Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

March 16, 2024 – Review

“El fin de lo maravilloso. Cyberpop en México”

Gaby Cepeda

In her curatorial text for this group exhibition of Mexican artists mostly born in the nineties, Karol Woller Reyes defines a “generational imagination.” It belongs to artists who have “naturally incorporated some creative strategies” such as digital montage and circuit bending into the production of paintings and sculptures that also abound with references to pop-cultural figures from Pokémon to Pepe the Frog. The implication is that the art of today is shaped by the technologies and media environment of its makers’ adolescence. Shared access to cable TV and computers during childhood does not, however, a generation make.

One of the narrow aisles that encircles the warehouse-like main gallery at Museo El Chopo housed the first, smaller part of “El Fin de lo Maravilloso.” Tucked to the side of the glass-walled gift shop were pieces by YOPE Projects collective crowded into a scaffold structure resembling an open-air market; a very early José Eduardo Barajas painting of cloudy emoji-like figures (Cirrus, Socrates, particle, decimal, hurricane, dolphin, tulip, Monica, 2018) in a freestanding wooden frame; and ¿Estamos, Kimosabe? (2020) a much-exhibited soft sculpture of a Mexican Bugs Bunny by Paloma Contreras Lomas—which judging by the dirt on its paws, has seen better days. …

February 15, 2024 – Review

Pedro Lasch’s “Entre líneas / Between the Lines”

Mariana Fernández

Pedro Lasch’s mid-career survey at Laboratorio Arte Alameda begins with a painting—the ultra-deadpan McSickle, grande no. 1 (2003)—depicting a yellow hammer and sickle fusing with the “M” of McDonald’s on a red background. These two colors also happen to make up the Chinese flag. The painting exemplifies the multiple layers of Lasch’s practice: the artist is best known not so much for making things as for creating opportunities for social encounter and collaboration through his roles as an activist, educator (he teaches at Duke and is the director of its FHI Social Practice Lab), and cultural organizer (with the collective 16 Beaver). Yet the thematic survey “Pedro Lasch: Entre líneas / Between the Lines” manages to avoid the document-heavy trappings into which displays of socially engaged art sometimes fall because of how well Lasch’s social practice translates into objecthood. The survey shows that whether in the form of painting, installation, props, performance scores, or game instructions, Lasch has long been thinking about the tensions between colonialism and cultural exchange, and using art as an entry point into public engagement with a decolonial agenda.

These themes are on full display in the mural painted on the back wall of the main …

April 14, 2023 – Review

Bayo Alvaro’s “¡Suéltame!”

Gaby Cepeda

Bayo Alvaro’s recent sculptures—evocative of strange, alien flora—recall Karen Barad’s descriptions of a “queer performativity” of nature. In this conception of the natural world, nothing is ever exclusively male or female, animate and inanimate; nor is it simply good or evil. Rather, there is endless potential for change and intra-action. The pieces in Alvaro’s third solo show in Mexico City and his first with Deli—a recently opened branch of the New York gallery—appear laced together in symbiosis, reflecting the ways in which living beings continuously tend towards and transform one another.

The young Mexican artist has previously worked across photography, collage, and installation. Here, the focus is on sculpture. The fifteen pieces lushly spread across Deli’s spacious, four-room gallery showcase Alvaro’s approach to sculpting forms that defy easy categorization, ambiguously poised between plants and animals, living creatures and inanimate objects. Alvaro’s objects are particularly lucid examples of a common trend in contemporary sculpture: his seductive treatment of materials sets him apart from more discursive, didactic attempts.

Each room feels thoroughly articulated. Pieces are placed in proximity, as if engaged in intricate dialogue, while smaller works are arranged as if to form an intimate ecosystem. Such is the case in the …

March 17, 2022 – Review

Leonor Antunes’s “the homemaker and her domain, part iii”

Jayne Wilkinson

Leonor Antunes has described her latest exhibition as a library, or an archive. The vast range of materials—jute, bamboo, brass, nylon, pineapple leather, straw silk, cotton, glass—does offer a hanging collection of sorts, presented in various knots, weaves, textiles, and forms of joinery suspended around two primary structures. But any archival capacity is purely speculative, and the exhibition is more a staging of the conceptual possibilities of design than an accounting of historical documents. Nonetheless, histories saturate the work, and the invocation of many elegant lesser-known figures of twentieth-century art and design forms a network of influences tied together by Antunes’s own signature aesthetic.

As in her past work, Antunes addresses local contexts through visual and material citations that are direct, honorary, and respectful, in this case through the figure of Lena Meyer-Bergner, a designer who trained in the second phase of the Bauhaus and moved to Mexico in 1939. She was primarily a textile artist but was active in the graphic workshop, Taller de Gráfica Popular, which was famous for using printmaking to support anti-fascist and leftist political causes. The jute hanging grid that draws influence from Meyer-Bergner’s work tells us little that would recall her legacy directly, but it …

March 8, 2022 – Review

Valentina Diaz’s “The Intermittent Movement of Speech Acts”

Gaby Cepeda

A guide, dressed all in black, formally addresses the audience. Argentinian artist Valentina Diaz’s practice, the guide explains, relies on a series of inexact but exacting translations: specific mental states inspired hand-knitted costumes; knitting patterns are transposed into a musical score rendered on an old-school typewriter; this score is interpreted, according to a tempo kept by a metronome, as a choreography for performers dressed in the costumes. Diaz’s performances have long been characterized by such iterative mutations, a methodology emphasized in this exhibition: rather than wander around the space, viewers enter at specific times to follow the guide through a pre-planned sequence of rooms.

After the brief introduction, we are welcomed into a room surrounded by a soft orange curtain. The space is illuminated only by the projection of a new, 11-minute video version of one of Diaz’s performances, /A Å Æ )A(, dating from 2019. Two characters wearing black, triangular, and armless costumes whose hoods conceal the upper halves of their faces pace metronomically around a squash court’s symmetrical grid. One sports a small yellow triangle on their front and a large red one on the back; the other has a large yellow and large blue triangle on front …

January 18, 2022 – Review

Claudia Gutiérrez Marfull’s “There is No Paradise Without Snakes”

Gaby Cepeda

The idea of the periphery implies a metropolitan center around which everything revolves. As cities become ever-more expensive and policed, they effectively turn their poorer citizens into an extrinsic workforce, pricing them out of central areas and forcing them to commute. Claudia Gutiérrez Marfull’s textiles capture the sorts of exurban landscapes that workers who live in the peripheries are likely to witness daily. Her delicate embroideries in “No hay paraíso sin serpientes” [There is no paradise without snakes], made with chunky acrylic and natural wool on Aida cloth, depict neglected areas of Puente Alto, the most populous commune in Chile, on the edge of Santiago.

In one of the two 2020 works whose shared title lends the show its name, Gutiérrez Marfull represents an overpass leading nowhere atop a dry stream bed using tight, colorful stitches. The weeds are tall, the concrete bridge mossy. Graffiti dots the area, as do a few trees. A few dark, elongated clouds cross the blue sky. In the second embroidery of the same title, a graffitied concrete wall obscures everything but the red roof of a beige building standing in the background. Beneath the gray sky, a couple of yellow trees sit in …

March 25, 2021 – Review

“OTRXS MUNDXS”

Gaby Cepeda

The group show “OTRXS MUNDXS,” at Museo Tamayo, is a watershed moment: it’s the first standalone exhibition in the museum’s recent history to focus on young, local artists, all of whom work in Mexico City. Since the museum was founded in 1981, it has largely dedicated its spaces to promoting international artists and spearheading state-private alliances in the museum sector. That this inclusive, self-aware moment arrives in the throes of a pandemic, and likely out of institutional necessity rather than want, is unimportant. Is curating local—if only because of travel restrictions and vanishing state budgets—better than the usual fare of pre-packaged US exhibitions? It is to me.

It’s exciting to walk into a show full of familiar names and objects now comfortably nestling in the institutional bosom, which is why it is also disappointing that the conceptual bag into which these practices were thrown is so, well, generic. “OTRXS MUNDXS”—a non-binary spelling of the Spanish for “other worlds”—essentially attempts to other the work of 39 very different artists and artist groups and in doing so make the museum appear sympathetic to the zeitgeist. But there’s a contradiction in claiming these new practices as radical breaks with the past while …

September 4, 2020 – Review

Paloma Contreras Lomas’s “The Marshland of Souls”

Gaby Cepeda

As a real chilanga, born and raised in Mexico City, Paloma Contreras Lomas is familiar with the ultra-centralized bent in Mexican culture: how the images and discourse produced in the capital solidify into countrywide narratives through their reproduction in the media and popular culture. Her awareness of her own position as a white, middle-class urbanite, an artist who inserts herself into sites of Mexican rurality, is apparent in her critical approach to such typical representations as the rocky Durango mountains and brown-faced white men acting tough (as seen in so many Westerns); the Mexican state’s dispossession of impoverished rural areas on the pretext of “rescuing” them; the concomitant vilification/romanticization of drug-dealing men through the deep yellow filter beloved of Netflix cinematographers. These stereotypes come back to questions of displacement: the agency to tell stories rarely belongs to those who live them, as the stories of Mexico’s rural populations tend to be told by those who exist in geographically proximate but profoundly different realities.

Contreras Lomas’s work explores the liminal space that exists between real landscapes and the fantasies projected upon them. In her portrayals, that space becomes the site of what might be called an Extractivist Gothic. In the video …

June 12, 2020 – Review

Angela Su’s “Cosmic Call”

Gaby Cepeda

We are all aware of the circumstances that have led to the glut of reviews of online shows, as opposed to the usual fare of objects under bricks-and-mortar, and the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) has responded to them by creating Sala 10, a virtual exhibition space on its website. It’s worth noting the format: a series of two-week-long shows featuring video pieces, displayed on a floating screen that opens unprompted over a page divided into a grid with blocks of curatorial text, an extended interview with the artist, and links to further information and credits. The website has a vertical axis with images and text alternating on each side as one scrolls, and its similarity to the layout of Rhizome’s influential “Net Art Anthology” (2016–19) suggests the emergence of a generic online exhibition design. The combination of background information and work is fitting for an institution known for its dedication to academic research: the artwork as a piece in a contextual puzzle.

That being said, Angela Su’s Cosmic Call (2019) is phenomenal on its own terms. It was originally commissioned for “Contagious Cities,” an international cultural initiative funded by the Wellcome Trust to explore the connections between cohabitation, …

February 27, 2020 – Feature

Mexico City Roundup

Terence Trouillot

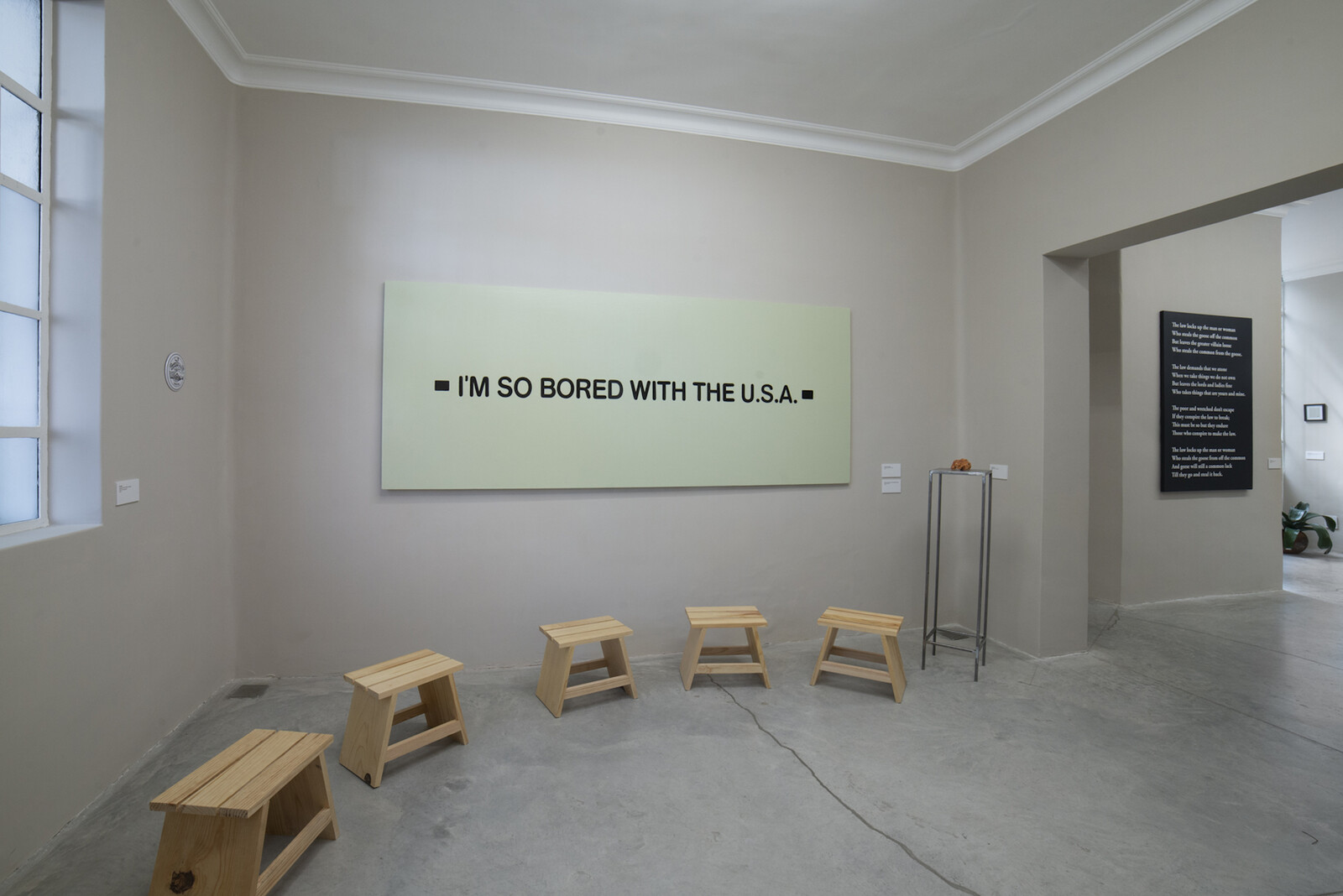

The title of Jim Ricks’s painting, I’m So Bored with the U.S.A. (2019)—borrowed from the Clash song—might be taken as a comment on how pervasively Mexico City’s Art Week has, in recent years, been dominated by the country’s relationship with its northern neighbor. This teal-colored canvas, the text of its title painted neatly against the surface in a sans-serif font, hangs at Daniela Elbahara gallery among a collection of the artist’s playful and witty works interrogating the structures of democracy and resistance. “This is What Democracy Looks Like” is the first painting show for the US-born Irish artist, whose conceptual work often incorporates sculpture and performance. The exhibition uses humor to lay bare the absurdity and hypocrisy of US politics, and to question the amount of attention paid to the country by the rest of the world.

Perhaps partly in anticipation of the cancellation of Art Basel Hong Kong, a surplus of American and European dealers and collectors were present during this major week of art fairs, gallery openings, and museum exhibitions. Pia Camil’s exhibition “Ríe ahora, llora después” [Laugh Now, Cry Later] was particularly popular with both visitors and locals. For her second solo show at Galería OMR, the …

October 15, 2019 – Review

Cristina Tufiño’s “Dancing at the End of the World”

Kim Córdova

Cristina Tufiño’s “Dancing at the End of the World” presents a grouping of drawings and sculptures that probe the violent effects of digital convenience and the gig industry. With pastel-glazed ceramic sculptures that feature anthropomorphized objects, feminine body parts, and cast-off keyboards, Tufiño adopts sex work as a metonym for the exploitative nature of the online economy. With an unsettlingly sweet aesthetic, she wonders about the consequences of using algorithms to mediate the instant gratification of desire on a vast scale.

In Constellation Sunset (Cubetas del Atardecer) (all works 2019), eggshell-blue arms lithely jut at rigor-mortis angles from two buckets filled with baby’s breath—the flower of innocence. A ceramic head of the same color is an eyeless but coiffed witness to the arms, which may be her dismembered limbs, her torso and legs unaccounted for. Peppermint Hippo (5) features two ceramic feet cleaved from an otherwise absent mint-colored femme, tied up with festive ceramic ribbons jamming a shrimp cocktail of long swollen toes over the edge of stripper heels a few sizes too small, highlighting the vulnerability to violence and the physical toll of desire-fulfillment work.

On the opposite wall, Bocaccio, a ceramic relief of a hand emerging from an arm-shaped keyboard …

June 11, 2019 – Review

Carsten Höller’s “Sunday”

Terence Trouillot

I was required to make a choice upon entering Rufino Tamayo’s famed museum in Chapultepec park in Mexico City. Wait up to an hour (or more) in line to crawl through Decision Tubes (2019), an interconnected web of mesh tunnels suspended in the sundrenched atrium that leads to different areas of the museum, or skip the wait and walk through Seven Sliding Doors (2014), a wall-to-wall mirrored hallway with automatic sliding doors that lead viewers into the main gallery space. These are the introductory artworks that open “Sunday,” Carsten Höller’s first survey in Latin America. Though the works in the exhibition all seem to promise a certain sense of amusement and playfulness, they are at best bewildering and surprisingly not fun.

This is not to say that Decision Tubes (myself and a group of friends finally decided to wait in line, begrudgingly) doesn’t spark a certain childlike glee, or at the very least a novelty experience, when awkwardly squirming through it. The work reminded me of a McDonald’s PlayPlace at every turn—a play area that most American children who grew up in the 1990s can remember with great fondness. But unlike its predecessor Decision Corridors (2015), a maze-like structure of …

March 5, 2019 – Feature

Mexico City Roundup

Kim Córdova

A man wearing pajamas and a bathrobe clutches a branded coffee mug and ponders the distance through the drawn curtains of the Museo Jumex terrace gallery window, his graying eyebrows knitted in maudlin unease. This is Mike, artist Michael Smith’s alter-ego who in the exhibition at Jumex, “Imagine the view from here!,” considers buying a “curated timeshare living experience” at the museum, marketed by the fictional International Trade and Enrichment Association. In promotional videos and trade fair–like booths, his bone-dry humor critiques the private interests that have a stake in the promotion of Mexico’s contemporary art scene to foreign and local markets as well as the clichéd banality of its consumption.

The show is particularly resonant in the context of Art Week CDMX, the annual week of cultural offerings organized to coincide with Mexico City’s art fairs. Playfully seeding his fictional timeshare with coopted real elements such as photos from past museum events, the omnipresent juice at the museum’s openings, and cameos by the museum’s curator, Smith constructs a conceptual art version of an investable real estate lifestyle package. The show’s trade-fair aesthetic is a reminder of how easy it is to harrumph fairs as too mercantile, too convention center ticky-tacky, …

February 14, 2019 – Review

“Nancy Spero: Paper Mirror”

Travis Diehl

Who was here first—Nancy Spero, or Hernán Cortés? It may be too much to call Spero (or anyone) a “universal” artist but her work certainly speaks to the weird postcolonial hybrids that survive as culture in the twenty-first century. Especially in this retrospective at the Museo Tamayo, a Brutalist building that shares a civic park and former world’s fair ground with Mexico City’s renowned Museo Nacional de Antropología, the scrolls, codices, and friezes that give form to Spero’s last four decades of printmaking—her Mediterranean references—make uneasy sense. In modern Mexico, layers of Spanish colonial, Aztec, and agrarian socialist civilizations build on the last’s rubble; for instance, a pre-contact, snake-shaped stone bowl fitted to a Mission era octagonal plinth becomes a font for holy water that is only superficially Catholic. Spero’s work, likewise, both matches and clashes perfectly with what’s already here. Thus the slight dissonance when you recognize in something like her series of figures dancing across long horizontal framed “scrolls,” such as Sheela and the Dildo Dancer (1987), the format of certain Mayan temple carvings. Whether this correspondence was the specific intent of guest curator Julie Ault and/or her Mexican hosts, or simply a kind of generic congruence of …

October 3, 2018 – Review

Gallery Weekend CDMX 2018

Kim Córdova

On the eve of Gallery Weekend 2017, at 11 a.m., sirens blared and a city of 22 million dutifully marched outside, allowing emergency team leaders to check and count them. Mexico holds an earthquake drill yearly on September 19, both a preparedness measure and a memorial to the 1985 earthquake that killed 5000 residents of the city. Two hours later, a rumble sounded like a passing jalopy semitruck. As it grew louder, the ground began to tremor, visibly churning the asphalt in the street. Those who could, ran outside into the roil. Electricity lines and lampposts lazily swayed, incongruent with the collective seethe of adrenaline. For a society accustomed to immediate information, the reality of the force of the earthquake was eerily delayed. The improbably perverse coincidence of a second devastating earthquake on the anniversary of the 1985 one remains diabolically astounding.

The next day it was announced that Gallery Weekend was postponed indefinitely. It would have been grotesque to consider forging ahead. Many of the galleries are located in some of the most seismically unstable land in the city. Situated on the bed of a massive drained lake, when the earth shakes the soggy ground turns to wobbling aspic amplifying …

March 14, 2018 – Review

Cerith Wyn Evans

Chris Sharp

I’m not usually a fan of art about art, for the simple reason that it tends to perpetuate the potential solipsism of a perilously self-involved discipline, but something about Cerith Wyn Evans and his consistent ability to transmute art-historical references into quasi-mystical arcana has always struck me as agreeably mystifying. As such, I feel like he cogently, if urbanely, conveys one of the greatest secrets of art: that it is a secret. Or at least this is what I tell myself while walking around his first monographic exhibition in Mexico, as people rush around to take selfies in front of elaborate neon sculptures hanging from the ceiling. Virtually and refreshingly devoid of didactic wall labels, the exhibition both secretly and not-so-secretly (if you are an adept of the cult of Art) teems with references to some of the more recondite practitioners of art in the 20th century. I can’t help but wonder how the general public gains access to works that directly cite Marcel Duchamp or Marcel Broodthaers? The short answer to my rhetorical question is: they don’t. And maybe that’s okay. Maybe it’s enough to obscurely intuit that just beyond the mere appearance of a given thing lies a …

December 7, 2017 – Review

Gallery Weekend CDMX

Travis Diehl

On September 19, 2017, Mexico City was hit by one of the most destructive earthquakes in the country’s history. Gallery Weekend Mexico City was originally scheduled to open September 21, by which time everyone who could was out in the streets clearing rubble and handing out food and water. The participating galleries met to formulate a response—the first time that they had come together to coordinate anything. The gala opening was called off, and it was decided to reschedule the event for November 9-12. Gallery Weekend also opened up: before the quake, exhibitors had to buy their way in; afterwards, organizers freely distributed purple markers bearing the #GWCDMX hashtag to anyone who wanted to join in.

Spanning a room at Galeria Enrique Guerrero is Adela Goldbard’s El salón de los pasos perdidos (2017), an airy stick-and-cardboard scaffolding in the shape of one of Mexico City’s most overbuilt civic symbols—the Monumento a la Revolución. The four-sided triumphal arch, guarded at its corners by the towering socialist-realist figures of workers, mothers, and architects, is in fact the cupola of an unfinished palace, re-appropriated by the people when the money ran out. The first stone was laid on Independence Day, 1910, the same day …

November 27, 2017 – Review

“Never Free to Rest”

Devon Van Houten Maldonado

What does it mean to present a group show of black artists based in the United States and United Kingdom—Mark Bradford, Charles Gaines, Rodney McMillian, Julie Mehretu, Kara Walker, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye—in Mexico City? Here, the white/black binary of racial discourse in the US and (to a lesser extent) Western Europe is complicated by the centrality of “mestizaje” (mixed ancestry) to the national identity. While this exhibition fails to fulfill its promise to “utilize the radical language of abstraction to destabilize black representation and systems of control,” it does offer the opportunity to reflect on some of the contrasts between postcolonial societies—whether real or imagined—in North and Latin America.

“In America, I was free only in battle, never free to rest—and he who finds no way to rest cannot long survive the battle,” reads the passage by James Baldwin that inspired the show’s title. But what this superficial collection of “hits” by popular black artists fails to consider is the context of both the country in which it is staged and the discourse that has shaped it: globalization and (post)colonialism as a double-edged sword. Globalization homogenizes and monetizes even as it makes possible new hybrid forms, like the jazz music Charles …

June 27, 2017 – Review

Kerry Tribe’s “the word the wall la palabra la pared”

Catalina Lozano

For her first exhibition in Mexico City, LA-based artist Kerry Tribe removed the front wall of Parque Galería and transformed it into a makeshift screening room. The crumbling architecture, with its exposed dry walls and frayed edges, introduces an exhibition in which seemingly solid physical and psychical structures are undone.

Tribe’s work addresses perception, memory, and language, as well as the technologies used to perceive, record, and describe experience. Combining video, sculpture, and photography, her latest exhibition considers how atypical circumstances—such as alterations in the mechanisms of reception and emission in the brain—create opportunities to analyze the norms by which fitness and unfitness are defined. By paying attention to the anomalous, Tribe tackles new, affective configurations of knowledge.

“the word the wall la palabra la pared” picks up and branches out from “The Loste Note,” Tribe’s 2015 show at 356 Mission, Los Angeles. Both deal with aphasia, a condition affecting the way oral and written language is processed. It is typically caused by damage to the brain, normally due to a stroke or head trauma. At Parque Galería, Tribe focuses on her collaboration with photographer Christopher Riley who, after two strokes, lives with the condition. In the video Afasia [Aphasia] (2017), both …

June 9, 2016 – Review

Nicholas Mangan’s "Ancient Lights"

Claudia Arozqueta

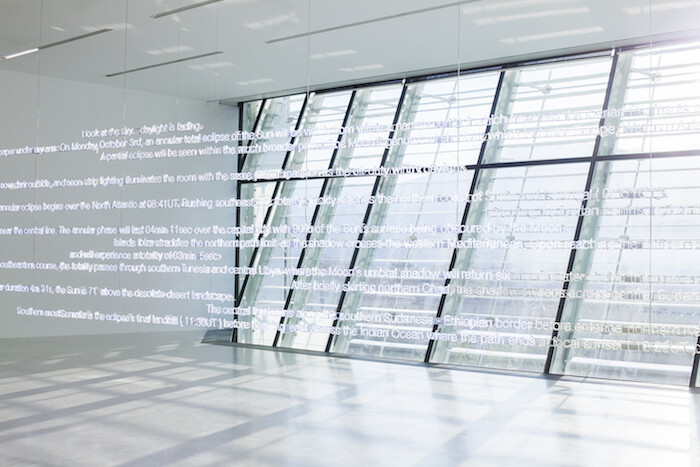

As the central body in our planetary system, the sun has been revered through history as the source of our energy and the basis of our calendars. “Ancient Lights,” Nicholas Mangan’s first solo exhibition in Mexico City, is a sun worshipper’s investigation into the myriad conceptions of our star, from the theological to the technological. It features an installation of two new films (both Ancient Lights, 2016), projected one in front of each other at different angles in this L-shaped gallery, which explore the unstable relationship between humanity and nature as well as different kinds of energies: motion, sound, electricity, and magnetism.

Scientists have long considered how solar variations—like sunspots—might relate to changes in climate and associated human activities. Mangan’s first film—displayed close to the gallery entrance on a suspended wall, at 90-degree angle to the room’s right wall—charts and compiles these investigations. The 13-minute loop presents a montage of different footage: the sun reflecting off the heliostats at the Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant in Andalucía; the air contamination visible in the skyline of Mexico City; audiovisual data from NASA’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory project, which tracks the relationship between sunspots and weather changes; oranges covered in frost during an unseasonable cold …

March 2, 2016 – Review

Andrea Geyer’s “Truly Spun Never”

Claudia Arozqueta

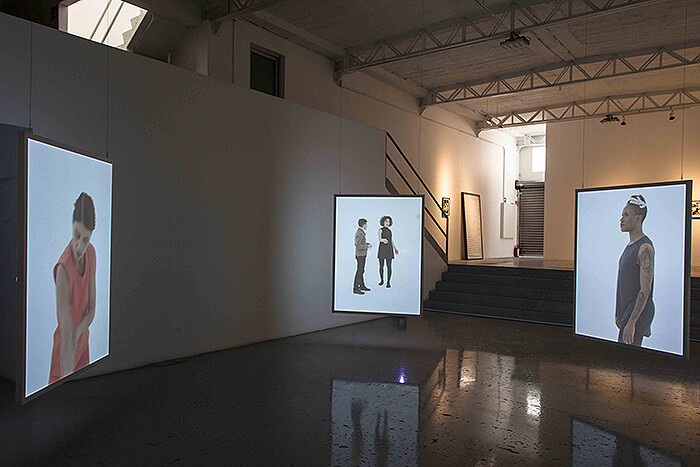

Like dance draws lines in space and time, Andrea Geyer’s first solo exhibition in Mexico City leaves a pleasant yet evanescent memory. Through crisscrossing imaginary and factual lines, the artist connects past histories and current politics with a sharp focus on the role of women in the arts. Encompassing a variety of media, such as video installation, photographic collage, and painting, “Truly Spun Never” is a theatrical show without being solemn or inviting the blues.

Entering the exhibition space, viewers can see four large-scale framed white paintings (Travels on Slender Thread 2–5, 2015) interspersed with black-and-white photographs lining the walls of the gallery’s foyer. Lazily leaning against the walls, the text-based paintings that constitute Travels all feature poems written by the artist, based on her extensive research into women’s under-recognized contributions to modernism. The texts themselves are dry, but their design, with two different sizes of fonts, suggests movement and different tones or tempos; interconnecting graphic lines imply the variety of modes of reading a single thing or fact.

Hung on the walls is the more effective “Asterism” series (2016): historical portraits of women who contributed to the Bauhaus—such as artists Anni Albers, Marianne Brandt, Gertrud Arndt, Lucia Moholy, and Grete Stern—all …

April 29, 2015 – Review

Ad Minoliti’s “CSH#14_utopía”

Carla Acevedo-Yates

“Queerness is not yet here”—at least according to José Esteban Muñoz, who in his book Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009) argues that queer aesthetics is fundamentally utopic. The same could be said for much of Ad Minoliti’s work, in which queer exchanges are understood not as acts of performativity between humans but as interactions between non-human forms and things, thus potentially structuring the social parameters of a future yet to come. Minoliti’s practice is concerned with painting as a space of resistance, in which gender-neutral relations manifest in anthropomorphic geometric entities that inhabit the tropes of modernist painting, design, and architecture, and, in doing so, unintentionally echo the all too familiar notion of failure often attached to modernist utopias. Ad Minoliti, formerly Adriana Minoliti (the artist recently started going by “Ad” instead of her full first name in an effort to avoid gender identification, thereby claiming gender neutrality), lives and works in Buenos Aires, where she is the co-founder of PintorAs, a feminist collective of 20 young Argentinian artists.

Inspired by the Case Study Houses (1945–1966), a project conceived to supply affordable and efficient housing to soldiers returning to the U.S. after the war, Minolitti turned …

November 20, 2014 – Review

Torolab’s “La Granja”

Claudia Arozqueta

The recent disappearance and alleged assassination of 43 students from Ayotzinapa Normal School in the southern city of Iguala, Mexico, has once again raised the alarms of an entire country already shocked and affected by corruption, violence, and poverty. But while for years organized crime has spread violence, the disappearances of citizens, and the sowing of corpses throughout the country—not on a few occasions under the tolerance or complicity of authorities—some initiatives seeking to restructure the country’s broken social fabric have simultaneously flourished across Mexico. Among them is the ambitious La Granja Transfronteriza [Transborder Farmlab], an experimental center created by the interdisciplinary artist collective Torolab—Raúl Cárdenas Osuna, Ana Martínez, Bernardo Gutiérrez, Enrique Jiménez, Shijune Takeda and Rodolfo Argote—aimed to establish and sustain models of fighting poverty and violence in Camino Verde, Tijuana, a low-income urban area that functions as a microcosm of Mexico: a space ridden with economic and social inequalities that lacks a sense of community, and where distrust between residents and authorities seems insurmountable.

The strategies undertaken by La Granja Transfronteriza to generate better living conditions in this segregated region started by building trust among its residents. Creative writing workshops were key to opening communication channels that allowed Torolab …

July 31, 2014 – Review

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané’s “/____/_//__”

Ana Teixeira Pinto

The Phasmida are an order of insects whose rocking march always seems hesitant. Every step they take, “stick insects”—as Phasmida are commonly called due to their resemblance to sticks or leaves—will reluctantly stretch out a leg, making cadenced, side-to-side movements as if tentatively rehearsing the next. Biologists will tell you their intention is to remain inconspicuous by mimicking the rustling of twigs, but perhaps they are simply world-weary.

In his 16mm film Phasmides (2012), Spanish-born, Brazilian-based artist Daniel Steegmann Mangrané trails a stick insect’s journey inside his own studio. Initially shot against a cluster of branches and foliage, the insect slowly sways out of its den. It makes its way across the floor and onto a table filled with primary structures and geometric patterns that reflect the formal vocabulary of modern art from Constructivism to Minimalism. Assuming the liveliness of these fixed geometries, the stick insect then blends into a background reminiscent of a Carl Andre or a Sol LeWitt.

Contrary to British naturalists Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace’s notion of an evolutionary adaptive value, Surrealist writer Roger Caillois described mimicry as a surrender to the “lure of space,” a “scattering of self across landscape,” rather than as a defense mechanism.(1) …

June 4, 2014 – Review

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s “Fireworks”

Chris Sharp

Having had the privilege of seeing the work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul in several different contexts (New York, Kassel, and even Bangkok), none have resonated with me so strongly and strangely as that of Mexico; how peculiarly apropos to see his new film in Mexico City. Shown among a furtive constellation of shorter and spatially slighter projections as well as a selection of lightbox photographs, Fireworks (Archives) (2014), the first part of a forthcoming trilogy of films, is clearly the main attraction of the Thai filmmaker and artist’s first solo outing at kurimanzutto.

This 6:40-minute film, which is projected on a large screen at the center of the darkened gallery’s main space, depicts Thai/Lao mystic, cult-leader, and sculptor Bunleua Sulilat’s (1932–1996) temple-cum-sculpture garden, Sala Keoku, located in northern Thailand close to the Mekong River. Passages of blackness sporadically dissolve under the fitful internal illumination of sparklers, which light up to reveal Sulilat’s unorthodox temple populated with a fantastical concrete menagerie of beasts and figures; the sculptures range from the broad, whale-like contours of a frog’s face, to a cavalcade of dogs on mopeds, to a pair of skeletons partially embracing as if sitting for a double portrait. These images are interspersed with …

April 21, 2014 – Review

Terence Gower’s “Baghdad Case Study”

Adam Kleinman

On May 13, 1846, United States President James K. Polk went before Congress and asked for a declaration of war against Mexico. His rallying cry: “American blood has been shed on American soil.” While eleven Americans were killed and six more were wounded in what is now known as the Thornton Affair, the official Mexican response considered the skirmish as an act of US aggression that actually took place south of the border. Whether or not the American people had been deceived, Polk—whose administration had already started plotting just such a war in advance—found his necessary pretext, and with it, America’s historic march into expansion-by-force began in earnest. If this strategy sounds oddly familiar, it might be wise to remember that March 20, 2014 was the eleventh anniversary of the second US invasion of Iraq, a premeditated war drummed up by the upper echelons of the US government in “response” to events that might not have happened exactly the way they said they did. By way of trans-historical testament, it is most fitting that Canadian artist Terence Gower now presents his Baghdad Case Study (all works 2012/14)—an encyclopedic work that parallels various post-WWII histories of US interventionism—in Mexico, the very …

November 22, 2013 – Review

Dispatch: Opening of Museo Jumex

Kevin McGarry

In the cosmos of art collecting, there are few private exhibitors as closely associated with a place (Mexico City) and an industry (juice products) as Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo. The thousand-and-one guests who descended on D.F. this past weekend for the lavish opening of collector Eugenio López’s David Chipperfield-designed Museo Jumex in the uptown neighborhood of Polanco were in for a very different experience than trekking ninety minutes (in good traffic) from the city center to the grounds of the Jumex factory in Ecatepec, where until now the Fundación’s galleries had been headquartered. The exhibition space at the factory still exists; a retrospective exhibition of the Danish collective SUPERFLEX is currently on view. But now the contemporary art collection, Colección Jumex—assumed to be Latin America’s largest—has put down roots in central D.F., rearranging the cultural geography of the Western Hemisphere’s most populous capital overnight.

Mexico City is blessed with a number of great contemporary art museums—Museo Tamayo, whether or not it ever expands, in Chapultepec Park; Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) on the campus of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) in the south; smaller institutions like Museo Experimental El Eco on Reforma and the non-profit Sala de Arte Público …

July 25, 2013 – Review

“A Trip to the Moon”

Chris Sharp

Despite the possession of a rich literary pedigree, the good old chicken-or-egg quandary of fact or fiction seems to receive limited play if not in the Latin American context, then the Mexican context of contemporary art (and by literary, I mean of course Julio Cortázar, and even more importantly, Jorge Luis Borges, who reveled in this mental stew regularly). Why is this? Well, beyond its origins in the critical re-evaluation of the promises of modernism, the theme seems to be the banal luxury of more politically stable climes, more at home in, say, Western Europe than in a region awash with unprecedented drug cartel violence and the albatross of responsibility that attends it. Given these conditions, such literary antics are liable to come off as politically irresponsible, all but rendering such ontological speculation a blithe, bohemian enterprise.

This charming group exhibition, curated by Fabiola Iza, manages to both sidestep and problematize such conceivable, context-specific political incorrectness by offering what could be perceived as a more nuanced perspective on said quandary. Entitled “A Trip to the Moon,” the show is positioned in-between two moments—the 1969 landing of Apollo 11 on the moon, a historic feat apparently riddled with doubt, and Georges Méliès’s …

April 16, 2013 – Review

Mexico City Dispatch: Zona Maco Sur and Gallery Openings

Gabriela Jauregui

The Zona Maco art fair week (April 10–14) got off to a good start with the notion of a nude bird at Etienne Chambaud’s exhibition at LABOR called “The Naked Parrot.” The path was there, the bird absent. Rainbow-colored bird shit, echoed in the emailed invitation image of multicolored pigeons, outlined a zigzag trajectory through the gallery, under a fragile crisscross of severed bronze heads punctured by steel beams, titled The Fractal Zoo (2013). It left us to wonder: who are the animals inside this gallery-turned-cage? The yellow-pink-orange-blue-green shit road (from pigeons which the artist had fed colored pellets) marked an auspicious beginning for the journey that would end at Maco itself, a journey which included a fauna of art goers from all over the world teetering through Mexico City, from one opening to the next, in high heels and spring suits.

But it was last Tuesday that truly marked the gallery opening marathon, starting with Edgardo Aragón at Proyectos Monclova. The highlight of his show, which focused on land rights and violence, mostly in his native state of Oaxaca, was what the artist called his “portrait” of Zapata, titled, appropriately, Zapata (2013): a black marble box containing earth from the …

January 29, 2013 – Review

Fernando Ortega

Chris Sharp

At the heart of this exhibition lurks a singularly misanthropic humanism. Never have I felt so simultaneously wanted and unwelcome, so integral and superfluous to a grouping of artworks. So delicate and poised are these pieces, and, in some cases, so potentially lethal, that the comparatively graceless human figure seems offensive here, a volume somehow too inexact to sustain such severe precision. And yet the nine works that comprise this show are not so defenseless as that. Despite their materially slight and patently conceptual character, they wield a presence that is categorically sculptural, if only by the sheer tension they potently generate.

Take, for instance, the four-part Harmonic Variations (2013). This supremely fragile installation continues the artist’s ongoing preoccupation with musical instruments—instruments, that is, which are more often than not, paralyzed by his interventions. It consists of four different variations of harmonicas wedged between sheets of glass, placed no less precariously on ledges, which are held in place by nothing more than gravity. Indeed the subtlety with which Richard Serra becomes a kind of etherealized spiritual father here speaks to how sculptural this work is. That triggersome (to coin a neologism) sensation carries on with more open humor in a series …

November 6, 2012 – Review

Jean-Marie Perdrix’s “A Carne Perdida"

Chris Sharp

One thing I have noticed about Mexico is a proclivity to let no part of an animal go to waste. Just the other night, I was in a famous twenty-four-hour taquería, El Borrego Viudo, and on the menu were not only cabeza (lamb’s head) and lengua (beef tongue), but also sesos (need I translate?). It is perhaps only a coincidence that the work of Paris-based artist Jean-Marie Perdrix abides by a similar ethic, but a coincidence that nonetheless sits comfortably within the local context. That ethic, however, is anything but straightforward.

Take, for example, one of the sculptures on view here, the large djembe drum (Untitled, 2011). This apparently unremarkable object represents the years of research in Burkina Faso, during which Perdrix sought a means to recuperate and put to good use the over-abundance of plastic trash bags that afflicts the region like a plague. Having developed a non-toxic technique to melt the plastic down into a solid material, he has also found structurally and culturally relevant uses for it, such as for the making of crossbeams and djembe drums. Both an emblem of civic virtue and a process-driven sculpture, the dynamic object would seem to be unsullied by any but …

July 23, 2012 – Review

"Sinking Islands"

Tyler Coburn

With Katinka Bock, Etienne Chambaud, Hernán Díaz, Fabien Giraud, Karl Holmqvist, The Institute for Figuring, and Nicholas Mangan.

In the keynote essay for “Sinking Islands,” on view at LABOR, Mexico City, curator Vincent Normand provocatively asks, “What would be an exhibition of things flat-out alone, requiring the presence of no one?” We subjects of modernity, it would seem, are the problem this group exhibition seeks to critique, less in directly attacking the discursive means by which we have named and, thus, delimited the world, than by presenting objects that attempt radical breaks from signification, dipping beneath semiological horizons by weight of material intransigence. On account of their resistance to making sense for us, these objects assert a non-anthropocentricity that supposedly demands a self-othering, a becoming-savage of us exegetes. While Normand’s rhetorically encumbered text claims to depart from the promise of Utopia that, in cases like Thomas More, once anchored this topographical conceit, his wish for an insular thingness, in “the ocean of signs,” offers, at best, a cogent prompt of the exhibition’s works; and, at worst, a call-to-withdrawal befitting the conservative position of this cultural moment.

“Sinking Islands” takes form as both an exhibition and takeaway book, the latter of which shares …

April 19, 2012 – Review

Zona Maco

Kate Sutton

Art fairs—unlike biennales—aren’t allowed the luxury of an “off year.” And so it is that Zona Maco finds itself sandwiched between two Very Big years—with the opening of Carlos Slim’s Soumaya Museum last year and the debut of the David Chipperfield-designed facilities for La Colección Jumex slated for 2013. Now in its eighth year, the fair provides a much more relaxed alternative to Art Brussels and Art Cologne. But just because a fair takes lunch breaks—four hour ones at that, and always at Contramar—doesn’t mean it can’t be taken seriously.

As the Soumaya and Jumex museums chart out new territory for art in the city, galleries and smaller projects are gravitating towards older ones. In the Ampliación Daniel Garza area, just south of Chapultepec Park, Casa Luis Barragán serves as the elegant anchor for a fresh crop of initiatives, two of which opened Monday, two days before the fair. I started off at Labor’s new space, housed in the former workshop of Soumaya architect Fernando Romero, who has since moved next door to Casa Barragán, directly across the street. “I love how this address acts as a type of filter,” Labor’s Pamela Echeverria sighed between sips of mescal. “The type of …

March 21, 2012 – Review

Aleksandra Domanović & Sharon Hayes

Catalina Lozano

Aleksandra Domanović’s practice analyzes socio-political transformations through the production of images and narratives largely based on popular culture. By decontextualizing and reconfiguring media content, Domanović delves into the accumulative nature of information and its intrinsic indexicality. Like many artists born on the communist side of the Iron Curtain, she is interested in the difficult transition towards capitalism and the emergence of new social values, and, in specific, in the case of former Yugoslavia (where she was born), how this is all exacerbated by the outbreak of an ethnic and nationalist war.

At Proyectos Monclova, Domanović presents 19:30 (2010–11), a two-channel video projection which articulates two heterogeneous sets of imagery: the opening titles of several regional news networks of the former Yugoslavia and a stream of shots of techno raves, which emerged in the same region, like in many other places in the 1990s, as a strong part of youth culture. This unlikely marriage of references is materially and conceptually made possible through the soundtrack, a remix of the news jingles made by techno DJs. While the series of opening titles evoke the socialist era of information distribution, the raves manifest forms of collective social venting in this “new” society.

Watching the work, …

February 2, 2012 – Review

Karl Holmqvist’s “The Hours of This Watch is Numbered”

Chris Sharp

“I WANT DANDY.” There’s no denying that it’s appealing, even catchy, not as catchy perhaps as the maddeningly infectious pop song of which it is a jeu de mot, but catchy in a way that goes beyond an inane, knee-jerk impulse to sing it. Or maybe perplexing is a better way to describe the neon sign hanging in the storefront window of Karl Holmqvist’s second show at this gallery. What does it mean? Is it trying to sell me something? Or is it articulating desire? But whose? And isn’t it a contradiction of sorts, given that the nature of the dandy is to be so blasé as to be beyond, well, wanting?

Clues to this mystery can be found in the rest of the exhibition, which, with beguiling obtusity, is entitled: “The Hours of This Watch is Numbered.” Clearly mindful of the fact that this gallery is located in a barely repurposed boutique, the poet-cum-artist Holmqvist has created an exhibition whose discrete sellable parts, with the exception of a video, are hard to identify—the general, seemingly anti-commercial mood being one of sophisticated aftermath, calculatingly casual, spontaneous, and unruly. With concrete poetry inspired graffiti all over the walls and on a couple …

April 16, 2011 – Review

Zona Maco, Mexico

Adam Kleinman

While considering the strange juxtaposition of the skyscraper’s program, architect Rem Koolhaas—in his 1978 Delirious New York—speculated that the ‘plot’ of the Downtown Athletic Club’s ninth story was a tale of “eating oysters with boxing gloves, naked.” Similarly congested is the exposition hall, which these days can be found hosting art shows, boating events, music fairs, and so on. Yet Zona Maco and its host, Centro Banamex, layered not only a hippodrome with an art fair, but added a children’s expo, a high-end car parts show, and a security systems fair extravaganza. As such, last week’s festivities presented the opportunity to take your kid to sample unreleased Nintendo games, while perhaps also lavishing a trifecta payout windfall on add-ons for a super and/or muscle car, a new painting or designer desk, while at the same time picking up a new alarm system to guard the loot. Adding a comical flair to this surrealist cut-up, many “test” sirens could be heard sounding off and blending into the aptly named “zone” of the art far. Although Koolhaas lauded the social potentiality that these chance cross-programs offered, Hal Foster—in his essay Bigness from the London Review of Books*—famously questioned this legacy of celebrating …

January 13, 2011 – Review

Allora & Calzadilla at Kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Adam Kleinman

When viewing Compass, I had an uncanny feeling of being lost. Part of this had to do with the theatrical power of the work, yet a sense of dread came over me as I realized that this was actually a restaging. Although it is great to revisit a work, this new context leads to some measure of troubling questions. Namely, in this re-presentation, the artists had swapped out the video that was paired with the work the first time—and, in so doing, provided a problematic relation. This change makes a world of conceptual difference when considering the artists’ oeuvre and their practice, which is charted toward Venice to represent the USA for the next Biennale, but also makes an accidental commentary on the art industry as a whole.

When entering Compass, the viewer is presented with a vast empty space that has been bisected by a dropped ceiling, dividing the gallery into two levels—a narrow skylight allows light to filter from the top a la Louis Kahn and Tadao Ando. Other than the light, the lower level is entirely empty, save for a similar bleed in sound seeping in from above. What we’re hearing is the scuffling of dancers who take …

Load more