“Oh, that’s definitely a post.” I didn’t agree, but I posted it anyways. Not because it was done (it wasn’t), but because I was finished.

*

Today we live in a perpetual state of construction of both spaces and people via the “post.” Everything feels cumulative, iterative, chaotic, refined, but never complete. For a new generation of cultural workers, the assessment of quality, relevance, or profit comes through the question: is it ready to post online? Yet, once posted, it’s never the final word. New media has become “habitual media” through its incessant permeation into daily life, slipping into our domestic activities, episodes of consumption, and performance of work.1 Social and professional products become interchangeable, punctuated only by how they can be instrumentalized online. This conflation of interior and exterior is most palpable—and wholly embraced—within “content houses,” a physical manifestation of this performance of habitual labor.

Content houses are a growing typology for digital creators—from macro-influencers to micro-influencers. They first began with a handful of Los Angeles properties, but have now spread worldwide as an industry-backed content creation model. Creators previously held collaboration days at hotels or recreational centers but discovered the efficiency of working and living under one roof.2 Content houses provide digital creators the luxury of having ample space to not only create their own content but also cross-collaborate with one another to maximize their digital footprint. The houses they occupy, from their bathrooms to their driveways, become infamous and identifiable spaces on the internet for all.

The Hype House bathroom, represented through the collection of feeds, as of July 2020. Drawing: Samiha Meem

Social media reproduces and accelerates the effects of individuation and isolation brought by late-stage capitalism. Digital creators are virtual frontline workers in this malaise and are tasked with addressing the gap that has formed in their relationship with others. Many content creators start off by making their material alone in their bedrooms. Their experiences of grappling with the consequences of their exposure, good or bad, happens entirely in isolation. Creators were quick to jump on the content house train, infusing this non-traditional, post-nuclear chosen-family occupation of luxury homes with a sense of urgency. Amidst a universal work culture that otherwise breeds loneliness, the foundational mission of the content house is to reintroduce, and make accessible, a lost intimacy and slippery support.

These paraprofessionals exist on a spectrum of specificity and generality in their occupation of the domestic and the virtual elsewhere.3 Their work is not contained in the traditional relationship between introverted production and extroverted display. Readily socialized, both are immediate and habitually delivered in large quantities, available for constant, compulsive, incessant, endless consumption.4 The elsewhere place they occupy is made up of this ceaseless flow of content and is solely dependent on an immense body of documentative labor to give it shape. The architecture of the content house becomes revealed only through content. How, then, is architecture, and our labor towards it, implicated in the post?

Delivery in Stream

Albeit a physical place somewhere, the content house is not to be mistaken for a literal house. They are not built with brick and mortar, but rather with an endless feed of posts. The “Hype House,” a now infamous content house that predicated the rise of the collaborative typology, is composed of dozens of creators that fluctuates in both people and the temporal properties they occupy. In their construction of posts, it’s evident that members have their own individual autonomy in determining what the content house is; each their own agendas, relationships, and speeds that inform how they represent the house. Not only is each member presenting their respective image of the content house, contained within their own feeds, but they are also contributing to a shared image built through the sum of everyone’s feeds.

As a consequence of the medium, the house only exists as a product of collaborative labor towards an architecture—an architecture that is never complete but always aggregating apropos to completion. A single post has the power to effectively alter the representation of the content house, providing each member equal authority and control. Everyone has their defined role—a musician, actor, make-up artist, videographer, designer, comedian, dancer, philosopher—and together, with respect to each other’s roles, they build the content house. Some move on and others take their place. One lease is up, and another gets signed. At the end of the day, the house creates one digital body. Without clear authorship of the whole, there is no singularly attributed capital gain, but collective ownership and shared rewards.5

A key motivator for pursuing this collaborative typology was to build physical community, and a much-needed emotional support network that is often lost in the individualized, one-sided experience of social media. Functioning in numbers provides safety and reroutes the medium into something humanizing and equitable.6 While this allows for the authorship of the content house to be collective, there is still access to autonomy. Working within their own feeds, and not anonymously under someone else’s name, content creators can receive rewards as individuals for their respective labor—a labor that is explicitly visible. Since the burden of constructing the content house is not dependent on any single member, there is space for different scales of labor quantified by singular posts. This allows for individual recognition to become more accessible without being detrimental to the collective. In fact, it only strengthens it; one person’s virality uplifts everyone within the digital body.

Post in Production

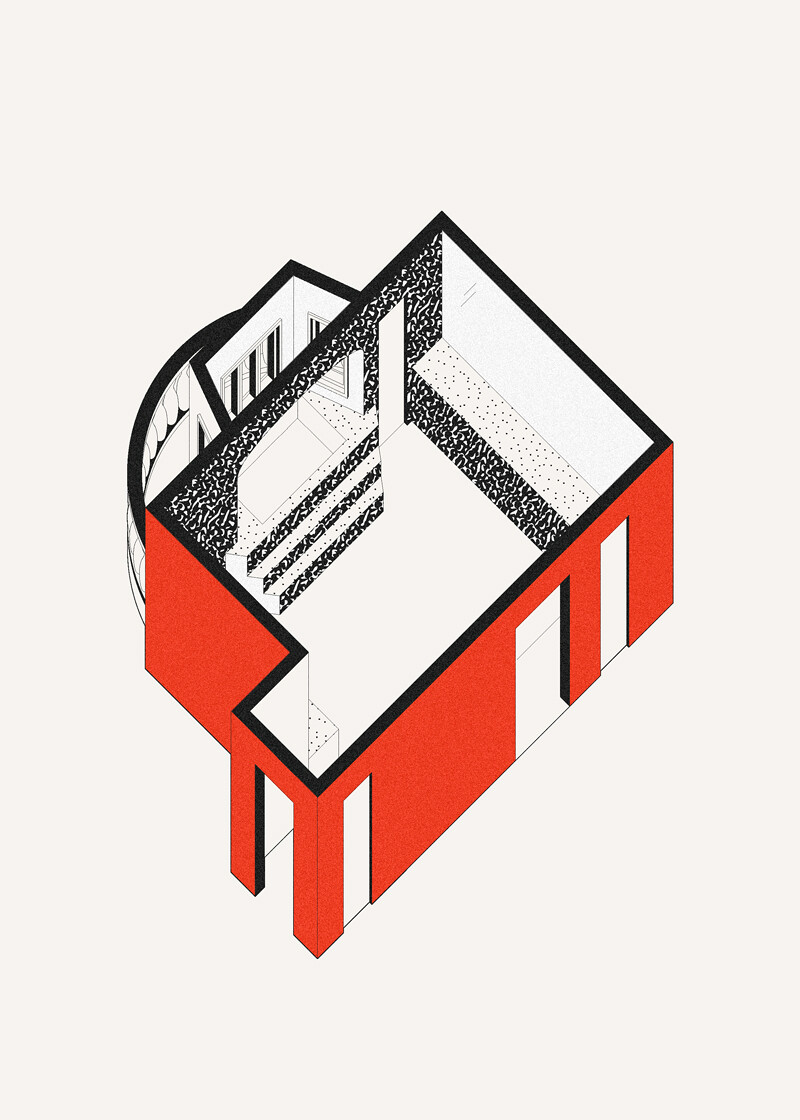

While the feed is a working representation of the whole, the post is a generative fragment; the unseen structure of the house. A group photo in a hot tub, a TikTok dance in front of the master bathroom mirror, a vlog in someone’s bedroom… Each crafted frame is an element in a larger plan. Via these virtual windows into the lives of the content creators, the house builds over time.7 This real-time construction of the content house requires deliberate maintenance, re-evaluations, and iterations; more group photos, more dances, and more vlogs. Yet, no matter how many posts are made, new gaps will emerge, and new assumptions will be fabricated. There is an endless construction and authentication of the architecture of this virtual elsewhere.

The content house is a double act: it may be an object in its occupancy, but through its representation, the house is always in the process of becoming something else. It is, but also not, at least not only. The nature of a post is that it can only produce a fragmented view—a buffer state—waiting for more posts to join them and aggregate towards the whole feed. The architecture of the house will never be complete. The medium does not allow for it. But also, it doesn’t matter. A content house is defined more by immaterial acts than material spaces. Only through documentation does a house become a content house. Otherwise, it’s just some random McMansion. The architecture of the content house is not just a product of collaborative labor, but a product of collaborative documentation.

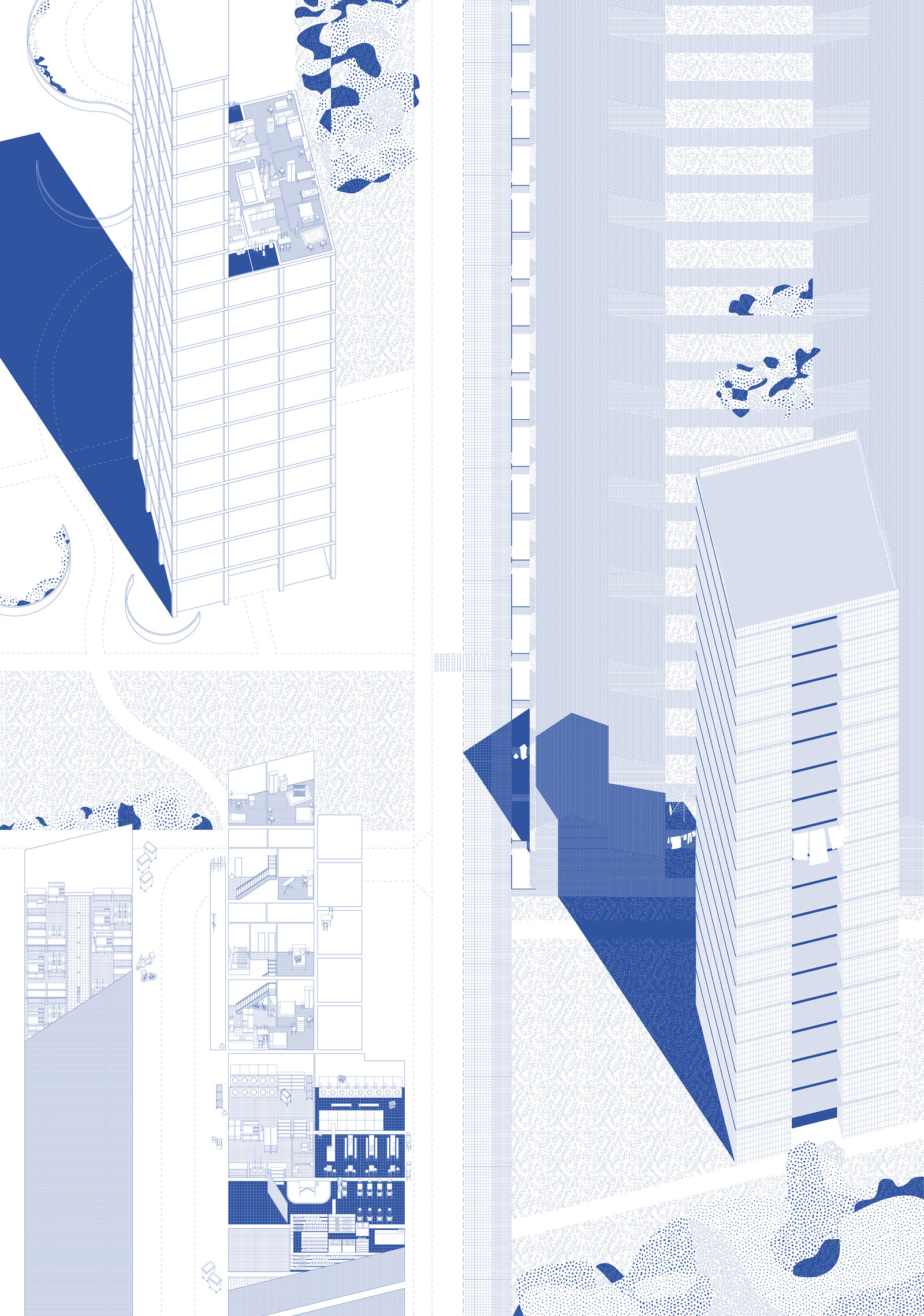

In the context of architectural labor, this critical approach to media isn’t entirely foreign. After all, architects don’t build buildings; they produce representations. An architects’ deliverables—precedents, readings, sketches, orthographies, details, models, etc.—are all performative artifacts that are not themselves architecture, but productive of it.8 They are instruments in the act of building. And much like a content house, a building takes a plethora of media to make it real. Content houses only become real through an aggregation of posts in the same way that buildings take a multitude of drawings, contracts, and specifications to be built. Even beyond primary construction, choreographies of occupation, maintenance, and alteration continue to influence the architecture in perpetuity. The single “money shot” rendering or photograph of an architectural project has always obscured the processes that gave it shape and rendered the labor behind it invisible. What, then, would it look like for architecture to embrace the paradigm of authentication and reality construction embodied and disseminated by content houses? And how would the conditions of our documentative labor change when they are made hyper-visible?

Social media’s functionality is dependent on intensifying existing social conditions. This means that anything that is fed through its framework will then become accelerated versions of itself. It’s not online life or real life, but hyper-real and real. This often makes critiques of the post or the feed’s inauthenticity mere simplifications of what a post actually does, and what a feed can be. While the feed may increase the feeling of falsehoods, it can also provide the means for a self-exposure that combats it. This condition is best illustrated by the contrasting ideas of performance versus parrhesia. Performance is a standard vanity post—intermittent hiking trips that bring punctuation in a life consumed with work, a breakage of digital silence to announce an unsurprising engagement, or a carefully staged image of mid-century whatevers—merely in search for validation and envy. The counter usage of the feed would be parrhesiatic. Parrhesia, in its most crude speculation, is content instrumentalized with the understanding that work is a practice, not a total sum of content. If performance is a codified effect of an adopted role, parrhesia is the unspecified risk from the commitment of practice.9 Practice, here, is done through the feed, but is not embodied by it. A post, then, is not a representation of something, like a building, but the material that we build with. And what exactly would we be building? In the aggregation of posts, the feed will propose answers.

“Shitposting” has been a common practice, primarily by anonymous meme accounts, to reject the pressure of passively conforming to the feed and adopting its problematics.10 Instead, by incessantly posting, they are engaging in real-time within a discursive process that disrupts its compulsions: a parrhesiatic practice of the feed in its full-blown unstable glory. The method of aggregation and built through a series of posts is ultimately the architecture of the feed. This feed, in the vein of Walter Benjamin’s Arcades, situates its audience in a dense, unknown territory, urging visitors to put in the work, to linger, to get their bearings.11 And if they do, walking through the proverbial front door, visitors reach a state of presentness, a space where it is possible to combat the endlessness of the feed.12

If any post is inherently fragmentary and incomplete, the labor of imagining, reframing, and recirculating content can be performed with greater intentionality and openness to iteration. Impossible to manufacture the whole, the part can become something highly specific. By accelerating the output speed of individual posts, the speed of the overall project—and our labor—can slow down. By working on parts, and not wholes, it’s easier to build positive feedback loops that affirm care within our process. The energy we put into our work needs to be less than what we receive for it to be sustainable—and survivable. When we post, we demystify the nature of work. With labor no longer unseen, and dialogues no longer inaccessible, value is brought to the roles we occupy. When we share our ideas, it informs the ability to reshare each other’s. It shouldn’t take scandal or glory to initiate mass dialogue. Isn’t it meant to be a social platform after all?

Conclusion

For the inhabitants of content houses—for modern citizens—everything must be posted.

Architectural work, and processes of work, is becoming increasingly molded through architects’ relationship with virtual social terrains. Popular media informs practice and practice informs popular media. In an era where media is inescapable, so is our role within it. This space of labor needs constant and active critical assessment before it cements itself as simple background noise, dulling our senses towards our already fraught nature of work. But it’s not necessary for us to forgo everything we know and retreat entirely into the content house. The best form of virtual utopias are ones that move towards better realities by being both practically attainable and offering combined expressions of human agency.13 It is only through engaging with these fast mediums, in tandem with the slow, can we begin to create alternative models of labor and actions of resistance. Fragmented documentation, horizontal frameworks, and self-determination: these are elements of the content house that architecture can start with.

So, to start: post everything.

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017), 1–23.

Taylor Lorenz, “Hype Hose and the Los Angeles TikTok Mansion Gold Rush,” The New York Times, 2020, ➝.

Dena Yago, “Content Industrial Complex,” e-flux (March 2018), ➝.

Rob Horning, “Presentness is disgrace,” Tiny Letter, September 25, 2020, ➝.

Ryan Scavnicky, “Mutant Authorship. Agency, Capitalism and Memes,” Archinect, September 11, 2018, ➝.

Willa Köerner, Software for Artists: Building Better Realities (Brooklyn, NY: Pioneer Works Press, 2020).

Anne Friedberg, The Virtual Window (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017).

Susan Satterfield, “Performances of Spatial Labor,” Journal of Architectural Education 73, no. 2 (2019): 230–239.

Rob Horning, “Games of Truth,” The New Inquiry (2013), ➝.

Yago, ➝.

David Wallace, “Walter Benjamin’s Unfinished Magnum Opus, Revisited Through Contemporary Art,” The New Yorker (2017), ➝.

Rob Horning, “Social Media Is Not Self-Expression,” The New Inquiry (2014), ➝.

John Danaher, Automation and Utopia: Human Flourishing in a World without Work (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

Workplace is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Canadian Centre for Architecture within the context of its year-long research project Catching Up With Life.