1. Pinch Points

I write from the watery, mountainous Pacific Northwest of North America. This is the bioregion that pulses between the tar sands, the gas shales, and the open-pit coal mounts of the fossil fuel interior and the handful of coastal ports that can accommodate the tankships and colliers that carry bitumen, liquified natural gas, and coal to cities across the Pacific. As the zone between the major production and export of fossil fuel materials, the Pacific Northwest is crisscrossed by highways, rail lines, shipping lines, and pipelines for fossil fuel transport and for the transport of equipment to build more oil, gas, and coal transportation infrastructure. These lines and pipelines—actual, contested, and proposed—are critical factors in the future of the climate and in the future of the land and communities they traverse. As such, they are aggressively contested in terms of conflicting property, corporate, human, indigenous, and ecosystem rights.

Recently, I stood with the climate activist and anti-pipeline organizer Maya Jarrad in a cattle pasture in the Umpqua River watershed in southern Oregon, looking toward the surveyed route of the proposed Pacific Connector Pipeline. This is a new pipeline that is planned to run natural gas from Alberta, Canada to the proposed Jordan Cove Natural Gas liquification plant in the Port of Coos Bay, Oregon. Maya pointed to where the above-ground pipeline would drop from the clear-cut ridgeline to the east and to where it would tunnel under a riffle in the creek to our west.

Maya explained that if an organizer wants to obstruct construction of new oil and gas pipelines, the Pacific Northwest is a good place to do that work. Because of the complex mountain ranges and the small number of navigable ports, there are relatively few ways a new pipeline can be routed and few places where an export facility is feasible. This is different from opposing pipeline construction in the Great Plains, she explained, where topography does not pose as much of a challenge to fossil fuel companies. There, if one county or city does not want a pipeline, corporations can just shift the survey one way or another, routing construction through sites that present less resistance.

Accordingly, just as the Pacific Northwest is threaded with the surveyed routes and sites of proposed pipelines and other facilities, it is also dotted with blockades that impede the movement of construction equipment, trains, and ships. In 2015, for instance, Greenpeace protesters on the Willamette River in Oregon blocked the Royal Dutch Shell icebreaker Fennica from its progress to an artic drilling site by rappelling from a bridge, joining hundreds of kayakers who helped impede the ship’s progress from port. In 2020, land defenders used physical blockades and other peaceful delay tactics to impede Coastal GasLink workers from travel on roads in interior British Columbia—including by blocking a road with a gate painted with the word “Reconciliation.” During this same period of blockades and militarized removals of defenders, other land defenders blockaded roads and rail lines across rural Canada in solidarity, effectively shutting down Canadian rail transport. In a slower form of blockade, members of the Oregon Women’s Land Trust have recently been establishing human burials in places that may strategically protect entire watersheds from new pipeline construction. And in early 2021, land defenders in Ontario locked themselves to a flipped car on an Enbridge Line 3 work site access road, and Inupiaq hunters on snowmobiles blockaded the airstrip of a Baffin Island mining operation, temporarily shutting down the 700-person operation—another pinch point applied to linear space, where a small amount of pressure creates a large amount of resistance.

2. Temporal Symmetry

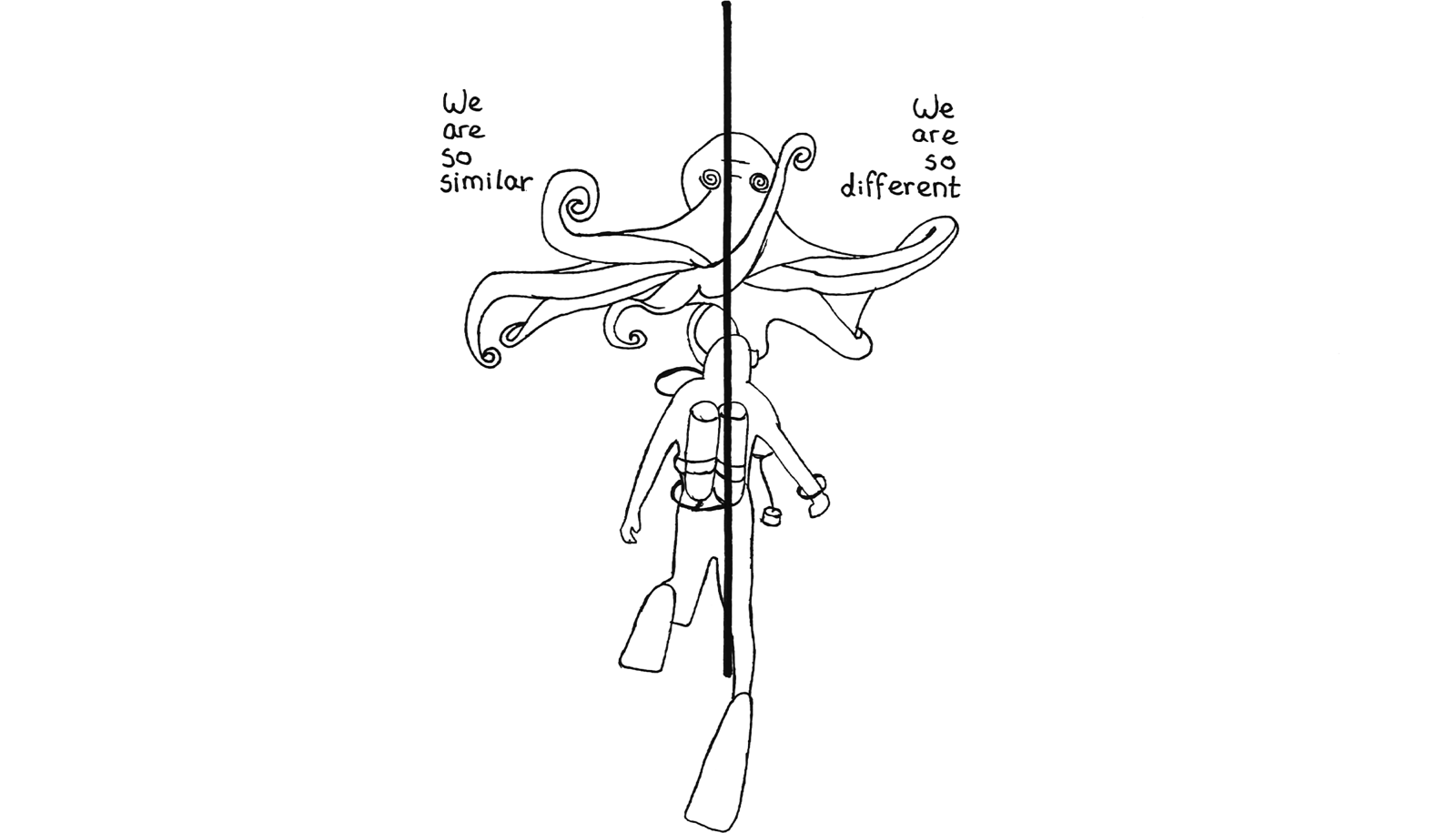

During the introduction to a performance of her rap “Ancestor from the Future” at a 2015 Love Water Not Oil event, artist Allison Akootchook Warden stretched out one of her arms to show the shape of Inupiaq-speaking land running from her hand and home (Alaska) to her ticklish armpit (Greenland). In 2017, I watched Warden introduce her performance of the same rap at the 2017 Nevada Museum of Art opening of the exhibition Unsettled by making a circle of her arms above her head, with her hands almost—but not—touching at the top of the circle. She explained that we are living in that gap between her hands, between the past and the future as represented by the two halves of the symmetrical circle of her arms. Rapping as “Aku-Matu,” Warden performed as a female ancestor, a time-traveling visitor to the future who encourages her “great-great-great-great” to manifest their own destiny. In both the song and in the body-space diagram of time, Warden organized temporal space symmetrically; looking one way around to the “great-great-greats-greats” of the past and looking the other way to the “great-great-greats-greats” of the future.1

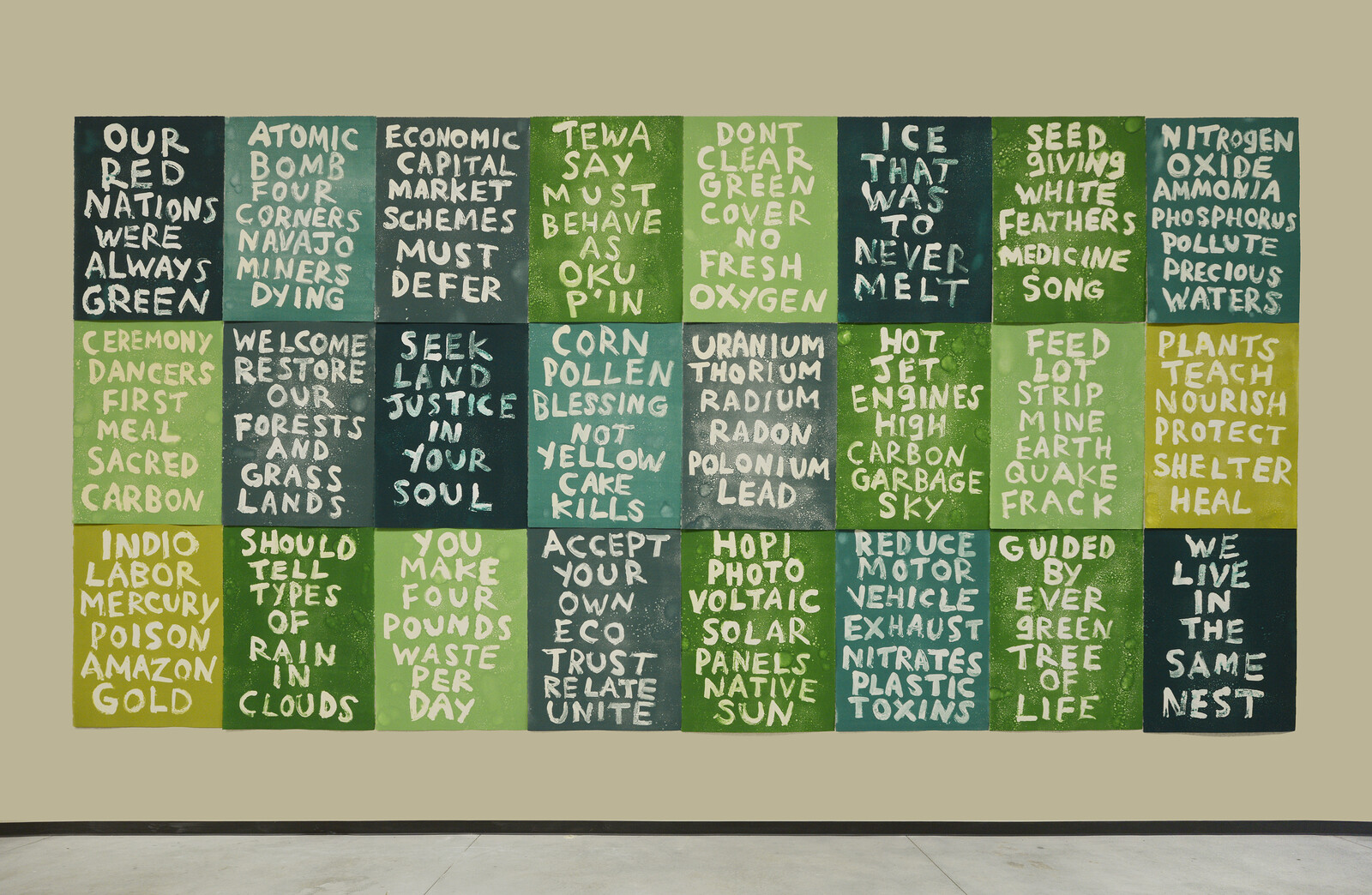

Living this moment, as between Aku-Matu’s two hands, requires looping back to simultaneously apply truth-telling, reconciliation, and joy to the future and to the past. 2020 was a year when it seemed like all of the inconceivable, terrible impacts that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change forecast and graphed—so very tidily—in their assessment reports was coming to pass one after another and all at the same time. Indeed, the moment to address the climate catastrophe is truly urgent. But this catastrophe is not a new one. The kinds of grief and loss that climate change and pandemic disease has brought forth first came to North America with the violent, extractive practices of colonization, settlement, and slavery. As T.J. Demos writes, the emergency is not a modern “we are all in it together.” Rather, he writes, “it has resulted from centuries of colonial pillage, violent environmental transformation, and genocidal destruction, creating and perpetuating profound, systemic injustice.”2

The temporal site of resistance to climate change is therefore simultaneously the past and the future. Grief and survivance in the face of future loss (of liveability, biodiversity) must be matched with grief for and survivance of structures of past loss (of liveability, biodiversity). This temporal symmetry meshes well with a model of time that is neither cyclical nor linear but that editors of the volume Feminist Futures of Spatial Practices posit as “revolutionary time,” or “an alternative temporal mode that rejects patriarchal conceptions of time, for example in distinctions made within philosophy between linear and cyclical notions of time that reflect (gendered) divisions of labor.”

The space and time described in Allison Akootchook Warden’s latest Twitter poem, posted in six tweets in December 2020, is an interconnection of body to the universe, with joy transcending the future and the past. It runs from the size of a cell in the human body, to the infinitely expanding universe, and is simultaneously this moment, that of ancestors, and that of descendants—in terms of renewal, babies, and stars.3 The radical space of this long form poem of joy, as Akootchook Warden describes it, is a different kind of “we are in it together” in which the “we” is the universe and time is infinitely renewing.

3. Material Whole

On my last visit to the Sandy River Bird Blind, located at the confluence of the Sandy and Columbia Rivers in Oregon, fluffy cottonwood seeds in the air were catching thickly, like wool in a comb, on the vertical slats of the blind. The blind itself, one of a number of installations designed by Maya Lin as part of the Confluence Project in the Columbia River Watershed, is a simple platform partially enclosed by these slats and raised above the delta of the Sandy River on steel piers.

The Sandy River flows freely now, after an earthen dam upriver from the pavilion was removed as part of the park design. Now, seasonal floods in the newly free-flowing river channel soak the cottonwood pods and carry them downstream to germinate in everchanging new channels. This is a place where the river is braiding in channels that intersperse the riparian forest so that the water and land make one inseparable whole. Walking under the bird blind structure recently, I did not recognize the shape of the silty ground; it had shifted since I had been there last, moving independently of the structure above me. The structure is supported on piers that anchor forty feet into the ground and that do not depend on the stasis of the earth around them for stability.

On a day without cotton fluff, I can see out through the slats of the blind, and I can hear the blur of insects and birds that share the microclimate and the nutrients of the newly re-grown forest. The willows and the cottonwood smell more like the nearby river than the river itself. Even a stick’s throw from the iconic Columbia River, you cannot see the river from the pavilion. Instead, there is a feeling of being immersed as part of the riparian whole—a whole that is shared by all that is human and more-than-human.

In 2016, a train carrying nearly 100 tanker cars full of oil from North Dakota derailed from its Union Pacific track and caught fire along the tracks about an hour upstream from the delta. The next morning, an oil sheen reflected the sky on the Columbia River. In all, 42,000 gallons of oil were spilled, consumed by fire, and recovered by the city’s sewage treatment plant. Like Lin’s Bird Blind that positions the visitors as part of the living and material whole, the oil train derailment, fire, and spill into the land and river also shows the material of the region, local bodies, and the transported oil as an indivisible, messy human and more-than-human whole.

4. Domestic Space

To oppose the plan of adding a second pipeline alongside the existing TransMountain pipeline and doubling the transport capacity of bitumen from Alberta, Canada to the coast, Secwepemc land and water defenders in Northeastern British Columbia have been building tiny homes on wheels since 2017. These homes are moved by the women-led Tiny House Warriors into strategic locations along the pipeline construction route to assert Secwepemc Law and jurisdiction, and to block access to the sites of future pipeline construction.4

These homes on wheels both do and do not fit into the of the genre of tiny homes. On social media, tiny houses exist in a romanticization of domesticity in a wilderness that appears untouched, at least within the photo frame. The small size and indeterminate vistas of these tiny houses (catering to the bourgeois dreams of the comfortable white nomad in a converted bus or bucolic cabin) gives their subjects purview over large amounts of land. The Tiny House Warriors’ homes are also meant to establish and demonstrate purview over large amounts of land. As Spokesperson Kanahus Manuel said, “the pipeline is one thousand kilometers long … and this is a big place.”5

Unlike the social media posts of most tiny houses that exude safety and bliss, the Tiny House Warrior encampments have been places of conflict. As the encampments physically and symbolically impede the freedom of movement of company workers and equipment to the pipeline man camps, land and water defenders with Tiny House Warriors have been surveilled, harassed, and arrested repeatedly by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. One night in April 2020, three men and a woman drove into the Tiny House Warrior camp near Blue River, British Columbia and according to Greenpeace, “tore down several red dresses that are symbols of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and Two Spirited people.”6 One of these attackers also got into a vehicle owned by Kanahus Manuel and drove it into the tiny house where she had taken refuge. According to Manuel, the primary threats from the pipeline construction come from the construction worker man camps and from the harm of occupation, as measured in missing and murdered indigenous women, drugs, and now COVID-19, all associated with the camps.7

These wood-frame, wood-clad tiny houses on trailer wheelbases have been moved into locations that the Tiny House Warriors describe specifically as an “occupation” at the North Thompson River Provincial Park, British Columbia; as a “blockade” at the Secwepemc village site; as a “permanent village site” at the TransMountain man camp at Blue River, British Columbia; and as an “establishing presence” and “blockade” at Moonbeam Creek on the North Thompson River.8 In a joint statement from Secwepemc and Gidimt’en land defenders, Sleydo’ Molly Wickham, spokesperson of the Gidimt’en Checkpoint, wrote, “We stand with our Secwepemc relatives in their struggle and ask all Indigenous peoples and our allies to stand up for the salmon, the clean drinking water, the animals, and our future generations. We will not let them kill us. We will always be here.”9

“Unsettled,” curated by JoAnne Northrup with Ed Ruscha, Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, August 26, 2017 to January 21, 2018, ➝.

T.J. Demos, “Extinction Rebellions,” Afterimage 47, no. 2 (June 2020): 14–20.

Allison Warden (@AKU_MATU), “I will share my long form poem that I performed today as a thread…” Tweet, December 20, 2020, ➝.

Tiny House Warriors: Our Land is Home, 2020, ➝.

Living Big in a Tiny House, “Tiny House Warriors: Building Tiny Homes To Defend Against Oil Pipeline,” YouTube, September 11, 2017, ➝.

Laura Kenyon, “Violent Attack on the Tiny House Warriors Should Be Publicly Condemned,” Greenpeace Canada, May 4, 2020, ➝.

Living Big in a Tiny House, “Tiny House Warriors.”

Tiny House Warriors, “Tiny House Warriors Arrests,” November 2020, ➝.

“Joint Statement by Secwepemc & Gidimt’en Land Defenders,” Tiny House Warriors: Our Land is Our Home, October 16, 2020, ➝.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.