Nick Axel How do you understand the nature of public space in post-colonial cities?

Malique Mohamud There are always multiple interpretations of every public space. A good example of this in Rotterdam is Heemraadsplein, which is also called “Pracinha d’Quebrod,” or the “Square of the Poor.” The public square is surrounded by a lot of green, a lot of fancy houses. But it’s also in Rotterdam West, and in the neighborhood of Delfshaven, which is sometimes called the eleventh island of Cape Verde due to the large Cape Verdean community that lives there. Before mobile phones, Heemraadsplein was the first place people who just arrived in the Netherlands from Cape Verde would go. If they went there, other Cape Verdean migrants would approach them and help them find their way, to find a place to live, to find work, etc. That square, as well as other public spaces in the built environment, have multiple layers of meaning. This is because they have their intended functions, but then they also have informal functions that weren’t part of the designer’s initial intentions. Re-codifying and appropriating space happens a lot in migrant neighborhoods in Rotterdam. The communities that live there have had to find ways of building their lives. It wasn’t given to them, so they’ve had to appropriate squares, or nightshops, or other meeting spots throughout the city. These informal ways of using space are incredibly rich and dynamic. As a collective, we try to use the immaterial and material heritage of a post-colonial society to design spaces that actually serve the communities that we’re part of in a more intimate way.

Scenes at Bospolderplein. Concrete Blossom, Het Plein, Rotterdam, 2022.

Scenes at Bospolderplein. Concrete Blossom, Het Plein, Rotterdam, 2022.

Scenes at Bospolderplein. Concrete Blossom, Het Plein, Rotterdam, 2022.

The Het Plein duimdrop. Concrete Blossom, Het Plein, Rotterdam, 2022.

Scenes at Bospolderplein. Concrete Blossom, Het Plein, Rotterdam, 2022.

NA Can you give an example of how you’ve worked with public space in this type of way?

MM For the past few years, we’ve been working together with the community of Bospolderplein, another public square in Rotterdam West, on a project called Het Plein, or “the square.” When the neighborhood around Bospolderplein was originally built, the houses were generally too small for the families that lived in them, so everything spilled out onto the street and into the square. This means that, for generations, Bospolderplein has been the place where children who live around the square play, and also where their parents spend time with each other. There’s a basketball court, two football pitches, some steps with benches, and two playgrounds, one on each side of the square. It’s quite a huge place, or at least feels that way when you’re in it, and is almost entirely made of concrete. But today, the neighborhood is being redeveloped. Right around the corner from the square, new housing complexes are being built for more affluent people. But also, the globe is heating up, and concrete palaces such as Bospolderplein are heat magnets. This convergence of forces serves as an urgency to rethink and redesign Bospolderplein for the community.

NA How did this project come about?

MM Het Plein emerged from our partnership with Het Nieuwe Instituut, which is an institution with a significant international profile but is largely alienated from the city’s migrant communities. They want to relate to the city as it is, but need guidance. One of the things we tried to do with Het Plein is think of ways that public institutions can not only talk about things, but actually facilitate communities that are addressing things in the here and now. We are also constantly asking ourselves what tools we need to not just appropriate the built environment in an informal way, but to reimagine the public domain? To do this we draw from and try to be exponents of hip-hop culture, which as the preeminent force of cultural production in the Netherlands builds upon what happens every day in these types of spaces. And then there is the actual square itself, and its community. The people who live there have tons of knowledge about what that square means and how it is used. What we have done is bring together people from the community with an architect of Cape Verdean roots, Zico Lopes from the studio Spatial Codes, to actually reimagine the square.

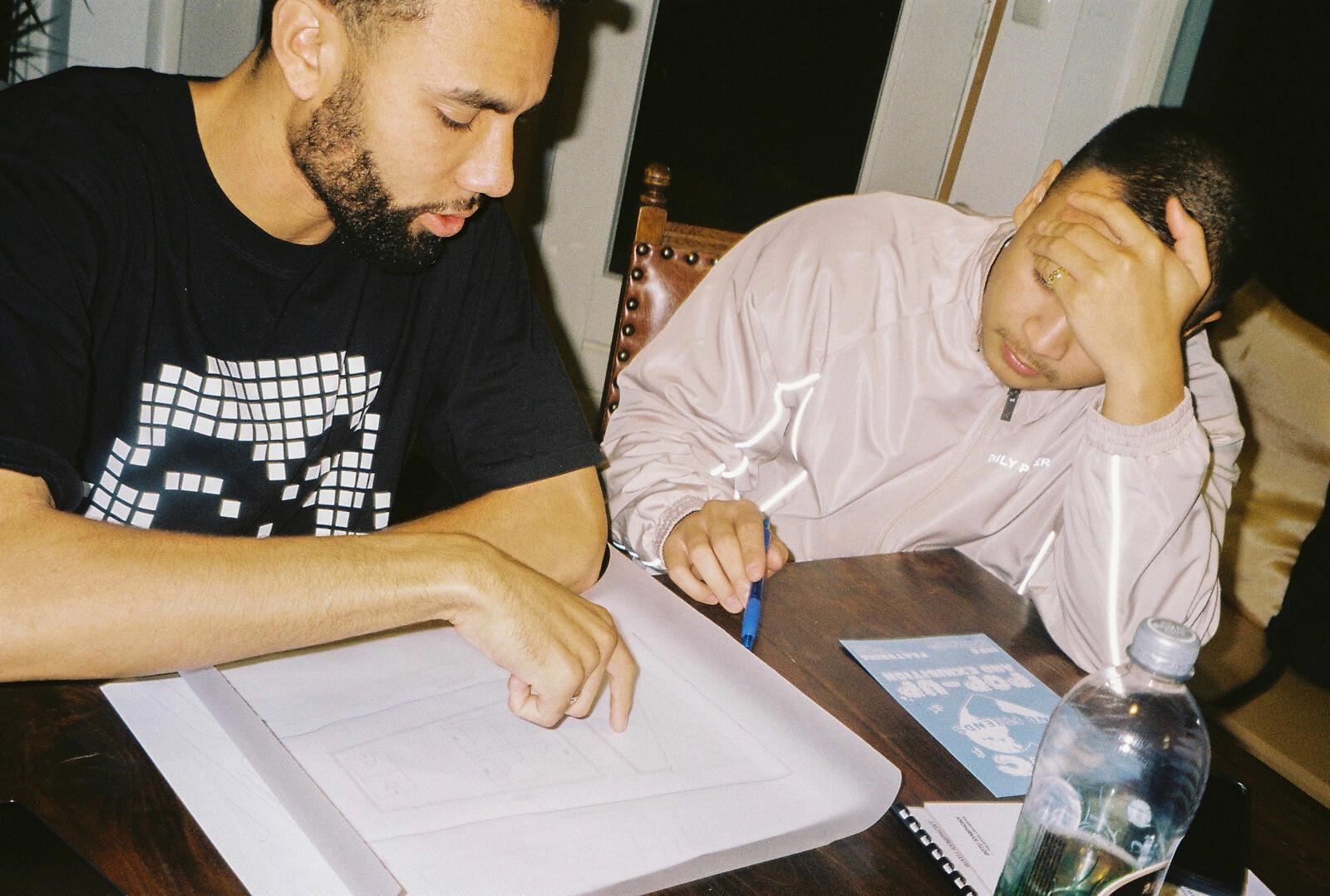

Yout does research by talking to each other about their lived experiences. Concrete Blossom, Het Plein, Rotterdam, 2022. Photo by Sethi Djegane Gueye.

Yout visit the archive at Nieuwe Instituut. The archive of previous designs of squares is examined. In the background archived models of Markthal by MVRDV. Concrete Blossom, Het Plein, Rotterdam, 2022. Photo by Sethi Djegane Gueye.

Yout does research by talking to each other about their lived experiences. Concrete Blossom, Het Plein, Rotterdam, 2022. Photo by Sethi Djegane Gueye.

NA If you’re bringing together governmental and cultural institutions with local communities, all these groups of people speak very different languages. How do you get these different parties to not just talk to each other, but actually understand what is being said and work together?

MM First and foremost, you need to have the audacity to actually believe that we are capable of challenging, if not redefining what the public domain is. There’s this lack of capacity in public institutions to connect with a community’s urgencies and respond to the actual experience of the people who live there. What we try to do is take the desire that public institutions have to be relevant and align it with actual things that are happening on the ground. But this comes with a lot of headache, a lot of code switching, a lot of mediation, a lot of translation. Since I’m not a trained designer, I had to learn a vocabulary. There are certain codes and ways of speaking that run deep in the design professions, and without being able to perform in that way, you can’t be taken seriously. Plus, people in power tend to reduce hip-hop to folk and just brush it off as street culture. They can’t understand the capacity or the meaning of the culture that we live day-to-day. But by learning their language, and by code switching, or intentionally not code switching, we also produce new knowledge. Because that’s what the neighborhood does. That’s what happens in a place like Bodpolderplein. Straattaal, slang is produced.

NA A lot of this culture you’re speaking about is ephemeral. This makes me see Het Plein almost as an archive, or even a memorial to all of the memories, the knowledge, and the experiences that have come from Bospolderplein.

MM Definitely. On one hand archiving it and memorializing it, and on the other using it to design the future of the square. For instance, the youth that we are working with weren’t even conscious of the fact that they could have an opinion about, let alone imagine what the square would look like. A lot of people don’t feel a sense of ownership over those processes. It’s only something that happens to them. But these people use the space every day. They know what is being used and what isn’t. They also know how things change, or what it takes to change them. Giving the community the tools to actually engage with the neighborhood—giving them the belief that their knowledge, that what they see and experience can have an impact on their daily life—is empowering. A few people actually ran in local elections after participating in this project, because they realized they could have a say.

NA What are some examples of these insights from community members, and how have they translated into design proposals?

MM One member of the community, Brahim, noticed that the shipping container in the square that holds play equipment—what’s called a duimdrop—was closed over time, as a result of budget cuts. But this urban facility is incredibly important. It gives children access to toys that they might not have individually in their own homes. It also teaches them how to share, how to cherish moments of play, how to help and support other people. When reflecting on this in the process of reimagining the square, people from the community said the duimdrop shouldn’t just stay and be reopened; we need a duimdrop XXL. Another member of the community, Monday, spoke with his mother, who said she doesn’t use the square anymore because her children are old enough to move around independently through society. He asked her what could be done to the square to make it still useful to her. Her response was so simple: a place to sit in the shade. This insight comes from an intimate understanding of how black and other diasporic communities from the global south engage with the outdoors. In a society that is becoming more and more complex, design practices are needed that have a deep understanding of that knowledge and an ability to interpret it. Adding all these humble insights together creates an incredibly rich vision for what that square could be.

NA As you’ve been collecting these different ideas of what Het Plein could become, how have you turned these ideas, insights, and knowledge into a design project that speaks the language of the city government and its politicians?

MM Before I answer that, I need to make a distinction between a few different processes: the process that brought the various people together, and the translation of the ideas generated by them into a design. As Concrete Blossom, we designed the former process as a collective, and Zico Lopes spearheaded the design process, the translation of the data and the ideas that the community researchers brought to the table. The humility with which Zico translated their ideas was inspiring. One of the things I learned in our collaboration with Het Nieuwe Instituut is that a lot of architects have difficulty with context. They want to design, to create, to determine what is suitable for a place. The approach that Zico had was in stark contrast to approaches that I saw from other architects. He was actually synthesizing and translating the community’s ideas. That’s really difficult. Sometimes the most suitable intervention is to do something really simple, like turn one of the football pitches into an astroturf Cruyff Court. It takes courage to not do more.

Collage of proposed Het Plein cruiffcourt. Render by Zico Lopes.

Collage of proposed Het Plein fitfree Moestuinpaviljoen. Render by Zico Lopes.

Collage of proposed Het Plein callisthenics facility. Render by Zico Lopes.

Collage of proposed Het Plein pop-up market. Render by Zico Lopes.

Overview of Het Plein proposal. Render by Zico Lopes.

Collage of proposed Het Plein cruiffcourt. Render by Zico Lopes.

NA The act of synthesizing all different perspectives and desires is at the core of architecture. But at the same time, I would argue that architects almost inherently distrust clients, users, or basically anyone who is not an architect. There’s always an idea within architecture, at least in its more traditional forms, that people don’t actually know what they want, that architects know how space works better. While sometimes this is true—designing space is incredibly complex—intervening into a place where people have lived their entire lives requires incredible sensitivity. What was the process like working with the community?

MM The first thing we had to do was try to align the goals of Het Nieuwe Instituut with the aspirations of the community and the architect. To negotiate agency and autonomy in this complex space, we used this model called the tussenruimte, or the “in-between.” We invite various stakeholders to talk and bring their aspirations, their desires, and their agendas, and then visualize the spaces in-between. There’s all this talk about the need to “build bridges,” but bridges imply that some people need to cross from one position to another. What if there’s an in-between space is a destination in and of itself, a temporary destination where people can align goals and think together? Beyond this, we have a few lenses, or terms that can be used to change the debate. One of these is “the sauce,” or fringe capital, which is cultural capital produced at the fringe of society. There are many definitions of “cool,” but one put forth by African American historian William Cobb defined it as the state of “negro zen.” Cobb argued that if the world is built to keep black folk perpetually off balance, then cool is the ultimate retaliation. So if cool is a state of being, and if hustle is the praxis, then it culminates in sauce, which is a form of capital, a form of embodied knowledge that is produced on a personal level. But in a neighborhood such as Delfshaven, there’s a high concentration of sauce, which gets extracted by public and private entities that refine, repackage, and sell it back to us. “Sauce,” or fringe capital, is one lens. “Buurt,” or “neighborhood,” is another, which is like a collective consciousness of people who grew up in certain places like Bospolderplein or Delfshaven. There’s also “tnaoui triangle,” which loosely translates from Moroccan to “fuckery,” and is a model we developed that illustrates how frames are produced through discourse. It’s interesting to see what happens when we introduce this vocabulary within institutional spaces. Often there’s understanding from some people, but not others. This toolkit therefore not only empowers certain people, it also invites others to do the labor of understanding different languages and different ways of being.

NA How important is it to you that the plan Zico designed for Het Plein gets realized?

MM We’ve said from the onset of the project that our goal was not necessarily to redevelop the square. It would be great if that’s possible. But more important than that is to invigorate various communities that engage with public issues and bring forth different strategies to reclaim governance. Het Plein can hopefully inspire people to dare to think what more we could do.

Where is Here? is a collaboration between Het Nieuwe Instituut and e-flux Architecture following Who is We?, the Dutch pavilion at 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale.