In the March 1923 issue of National Geographic, a sketch of a tired-looking businessman invites the reader to the Tucson Sunshine-Climate Club. In the accompanying text, Benj. Lowe—the archetype of the tired, busy, urban, white businessman—attempts to coax all the other Benj. Lowes out there on the East Coast to recover from their unhealthy lifestyles by spending some time in Tucson, Arizona:

That night, for the first time in his hard-working, rushing life, Lowe came to himself. No vacations for ten years. Heavy responsibilities. Making money? Yes. Now on the verge of breakdown. What was it all worth, anyway?

And then his eyes fell on a booklet his worried wife had sent for. It was “Man-Building in the Sunshine-Climate.” …Perhaps you, like Lowe, may find in “Man-Building in the Sunshine-Climate” the clue to robust health.1

This form of health tourism began to appear in journal and newspaper advertisements not long after Tucson was originally incorporated as a city, in 1877. A promotional item published in the Arizona Daily Star in 1890 even went so far as to designate Tucson a place to cure serious pulmonary diseases.2 The rhetoric in these advertisements often framed the Sonoran Desert as “empty,” a place to be “discovered,” as if the Western lands of the continent had remained unoccupied and untouched all along. The process of “Man-Building” advertised by the Sunshine-Climate Club, therefore, carries a double meaning: building oneself and building one’s environment.

Tucson Sunshine-Climate Club, “When Benj. Lowe came to himself,” National Geographic 43, no. 3 (1923): 372.

With the proliferation of advertisements in magazines such as Ladies Home Journal and Journal of American Medical Association, a large number of sick tourists looking for an environmental cure arrived to discover what the desert could offer. Thus, an architecture to house and cure disease became the vision upon which Tucson and many other desert cities in the region, such as Phoenix, thrived. Throughout the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century, hospitals, sanatoria, health resorts, and other structures dedicated to medical treatment multiplied throughout the city of Tuscon, dominating both sick and healthy bodies alike. These buildings were not in isolation, in the manner of nineteenth-century sanatoria in Europe or New England. Instead, they were open and integrated into the urban fabric, embracing the environment and utilizing the restorative properties of the climate as much as possible.

These buildings positioned the sick as the agents of a new form of settler colonialism, advancing the nation’s wider aims to displace and outnumber indigenous communities. At the same time, the architectural strategies employed worked to hide not only the injustice and violence of these territorial transformations, but also the historical signs of settler occupation and war in the previous century. To that end, pulmonary diseases (including tuberculosis) were a medical condition as well as an environmental construct, one inscribed with lifestyle, class, and racial asymmetries in its diagnosis and treatment.3

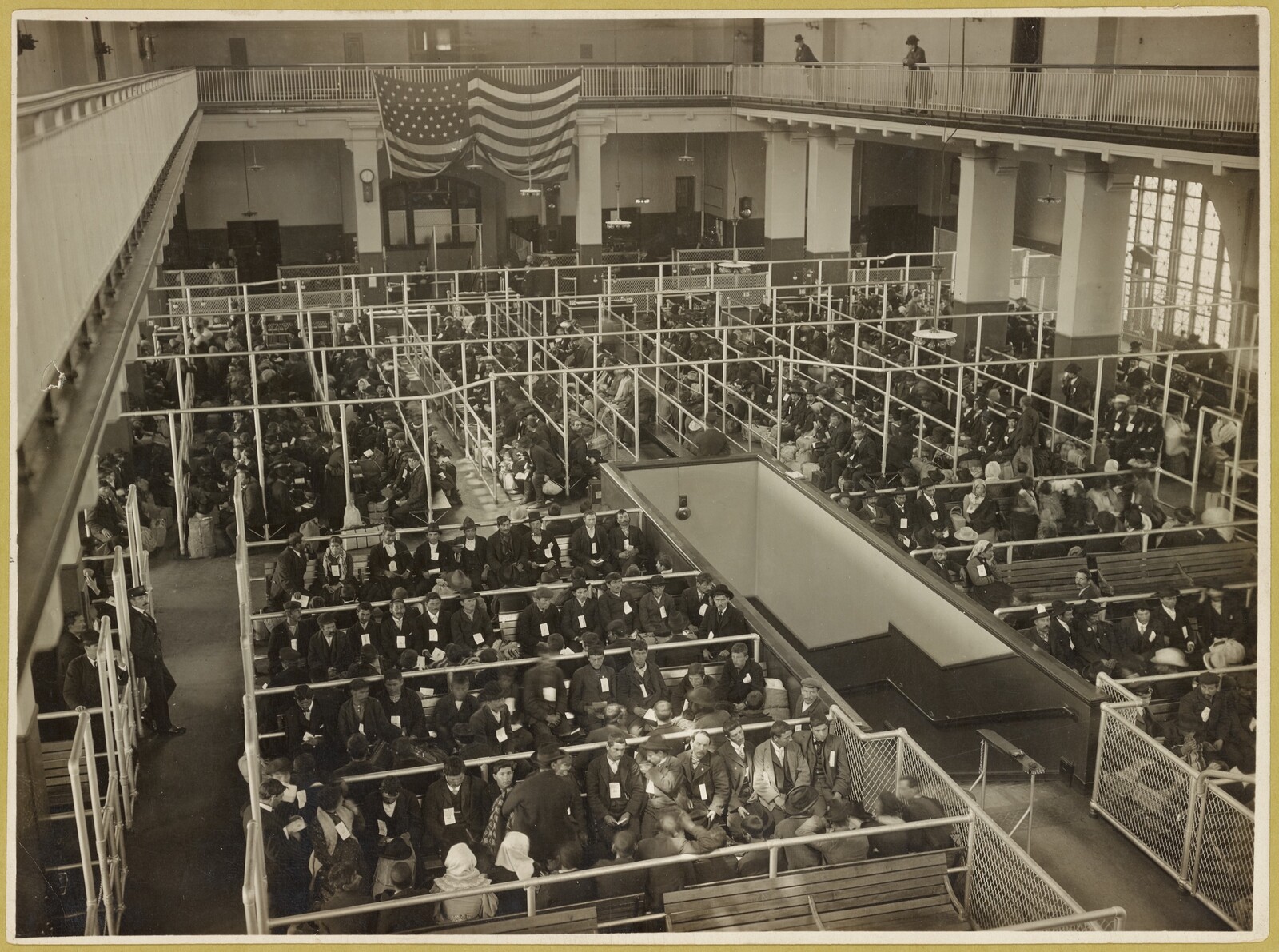

In the late nineteenth century, upstate New York was among the most popular destinations for pulmonary health pilgrimages. With the opening of the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1880, however, towns with dry climates—whose “pure and dry air … was not subject to severe seasonal changes”—started bringing in crowds.4 Historian Gregg Mitman identifies the railroad network as the catalyst that transformed Tucson from a frontier settlement into a city sustained by health tourism.5 Tucson reached its peak as the “health capital” during the 1930s, when the city’s roughly 30,000 residents were joined by about 10,000 health tourists visiting its twenty-one sanatoria, four hospitals, and four luxury hotels during the peak season.6

With the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1882, isolating patients and managing their access to the open air emerged as the desired architectural condition for treating tuberculosis.7 Sanatoria proliferated not only in Tucson but throughout the continent, and manuals such as Tuberculosis Hospital and Sanatorium Construction, published by the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis in 1911, provided construction guidelines for a new typology based on the modernist understanding of hospitals with an emphasis on integrated terraces and balconies for greater access to the open air.8

By 1928, Tucson’s planning and zoning commission had developed a new zoning system for such developments. Spatial buffers were instituted for sanatoria to ensure proper ventilation and isolation, dramatically altering the density and porosity of the city. In a residential neighborhood, for example, sanatoria had to be “set back 200 feet from the property line” and could only occupy “20 percent of the lot.”9

The strict design and planning regulations for sanatoria curbed the rise in new institutions and eventually led to a stop in their construction. Sanatoria quickly became a refuge only the rich could afford, whereas the poor, seduced by the same advertisements, traveled to the outer edges of Tucson and settled in temporary establishments referred to as “tent cities.”10 The lightweight fabric structure of tents, chosen for its low cost and ease of assembly and disassembly, put the patient in constant connection with fresh air. However, the tents were often inhabited by patients and their families with only a small number of volunteers providing care, and their density was surreptitiously conducive to spreading the disease.11

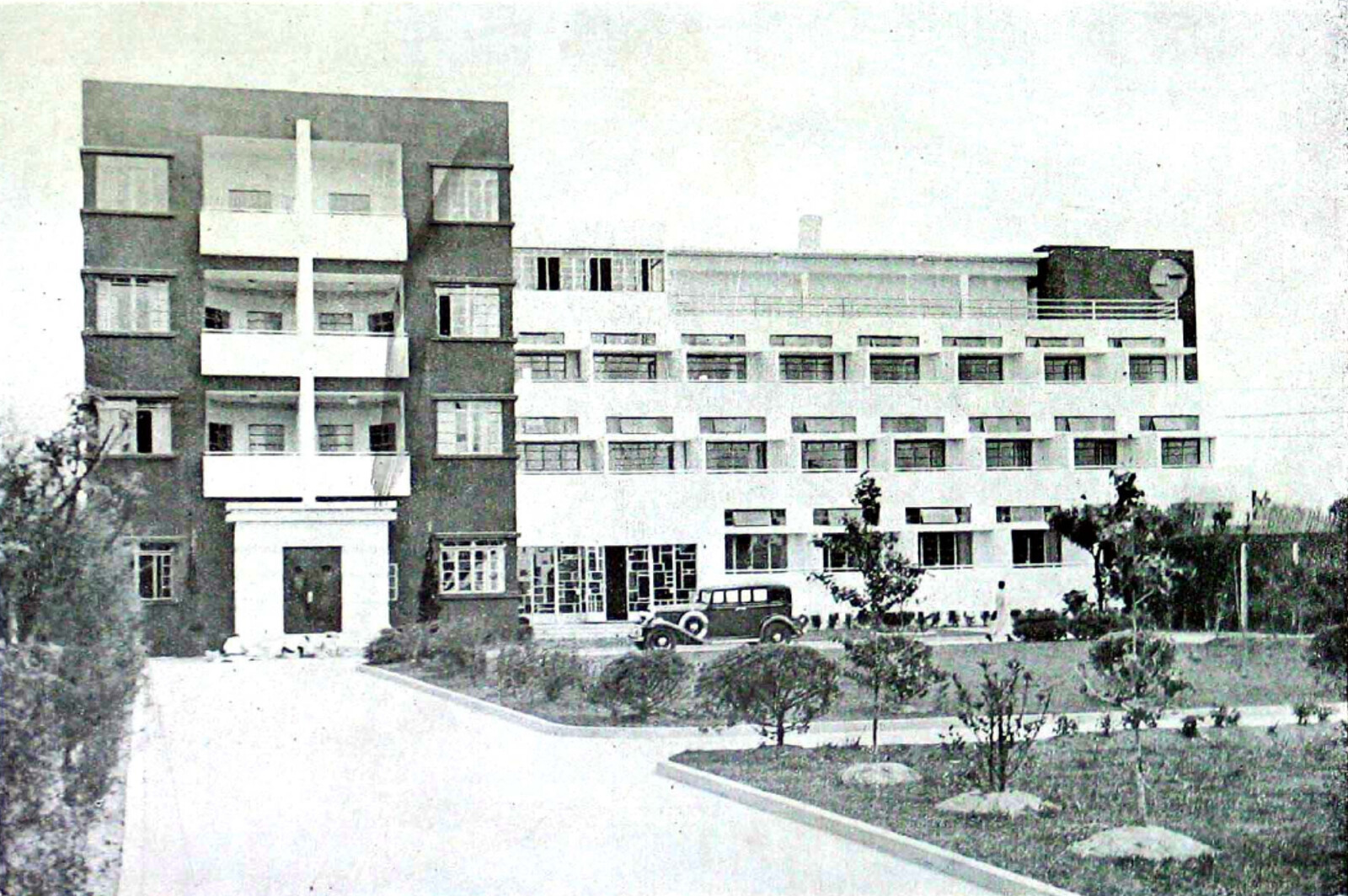

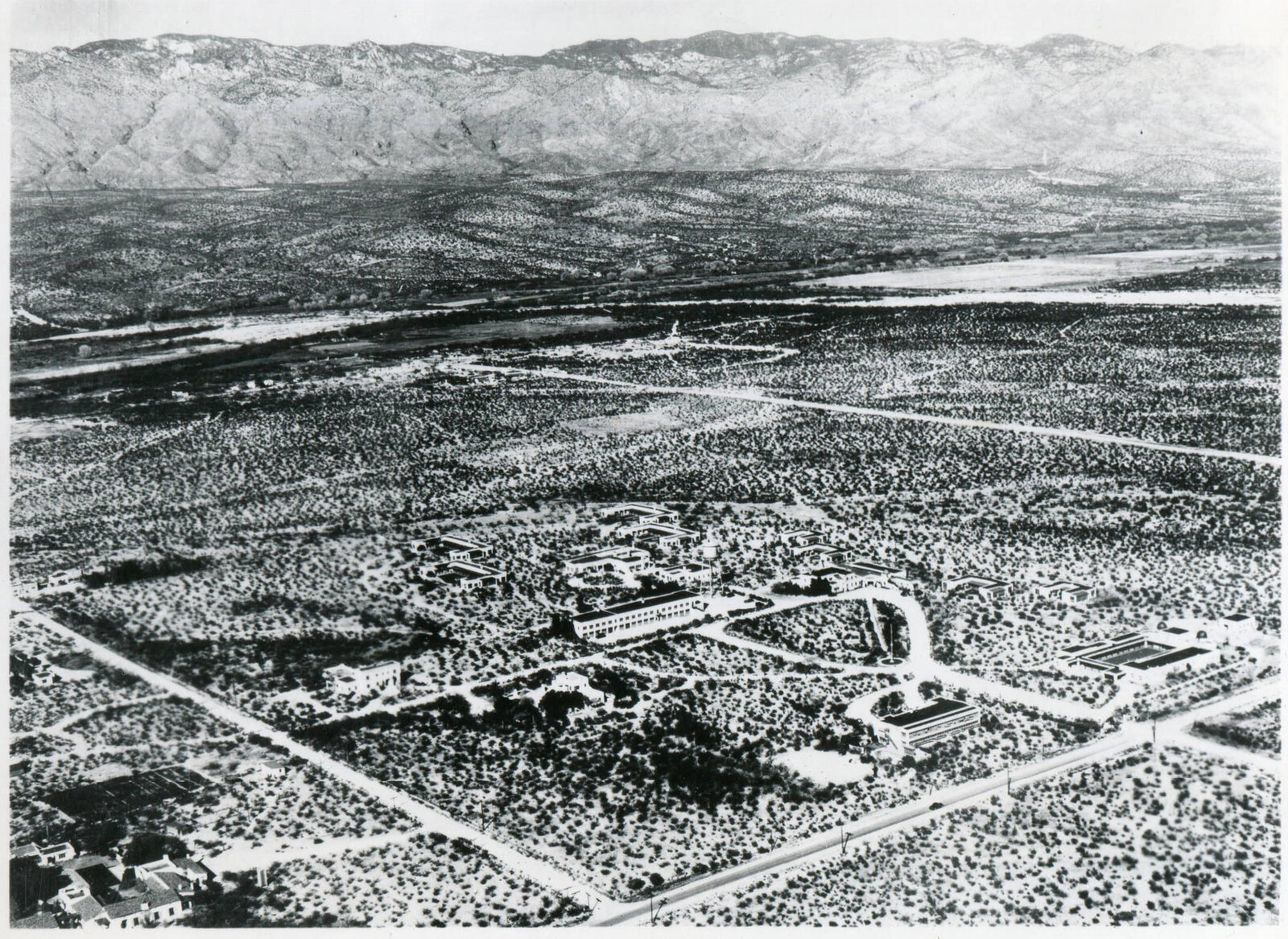

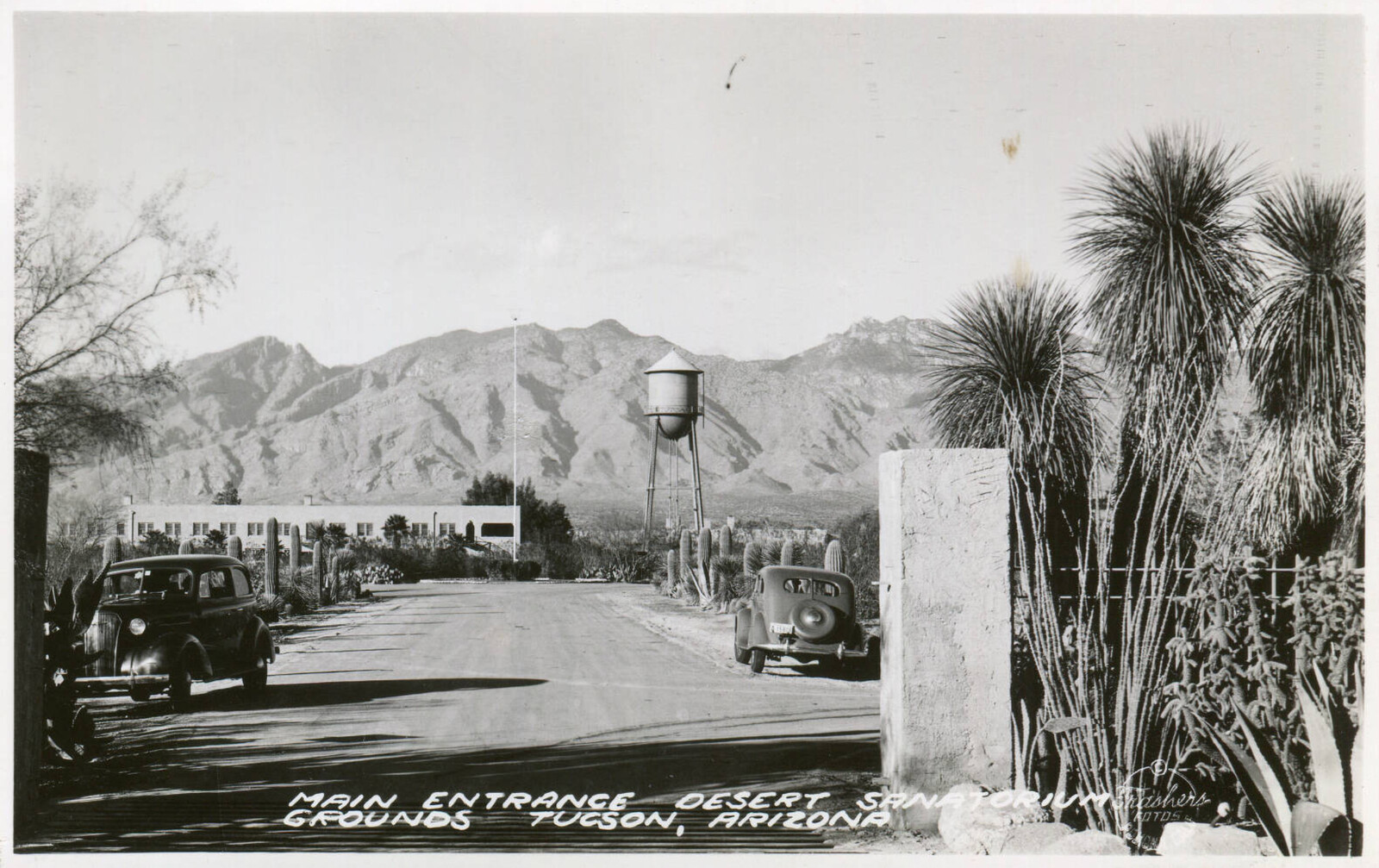

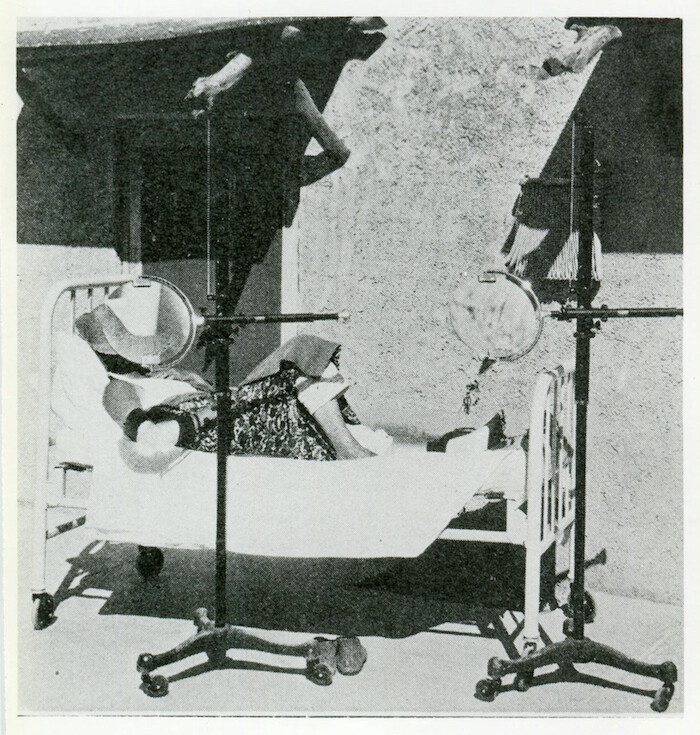

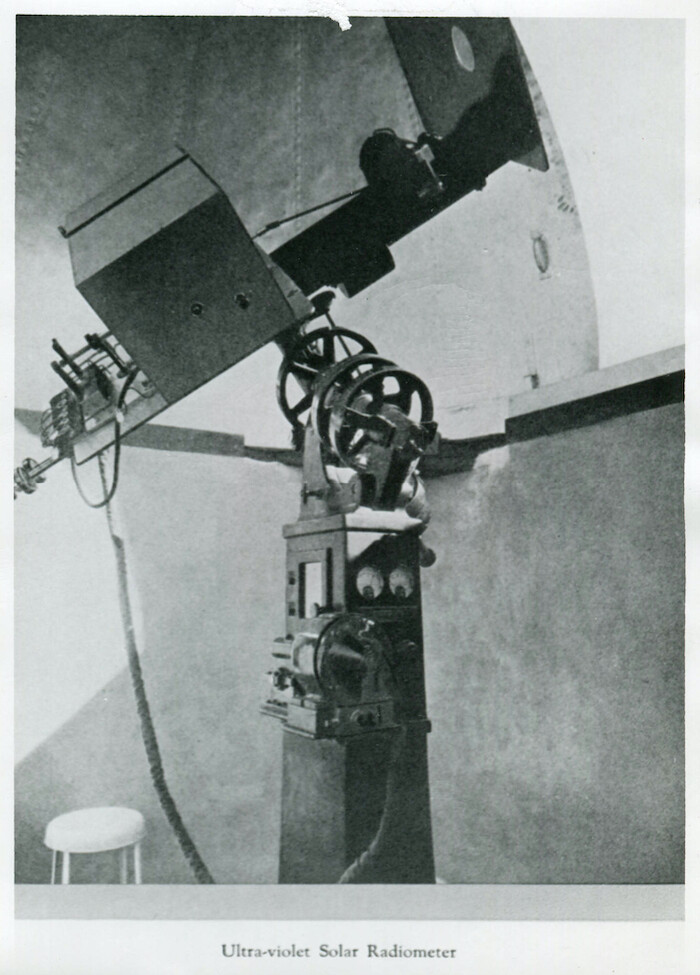

Tucson’s Desert Sanatorium was a massive complex of eleven buildings built in 1926 spread out over 160 acres. Designed by local architects Henry O. Jaastad and Annie Rockfellow, the Desert Sanatorium could care for 120 patients with thirty staff, and hosted prominent physicians from around the country. The main treatment method of heliotherapy, or therapy with sunlight, was achieved through the integration of high-tech machines into the architecture.12 Telescopic devices called radiometers were housed on the roof of the main hospital building, channeling and directing sunlight through small lenses into the treatment rooms and sunbaths below. The sanatorium’s research center, hospital, and nurse’s residences were scattered across the site for increased sun exposure and ventilation in the interstitial patios, courtyards, and gardens.

Aerial view of the Desert Sanatorium, 1930. Courtesy of Arizona Memory Project.

A postcard of the Desert Sanatorium, year unknown. Courtesy of Arizona Memory Project.

An arthritis patient receiving Thezac Lens Therapy, ca. 1920s. Courtesy of Arizona Memory Project.

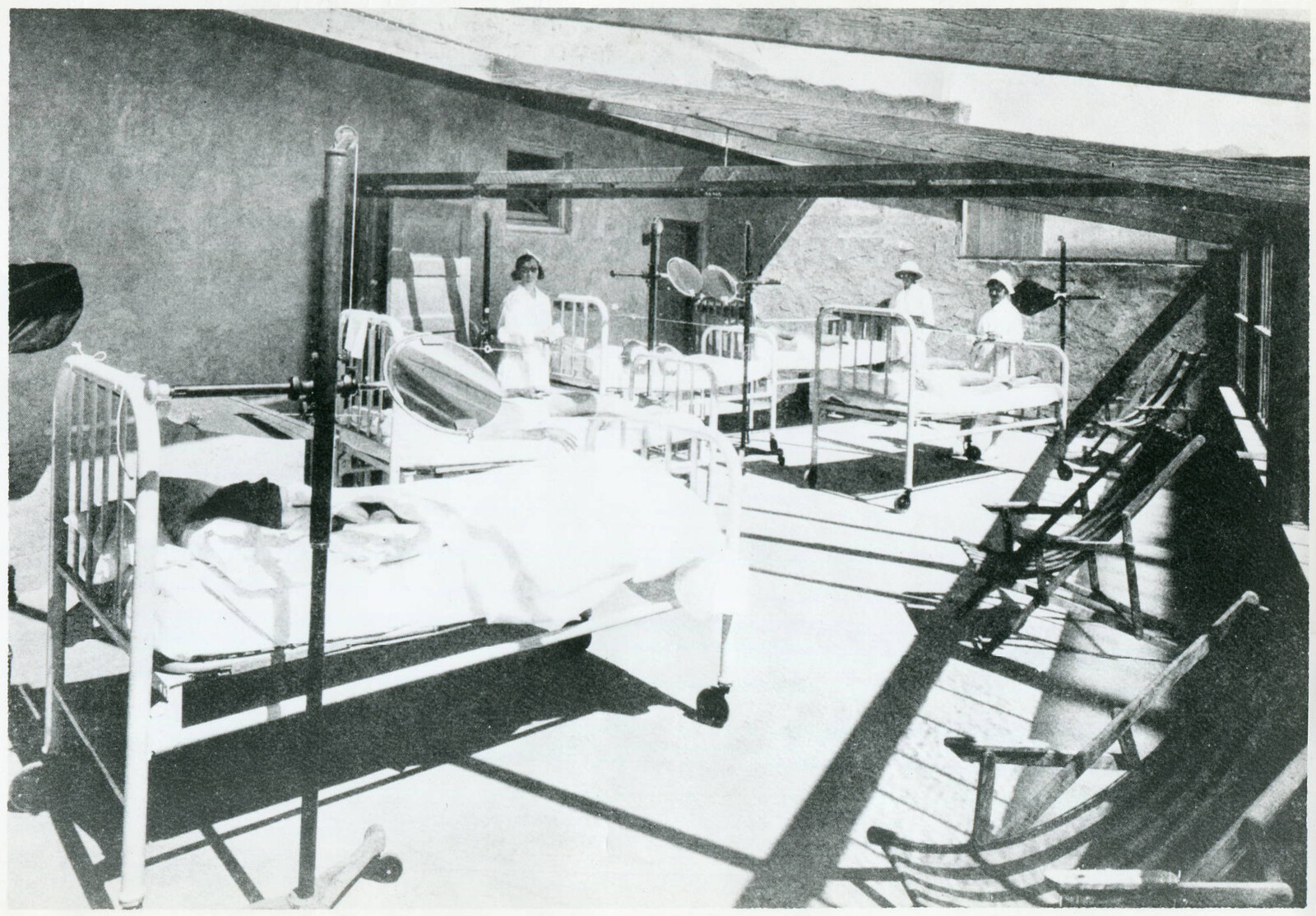

Patients in beds accompanied by medical staff recieving general helio therapy, 1927. Courtesy of Arizona Memory Project.

Ultraviolet radiometer, 1926. Courtesy of Arizona Memory Project.

One of the two Zuni Dining Rooms in the Desert Sanatorium, 1929. Courtesy of Arizona Memory Project.

Desert Sanatorium patient room, 1929. Courtesy of Arizona Memory Project.

Aerial view of the Desert Sanatorium, 1930. Courtesy of Arizona Memory Project.

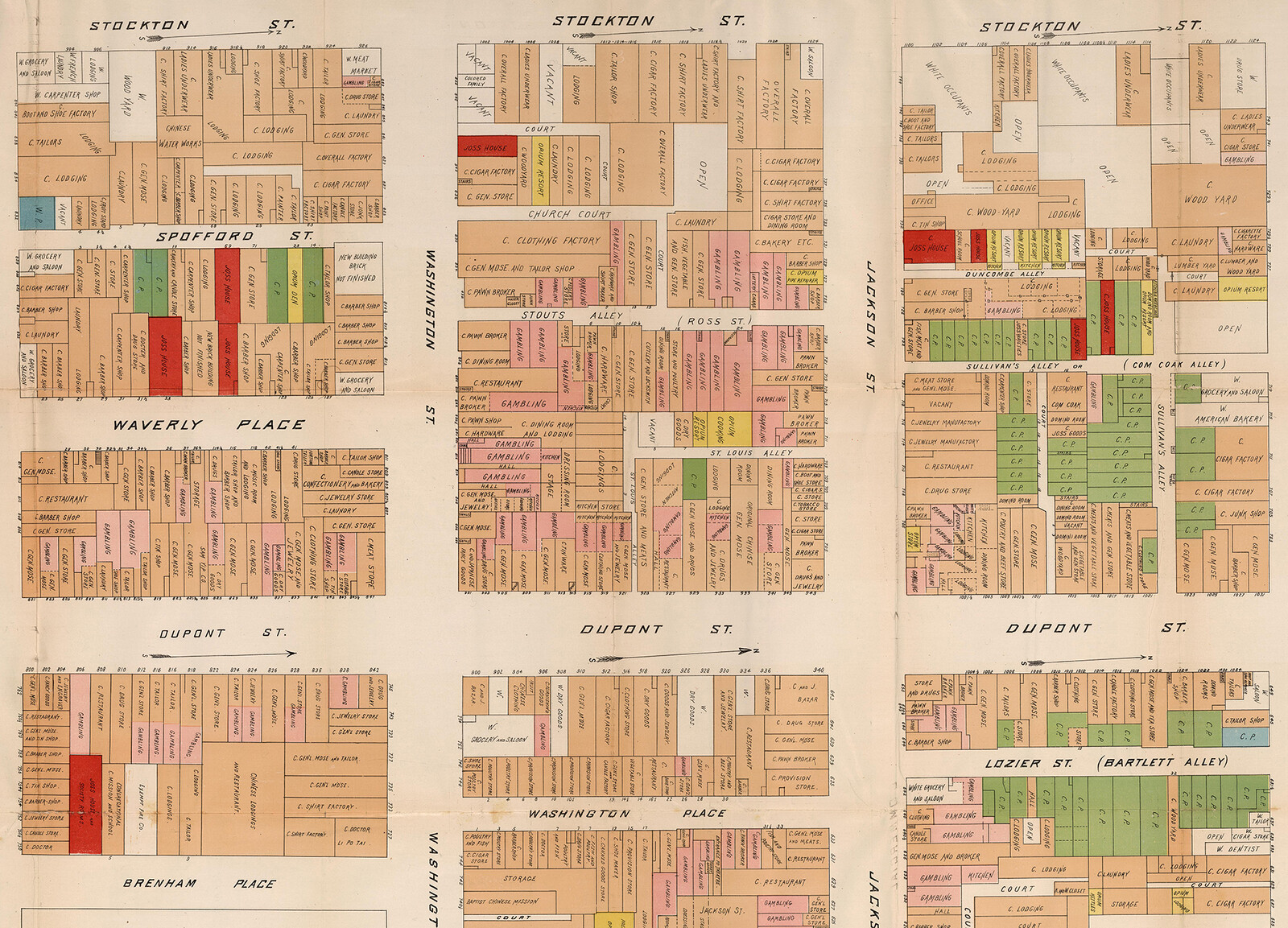

Inside the main treatment building, a functionalist design separated the patient quarters from the nurses’ rooms with a main circulation corridor, thus dividing the spaces of care-giving and care-receiving. Each patient’s room was annexed to a small wooden balcony visible on the façade. Wet spaces were tiled and interiors white-washed, with baseboards curving away from the walls to prevent dust from settling on their surfaces. Window openings or balconies were carved out from the massive, Pueblo-style exterior walls. The Pueblo style also appears in the interior common spaces as Navajo carpets, mural reproductions, and quilts. Patient’s rooms were named after native tribes such as Pima, Papago, and Navajo. Furthering this intended “embrace” of the desert’s cultural heritage, the sanatorium even provided tours for patients to visit indigenous communities in Grand Canyon as part of its leisure amenities.13 These tours sparked the tourists’ imagination of an idealized healthy native body living in the desert landscape.

The appropriation of indigenous culture and symbols persisted in the visual language of the Desert Sanatorium. One patient handbook came with a postcard featuring an image of a highly cultivated Navajo garden, and a description of the Sanatorium’s services and facilities adorned with sketches of a “teepee,” “rain cloud,” “thunderbird tracks,” “broken arrow,” “mountain range,” and “bear track.”14 The symbol of eagle feathers is placed alongside the welcome note by the director to denote his status as “chief” of the complex. The last page of the handbook even contains a personal message from the illustrator, in which he wishes that “each little figure brings happiness … and a very quick recovery. May the Great Spirit Bless and Protect you.”15

Despite the generous application of native iconography and mythology in the sanatorium’s literature, few measures were taken to actually care for the infected people in local indigenous communities. By the early twentieth century, indigenous communities, along with other poor minority groups in Arizona had the highest rate of tuberculosis in the region.16 The Indian Bureau only began to take measures— such as building Indian sanatoria next to Indian schools in order to serve indigenous groups—after the rise of sanatoria and the spread of the disease through the vectors of sick tourists to native populations. These facilities, such as Phoenix East Farm Sanatorium, were run by volunteers and were drastically underfunded and underequipped compared to the Desert Sanatorium and other tourism hospitals.17

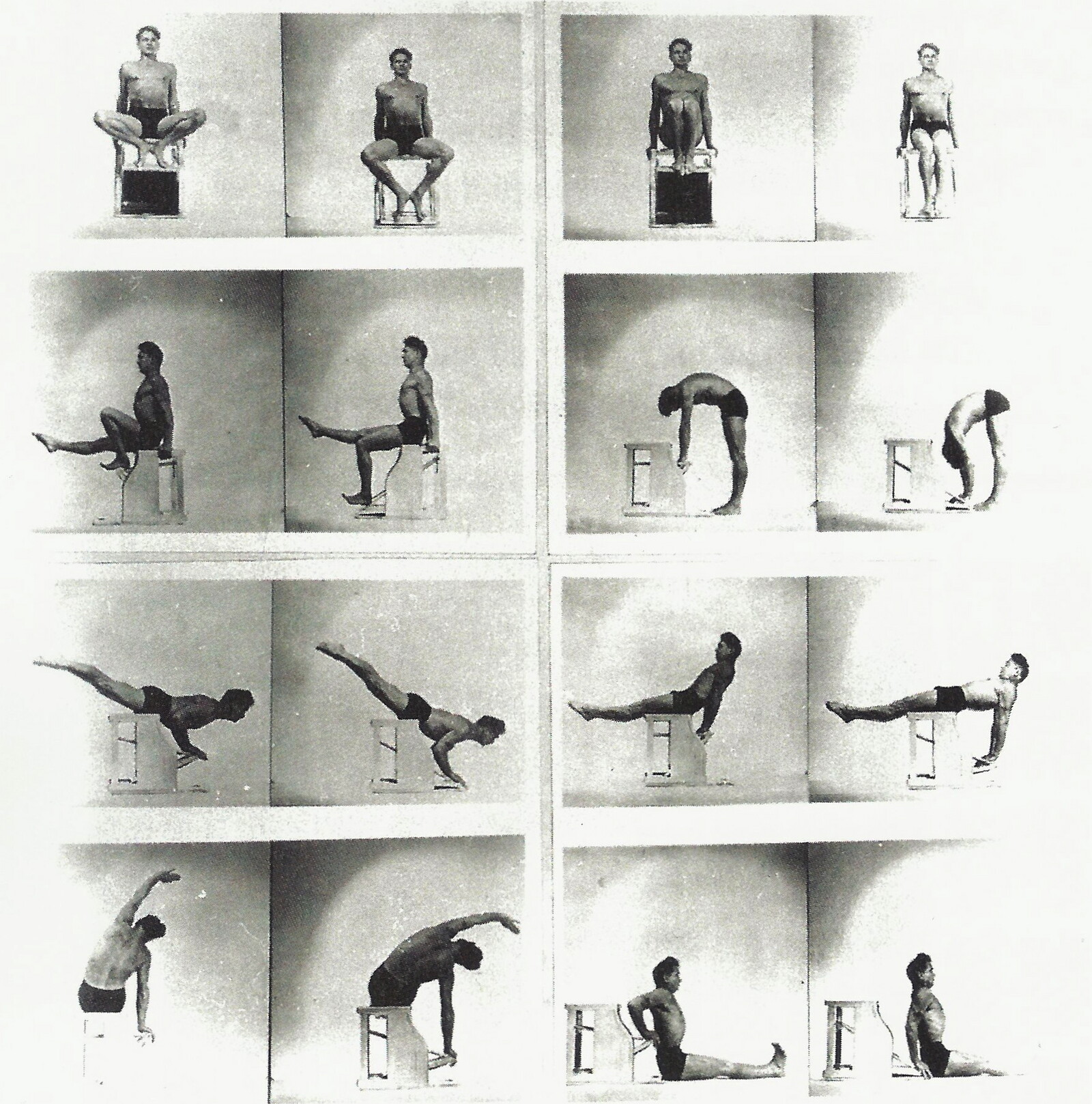

In the absence of governmental provision of the necessary services to treat tuberculosis in native populations, the Carlisle Indian School dedicated an issue of The Red Man magazine to provide news and guidelines to counter the disease. After an introduction on the contagion of tuberculosis among native communities, it overviews the work already being carried out in Indian sanatoria. These analyses are accompanied by photographs of the architectural conditions of the buildings. In order to curb the severity of the disease, the articles make several suggestions, spanning from building more hospitals to teaching individuals proper self-hygiene.18 The issue further suggests the American Indians whose lifestyle shifted from the “more sanitary teepee to the one and two-room box house” could not keep up with hygiene.19 The magazine sought to enable the “medicine man” to cure the sick and train the indigenous population to undertake this job, but not, however, without yielding to an institutional form of governmentality. The narratives attempted to make the indigenous body productive against the pervasiveness of the disease. It yielded to the top-down institutional logic of controlling bodies by prescribing protocols.

The entanglement of disease, climate, bodies, and institutions in the southwest United States in the early twentieth century is reminiscent of earlier forms of injustice and violence perpetrated by settler colonialism in the same lands. The disease, then, is not only a medical construct, but is firstly an environmental construct shaped by the climatic imaginaries which, in turn, shapes the urban context. Secondly, it is a social construct that privileges a certain lifestyle and class through its contagion and access to treatment. Lastly, it is a political construct, as it perpetuates the asymmetrical relationship between communities in the eye of the government and institutions. Amid these racial and economic imbrications, architecture is instrumentalized to facilitate institutional agendas. To understand tuberculosis here means to make visible the persisting colonial logic. Architecture perpetuates violence against the figure of the other.

“Tucson Sunshine Climate Club,” National Geographic Magazine 43, no. 3 (1923): 372.

“Many hundreds of people who come here in the last stages of pulmonary troubles recover in a short time so they are enable to engage in business.” From “Tucson as Sanitarium,” Arizona Daily Star, January 7, 1890.

Recent scholarship on epidemics has framed disease within a political or social sphere, especially in environmental history. For instance, historian Chris Gratien analyzes malaria as a “biophysical pathology of the environment.” Gratien acknowledges that the study of an epidemic and settlement “begins to shed light on the non-human factors, from climate and geological processes to animals and microbes, in historical events and why they matter for the history…” which leads to embracing “perspectives of political ecology that employ a post-positivist understanding of nature and the production about it, which views them as inseparable from social relations of power.” See Chris Gratien, “The Ottoman Quagmire: Malaria, Swamps, And Settlement in The Late Ottoman Mediterranean,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 49, no. 4 (2017): 584–585. Meanwhile, historian Alan Mikhail investigates the plague as an essential component of the “environment (as one component of famine, food, draught, inflation and revolt) and of life rather than as an external threat.” See Alan Mikhail, Water on Sand: Environmental Histories of the Middle East and North Africa (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 111.

Gregg Mitman, Breathing Space: How Allergies Shape Our Lives and Landscapes (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 104.

Ibid., 94.

Ibid., 110.

Until the late nineteenth century, pulmonary diseases were thought to be caused by environmental factors, hence the sick patients were not necessarily isolated from one another. They all sought cure in nature.

Through a variety of case studies, mostly from the northeast United States, the manual attempted to standardize spatial divisions, finish materials, economic costs, and expenditures. See Thomas Spees Carrington, Tuberculosis Hospital and Sanatorium Construction (New York: The National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, 1911).

Tucson Health Seekers: Design, Planning, and Architecture in Tucson for the Treatment of Tuberculosis for National Register of Historic Places (Tucson: Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation, 2012), E-10.

Mitman, Breathing Space, 110.

The contrast between central concrete sanatoria and peripheral fabric tents manifested social inequality at the scale of the body. As theorized by the sociologist Sara Grineski and her peers: “The production of inequalities can take place at the level of the body… Craddock contends that the production of bodies and disease occur simultaneously with place production and that the three cannot be separated… A sociospatial ‘sorting’ began taking place in the city as poor unproductive migrants with TB were stigmatized and excluded, while the wealthy productive healthseekers were integrated and seen as economically and culturally advantageous.” See Sara Grineski, Bob Balin, and Victor Agadjanan, “Tuberculosis and Urban Growth: Class, Race and Disease in early Phoenix, AZ,” Health & Place 12 (2006): 604.

The treatment method was modeled after Dr. August Rollier’s clinics in the Swiss Alps, which literally directed sunlight onto the skin of TB patients. See Tucson Health Seekers, E-18.

For quote from Jennifer Lestvik, see Bethany Barnes, “Historical status sought for sites TB patients used,” Arizona Daily Star, June 21, 2012, ➝.

Tucson Medical Center, Dear Patient (Tucson: Tucson Medical Center, year unknown).

Tucson Medical Center, “Your Artist,” in Dear Patient (Tucson: Tucson Medical Center, 1961–1962). Another patient handbook neutralizes the violence of settler colonialism, describing the native lands as if the white settlers had found them empty and destroyed: “This desert mesa was the stage where throve and died a high prehistoric culture. It still holds the remain of pueblos that were ruins centuries before the white man set foot on the Western continent. The Franciscan friar and the Conquistador trod the Santa Cruz valley when the founders of Jamestown and of Plymouth were still unborn. For archaeologist and historian alike, this desert country is a mine of interest.” The Desert Sanatorium and Institute of Research (Tucson: Desert Sanatorium, 1932), 7.

Grineski, Balin, and Agadjanan, “Tuberculosis and Urban Growth,” 607–609.

Robert Trennert, “The Federal Government and Indian Health in the Southwest: Tuberculosis and Phoenix East Farm Sanatorium, 1909–1955,” Pacific Historical Review 65, no. 1 (1996): 83.

Dr. F. Shoemaker, “Important Phases of the Tuberculosis Problem,” The Red Man 6, no. 9 (May 1914): 355.

Ibid., 352.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.