Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

December 22, 2023 – Review

Pacita Abad

Tausif Noor

To discuss the life of Pacita Abad is to enumerate the diverse places to which she traveled (some sixty countries across six continents), her expansive artistic output (nearly 5000 large-scale works), and the litany of materials and techniques she applied to the surfaces of her signature stuffed-and-quilted canvases, or trapuntos (sequins, beads, batik prints, and phulkari embroidery, to name just a few). Over a thirty-two-year career—she died of cancer in Singapore in 2004—Abad sidestepped hierarchies between craft and high art and unraveled received notions of the local, national, and global, pursuing instead a vibrant eclecticism that was often at odds with the dominant artistic movements of her time.

The retrospective at SFMOMA—arriving from the Walker Art Center before stops at New York’s MoMA PS1 and the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto—follows Abad’s artistic career as it was shaped by global postwar politics from the aftermath of national decolonization movements in Asia and Africa in the 1960s, through the humanitarianism of the 1970s and ’80s, and the heyday of multiculturalism in the US in the 1990s and early 2000s. In this, Abad’s trapuntos in particular function as what the curator Shabbir Hussain Mustafa has aptly termed an “archive of the …

June 28, 2022 – Review

Hernan Bas & Zadie Xa’s “House Spirits”

Danica Sachs

There’s a spot in the two-person exhibition “House Spirits” from which Hernan Bas’s large-scale painting Disco Demolition Night (all works 2022) appears framed by Zadie Xa’s shamanic robe Kimchi rites, kitchen rituals, hanging near the front of the gallery, and her kaleidoscopic constellation in stitched linen-and-denim, Seven full moons, on the back wall. In this sightline, the artists seem an unlikely pairing: the content and references of Xa’s fabric works draw on her Korean heritage while Bas’s acrylic paintings are rooted in white American pop culture. In bringing these two artists into dialogue, however, this exhibition foregrounds the way each traffics in a kind of visual folklore. The tension between the former’s new, hybrid identities and the latter’s melancholy depictions of the demise of a monolithic culture reflects changing social dynamics.

Two of Xa’s brightly colored robes hang opposite each other, suspended from the ceiling. The open folds on the front of Princess Bari fall in concentric half circles, made of linen hand-dyed in shades of coral, chartreuse, and sky blue, the hues seeping together to create a riotous sunset. The back is festooned with stitched knives and a cascade of rainbow ribbons running down the back, each ending with …

April 8, 2022 – Review

Andrea Bowers’s “Can the world mend in this body?”

Brian Karl

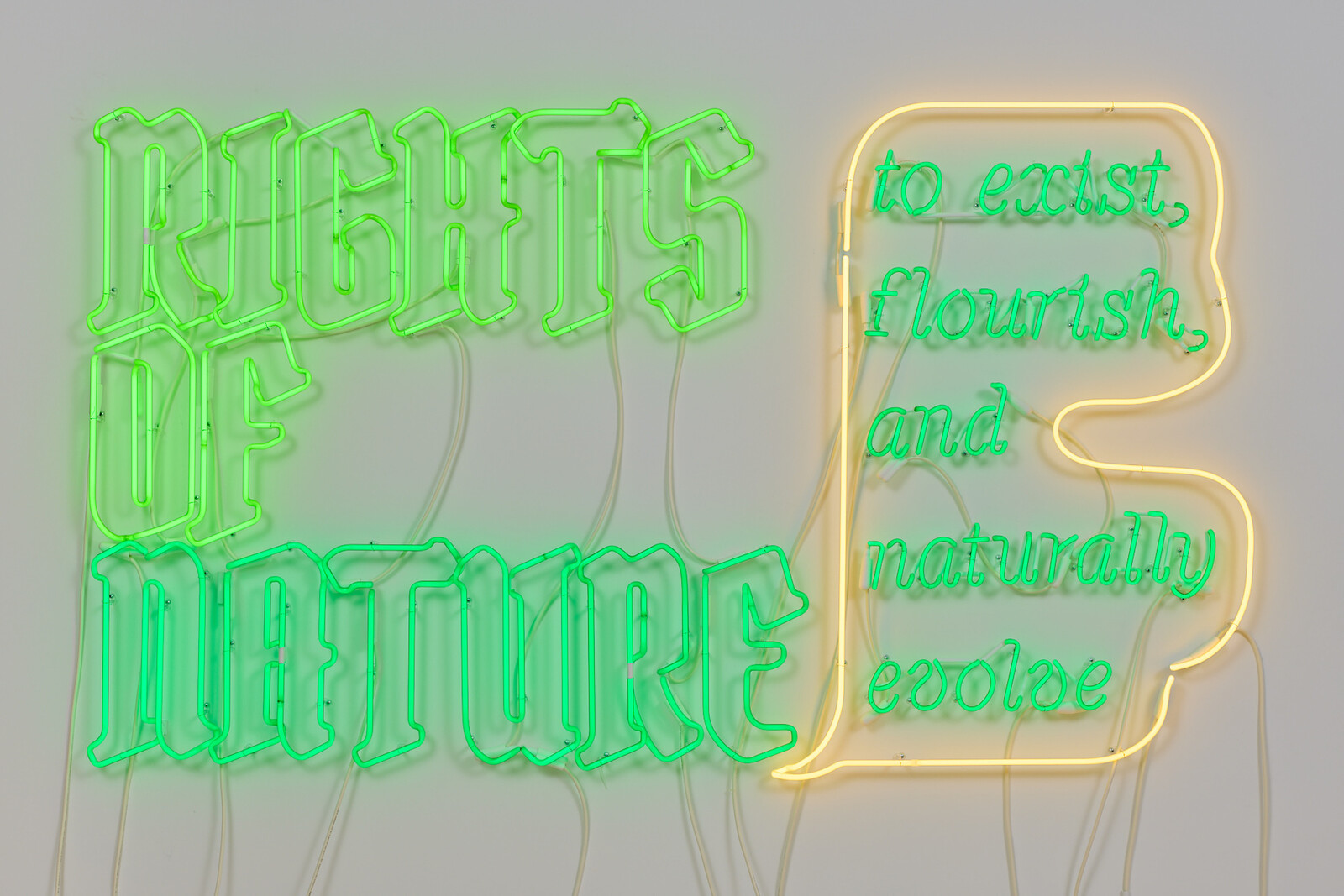

Andrea Bowers’s solo show at Jessica Silverman is marked by the artist’s signature combination of directness and nuance. Rooted in eco-feminist engagement and employing a wide range of media—neon signs, drawings on recycled materials, and video documentary—her deftly radical work calls attention to environmental degradation caused by patriarchal systems.

Bowers’s wall-mounted sculpture Rights of Nature I (2022) glows at passersby through the gallery’s street-level storefront window. Green neon tubing, styled in antique Gothic font, evokes legal documents while limning the piece’s title phrase. This in turn seems to emit a yellow speech bubble framing the words “to exist, flourish, and naturally evolve” in a contrasting font. This work builds on the use of neon by an earlier generation of artists—Deborah Kass and Bruce Nauman among them—as a communicative medium for political commentary, while continuing to play on and against its conventional employment in commercial signage. Though less dynamic than some of Bowers’s previous witty and sharply political slogans in flashing multicolor lights, it is among her most substantial: a heartfelt and lucid declaration that the Earth and other living creatures should be afforded the same rights, ethical treatments, and legal protections as humans.

Within the gallery, a sister piece is …

January 13, 2022 – Review

Sonya Rapoport’s “Fabric Paintings”

Danica Sachs

In 1970, Sonya Rapoport unlocked an antique architect’s desk she had purchased a decade earlier and discovered a trove of geological survey maps from the early 1900s. Using the information on the maps as a starting point, Rapoport began drawing and embroidering directly on the sheets in what she called her “Nu Shu language,” a visual lexicon the artist developed in reference to a tongue used only by women in the Hunan region of China. As the artist tells it in a 2006 essay, this moment marked an aesthetic shift, opening a new line of creative inquiry that would anchor her practice for decades.

The artworks exhibited at Casemore Kirkeby, however, make clear that in fact there were inklings of these developments a few years prior to the artist’s revelatory moment with the maps in the desk. Here, in a selection of sculptural paintings made from 1964 to ’67, Rapoport uses upholstery fabric as her primary substrate, both for tracing the gaudy floral patterns in paint, and for stenciling curvilinear, abstract forms that mark the first instances of the artist’s transcription of her visual language into her artwork. Viewed alongside several drawings made during the same period, the exhibition reveals …

February 24, 2021 – Review

Rosie Lee Tompkins

Amelia Lang

I learned about the life and quilts of Rosie Lee Tompkins (the pseudonym of Effie Mae Howard) from my mother. She was an art teacher—my art teacher—and would routinely give short presentations about local artists, usually women, to teach her students about art made in Northern California. I knew that Tompkins was born in Arkansas in the 1930s, had settled in Richmond, California, and that her work was considered part of an African American quilting tradition, but I had never seen the quilts in person until early March 2020, when I visited the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) to view “Rosie Lee Tompkins: A Retrospective.” The previous day, the Grand Princess cruise ship had pulled into the Port of Oakland carrying thousands of passengers exposed to the novel coronavirus; I walked through the museum in suspense, my thinking fragmented by constant notifications about the future. Yet Tompkins’s quilts pulled me into the present: I was mesmerized by the nearly seventy works on display, which revealed her fascination with color, the consistency of her inconsistency, and her use of fabrics that carried with them generational shorthands depending on pattern, texture, and material.

Nearly a year later, a small …

March 27, 2020 – Review

Lydia Ourahmane’s “صرخة شمسية Solar Cry”

Fanny Singer

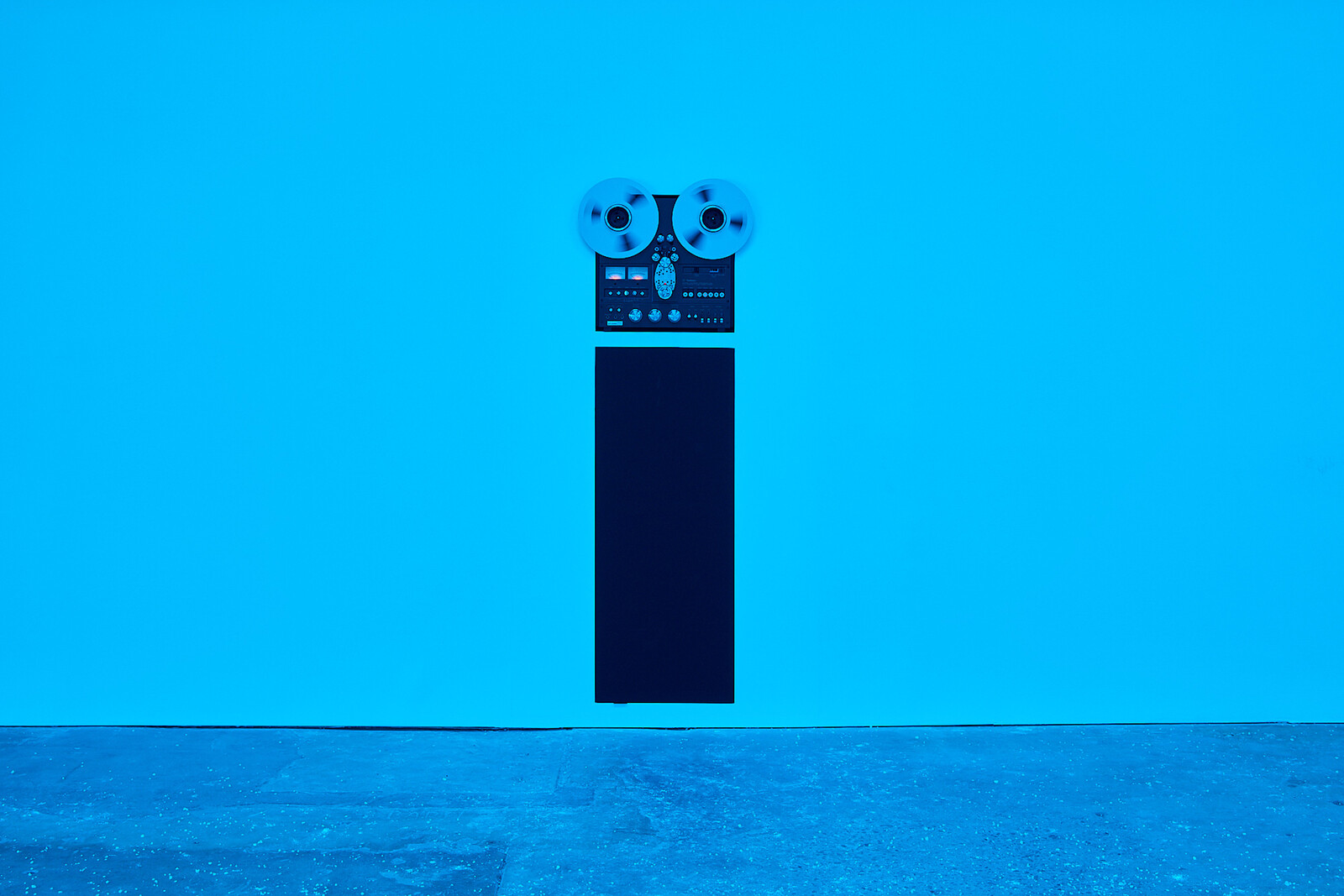

The second time I visited Lydia Ourahmane’s exhibition I was alone save for the young student-docent sitting at the front desk wearing earphones. Standing in the cavernous, quasi-industrial space—most of the internal walls had been removed—it felt appropriate that the last show I expected to see in a long time should be a near-empty room flooded with blue-tinged light (the front windows and skylights are laminated in sheer cobalt film) in which two tape decks mounted on opposite walls play recordings of an opera singer holding one note, and then another. The exhibition took on an elegiac air; the sung notes—a spare, tonal fabric—assumed the weight of lamentation.

This cyanic atmosphere reminded me of visiting Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s retrospective at Paris’s Centre Pompidou, a few days after the citywide attacks of November 2015, through which played a soundtrack of rain. I read the recorded deluge as an aural landscape of mourning, a kind of liquid dirge. That the current climate of fear has been triggered by something invisible to the naked eye—a viral “parasite” so minute that 50,000,000 could fit on the head of a pin—feels germane in the context of an exhibition made by an artist who prizes the ineffable, …

February 20, 2020 – Review

Rashaad Newsome’s “To Be Real”

Monica Westin

I learned from Being (2019)—an artificial intelligence that Rashaad Newsome has trained with texts from theorists and cultural critics including bell hooks, Frantz Fanon, and Michel Foucault—that slaves and robots have one foundational thing in common: “They are both intended to obey orders.” Being is nestled in a small dark screening room behind the immersive installation at the heart of “To Be Real.” Its intelligence doesn’t require a body, it reminds me twice, but Newsome has created one for it using 3D modelling software: a metallic humanoid form with visible cords and plates like a steampunk skeleton, and an incongruous wood-textured face dominated by oversized eyes characteristic of an Angolan Chokwe mask. Via computer projection onto the main screen, Being responds to questions I ask into a microphone set up in the middle of the room; like any good chatbot, it redirects to its message regardless of what I ask. While it speaks, its torso swings around languidly, as though dancing or floating.

As a dematerialized, entirely virtual android, Being serves as a nonhuman figure par excellence, the analytic center of an exhibition devoted to Newsome’s examination of dehumanization. This survey is thematically expansive, interrogating race, gender, and sexuality through a …

January 14, 2020 – Review

Daria Martin’s “Tonight the World”

Brian Karl

We dream in the dark. Repressed memories, daily conflicts, ghosts, and other spirits surge while, unconscious, we sleep, eyes closed. Dreams haunt our waking lives too, though usually with faint traces. Most people remember little of their dreams, and share even less with others. Likewise, audiences have grown accustomed to watching the products of culture industries’ dream factories in closed-off places where little daylight shines: isolated screening rooms in cinemas, art galleries, and museums, in which chosen imagery and objects are foregrounded while much else gets elided.

In “Tonight the World,” Daria Martin teases out fragmentary dreamwork with thoughtful and accomplished layering of history and impressions that both make possible and deny fuller interpretation. The exhibition’s darkened setting lends it the atmosphere of an interior dreamscape, while its overall ambit parallels the unconscious’s processing via dreams’ disjunctive, transformational, and ineffable logics. Martin’s exhibition elaborates conscious attempts by her grandmother, the artist Susi Stiassni, to capture in writing her own dreamwork’s traces. Stiassni kept a dream diary that accumulated over decades to 20,000 typewritten pages, from which Martin has culled five episodes exploring her anxiety about intruders.

The central, large-scale projection of a short live-action film from which the exhibition takes …

November 14, 2019 – Review

Hannah Collins’s “I Will Make Up a Song”

Monica Westin

In 1945, Hassan Fathy, an Egyptian modernist architect and pioneer of sustainable design, was tasked with relocating 7000 residents from the village of Gourna, on the West Bank of the Nile, to a new site several miles away. The original town of Gourna was built on top of a tomb that residents had been illegally raiding to support the local economy for generations; eventually, government authorities commissioned the massive rehousing project in order to preserve what was left of these artifacts.

In his 1969 book Architecture for the Poor: An Experiment in Rural Egypt, Fathy describes the daunting task of creating the entirely new municipality of New Gourna: “All these people, related in a complex web of blood and marriage ties, with their habits and prejudices, their friendships and their feuds—a delicately balanced social organism intimately integrated with the topography, with the very bricks and timber of the village—this whole society had, as it were, to be dismantled and put together again in another setting. […] It was uncanny enough that a whole village should be projected without reference to the State Building Department, but it was even more unnerving to find myself with the sole responsibility for creating this village.”

Fathy …

July 3, 2019 – Review

Suzanne Lacy’s “We Are Here”

Monica Westin

The dominant form of Suzanne Lacy’s work is dialogue. Deeply collaborative and painstakingly structured without being scripted, the conversations she produces combine formal elements of happenings (Allan Kaprow was one of her mentors) with politically focused content that is often activist in approach and always attuned to power as it plays out in the lives of everyday people. Lacy came of age as an artist during the beginnings of feminist art (she left a career in zoology to study with Judy Chicago), and her work from the 1970s first foreshadowed and later shaped much of what we now call social practice. Her thought has also been deeply intersectional long before most white feminists learned about the concept.

“We Are Here,” Lacy’s first major retrospective, is massive, spanning two very different institutions in San Francisco. (Currently based in Los Angeles, Lacy was previously the chair of what is now the California College of the Arts in San Francisco.) Curators from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts co-organized the exhibition, and the two arrays of Lacy’s work in their galleries offer different curatorial approaches to presenting an opus that itself operates largely as a …

October 31, 2018 – Review

Haroon Mirza’s “The Night Journey”

Monica Westin

The source material for The Night Journey (2018), Haroon Mirza’s sound-based multimedia installation, is a miniature painting from the collection of the Asian Art Museum that is conspicuously absent from the final exhibition. The original painting, The night journey of the prophet Muhammad on the heavenly creature Buraq, created in India around 1800, depicts Muhammad on his journey from Mecca to Jerusalem with his face unveiled: a type of representation that has often been prohibited on the grounds that images of the Prophet can encourage idolatry. There is a roughly contemporaneous miniature painting of Muhammad included in Mirza’s exhibition: this one is, pointedly, veiled.

The theme of iconoclasm—the destruction of images—is thus woven into Mirza’s installation, which teases out from the perennial contentiousness of representing religious figures a more formal question, asking how the relationship between a subject and abstracted information extracted from it and converted into another form can be understood, whether as an appropriation, another type of depiction, or a form of censorship. In other words, iconoclasm is a starting point for the artist’s exploration around the limits of translation that transcend ideology into form.

Mirza’s exhibition “The Night Journey” includes a pixelated inkjet printout of the c. 1800 …

May 9, 2018 – Review

Ken Lum’s “What’s old is old for a dog”

Monica Westin

Ken Lum is a prolific writer as well as a conceptual artist, deeply attuned to semiotics across media, whose past work includes a series of “language paintings” that depict nonsensical words in colorful designs. He would probably be amused to hear that I turned to the Oxford English Dictionary while trying to reconcile the seemingly divergent bodies of work currently on display at the Wattis Institute.

The exhibition “What’s old is old for a dog” (as far as I can tell, an invented idiom very much in keeping with Lum’s other fictional deployments of signifiers) is divided in two by a temporary wall in the middle of the main gallery. Each space contains formally and thematically distinct sets of works separated by over a decade. The first comprises Lum’s earlier and more familiar pieces, which experiment with how individuals convey or project identity through language conditioned by class. These include his 2001 “Shopkeeper Series,” simulacra of small business signs spelling out messages of quiet desperation in short word limits (like “SUE, I AM SORRY/ PLEASE COME BACK” beneath a sign for “Jim & Susan’s Motel”); several photographic portraits of real and fictional characters from the “Historical, Youth and Attribute Portraits” series …

April 13, 2018 – Review

Matthew Angelo Harrison’s “Prototypes of Dark Silhouettes”

Jeanne Gerrity

In an early scene in the recent blockbuster hit Black Panther, the black supervillain Erik Killmonger disputes the narrative spewed to him by a supercilious white curator regarding an African artifact on view in the “Museum of Great Britain,” asserting instead that it is a spoil of war from the (fictitious) country Wakanda. Immediately following their verbal exchange, she drops dead from poisoned coffee, and he repossesses the pillaged object in an elaborate heist. This example from popular culture demonstrates that the need to address the complicity of western museums in colonialist narratives has reached beyond the confines of the art world. The complicated politics of museum display are one of several interconnected issues—including commodification and authenticity, the role of industry and labor in cultural production, and black identity—that Detroit-based Matthew Angelo Harrison addresses in his first solo commercial gallery exhibition.

Twelve sculptures of varying heights comprise “Prototypes of Dark Silhouettes” at Jessica Silverman Gallery. Mounted on minimalist pedestals made of anodized aluminum legs and acrylic tops, tinted resin blocks that evoke the translucent geometric forms of the Light and Space movement encase what appear to be African art objects. The figures, heads, and masks are visible through varying levels of …

April 20, 2017 – Review

Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s “American Mystic”

Brian Karl

Capturing the unseen has been a taking-off point for photographic ambition since the medium’s inception. Ephemeral moments, underlying truths, and the supernatural have all been teased out through choices around opening and closing shutters. Featuring small-format photographs produced from the mid-1950s through the early ’70s, this exhibition at Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, posits Ralph Eugene Meatyard as an eccentric visionary who pursued and even contrived to generate signs of humans’ unseen and uncanny relationships.

The black-and-white tones in Meatyard’s photographs hold forth something immanent that is not quite real, lived life. The choreography for his images—almost all of which deny clear viewing, by one means or another—play on the voyeuristic aspect of photography. The obscured and recumbent human figure is one recurring posture that Meatyard set up and captured, often with the suggestion of other figures above or nearby (at the very least, the implied viewer/photographer). This is the case with the buckskin-dressed boy half-sprawled in tall weeds below a hulking water tower in Untitled (ca. 1955); in Untitled (1960), sunlit graffiti carved on a slab of wood confronts the viewer as if from the fever dream of the boy over whom it hangs, immediately above the dark shade in which …

October 28, 2016 – Review

Suzanne Blank Redstone’s “1960s Portal Paintings”

Leigh Markopoulos

Fifty years after painting the earliest work in this exhibition, Suzanne Blank Redstone has her first solo show. The name may be unfamiliar, but her work at first glance appears to participate in a recognizably twentieth-century art-historical dialogue. Featuring primary-colored geometric forms and grids, her compositions instantly evoke Piet Mondrian, at the same time hinting at a venerable tradition of European pre-war geometric abstraction of the sort practiced by Jean Hélion. While her experiments with illusion and perspective take part in an even older lineage, there’s also a nod to Surrealism evoked by incongruous René Magritte-like clouds occasionally softening the otherwise hard-edge constructions.

Despite these superficial resemblances, the works in this show reflect less about art history than the artist’s own triangulation of space and color. Seven of the ten paintings and all of the drawings on display at Jessica Silverman Gallery derive from “Portal,” a series of 38 paintings made between 1966 and 1969, each accompanied by between three and ten preparatory drawings. In addition to the intentionally restricted red, blue, and yellow palette—relieved by black, white, and a grey mixed from the other pigments—Redstone’s formal vocabulary encompasses rectilinear shapes and grids aligned exclusively along 45 and 90 degree axes.

Setting …

December 1, 2015 – Review

Letha Wilson and Richard T. Walker’s “The Distance”

Jeanne Gerrity

In a diminutive space in San Francisco’s financial district, the tradition of representing the vast landscape of the American West is extended and reinvigorated by Richard T. Walker and Letha Wilson. The natural and the manmade collide in Walker’s multimedia sculpture the other side of meaning something other than this (2015) and Wilson’s three photo-based wall works. Formally connected through repeated slanted lines and hints of geological forms, the pieces in the exhibition reference the past while operating very much in the present. Tied to conventional art forms like straight photography and landscape painting, the works nevertheless resolutely deny medium specificity through an unorthodox juxtaposition of materials.

A glowing white neon tube rises from a bass amplifier, draws the stark outline of a mountain across the gallery window, and returns into a pedestal holding a walkie-talkie balanced on an unremarkable rock that depresses an “A” note on a Casiotone keyboard. A similar, slightly larger rock several feet away is bounded by a thick black cord that stretches up to the ceiling and then hangs down, weighted by an inverted microphone. The rocks, collected in Nevada, connect the mechanical sculpture to the natural environment. The subtle sound enveloping the small room is …

January 5, 2015 – Review

José León Cerrillo, Ilja Karilampi, and Paul Chan

Jeanne Gerrity

Paul Chan is clearly energized by the Greek word polytropos. Homer used the word, translated as “cunning,” numerous times to describe Odysseus. This information, conveyed by Chan to a rapt audience during a two-part lecture, was included in the opening-week program for the new gallery Kiria Koula in San Francisco’s Mission District. The talk, Odysseus as Artist, drew parallels between the position of the Greek hero—stranded far from home and tempted by the seductions of material wealth—and that of contemporary artists, who must use their “cunning” to succeed in an increasingly market-driven global art world. This improbable but convincing metaphor is apt for Kiria Koula, a commercial gallery and bookstore committed to supporting new work and research in the spirit of a non-profit.

Along with Chan (who selected texts related to his research on The Odyssey for visitors to browse and potentially purchase), Mexican artist José León Cerrillo and Swedish artist Ilja Karilampi inaugurate the converted laundromat with visually disparate works connected by a focus on language and iconography. Cerrillo presents four glass panels containing geometric graphic symbols (all 2014)—what he dubs as “poems”—which are attached at right angles to a wall bifurcating the main gallery space. Three thin spray-painted iron …

November 18, 2014 – Review

Katarina Burin’s “Pre-arranged Comfort

”

Mariah Nielson

Models are used in architectural practice to represent and communicate ideas. In “Pre-arranged Comfort,” artist Katarina Burin transforms San Francisco’s Ratio 3 into a 1:1 model that proposes an exhibition of the work of designer and activist Fran Hosken (b. 1920). Burin has constructed four spaces that compose an immersive environment, each staging a curated selection of photographs, architectural drawings, texts, and design objects, a combination of historical and newly recreated material loosely inspired by Hosken’s work. Extracting relevant characteristics of the designer’s history, Burin’s material landscape brings Hosken’s aesthetic ambitions to life.

In 1944, Hosken was among the first women to receive a master’s degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). In 1951, she established a design business, Hosken Inc., which produced jewelry and furniture. Hosken attempted to collaborate with modernist greats, such as Walter Gropius, but her various efforts failed, and in 1963 she closed her company and sued GSD for sexual discrimination, a decision that foreshadowed her later work as a female rights activist.

Through the staging of exhibitions of real and imagined material, Burin assumes the roles of archivist, artist, and designer, as in her 2012 exhibition at Ratio 3, “Andrejova-Molnár Papers,” a project dedicated to …

July 19, 2013 – Review

"Transmissions"

Tara McDowell

“Transmissions” is the second of two back-to-back group shows at Altman Siegel. Gallery manager McIntyre Parker curated the first, which he titled after a line in a poem by Matthea Harvey: “O the sleeping bag contains the body but not the dreaming head.” In contrast to such titular loquaciousness, the show was an exercise in restraint. (Restraint also defines Pied-à-terre, Parker’s gemlike house gallery out towards the ocean, which often shows a single work by an artist in the basement garage.) Whole walls remained empty, and two of the three artists included (Aaron Flint Jamison and Anicka Yi) presented just one work apiece. Centered by Alice Channer’s draped floor-to-ceiling banner printed with a giant image of wet hair and Pantene shampoo and conditioner, the show felt unexpected, charged, and destabilizing. Destabilizing spatially, because of its utter precision, but also destabilizing—in the best way possible—any attempts at coming to grips with what this work values and what these young artists want.

By contrast, “Transmissions” is far tidier, and its art historical references are worn more readily on its sleeve. This second and current summer group show is both more conventional and yet more solid than its predecessor. It feels more familiar, too, …

November 29, 2012 – Review

Miriam Böhm’s “Before in Front”

Tara McDowell

Stepping into Ratio 3’s new space on Mission Street in San Francisco and encountering Miriam Böhm’s austere photographs involves no small amount of perceptual and cultural reorientation. On Mission Street, inner-city kids, leftist bohemians, young hipsters, and day laborers move through a stretch of San Francisco populated by taquerías, Chinese take-out joints, discount stores, beauty salons, panaderías, Latino groceries, and high-end bistros. The gallery’s former life was as Darlene’s Fabrics, sandwiched between a Foot Locker and a Money Mart; now the entire storefront has been painted matte black, including windows and doors. Minimal gallery signage in subdued white lettering gives no indication for whom or what this space, so alien to the visual cacophony of the street, might be. The interior’s poured concrete floors, bright florescent lighting, and severely angled, off-kilter white cube architecture are unusual for San Francisco, though less so for Chelsea or Berlin.

Böhm has installed her photographs with sensitivity to this architecture, which is why I draw attention to it here. On view are five sets of photographs, each hung as a discrete grouping in a straight line. The hang, however, responds to the architecture in quirky ways: Böhm placed the first photograph in the series Reference …

Load more