiated from a central reception building. Several additional ancillary support structures were placed on either side of the wards.13 Within fifty years, the hospital was functionally obsolete and a severe fire hazard. In 1928, federal legislation appropriated funds to the newly named Public Health Service for a new (third) Marine Hospital—considered to be one of the agency’s most ambitious building projects at the time. The main hospital was now a six-storied reinforced concrete structure that accommodated growing advances in medicine.14 It was also representative of a “crucial period” of hospital design, when American hospitals shifted from pavilions to high-rises.15

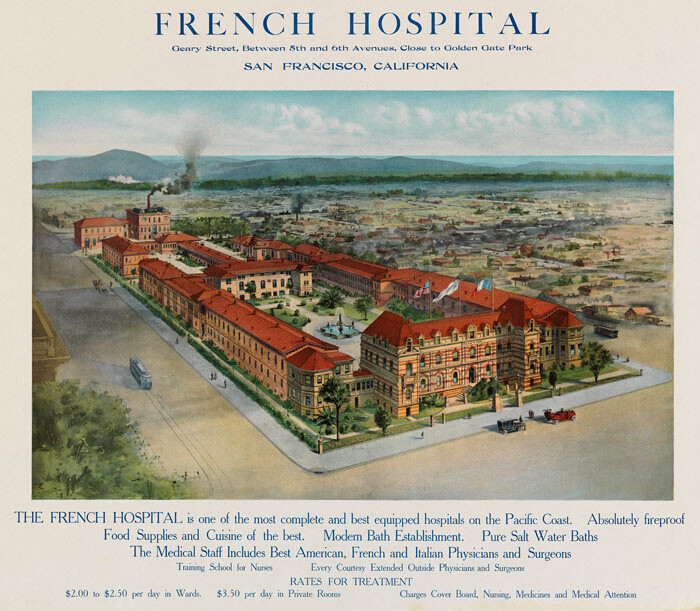

Similarly, the French Hospital was reimagined and rebuilt for the fourth time in 1893. When it was completed, the complex of fourteen buildings were said to have utilized five miles of electric wire, one of the most extensive electrical projects completed in the city.16 A little over a decade later, the third German Hospital was erected and touted as “the most complete and perfect, as well as the largest hospital in the western half of this continent.” Its modern-renaissance styled complex also represented the “new departure in modern hospital construction” that favored two, compact high-rise buildings to facilitate “the administration and economy” of the hospital.17 Collectively, the city’s first modern hospitals and the ideals they represented transformed a city of crude architecture and disease into a symbol of modern medicine and design. Indeed, by the close of the twentieth century, San Francisco contained the largest number of hospital beds in relation to its population than any other city in the nation.18

Close-up of City and County Hospital, The Commercial, Pictorial, and Tourist Map of San Francisco, 1904.

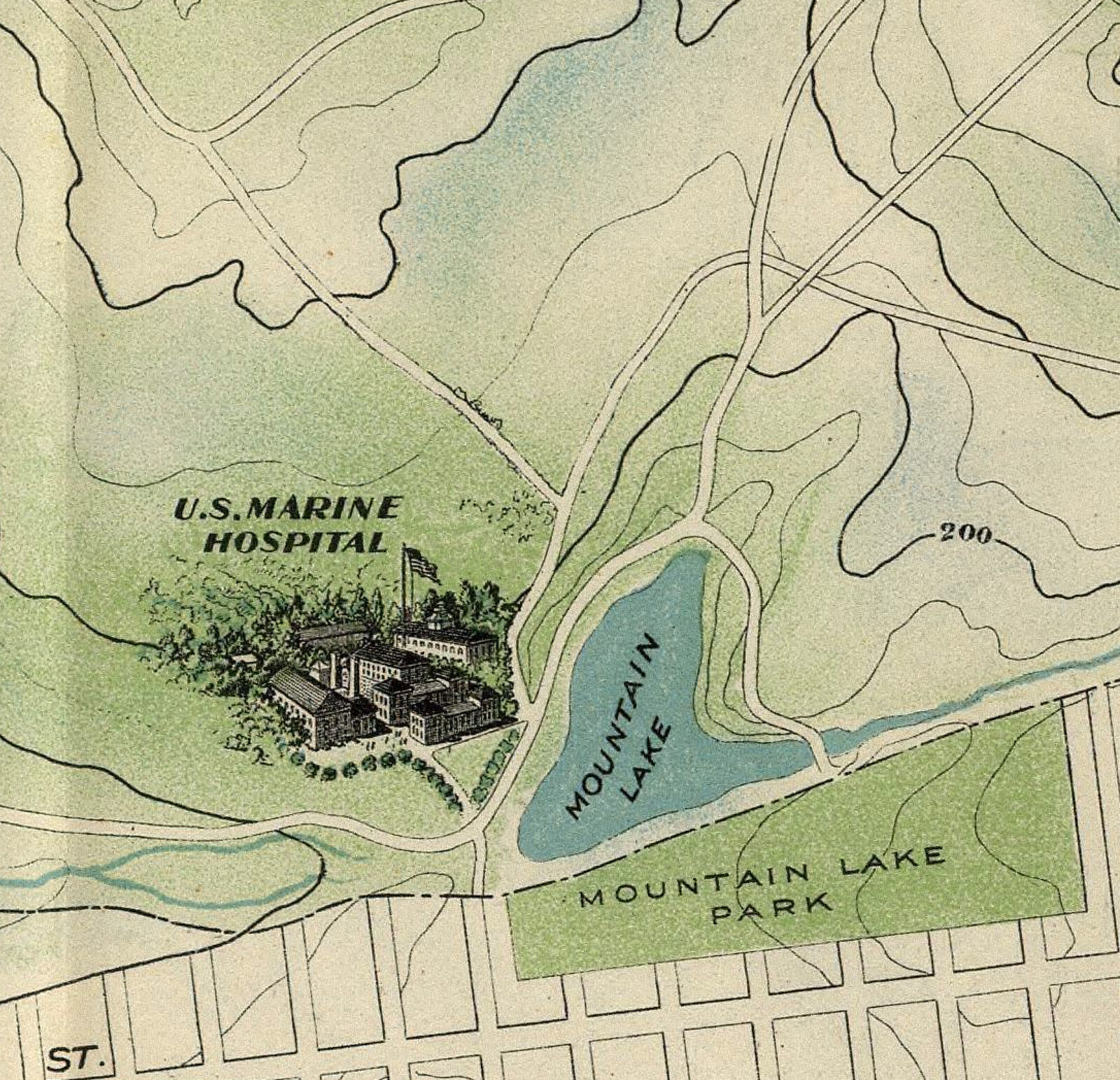

Close-up of U.S. Marine Hospital, The Commercial, Pictorial, and Tourist Map of San Francisco, 1904.

United States Marine Hospital, ca. 1853, author unknown. The first publicly funded building in the state of California, designed by architect Robert Mills. The hospital was severely damaged following two earthquakes and was abandoned by the Marine Hospital Service in the 1870s. Image accessed from the University of California San Francisco Archives and Special Collections.

Close-up of French Hospital, The Commercial, Pictorial, and Tourist Map of San Francisco, 1904.

Postcard, French Hospital, San Francisco, California. This is the fourth and final iteration of the French Hospital. It was designed by Franco-American architect M.G. Morin-Goustiaux, in collaboration with M. Mooser and the cornerstone was laid in 1894. When completed it was said to have been regarded as the most modern hospital on the Pacific Coast. It was considered a model for hospital planning with it courts and gardens, its equipment were the finest, and it hosted one of the first nursing schools in San Francisco. Image accessed from California State Library, Digital Collections.

Close-up of German Hospital, The Commercial, Pictorial, and Tourist Map of San Francisco, 1904.

Postcard, Franklin Hospital, San Francisco California, 1921. Renamed the Franklin Hospital because of Germany’s involvement in World War I, the new hospital was designed by architect Hermann Barth (1865–1923) who was born in Germany and immigrated to San Francisco in 1881. Barth was a practitioner of numerous types of architecture and designed several hospitals for the city and was a member of the San Francisco Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Drawings from his practice are held at U.C. Berkeley. Image accessed from East Carolina University’s Digital Collections.

Close-up of City and County Hospital, The Commercial, Pictorial, and Tourist Map of San Francisco, 1904.

Normalizing Stigma Through Public Health

Since pestilence was inherent to most nineteenth-century-urban spaces, cities all over the world established public health organizations with broad authority to survey, monitor, and in effect, “police” the health offences of its inhabitants.19 In San Francisco, this manifested through the authority of state and local “health experts” that organized health boards to prioritize issues and enact remediation. This system of oversight incorporated architects and architecture as essential participants in constructing modern and acceptable notions of health and sanitation.

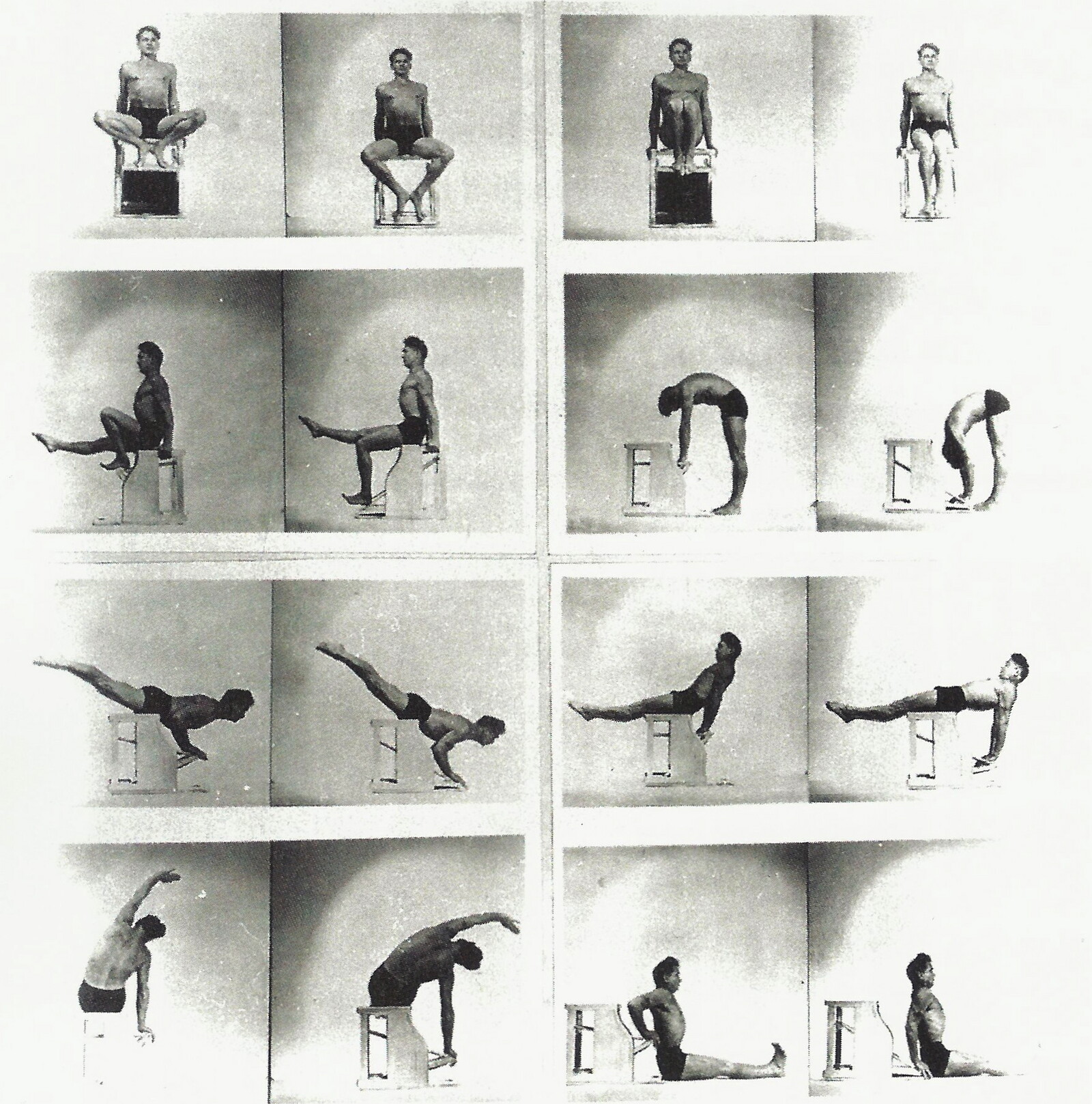

Indeed, following the first two decades of statehood, the first biennial report of California’s State Board of Health (published in 1871) defined a range of state-wide health problems common to the nineteenth century. Miasma theory—the notion that foul noxious air transmitted pestilence—was still accepted as the main cause of disease at the time. Sanitary architecture and municipal practices that incorporated proper design, building materials, and legislation tested and vetted by English, French, and German “authorities” were discussed in relation to hospitals and other public buildings, management of the dead and burial grounds, sewerage, land reclamation, and water supply.20

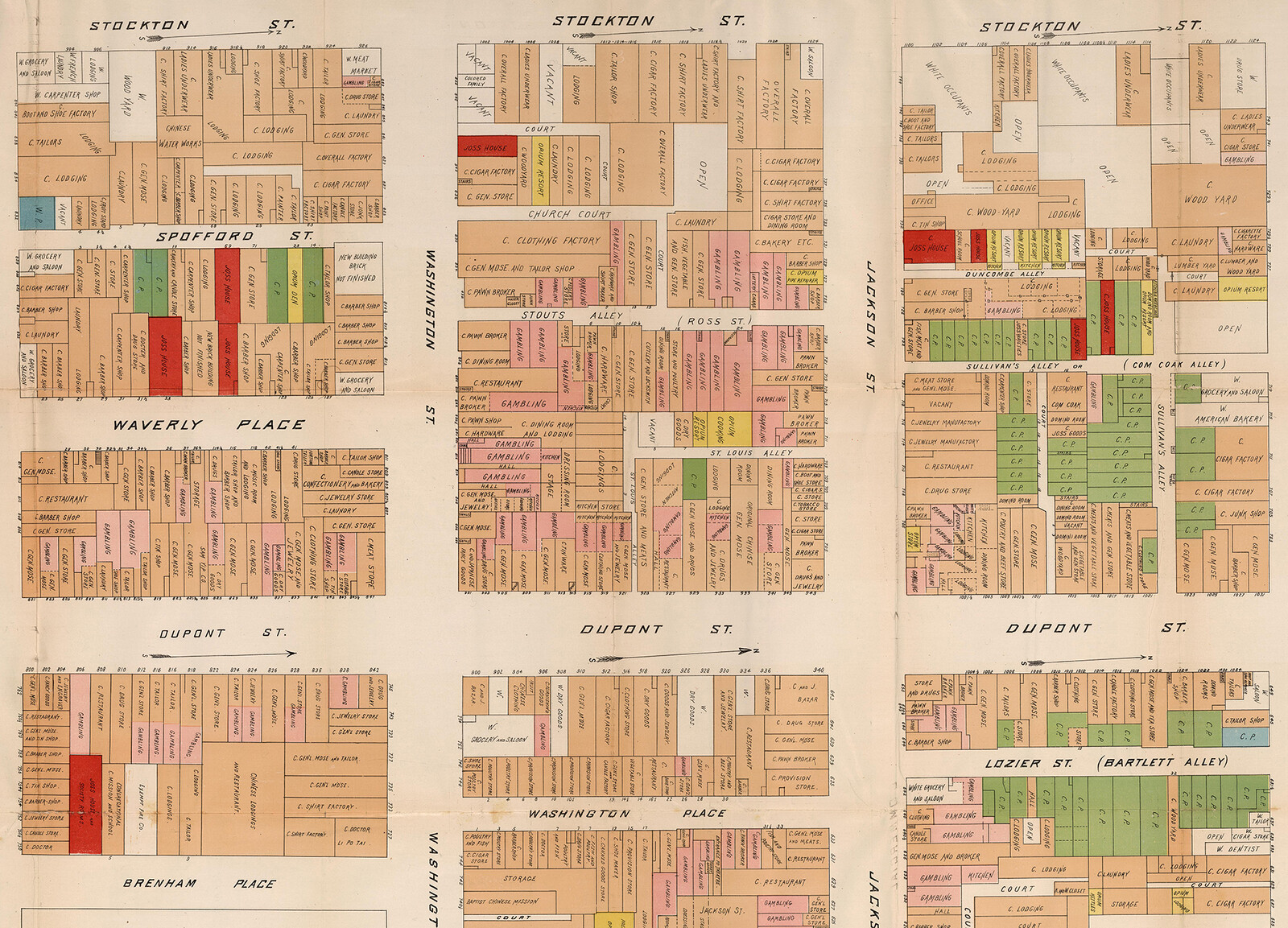

In San Francisco, health concerns specific to Chinese immigrants—such as personal hygiene, living conditions, and their complicity in prostitution—were considered “special questions” of the board.21 From the board’s perspective, the Chinese represented not only a public health concern, but a nefarious presence that needed swift remediation. The report stated that the “Mongolian portion” of the population were not only “totally regardless of all sanitary laws … but none who have ever witnessed the midnight orgies of this hebetated people in San Francisco, can imagine the depths of depravity into which they are sunk.”22 An account of a midnight survey of the “Chinese quarter” by doctors, a medical heath officer, and a city police officer details a visit to “the lowest dens of degraded bestiality.” The account describes “foul labyrinthine passages” that connect dark rooms housing “dusky human beings, lying on tiers of broad shelves, like the berths of a ship.” Rooms were described as “pens” absent of proper ventilation.

In the slowing California economy of the 1860–1870s, white workers formed racist associations throughout the state such as the “Anti-Coolie Association,” which largely blamed male Chinese laborers—who had originally come to California primarily in response to labor demands—for their inability to find work.23 They also pressured public health officials to enact sanitary laws to encourage Chinese emigrants to return to China.24 The State Board of Health was therefore not just guilty of reinforcing racist attitudes, but actually an instrument to enact a racist agenda.

If modern hospitals constructed by French, German, Christian, Jewish, and government organizations represented normality, citizenship, and the cure, San Francisco’s Chinatown and its working-class were abnormal, alien, the disease. As one scholar puts it, “Chinatown was not simply associated with smallpox, plague, and syphilis: it was made metonymous with these diseases. That is, its labyrinthine alleyways, mysterious josshouses, and grimy brothels were construed not just as spawning these diseases or containing them, but as actually becoming a part of them.”25 While San Francisco’s modern hospitals were monumentalized in city maps, Chinatown became a monument to both disease and vice, reinforcing both an architectural and “spatial pathologization.”26

The backlash the Chinese experienced as a result of their alienation in San Francisco and beyond supported the passage of federal legislation such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Geary Act in 1892, as well as a host of other localized legislation to limit Chinese immigration to the United States as a whole, but particularly California.27

Given the special attention and pathological blame the Chinese population experienced for the degeneration of city health, they were almost completely forbidden to access to most of the city’s healthcare facilities.28 As a result, subterranean “chambers of tranquility” to aid recovery or death and herbal shops scattered throughout Chinatown, constituting a rival healthcare support system under constant scrutiny and effective constraint.29

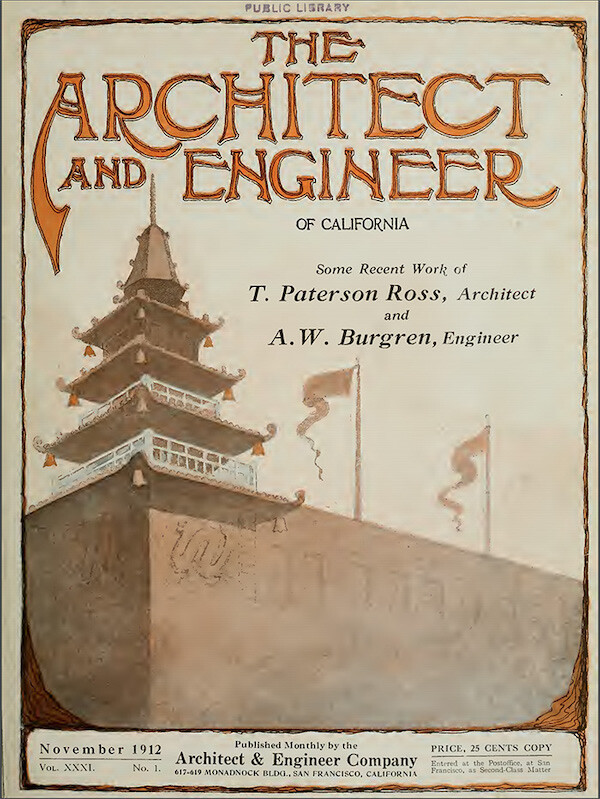

Front cover of The Architect and Engineer of California 31, no. 1, November 1912. Cover shows the Sing Fat Building in Chinatown, designed by architect T. Paterson Ross and engineer A. W. Burgren.

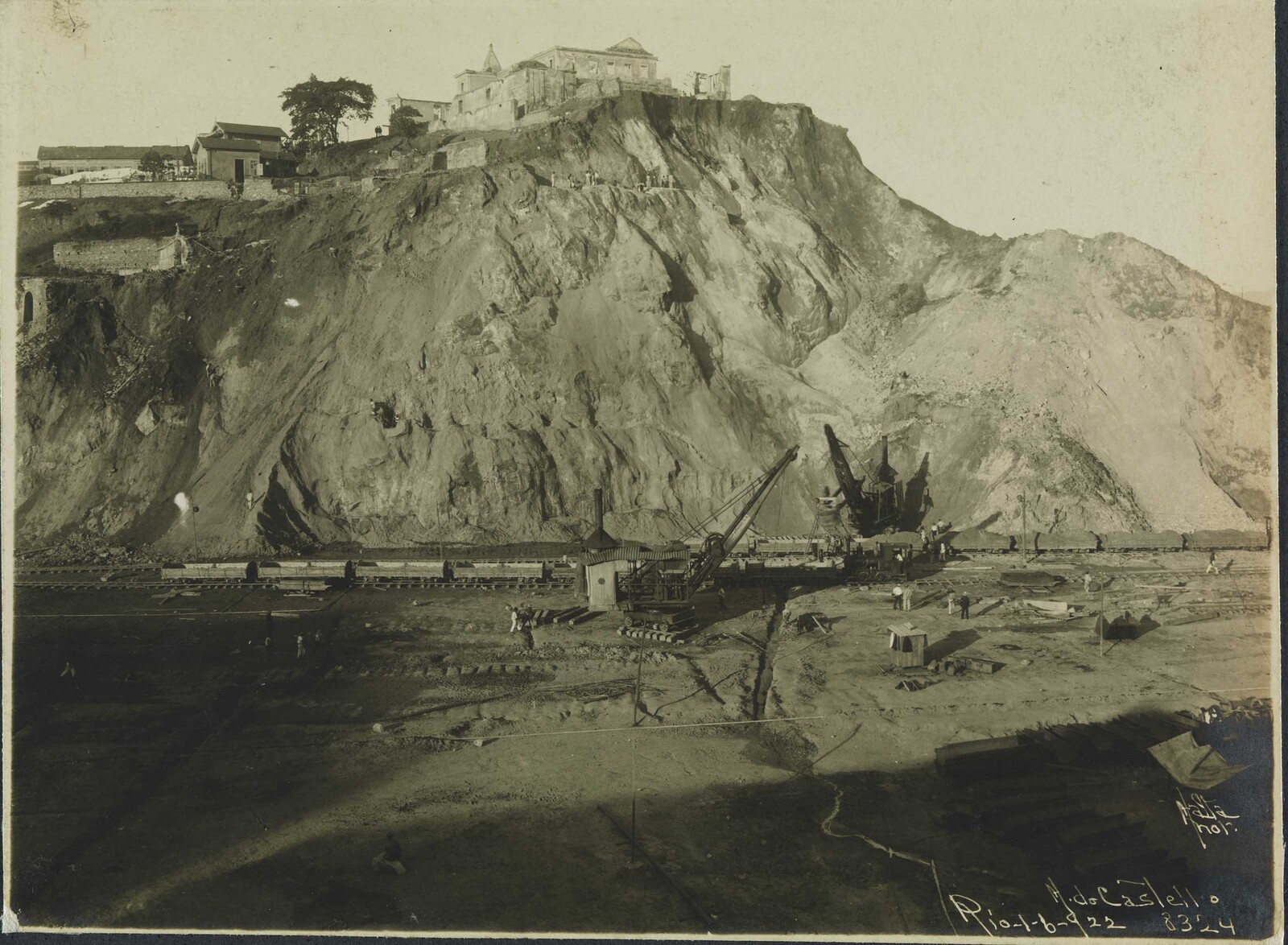

The 1906 earthquake was a seminal moment in the city’s architectural history, as the violent shaking and subsequent fires destroyed some 28,000 buildings—including all of Chinatown. Its complete destruction was touted as a purification for the city, and its rebuilding was predicated on a “sanitary plan” that catered to tourism and police surveillance. The new buildings were also carefully designed by white architects from firms such as Ross & Burgren to promote a new “Oriental City” donned in a “imitation oriental” style architecture. Most recognized architects in San Francisco were white males trained in the Beaux Arts tradition and neither studied nor cared for Asian styles of architecture. Therefore, the new oriental city was an architectural hybrid that transformed ancient Chinese forms into a new Sino-architecture using western construction methods, local materials, and in compliance with local building codes.30 And while it was believed that the new Oriental City would encourage its Chinese residents to adopt more sanitary practices, San Francisco’s Chinese and Chinatown continued to be associated with disease.31

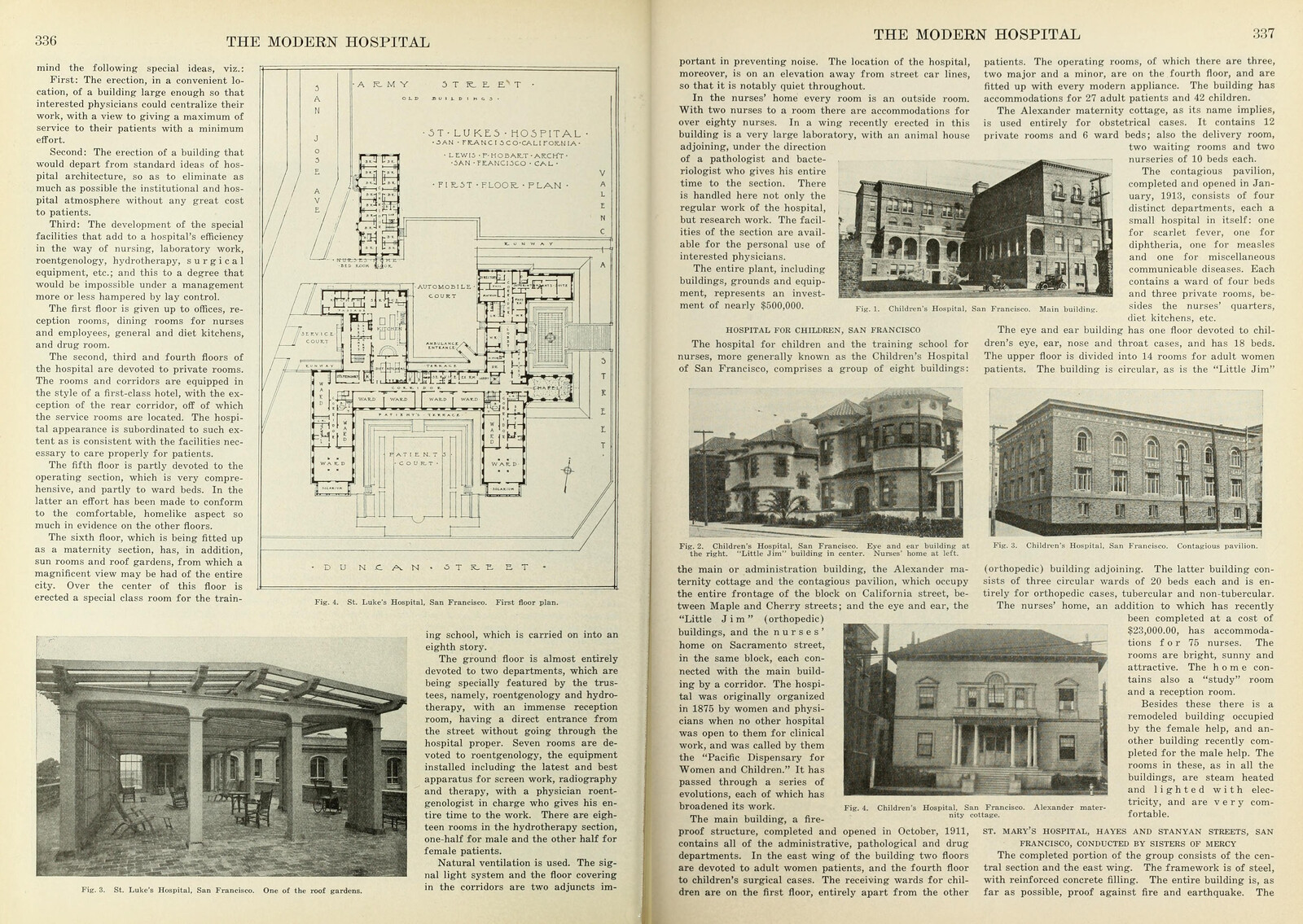

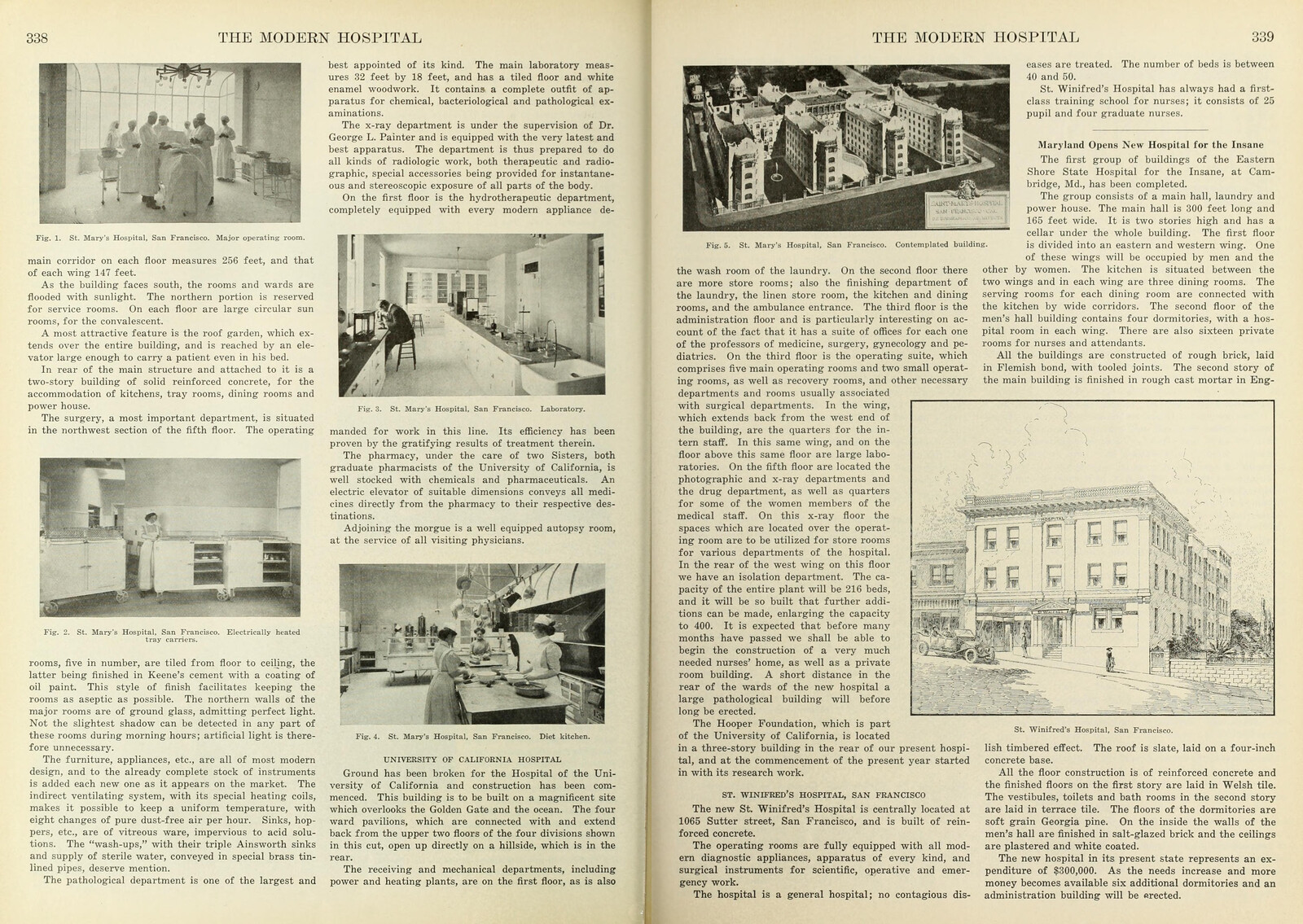

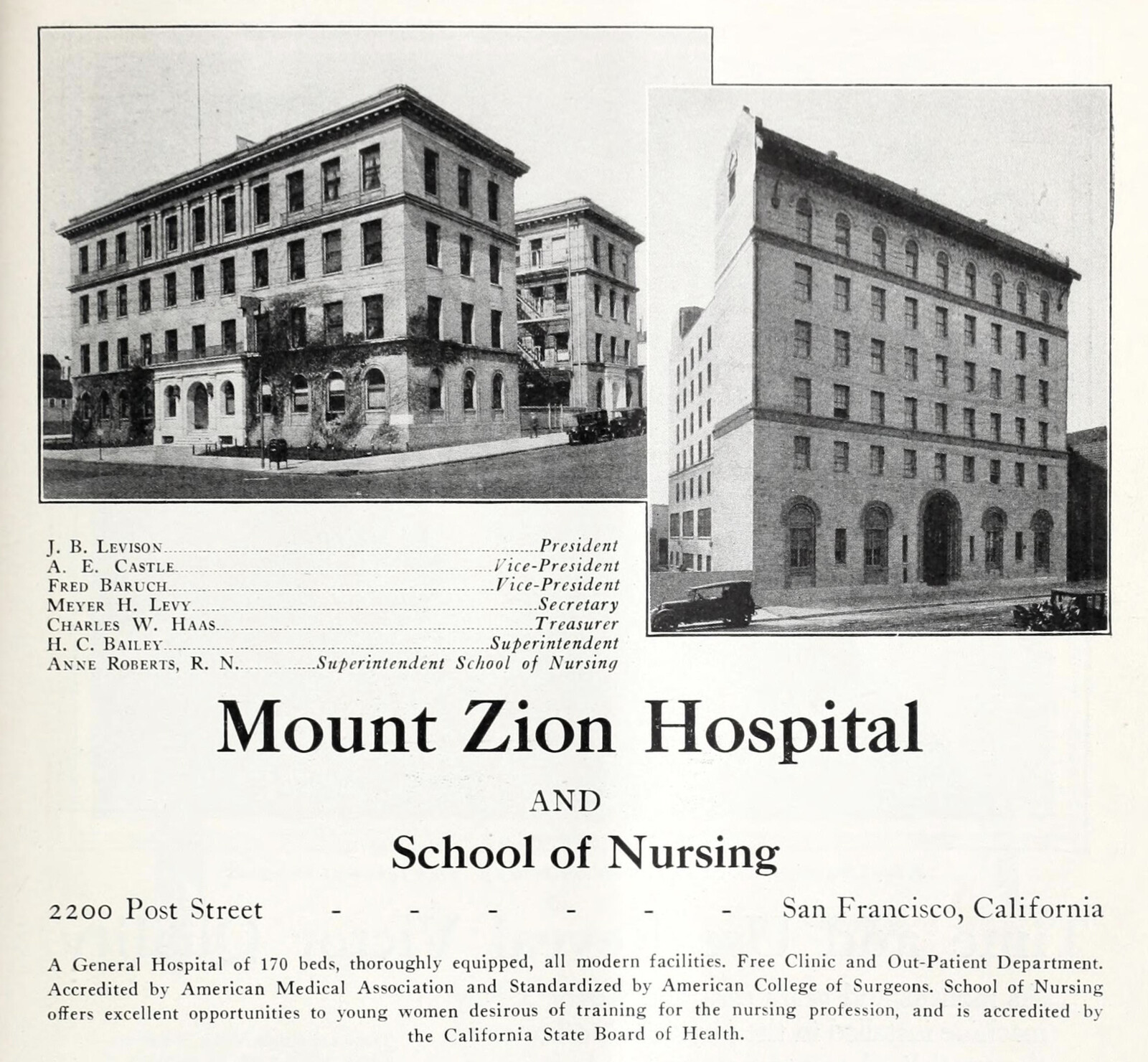

Meanwhile, many of San Francisco’s nineteenth-century hospitals either continued to operate, were remodeled or rebuilt following the earthquake, continuing to not only communicate an image of modern health and normality, but also effectuate practices of citizenship and assimilation into the white Anglo-American fabric of San Francisco and the United States. This can be seen by the usage of the hospitals images in early twentieth-century postcards and in advertisements that marshal the hospital’s architecture to communicate control, credibility, and civic pride.32 Trade journals such as Modern Hospital (established in 1913) also served to publicize the interiors and floorplans of some of San Francisco’s hospitals, commodifying not just their exterior architecture, but also reinforcing and normalizing a new relationship between private spaces, public consumption, and mass media.33

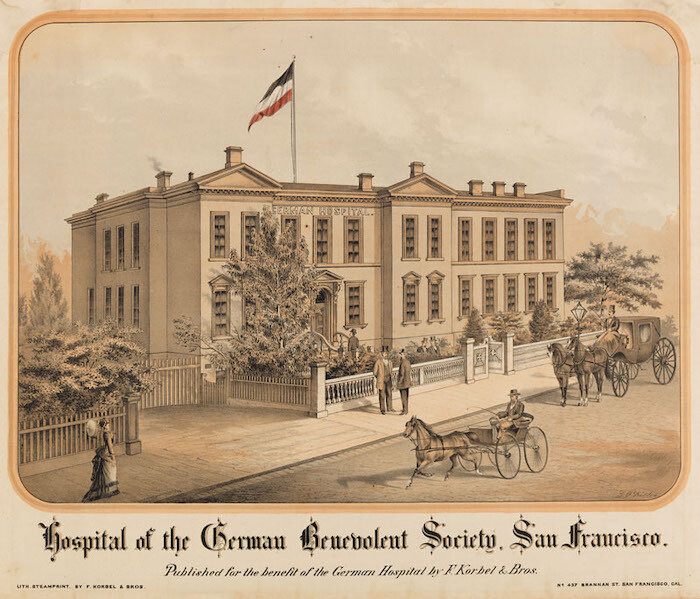

Postcard, Hospital of the German Benevolent Society, San Francisco. Published for the benefit of the German Hospital by F. Korbel & Bros. This postcard depicts the first German Hospital, constructed in 1858. The society’s founder, Joseph N. Rausch, M.D., also created one of the first known pre-paid health plans whereby German-speaking immigrants could pay a dollar a month to secure a private hospital bed at a rate of one dollar per day. This first iteration of their hospital was destroyed by a fire in 1876. Image accessed from California State Library, California History Section Picture Catalog.

Floor plan and photograph of St. Luke’s Hospital featured in The Modern Hospital: A Monthly Journal Devoted to the Building, Equipment, and Administration of Hospitals, Sanatoriums, and Allied Institutions, and to their Medical, Surgical and Nursing Services 4, no. 5, 1915.

Interior photographs and contemplated building model of St. Mary’s Hospital featured in The Modern Hospital: A Monthly Journal Devoted to the Building, Equipment, and Administration of Hospitals, Sanatoriums, and Allied Institutions, and to their Medical, Surgical and Nursing Services 4, no. 5, 1915.

Advertisement for Mount Zion Hospital and School of Nursing from California and Western Medicine Advertiser 23, no. 6 (June 1925).

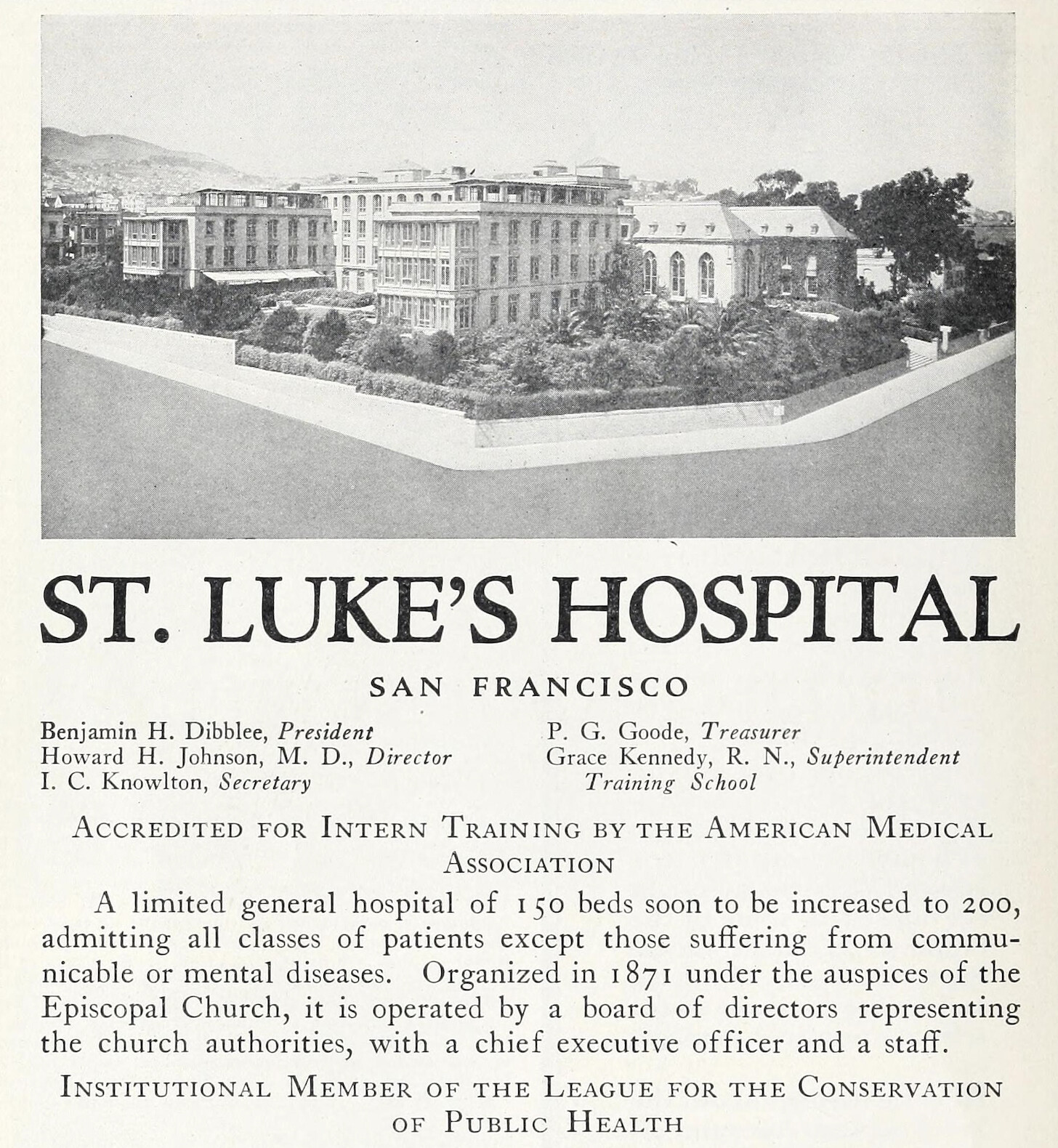

Advertisement for St. Luke’s Hospital from California and Western Medicine Advertiser 23, no. 1 (January 1925).

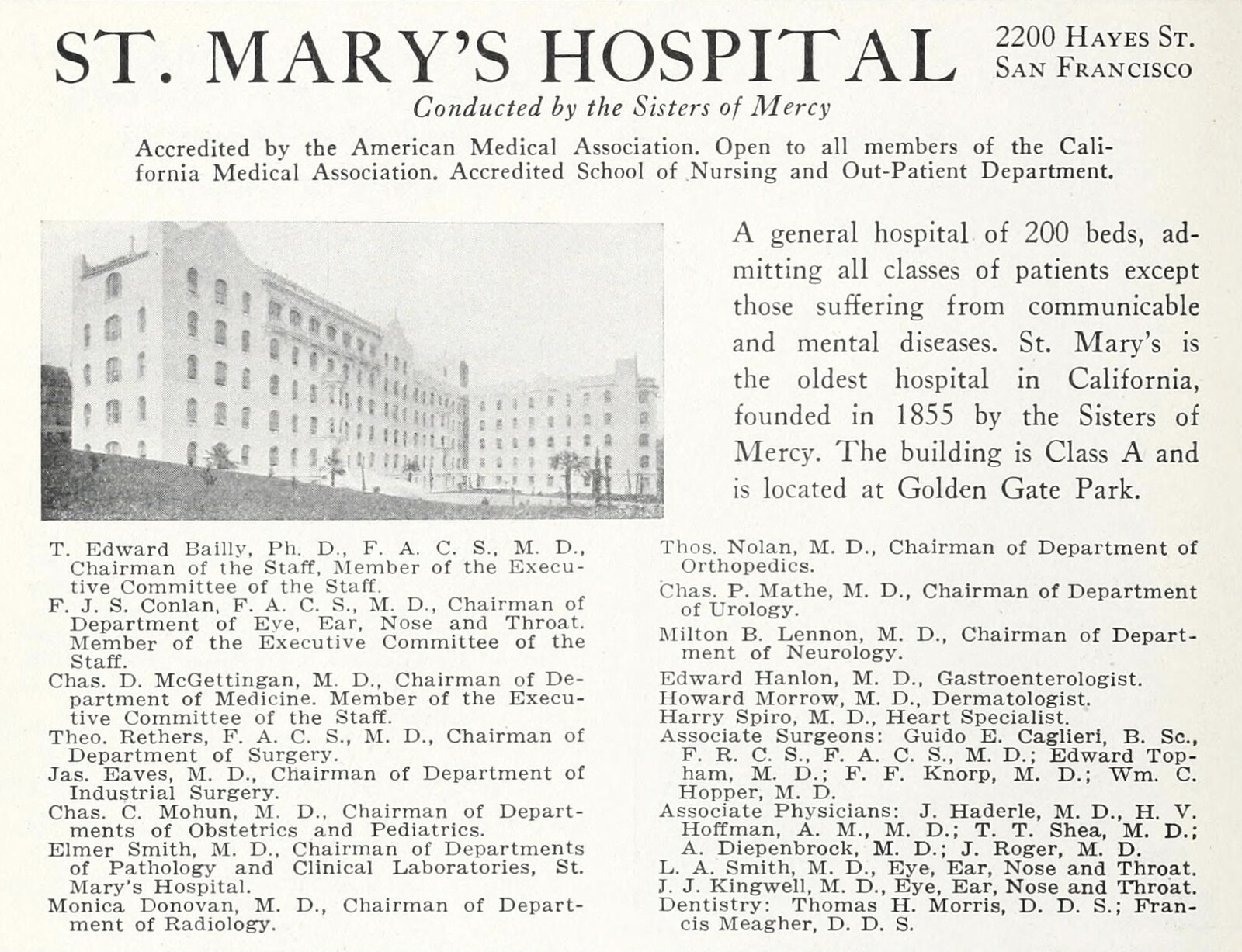

Advertisement for St. Mary’s Hospital from California and Western Medicine Advertiser 23, no. 1 (January 1925).

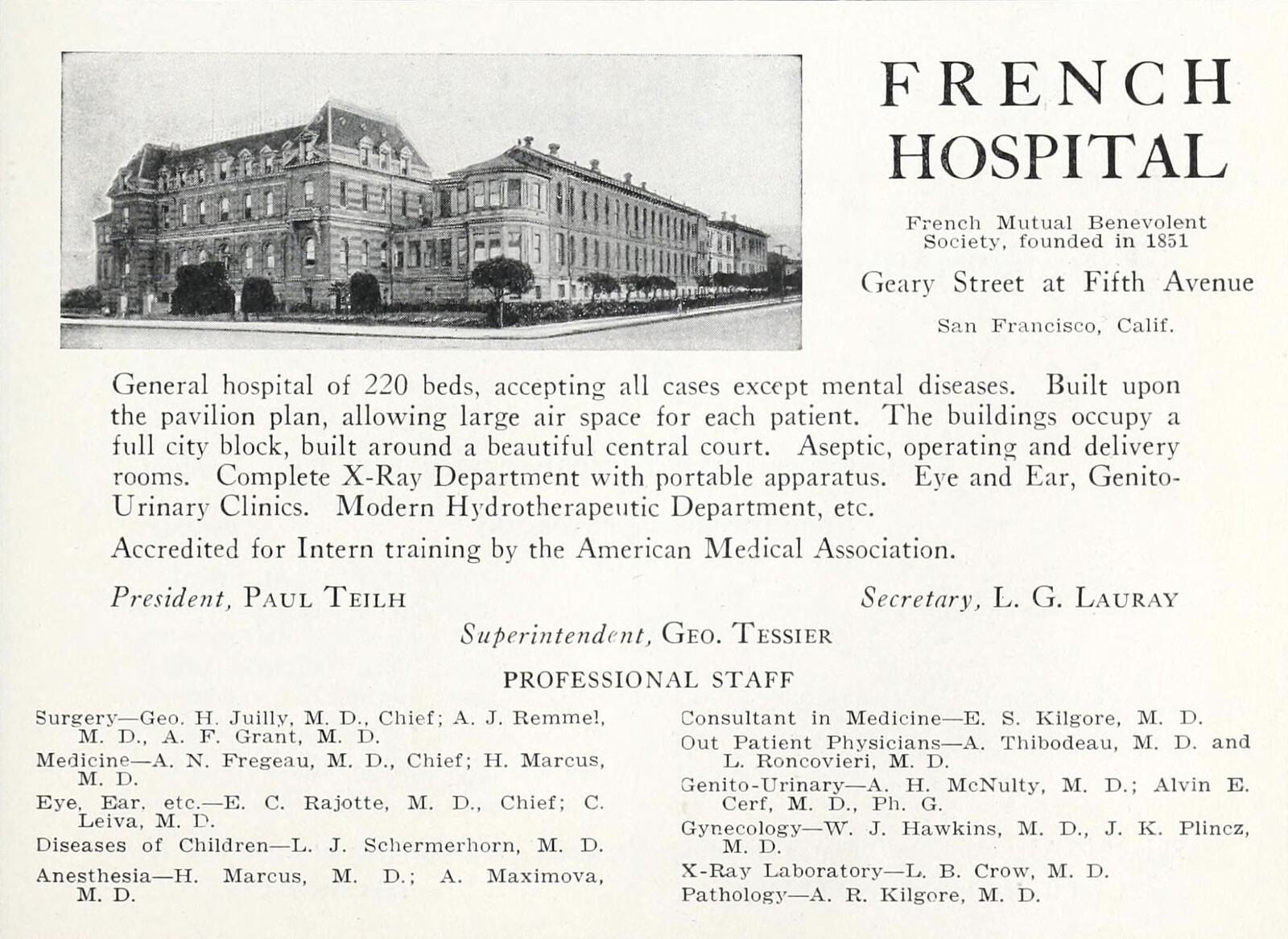

Advertisement for the French Hospital from California and Western Medicine Advertiser 23, no. 1 (January 1925).

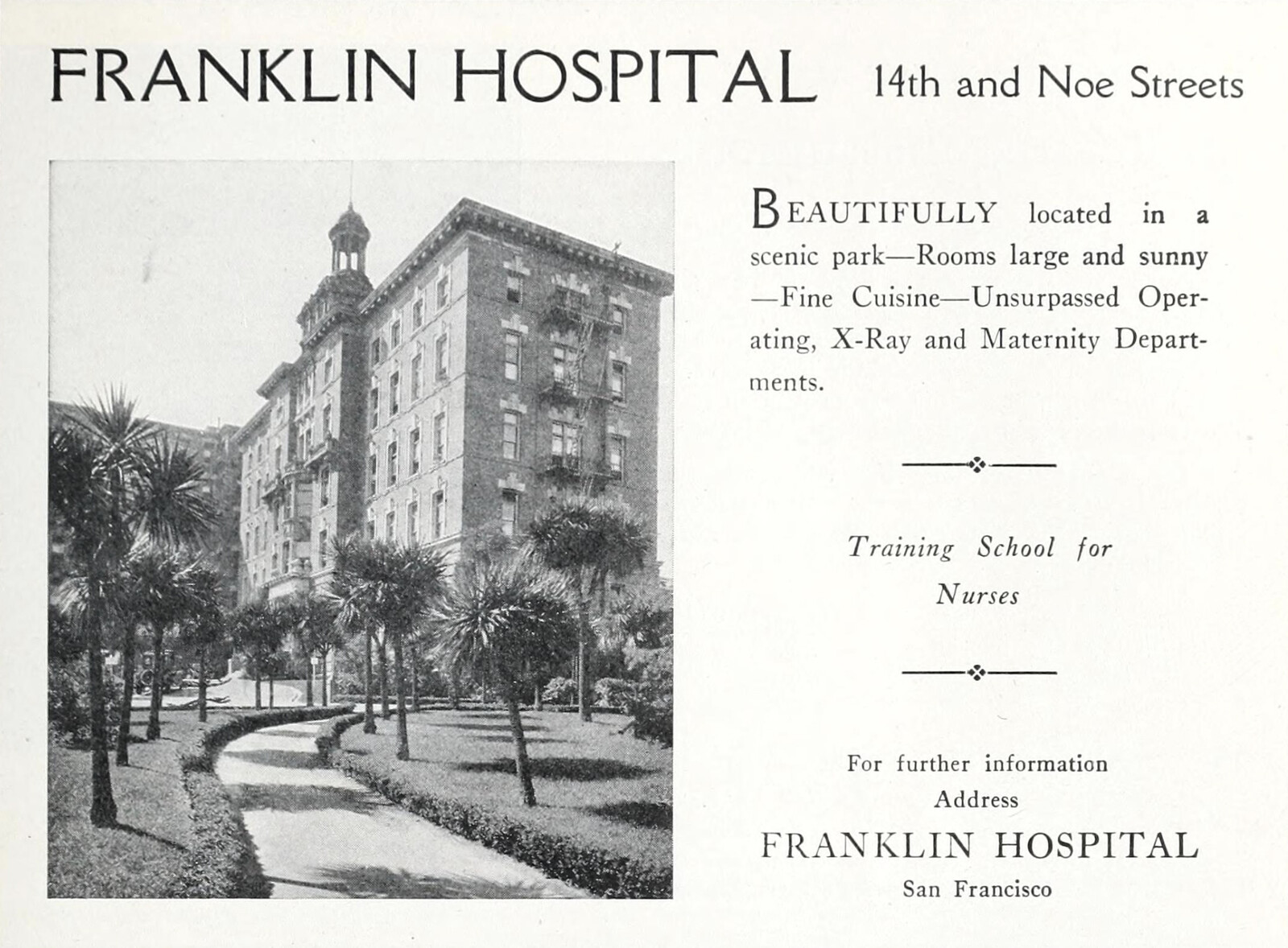

Advertisement for the Franklin Hospital from California and Western Medicine Advertiser 23, no. 1 (January 1925).

Postcard, Hospital of the German Benevolent Society, San Francisco. Published for the benefit of the German Hospital by F. Korbel & Bros. This postcard depicts the first German Hospital, constructed in 1858. The society’s founder, Joseph N. Rausch, M.D., also created one of the first known pre-paid health plans whereby German-speaking immigrants could pay a dollar a month to secure a private hospital bed at a rate of one dollar per day. This first iteration of their hospital was destroyed by a fire in 1876. Image accessed from California State Library, California History Section Picture Catalog.

It took almost twenty years after the earthquake and the architectural reform of Chinatown for a commitment to be made by San Francisco’s civic leaders to actually improve, and not simply criminalize and impose or regulate the living and social conditions of the Chinese community. The emergence of a new population of educated second-generation Chinese Americans “helped bridge the chasm between the Chinese American Community and dominant white society” in this task.34 Post-earthquake, charitable Chinese, American, and Christian organizations pledged money and led the way in finding ways to integrate traditional Chinese medical knowledge and western medicine. Given the decades of pathologizing Chinese bodies, practices, space, and architecture, such constraints led to compromise. The community therefore looked to the British colonial city of Hong Kong for inspiration of how to successfully, or acceptably commingle western medical science with traditional Chinese practices.35

Finally, in 1925 the modern Chinese Hospital (東華醫院) was constructed in Chinatown. To this day, it is the only Chinese hospital in the United States, and was described at the time of its opening as “marking the most modern advance of Orientals in this country.”36 The four-story reinforced-concrete building originally accommodated fifty-five beds, a surgical department with two operating rooms, a maternity department with a delivery room, a pharmacy, a lab, and an outpatient department. The hospital reflected the general trend of Chinatown’s rebuilding to embrace an overtly stylized version of Sino-architecture.37 Its form was said to have been copied from the hospital of the Rockefeller Foundation in Peking, China. Of the forty-four doctors, only five were Chinese, along with twelve Chinese “girls” trained in nursing.38

San Francisco Chinese Hospital. Photo by Rachel So, July 2011.

Following the hospital’s opening, the 1930s and 1940s marked an “extraordinary switch from demonizing San Francisco’s Chinese residents to assisting them as deserving citizens.”39 Concurrently, Chinatown’s association with disease and vice transformed to a family-friendly tourist destination for white, middle-class Americans. This transformation was dependent on public health reform, but also necessitated the retention of an alien otherness.40 The Chinese Hospital, therefore, along with other charitable support institutions, not only reshaped the physical geography of Chinatown, but its social geography as well.41

Whereas the city’s first Euro-American hospitals and associated medical practices mediated normalcy, citizenship, and reinforced a racialized social order, the Chinese Hospital mediated a prescribed assimilation process that necessitated a desire from Chinese residents to acculturate to “American” norms, values, and standards of living—while never acquiring the ability to be seen as individuals and receive the full benefits of citizenship. For instance, Chinese Americans struggled to find housing outside of Chinatown because of racially restrictive housing covenants. And even when these covenants lost their legal authority in 1948, Chinese Americans continued to be victims of lawsuits and overt acts of violence.42 The particularly incessant disease of racial prejudice had so effectively centered racial difference in the body, social habits, and architectures of Chinese Americans (amongst other racialized groups in the United States), that they could never quite escape a racialized group identity. While the Chinese hospital was, in theory, a material and symbolic victory for the Chinese community, the racial ordering of immigrant groups and the construction of normality ultimately evolved synchronous with public health reform and advances in hospital design.43 The conditional acceptance of a Chinese community residing within the city, then, was predicated on an architectural cleansing, a prescribed cultural assimilation, and a commodification of San Francisco’s largest non-white immigrant enclave.44

Gray Brechin, Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 29.

Ibid., 30. Quote cited from Emil Bunje and James C. Kean, Pre-Marshall Gold In California (Sacramento: Historic California Press, 1983; reprint of 1938 edition), 44.

See Pekka Hämäläinen and Samuel Truett, “On Borderlands,” The Journal of American History 98, no. 2 (2011): 338–61. Californios can be described as an ethnically mixed group of settlers that lived for several generations in California and descended from Spanish colonizers, African slaves, and Native Americans. For more information see Ryan Reft, “From Alta California to American Statehood: Race, Change, and the Californio Pico Family,” in East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte, eds. Ryan Reft et al. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2020), 37–48.

For a thorough accounting of how racist ideas evolved in the United States, see Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (New York: Nation Books, 2016).

The state’s 1852 census, conducted to supplement the federal 1850 census, used “color” as a category and assigned individuals to either white, negro, mulatto, and domesticated Indians. Most Native Americans in California and the United States, however, were not included in census reports prior to 1900. For a discussion of how race functioned in the first state and local laws of California, see Shirley Ann Wilson Moore, “‘We Feel the Want of Protection’: The Politics of Law and Race in California, 1848–1878,” in Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California, eds. John F. Burns and Richard J. Orsi (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), , 96–125.

For a full account of the Chinese in San Francisco and the blame and stigma they experienced with regards to disease, see: Susan Craddock, City of Plagues: Disease, Poverty, and Deviance in San Francisco (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 10; Guenter B. Risse, Plague, Fear, and Politics in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012); and Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

Mitchel Roth, “Cholera, Community, and Public Health in Gold Rush Sacramento and San Francisco,” Pacific Historical Review 66, no. 4 (November 1997): 527–551.

Ibid., 531. Quote cited from James R. Garniss and Hubert Howe Bancroft, “The Early Days in San Francisco,” 1877, Bancroft Library.

Ibid., 529.

Ibid., 532.

John Morrill Bryan, Robert Mills: America’s First Architect (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001). Mills is best known for his designs in Washington, D.C. including the Washington Monument, the Department of Treasury Headquarters, and the Post Office Headquarters, to name a few. He was the first official architect and engineer of the federal government.

See John Woodworth, First Annual Report of the Supervising Surgeon of the Marine Hospital Service of the United States: For the Year 1872, Containing a Brief Historical Sketch of the Service from the Date of Its Organization in 1798 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1872), cited in Norman E. Tutorow, “A Tale of Two Hospitals: U.S. Marine Hospital No. 19 and the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital on the Presidio of San Francisco,” California History 75, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 154–169.

“The Marine Hospital: Description of the New Buildings—The Pavilion Plan to be Carried out,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 10, 1874.

Tutorow, “A Tale of Two Hospitals,” 165.

Jeanne Kisacky, Rise of the Modern Hospital: An Architectural History of Health and Healing, 1870–1940 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017), 4.

“Five Miles of Wire: For the French Hospital One of the Most Extensive Jobs of the Kind Ever Undertaken Here,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 11, 1894.

“New German Hospital Viewed from Noe Street: It Will Cost Four Hundred Thousand Dollars and Be the Finest Institution of Its Kind in the West,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 1, 1904.

John B. C. Saunders, “Geography and Geopolitics in California Medicine,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 41 (1967): 293–324, cited in Guenter B. Risse, “Translating Western Modernity: The First Chinese Hospital in America,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 85, no. 3 (2011): 413–47.

Shah, Contagious Divides, 3–4.

California State Board of Health, First Biennial Report of the State Board of Health of California for the years 1870 and 1871 (Sacramento: D.W. Gelwicks State Printer, 1871).

Ibid., 9.

Ibid., 44–46.

Ibid., 47. Coolie was a term that was originally assigned to unskilled indentured workers from South Asia and China that Britain exported to their colonies—largely following the abolition of slavery in the British Empire.

See Joshua S. Yang, “The anti-Chinese Cubic Air Ordinance,” American Journal of Public Health 99, no. 3 (2009): 440.

Craddock, City of Plagues, 10.

Ibid., 11. This term is used to describe how geographic spaces, like Chinatown, can be pathologized through the lens of disease and deviance.

Several books and articles have been written on the exclusionary laws that targeted Asian migration to the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first U.S. law that excluded an entire ethnic group from immigrating to the U.S.

Risse, “Translating Western Modernity.”

Ibid., 413–419.

Philip P. Choy, San Francisco Chinatown: A Guide to Its History & Architecture (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2012), 44–45.

Shah, Contagious Divides, 152–153.

Sara Anne Hook, “You’ve got mail: hospital postcards as a reflection of health care in the early twentieth century,” Journal of the Medical Library Association 93, no. 3 (2005): 386–393.

Beatriz Colomina, Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994).

Shah, Contagious Divides, 226.

Yi-Ren Chen, “Chinese Hospital: A Study of San Francisco’s Chinatown Attitudes towards Western Medical Practices at the Turn of the Century,” Herodotus 16 (Spring 2006): 69–83.

“First Chinese Hospital Ready to Open: Chinatown to Celebrate Big Forward Step,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 19, 1925.

“First Chinese Hospital Ready to Open.”

Shah, Contagious Divides, 2.

Ivan Light, “From Vice District to Tourist Attraction: The Moral Career of American Chinatowns, 1880–1940,” Pacific Historical Review 43, no. 3 (1974): 367–94.

Shah, Contagious Divides, 208.

Ibid., 246-247. Racially restrictive covenants date back to the nineteenth century in the United States, but were especially used in the early to mid-twentieth century. They were deemed unconstitutional in 1948 in the Supreme Court ruling Shelly v. Kraemer (1948). See Eli Moore, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri, Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area (Berkeley: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at UC Berkeley, 2019); Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York and London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017).

Ibid., 252–253.

Ching Lin Pang and Jan Rath, “The Force of Regulation in the Land of the Free: The Persistence of Chinatown, Washington D.C. as a Symbolic Ethnic Enclave,” in The Sociology of Entrepreneurship (Research in the Sociology of Organizations 25), eds. Martin Ruef and Michael Lounsbury (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2007), 191–216.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.