The Deceptive Tranquility of Settler Colonial Landscapes

One of the ways in which settler colonialism operates is by concealing its logics in seemingly objective data about contaminated land. There are two distinct but linked logics of representation of the landscape at play here. First is the portrayal of landscapes as tranquil, neutral, and quiet. This concealment can take place at the scale of bodily experience. Walking through sites where pollution dwells quietly below the surface, there may be no markers, or at least no markers that can appropriately convey the scale, extent, and drama of the contamination. Second is the use of data and numbers to obfuscate the truths represented in that very data (an obfuscation that typically excludes any understandable visualization of that data). These representations use abstract terms and abbreviations. Many people struggle to understand what things like PCBs or PPM mean or how they relate to phenomena witnessed in everyday life. Exhaustion sets in as people struggle to make any sense of objective datasets. These representations, then, might provoke despondency or a sense of helplessness and are not likely to lead to action.

These difficulties are compounded by the fact that landscapes play a role in deception. They can look so normal, so innocent, and even beautiful, while also containing toxins. Landscapes can help us to believe that all is well and good and that we don’t really need to organize to force the government or corporations to clean the toxins from the soil. In the case of Ringwood, New Jersey, it’s hard to even fathom the depths of the problem because so much lies deep below the surface. I first visited Ringwood in February of 2018 with Chief Mann of the Ramapough Lunaape Turtle Clan and a group of students enrolled in my landscape design studio at Rutgers University. Although we knew about the contaminants and toxins that lingered deep in the soil, everything looked normal; we saw a beautiful wooded landscape, slightly subdued by the rainy weather, interesting herbaceous foliage, and a number of cute, tiny frogs.

But we knew that we were on a highly contaminated Superfund site. We had studied EPA reports that detailed paint sludge removal locations and outlined facts and figures about the PCBs, DEHP, and VOCs trapped in the sludge in an unknown pattern in the woods, following Ford Motor Company contractors’ clandestine “midnight landfill” deposits in the 1960s and 1970s. We knew that barrels of toxic material had been dumped down the shaft of the old iron mine that ran 1,800 feet below ground. Moving deeper into the site, we encountered running streams and ponds where the surface of the water at times exhibited a perverse, unnatural sheen—a kaleidoscope of refracted colors on an oily substrate.

Located just a few miles upstream from the Wanaque Reservoir, the Ringwood Mines/Landfill Superfund site is also where, just a few decades ago, the Ramapough Lunaape Turtle Clan used to swim, ice skate, and drink from the clear running water. It is where their ancestors called home for centuries, and where some members of this Native American community still live today.

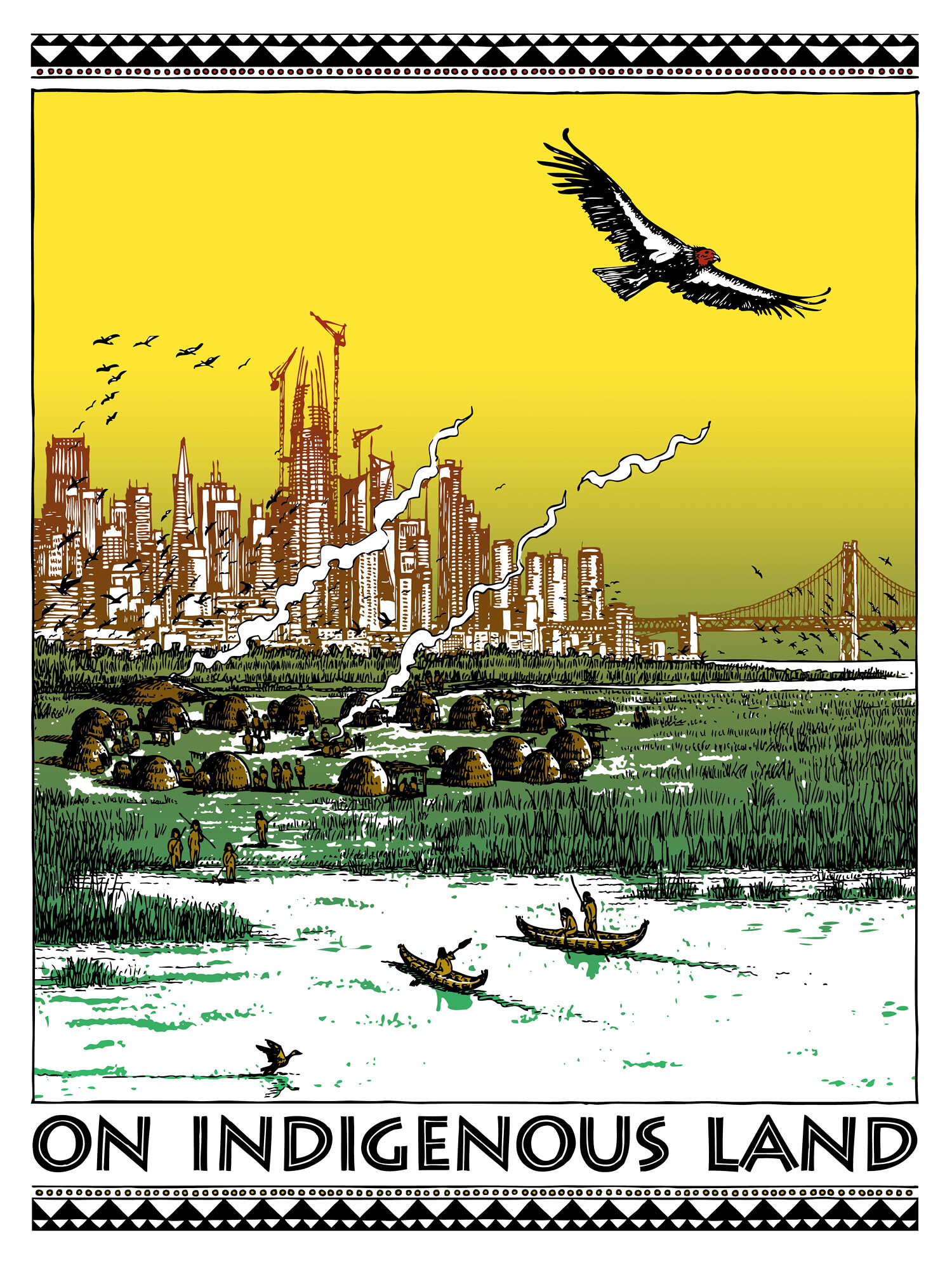

Considering the presence of Native Americans on this site, it is necessary to discuss a third logic of settler colonialism’s representational strategies, one that has been at play since the early days of the nation and that facilitated its expansion by means of land appropriation. This is the depiction of Native Americans as belonging to a distant past rather than a lived present. As Thomas King has explained, North America has often represented Native peoples as “doomed, dying, or dead.”1 These romantic representations are much more palatable than messy realities. “Dead Indians are dignified, noble, silent, suitably garbed. And dead. Live Indians are invisible, unruly, disappointing. And breathing. One is a romantic reminder of a heroic but fictional past. The other is simply an unpleasant, contemporary surprise.”2

In addition to the “Dead” and “Live” categories, King adds a third— the “Legal” Indian. These are individuals who are officially registered in tribal roles, have governmental recognition, and have access to rights accorded to sovereign tribal nations. He notes that, due to the bureaucratic difficulties and official mid-twentieth-century policies of Termination (and laws such as House Concurrent Resolution 108, which called for the immediate termination of several tribes, ending their access to federal services and protection and their reservations) only about 40% of people with Indigenous heritage living within the United States and Canada have been able to be recognized as “legal.” “North America hates the Legal Indian. Savagely. The Legal Indian was one of those errors in judgment that North America made and has been trying to correct for the last 150 years. The Legal Indian is a by-product of the treaties that both countries signed with Native nations… they’re called treaty rights… Legal Indians are the only Indians who are eligible to receive them.”3 In addition to enabling the avoidance of decreed responsibilities to Native communities, such representations also contribute to “a pervasive myth in North America [that] supposes that Native people and Native culture are trapped in a state of stasis.”4

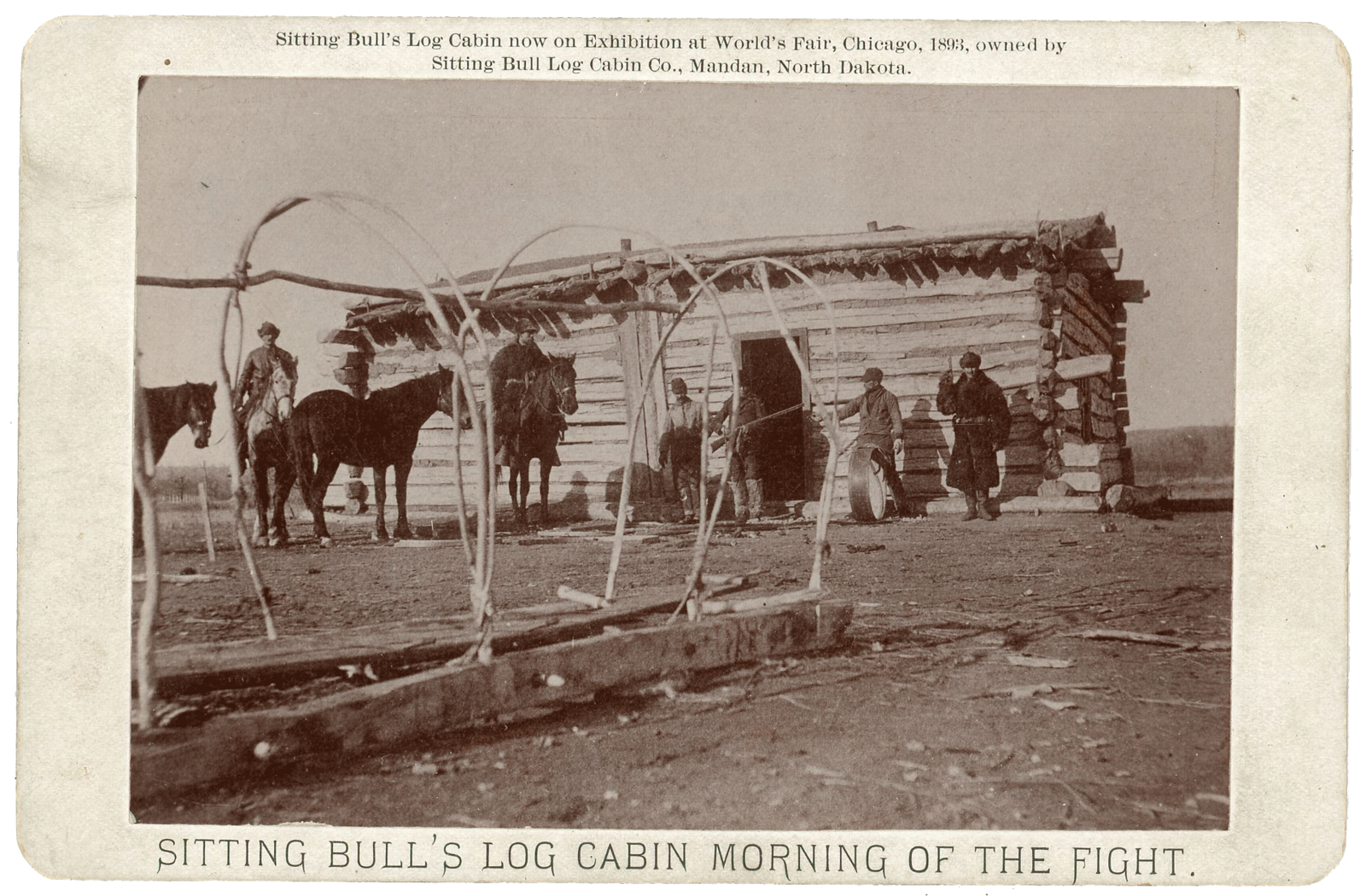

The 2003 Indian Memorial at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, the site of “Custer’s last stand,” exemplifies this representational entrapment. The Spirit Warrior’s sculpture is a kitschy pastiche of typical depictions of Native Americans and speaks to the role they occupy in the American imagination. Tribal leaders have criticized the sculpture for its inauthenticity and subsumption of different tribes into one category. Dennis King, then vice chairman of the Oglala tribe, complained that “They glamorized the whole thing … and put up a monument that isn’t us… If you didn’t know about our culture, you’d think this memorial reflects us spiritually… They just Hollywood-ized it.”5 These types of representations help to justify the political agendas of settler colonialism and take urgency away from indigenous political demands. While park rangers stated that the memorial’s creation has “really taken the pressure off” of them to tell that side of the story, Erica Doss points out that “there is no hint, save the occasional button left at the Spirit Warriors sculpture reading, ‘The Black Hills are NOT FOR SALE,’ that land rights and civil rights remain key political priorities for contemporary Native Americans.”6

The Violence of Settler Colonial Representations

Settler colonialism’s representation of contaminated landscapes invite people to ignore the presence of toxins and, in a way, legitimize these toxins being left in place. Thus, even as data documents the presence of noxious chemicals, the agencies and corporations that produce this data can continue to hide behind the difficulty in interpreting it, enabling the continued exploitation of land and resources.7 Ideologies can therefore be hidden in plain sight. As Dianne Harris points out, “landscapes are particularly well suited to the masking of such constructions because they appeared to be completely natural, God-given, and therefore neutral and because they serve as unnoticed background to our everyday lives.”8

Racism also plays a role here as degraded landscape conditions are associated with particular communities and thereby linked to personal responsibility and the poor choices of residents. Barbara Williams, a reporter for The Record, was on the Toxic Legacy investigative journalism team that helped to bring to light the presence of contaminated material in Ringwood after the EPA supposedly completed remediation in 1994.9 Williams describes the reaction to the Ramapough’s experience living on contaminated land:

I’ve been told they deserve everything they get. I can’t tell you how many emails I’ve gotten, or phone calls, from people in the community saying when are you going to tell the real story about the people up there, that they’ve created their own lives, they’ve created their own mess…10

Data presented in publicly available reports and at community meetings functions to aid in the absolution of responsibility to land and to community. The Akwesasne Mohawk community, located near two New York state-mandated Superfund sites, offers one such example. One site was polluted by General Motors Corporation. After the 2008 financial crisis, the corporation received $49.5 billion in bailout money, filed for bankruptcy, and then reemerged as General Motors LLC, a new company that was freed from any responsibility to remediate contaminated sites in thirteen states.11 In the case of Ringwood, the Mann v. Ford court case filed by residents of Ringwood against Ford Motor Company was derailed by Ford’s reporting of financial woes, leading to a paltry monetary settlement for the community. The cleanup of the Superfund site is ongoing and Ford continues to propose a shallow cleanup with the much less expensive option of capping the site, rather than fully excavating and removing toxic material. Adding insult to injury, the town continues to push for the construction of a recycling center on the O’Connor Disposal Area, a dumping site that still requires remediation, after it is capped.12 The vibration of heavy trucks on the cap has the potential to cause more damage, and certainly will bring additional noise and traffic into the heart of the Ramapough community.

Underground Architecture of Toxicity and Damage

Intertwined with the early history of the United States, environmental violence led to the despoilment of the environments that Indigenous peoples relied on for survival. One example was the extermination of tens of millions of bison from 1865 to 1883, eliminating a primary food source of the Plains nations and thereby stamping out their possibility for resistance. This violence is not a thing of the past but continues today as food sources are compromised due to environmental contamination. As of 2017, Native American communities lived near approximately 600 of the 1,338 highly contaminated Superfund sites listed across the country. This has led to the disruption of traditional economies of fishing, hunting, foraging, and gardening, and curtailed access to sources of healthy food.13 As Stuart Harris and Barbara Harper point out, “because tribal culture and relation are essentially synonymous with and inseparable from the land, the quality of the sociocultural and ecocultural landscapes is as important as the quality of individual natural resources or ecosystem integrity”14 Environmental disruptions affect Native American communities in profound ways as traditional relationships with the land are compromised along with the ability to eat healthy food through a subsistence lifestyle. Traci Voyles points to the entanglement between settler colonialism and the environment for Native Americans, whereby “even the phrase ‘environmental racism’ can seem to lose the whole meaning in a tribal context, simply because ‘racism’ has always meant environmental violence for native peoples.”15

Despite having drastic impact on the lived experiences, foodways, and health of Native communities, much of this damage remains invisible to the public eye, seen only as signs in the landscape that state “Do Not Enter,” or “Catch and Release Fishing Only.” We have no way to see what lies behind these signs or beneath the surface. Located near Ringwood, the Ford Motor Company production plant in Mahwah generated hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of waste and millions of gallons of paint sludge while it was in operation from 1955–1980. For each car made, five gallons of paint waste was produced, equating to 6,000 gallons of sludge a day. Much of this waste was disposed of in the Mine Area of Ringwood in the 1960s and 1970s. Residents recall the sound of large trucks moving down Peters Mine Road in the middle of the night, when barrels of sludge and other waste were pushed into the shaft of Peters Mine, tumbling down the seventeen underground levels on a 2,400 foot decline. Paint sludge contains a number of carcinogens including lead, arsenic, antimony, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), and acetone.

Peters Mine lies just a few miles from the Wanaque Reservoir, which provides drinking water for over two million New Jersey residents. Concerns have been raised by several parties that contaminants might migrate into the reservoir. If this does occur, it would impact nearly every resident of northeast New Jersey, since some portion of their water supply comes from the Wanaque Reservoir or the Ramapo River.16 While there may not be evidence of contamination of the Wanaque Reservoir today, concerns remain about contamination in the near or distant future because there is limited knowledge about the underground movement of water in the mines or the nature and extent of percolation through fissures and cracks in the bedrock.17 Water protectors take multiple forms and shapes, and the Ramapough have been standing for decades to protect the watershed that connects millions of people.

Non-hegemonic Visualizations of Damaged Landscapes

So much damage remains hidden underground, appearing only in the form of signs, minor moments in our landscape encounters, or obtuse data. In order to bring this damage to light, we need stories told by non-hegemonic voices to explode the illusion of tranquility and bring what has been buried back up to the surface. This damage cannot be recovered through physical or material excavation; narrative and visualization is required. Voices can be raised up as a form of protection and care.

While scientific studies provide knowledge, they can also strip away significance. Using numbers, figures, and statistics to describe environmental losses, this abstract and academic language is sterile; it misses something vital and important in terms of human experience. There is more to Superfund sites than contaminants and remediation strategies; these sites are part of the web of environmental relationships that define the landscapes in which we all make our home.

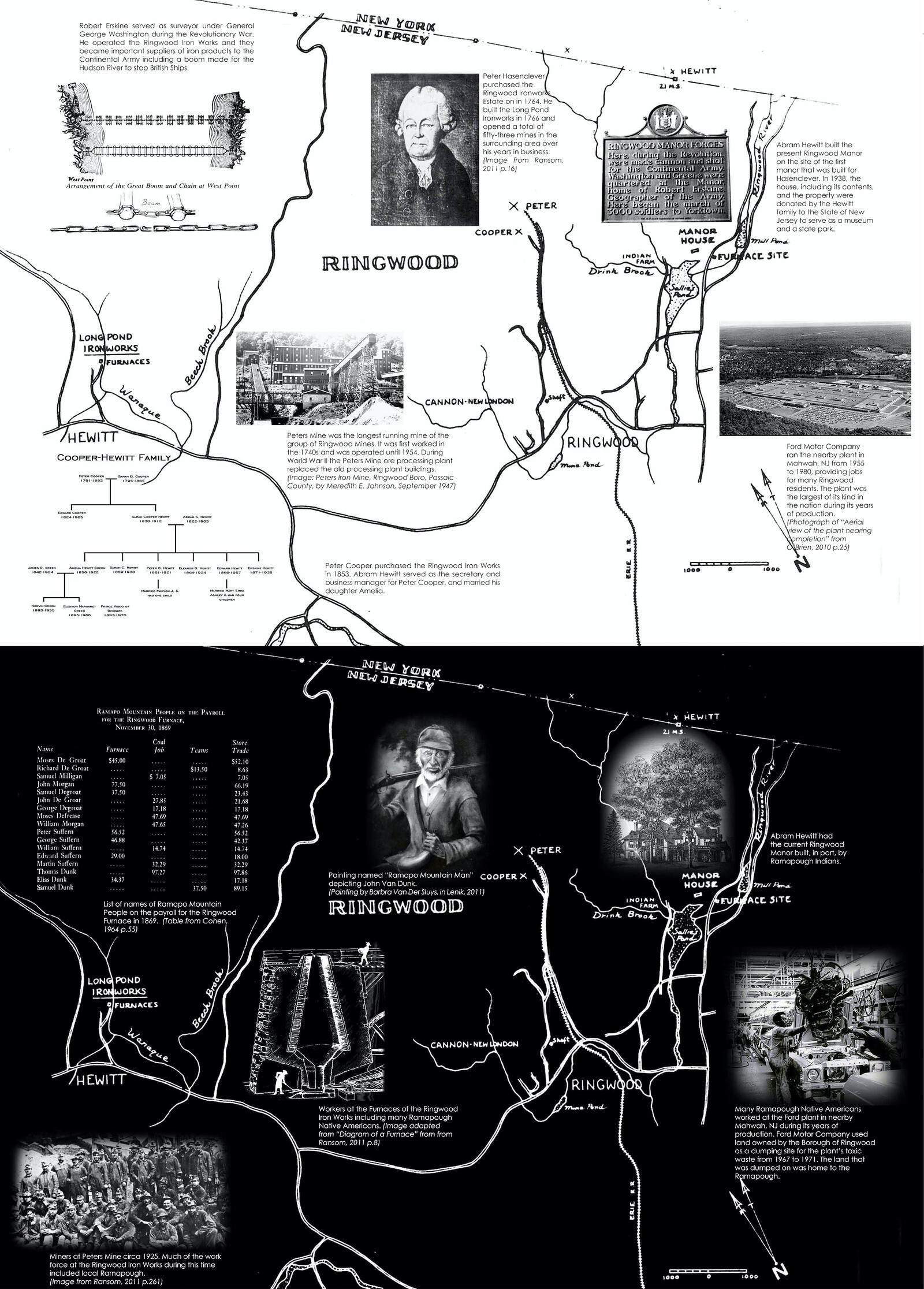

The project Our Land, Our Stories, for instance, creates clear depictions of the land and makes complex scientific data accessible. Funded by the New Jersey Council for the Humanities and created in collaboration with the Turtle Clan, it presents detailed environmental data from EPA reports and scientific studies side by side with narratives of human experience, thus representing the connections between the environmental, cultural, and political histories of what some know only as the Ringwood Mines/Landfill Superfund Site.18

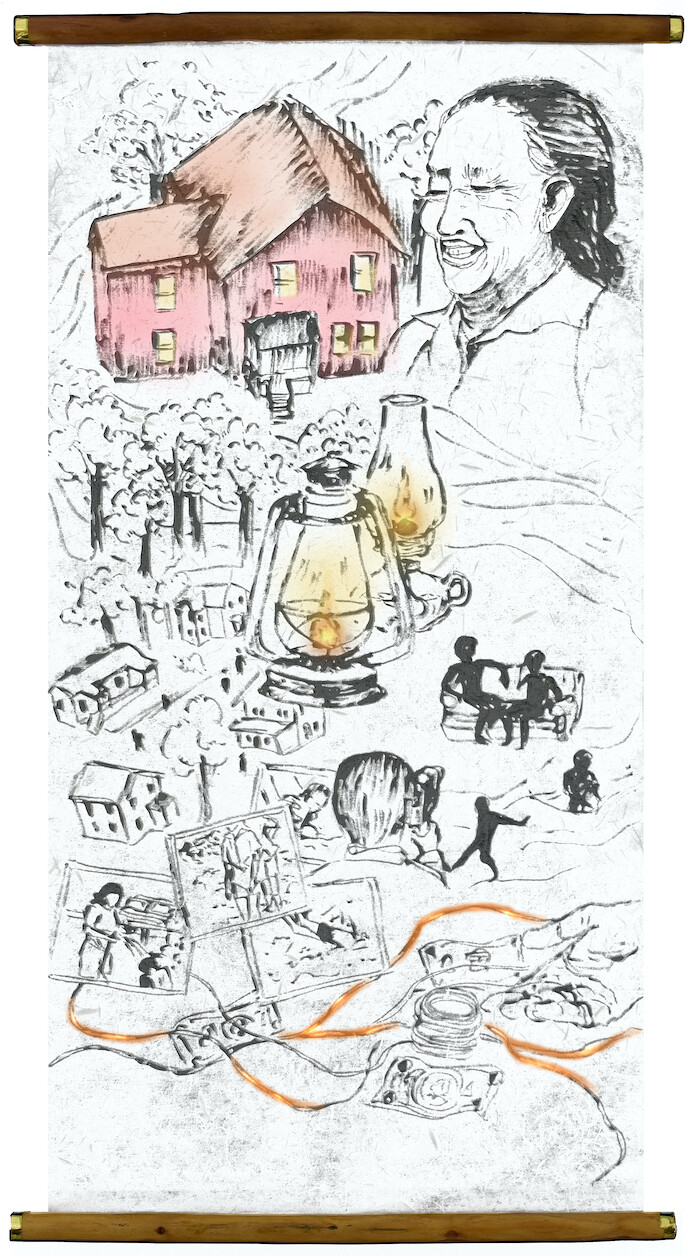

Alongside an exhibition, a book was made that consists of thoroughly researched information about the site and its residents, visualizations of complex environmental data from EPA reports, imaginative renderings of traditional Lenape stories, personal testimonies from the Ramapough, and essays from project partners. It clarifies contested narratives through clear graphic representations that illustrate the connections between different sets of scientific data, environmental remediation reports, records of the site’s industrial history, and personal narratives of the cultural and spiritual traditions of the Ramapough community.

Vivian Milligan is a community elder. She lives in one of the old mining houses, right next to Peters Mine, where a lot of the sludge was dumped. Depicted here are some of the things she values most about her community—living in a place that feels like a circle, where everyone is family. Drawing by Lydia Zoe, Research Assistant, Department of Landscape Architecture, Rutgers University.

Conclusion

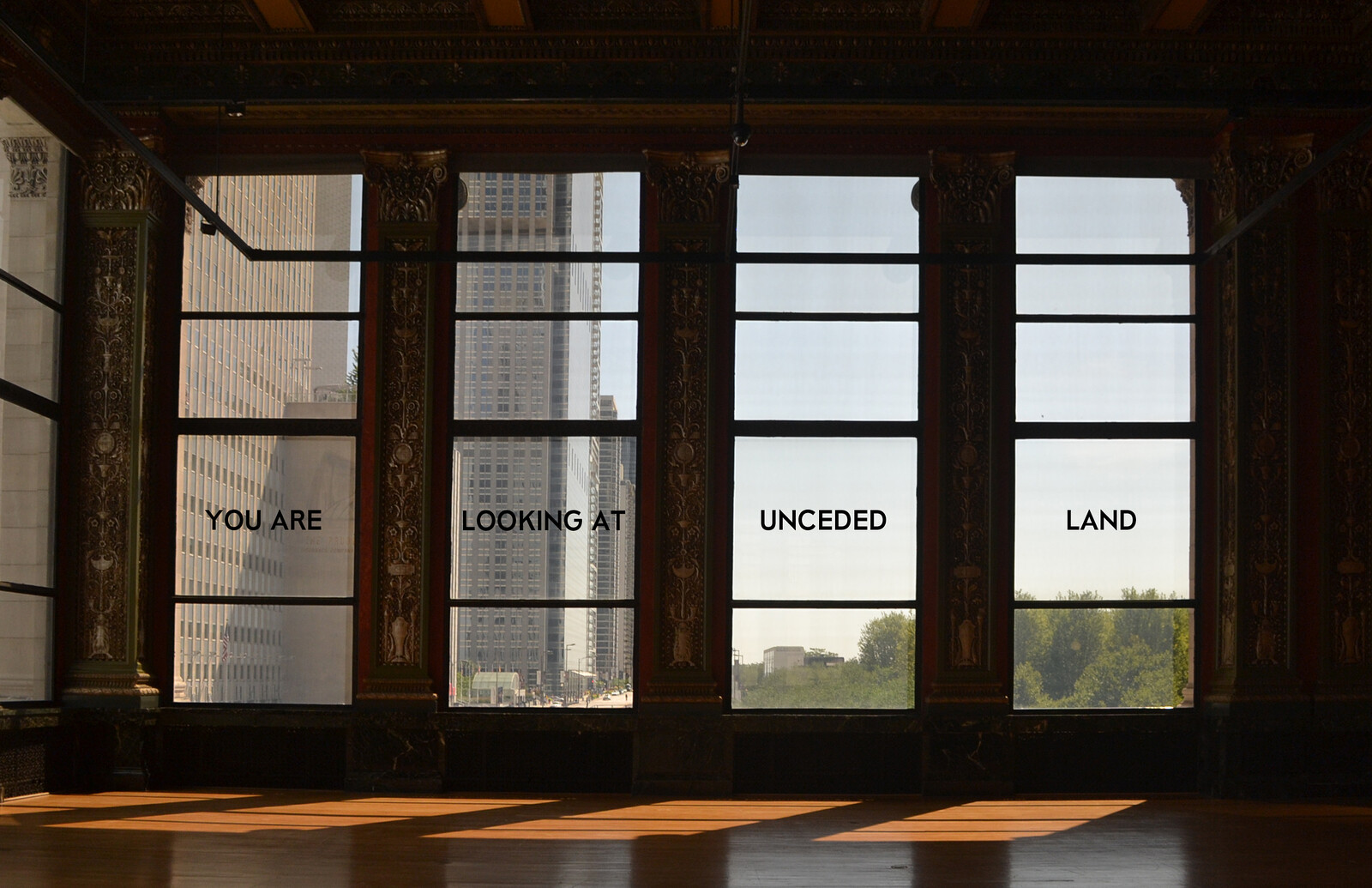

Much has been written about how settler colonialism operates to gain access to territory, and to set up a new society (ours) on this land. Settler colonialism works hard to hide this acquisition from us, cloaking the violence of its actions in objectivity and tranquility. There is no place for culpability in the logics of its representations of the land. In the words of Patrick Wolfe, “Settler colonialism destroys to replace.”19 This destruction is also executed through the creation of new representations that obstruct and obscure certain truths. It is difficult to see and hear these realities, these stories, these experiences. We must work hard to do this, to make space for narratives and visualizations that expose and fill in these false absences. When examining the contaminated landscapes of settler colonialism, we must do more than simply look at facts to acquire knowledge. We need to develop the skills to see what hides beneath the logics of its representations.

Thomas King, The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America (Canada: Anchor Canada, 2012), 30.

Ibid., 66.

Ibid., 69.

Ibid., 78.

Erica Doss, Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 363.

Ibid.

Anita Bakshi “Responding to Emotional Aspects of Environmental Loss: Implications for Landscape Architecture Theory and Practice,” Landscape Research Record 7 (2018): 49–59.

Diane Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 31.

The Record Staff, Toxic Legacy: Making a Wasteland (Bergen County: The Record, 2011).

Maro Chermayeff and Micah Fink, Mann v. Ford (New York: HBO Documentary Films, 2010), DVD.

Elizabeth Hoover, The River is in Us: Fighting Toxics in a Mohawk Community (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 116.

“Settlement will provide nearly $21 Million for Cleanup at the Ringwood Mines/Landfill Superfund Site in New Jersey,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, May 5, 2019, ➝.

Hoover, The River is in Us.

Stuart G. Harris and Barbara L. Harper, “A Native American Exposure Scenario,” Risk Analysis 17, no. 6 (1997): 782–95, 793.

Traci Byrnne Voyles, Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 2015), 23.

All the state’s major water suppliers draw from these sources. David M. Zimmer, “Ringwood aims to make Wanaque Reservoir scenery, not supply,” Northjersey.com, October 20, 2017, ➝.

Chuck Stead, “Ramapough/Ford: The Impact and Survival of an Indigenous Community in the Shadow of Ford Motor Company’s Toxic Legacy” (PhD diss., Antioch University, 2015), 31.

Our Land, Our Stories: Excavating Subterranean Histories of Ringwood Mines and the Ramapough Lunaape Nation, ed. Anita Bakshi (North Brunswick: New Jersey Council for the Humanities, 2019).

Patrick Wolfe, “Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409.

The Settler Colonial Present is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Settler Colonial City Project, with the support of the Department of the History of Art and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan.