Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

June 4, 2019 – Review

Peter Friedl’s “Teatro”

Raimar Stange

Puppet theater is something you don’t see often in an art exhibition, and here the characters are four historical figures who were important in times of transition in diverse ways: John Chavafambria, known as the “Black Hamlet” of psychoanalysis; Henry Ford, founder of Ford Motor Company; violinist Julia Schucht, the wife of Antonio Gramsci; and Toussaint Louverture, leader of the Haitian revolution of 1791–1804. Rooted in disparate places and times, the protagonists of Peter Friedl’s puppet show The Dramatist (Black Hamlet, Crazy Henry, Giulia, Toussaint) (2013) enact potential performances of counterfactual historical narratives. These productions do not follow such conventions as the description of a linear sequence of events, accepted historical research or its usual forms of representation—they remain in the realm of the possible. Concurrently denied, the puppets hanging there lifelessly await their use even though their strings are hung so high that playing them would be impossible.

Change of scene: the video installation Report (2016) stands at the center of “Teatro,” this remarkable, critical exhibition which dissects hegemonic forms of thought. The work, previously shown at Documenta 14 (2017), initially shows the stage of the National Theatre of Greece in Athens, empty, with no stage design and hardly any …

December 18, 2018 – Review

Donna Huanca’s “Piedra Quemada”

Rose-Anne Gush

Flatness, surface, posture, and the notion of cycles animate Donna Huanca’s “Piedra Quemada” [Scorched Stone]. The exhibition, displayed across Vienna’s Lower Belvedere museum, is a Gesamtkunstwerk consisting of 33 works including paintings, mixed-media sculptures, and live models whose bodies, painted by the artist with bright colors, move slowly throughout the space. In the first room, blue, green, white, and pink oil and acrylic paints billow across ten canvases. The paintings’ titles (all works 2018) point to forms of containment, growth, process, and sedimentation, as in MOULD, CYANOBACTERIA (bacteria which gain energy through photosynthesis), and ACRITARCH (an organic microfossil believed to be up to 1400 million years old).

In the center of the room is a platform covered in a layer of almost invisible white powder, which carries traces of foot and body prints made by Huanca’s models. Displayed on the platform is the steel frame of PARA ELYSIA (MARIPOSA) [For Elysia (butterfly)], one of the five mixed media sculptures presented in the show. Stretched and pulled around the skeletal structure whose shape evokes a head and torso are scrunched plastics painted with opalescent oils and acrylics. A rope made from synthetic black hair further anthropomorphizes the work. In the multi-screen video …

September 27, 2018 – Review

The Current II Expedition #1: “Spheric Oceans”

Chus Martínez

Expedition: “Spheric Oceans” led by Chus Martínez Participants: Julieta Aranda, Claudia Comte, Francesca von Habsburg, Eduardo Navarro, Ingo Niermann, Markus Reymann, Teresa Solar, Albert Serra

I decided to name this three-year cycle on artistic intelligence, philosophy, science, and nature the Spheric Ocean. The Ocean is spherical because it is not beside the earth nor below it, but all around it. Its form is not what our eyes see, or not only. Its reality cannot be separated nor told apart from anything else on the lived earth. Therefore it poses us a demand: the need for a philosophy to help us exercise the Ocean. It is difficult to describe what we are aiming for. I would say we are aiming for a philosophy more than anything else. It would be wrong to think that when we say “Ocean,” we are naming a “subject.” We could be as radical as stating that today, to say “Ocean” is to say “art.” Art without the burden of institutional life, without the ideological twists of cultural politics, art as a practice that belongs and should belong to the artists, art facing the urgency of socializing with all those who care about life. Or, in other words, …

May 24, 2018 – Review

Haim Steinbach’s “Mojave”

Max L. Feldman

“Mojave” is the name of the rectangular desert-yellow color furthest to the left in Haim Steinbach’s mural eswürdesoaussehen [itwouldlooklikethis] (2018). Painted on the back wall of the gallery, this 13-color dissection of an Ellsworth Kelly painting is individuated by English translations of the Austrian names of wall paint hues (Hitradio is “Loyal Blue,” Zwetschenfleck becomes “Plum cake”) written underneath the colored squares in their manufacturers’ branded typefaces. Placed at the back of the exhibition, it is both typical of Steinbach’s non-hierarchical organization of objects in the space and of his strategy of transferring commercial materials to the walls.

Three other mural works on view—the yellow Pantone color of pantone7549c (2018), playboy of the west indies (2018), and the lion king (2018)—reflect Steinbach’s long interest in brands and consumer products, as well as his 30-year battle with Marxist critics’ dismissive use of the term “commodity art” in relation to the “extreme ambivalence” of his practice, described variously as emulating “the narcotic rhythms of the marketplace”, or being “not unlike flower arranging.” Steinbach rejects Marxist concepts like commodification and labor, but his activities—evaluating, choosing, buying, arranging, and displaying items—are just like those of the consumer. For Marx, alienated labor immiserates individuals by distorting …

April 18, 2018 – Review

Sebastian Jefford’s “Procrustean Flatulence”

Kimberly Bradley

Procrustean—what does the word even mean? In Greek mythology, Procrustes was the son of Poseidon, and a thief who tortured his victims by making them lie on an iron bed. If their bodies were too long, he’d cut off the oversized bits; too short, he’d stretch their limbs to fit. Both procedures were fatal, and, Goldilocks-style, few victims fit the bed. “Procrustean bed,” the idiomatic phrase in which the word is most often used, denotes an arbitrary and brutal standard.

Yet conformity—aesthetic, thematic, or otherwise—is not what a visitor gets from Welsh artist Sebastian Jefford’s exhibition in Gianni Manhattan, a skylit, subterranean space in Vienna’s third district, open since January 2017 and arguably the most daring and international of the city’s crop of new galleries. Hung on the wall beside the downward metal ramp leading into the gallery is Aggressively Indeterminate Biscuit (all works 2018). It’s arresting enough to make me stop.

The core of the sculpture appears to be a flattened cardboard box, overlaid at its edges with thick, bulbous protrusions clad in patchworked sheets of gray polyurethane foam, their surfaces indented with what appear to be shoeprints and studded with the colorful, plastic snap-fasteners found on jaunty sportswear. On the …

February 27, 2018 – Review

Július Koller’s “Subjektobjekt”

Max L. Feldman

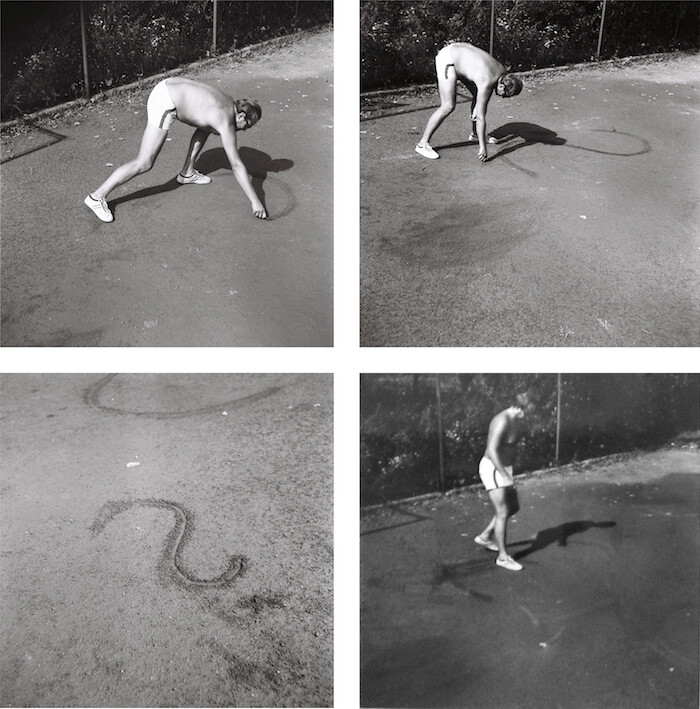

Július Koller’s “anti-happenings” are reflexive practices, acting out a lived situation—relating mostly to Czechoslovakia’s repressive, post–Prague Spring “normalization” period between 1969 and 1987 and the limits of artistic activity at the time. Documenting silly or banal everyday activities, including ping-pong games, taking photographs of groups standing in a question mark (his signature symbol), or simply painting and teaching, Koller turns being together with others into Subjektobjekt, a position of personally and artistically transformative “subjective objectivity,” raising collective awareness of the relation between private life and the official public space monopolized by the regime.

The key anti-happening in the exhibition, which stretches across three floors and still displays only a tiny fraction of Koller’s vast output, is the black-and-white photographic grid Question Mark 1-4 (1969). Showing a shirtless Koller etching a question mark into the clay of a tennis court with his finger, we see two themes converge: for Koller, tennis is a non-artistic activity requiring fair play and obedience to the game’s predetermined rules, while the question mark symbolizes free, democratic communication. This anti-happening then becomes a quietly anti-authoritarian demonstration of the value of intersubjective know-how, granting others—friends, tennis partners, fellow citizens—the same status we would have them grant us.

The anti-paintings …

November 28, 2017 – Feature

Vienna Roundup

Orit Gat

Walking home at night, I pass by Campaign (1972), a two-channel video installation by Ferdinand Kriwet projected onto the storefront windows of Georg Kargl Fine Arts. In the dark street, the images of television footage from the 1972 US presidential campaign fronting Richard Nixon and George McGovern are silent; at the gallery during the day, they almost disappear against the light, but the field recordings, collected by the artist on a trip to the US to witness the primaries, are audible.

The sound of talking heads and debates shapes the experience of the exhibition, a last remnant still on view from curated by_Vienna, a festival inviting international curators to organize fall exhibitions in the city’s galleries. The theme of this year’s iteration was language in contemporary art, and curator Gregor Jansen honed in on the 75-year-old German artist’s longstanding interest in media and focus on text and dissemination. These are crucial issues in our divided societies, in which it is inconceivable that any candidate could win a landslide like Nixon’s (who won 62 per cent of the vote, taking every state except Massachusetts and Washington DC). Jansen did not need to spell out a connection to contemporary politics: speech and its …

November 7, 2017 – Review

Ferdinand Kriwet’s “KRIWET”

Kimberly Bradley

Whirlpools of words, sans-serif swirls: language is both subject and material of Ferdinand Kriwet’s exhibition at Georg Kargl Fine Arts, part of this year’s curated by_Vienna. In some of Kriwet’s text-based works, the typographical forms take clear precedence over linguistic sense; in others, the words’ meaning packs the stronger punch.

“KRIWET” explores the multidisciplinary, multipronged, and until recently underexposed oeuvre of German artist Ferdinand Kriwet, whose practice began in the early 1960s. Back then, at the age of 19, he produced his first “Hörtexte” [aural texts]; proto-podcasts in which meaning was obscured, the sounds and phonemes creating a sonic collage. Over the following decades Kriwet would return to expanded notions of collage and experiment with words-as-visual-material in mediums as varied as pencil on canvas, aluminum signage, wallpaper, even a series of oversize artist’s books.

Curated by Gregor Jansen, director of Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, this exhibition is essentially a mini-retrospective whose choreography immerses the viewer in the artist’s practice. Viewers are drawn in from the street by Campaign (1972–73/2005), an image-sound collage projected outward through the gallery windows, which here act as giant television screens. Kriwet collages black-and-white TV footage of Richard Nixon and George McGovern’s 1972 US presidential campaigns with broadcast news and …

September 14, 2015 – Review

"Tomorrow Today"

Pieternel Vermoortel

On my way to curated by_vienna, a Grand Tour of the city’s galleries timed to coincide with the Vienna Biennale, I pass by the city’s sleek new Hauptbahnhof. Migrants from Syria and Afghanistan come together here after having traveled along what the media call the “Eastern Land route” and “Western Balkan route.” They will not be staying here, but are in transit, on the way to Germany. I talk to a volunteer: today clothes are not needed, but they are short of sleeping bags, shampoo, and diapers. Philosopher Armen Avenessian’s text—from which “Tomorrow Today” takes its name—begins with an insight that he attributes to J.G. Ballard: “Today, science fiction might be the best kind of realism—if, that is, it is not the only possible realism.” What is needed today, we—as citizens—try to provide. We, as a community, play a role in catering for the basic needs of existence. We cannot turn the clock back to alter the situation as it is, but we can try to meet the needs that could have been expected to come, a future predicted by some. “Tomorrow Today,” the title for this year’s curated by_vienna, serves as the impetus for Avanessian to look at our …

January 13, 2015 – Review

Manfred Pernice’s “dosen,cassetten,Zeugs”

Chris Sharp

What exactly a Scottish bagpipe player was doing performing at a Manfred Pernice opening was not immediately clear to me, nor perhaps to anyone else who was there. And yet, seeing the musician periodically march out and solemnly blow into and kneed his large, bladder-shaped bag among a group of Pernice sculptures somehow made perfect, if oblique, sense. But why? Perhaps it had something to do with Pernice’s marginalization of cultural specificity, and the retiring and essentially atmospheric nature of his work. Indeed, for his fifth show at this venerable Viennese apartment gallery, the German sculptor seemed to want to create a semi-depressed club-like setting, as if his work were not actually the main event, but the delightfully dismal backdrop to it. As such, the works carried out a specious flattening that dallied with—but humbly declined—to be flattened.

In the main space, which was sparsely outfitted with several large MDF cylinders painted or covered with fabric evocative of, say, standing bar tables and trashcans, the works seemed to assume the position of backdrop. Brightly painted, smaller, stool-sized versions of the cylinders could be found in corners, while in another angle lurked the bleakest and most captivating Christmas tree I’ve ever seen. …

December 11, 2013 – Review

Andy Boot

Aaron Bogart

Looking up into the night sky, you wouldn’t think that the color of the universe is beige, or “cosmic latte,” as a group of scientists from Johns Hopkins University has dubbed it. But then again, looking at Andy Boot’s new sculptural installation, you wouldn’t think that the exhibition has anything to do with the internet. After all, the seven sculptures made from simple, low-tech materials, like fiberboard, appear as if they have been cut from a graphic design book and randomly nailed together, revealing nothing of the complex digital process which gave them life.

The walls of the gallery up to the ceiling have been painted cosmic latte, a hue astronomers “discovered” by averaging all the light emanating from the stars of various galaxies, which also serves as the show’s unofficial title. This color was an incidental byproduct of studying star formation; its official name was created randomly, when one of the scientists stared deep into his coffee in Starbucks. Taking the silliness of this scientific discovery as his starting point, Boot randomly chose images from the internet and used Photoshop to excise all the colors except cosmic latte, leaving only creamy colored shapes. He then zoomed in on computer generated …

October 11, 2013 – Review

VIENNAFAIR and Highlights from curated by_vienna 2013

Astrid Mania

When musician David Byrne manically repeats the line “same as it ever was,” it fails to bring pleasant thoughts to mind. To say these same words about this year’s VIENNAFAIR, however, is to acknowledge the value in returning to a pre-existing order. Last year, the fair was a strange hybrid of the VIENNAFAIR and Art Moscow; with a keen interest in boosting revenue, Russian investor Sergey Skatershikov had hurriedly appointed two new artistic directors for the 2012 edition, one of whom also helmed Art Moscow. But now the annual showcase is back in form, and again under new ownership—Skatershikov’s former partner and real estate developer Dmitry Aksenov is now in charge. The familiar combination of Viennese establishment and lesser-known Eastern and Central European figures has returned, along with a mixed bag of all sorts.

Despite these recent changes in direction, VIENNAFAIR is still primarily a European affair. Among the 127 participants, only one and a half exhibitors are from the United States: Marc Jancou Contemporary from New York/Geneva and debutant Steve Turner Contemporary from Los Angeles, who paired Maria Anwander’s erased art magazines with Pablo Rasgado’s assemblages of painted drywall. The only East Asian participant is South Korea’s Gallery H.A.N., with …

July 16, 2013 – Review

"is my territory."

Kimberly Bradley

Not long into a recent visit to Christine König Galerie in Vienna, I was overcome with anxiety. Faced with a lot of work by artists I’d never heard of, I felt a familiar, acute need for a press release to explain the clipped and cryptic “is my territory.,” the group show curated by a Berlin-based artist who teaches, nonetheless, in Vienna: Monica Bonvicini.

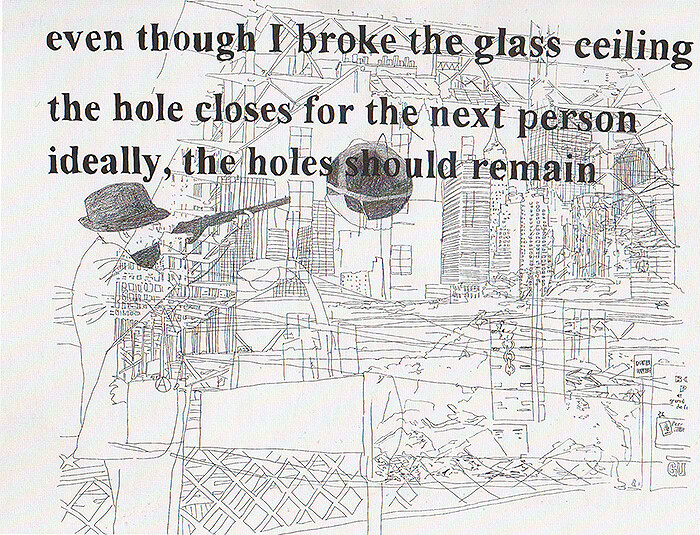

Attributed to a long list of seemingly unrelated writers (Johannes Porsch, Reinhard Priessnitz, Georges Perec, Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, and Bonvicini), the abstract text—“‘I’ stayed a while. ‘I’ left and came back later”—only worsened my angst. But near the desk was clearly the exhibition’s centerpiece: a work by Bonvicini with Sam Durant, with whom she collaborated on her seminal “Break It / Fix It” exhibition in the Secession in 2003. Hole (2003) is a poster-like drawing depicting a man training a rifle at a large black hole in an outlined city landscape, over which a text proclaims: “even though I broke the glass ceiling the hole closes for the next person. ideally, the hole should remain.”

This, one expects, encapsulates what this exhibition is about—or maybe not: before it goes fully abstract, the text states that the show “represents …

May 17, 2013 – Review

“U.F.O.-NAUT JK (Július Koller) orchestrated by Rirkrit Tiravanija”

Simon Rees

Anyone who grew up in the 1970s and watched the Children’s Television Network/PBS educational series Sesame Street was subliminally prepared for the gamut of conceptualism in (contemporary) art. No character prepared one better than the “Mad Painter,” who popped up in the unlikeliest of places in his Chaplinesque bowler hat and signature striped shirt to paint the “number of the day” on an unsuspecting surface or person: bald or balding pates were regularly and hilariously victimized. They always realized their fate all-too-late and then chased the Mad Painter out of the frame, oftentimes with the reel sped up to look like the Keystone Cops, or, again Chaplin, to the accompaniment of a vaudevillian or ragtime/honky-tonk piano. While Július Koller (1939–2007) was making his “U.F.O.-NAUT” works long before the Mad Painter ever went on air, whether Rirkrit Tiravanija’s channeling of Koller performs a double-entendre of channeling the Mad Painter is the question. Tiravanija, born in 1961, is certainly of an age and spent time growing up in Canada where Sesame Street was a television staple in the 1970s. This exhibition is essentially a re-presentation and re-framing of Koller’s “U.F.O-NAUT” works by Tiravanija—to claim a sympathetic conceptual predecessor.

The Mad Painter comes to …

January 31, 2013 – Review

Birgit Jürgenssen’s “Stoffarbeiten”

Kimberly Bradley

I thought it might be my imagination, but it seemed that every winter I happened to be in Vienna, Galerie Hubert Winter—a mod two-level space directly behind the MuseumsQuartier—was showing another exhibition by the late Austrian artist Birgit Jürgenssen, who was born in 1949. The name was the same, yet the work often varied dramatically from one show to the next. Last year, I stopped by to find out more. Yes, Jürgenssen has generally been featured in Winter’s first show annually since 2008, with each exhibition revealing one work series from the artist’s prolific output, produced (often simultaneously) throughout a career that ran from the early 1970s until her premature death at age 53 in 2003.

By now, the January slot is predictable, but it has been refreshing, sometimes astonishing, to observe Jürgenssen’s many approaches to her artistic practice (I often wonder, too, whether the artist herself would have approved of or objected to how these approaches are presented). A true multimedia artist well ahead of her time, Jürgenssen made drawings, cyanotypes, figurative and experimental photographs, text works, Polaroids, sculpture, abstract films projected onto her body, photorealism, and performance. What connects the work is a sense of womanness—beginning with the …

November 30, 2012 – Review

Sharon Lockhart & Noa Eshkol

Judith Vrancken

Four women stand in a light-flooded room, barefoot and dressed in simple black. The youngest is in her early thirties, the oldest in her early seventies. A metronome is turned on to an eager 120 beats per minute. One of the dancers counts in Hebrew softly, “Achat, shtaim, shalosh, arba,” as they start moving in perfect synchronicity and balance. One wrong move and they all stop and start over. The metronome never stops ticking.

Located in Vienna’s second district, and in the oldest Baroque gardens in the city, a spacious four-room exhibition space with sloping north windows serves as Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary’s gussy new venue. Here, its second show is dedicated to Sharon Lockhart (born 1964) who, in turn, made her subject the vast legacy of work left behind by Israeli dance composer Noa Eshkol (1924–2007). A few months after Eshkol’s death, during a trip to Israel in 2008, Lockhart stumbled upon a time capsule of work that the dancer left in Holon, a suburb of Tel Aviv. From the mid-1950s until her death in 2007, this was the place where she created and practiced the Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation system (EWMN) together with architect Avraham Wachman (1931–2010). As a former student …

October 1, 2012 – Review

Highlights from “curated_by, Vienna”

Kimberly Bradley

Everything feels hyper-politicized right now. This is true in the real world, of course … and, increasingly, in the art world. Lately, at least in Central Europe, fake (or “fake”?) Occupy camps are cropping up at nearly every major contemporary art event. The recent Berlin Biennale’s camp-as-university is probably the most notorious example, but there was also the ragtag tent encampment in front of the Fridericianum at Documenta 13. Even at last week’s ViennaFair (September 20–23, 2012), a rotating group of artist-activists blogged, DJed, and performed in an enclosed area at the edge of the exhibition hall, irritating gallerists with booths nearby with their raucousness.

Sigh. Considering this often contrived, too-obvious appropriation of “politics” makes this year’s “curated by” in Vienna all the more refreshing. “Kunst or Leben: Ästhetik und Biopolitik (Art or Life: Aesthetics and Biopolitics)” is the overriding theme of a citywide event generously funded by the city of Vienna’s creative agency, Departure, since 2009. (Amazing but true: some cities have agencies to financially support creative endeavors and industries—residents of those without can keep dreaming). We can thank curator Eva Maria Stadler for adding the “bio” to the “politics”: this edition of “curated by” is meant to re-address—through the …

April 19, 2012 – Review

Ricardo Brey / Jimmie Durham’s "looking at my own work (and his)"

Max Henry

An artist’s best consigliere is often another artist, a partner in crime who follows the adventurous path of an undefined yet malleable future. Chance encounters often lead to influential long-lasting relationships. Youthful firebrands grow canny to become wizard practitioners of subversive unorthodoxies. Such is the case in “looking at my own work (and his),” a joint exhibition of two long-time friends of thirty-plus years, Ricardo Brey and Jimmie Durham.

With wily self-control and daft humor these two shamans have produced a bricolage of objects that underscore the exhibition’s premise that is more of a dialogue than a collaboration. That is, one artist observing another, responding in kind to unconventional thinking. Apropos of the Freudian city, Brey and Durham have produced a bracing repartee of predominantly sculptural works.

Along with numerous iconic sculptural pieces from the early 2000s to 2011, Brey shows a few two-dimensional works from 2003. They’re part of a series on flight that are a continuation of his cosmological compendium of a thousand drawings that became a hefty 500-page tome called Universe. From bees, to bugs, to birds, the yellowish hue of the mixed media on rice paper are made to appear as archival specimens that German naturalist Alexander von …

November 1, 2011 – Review

Nader Ahriman’s "Die Hegelmaschine trifft die Weltseele"

Max Henry

Looking at Nader Ahriman’s paintings is somewhat analogous to reading Wittgenstein’s Tractatus or Pound’s Cantos; you need a guidebook to navigate the arcane references and codes. Nonetheless, his artistic gravitas grabs you immediately, pulling you into his very own dialectic apparatus. Mythological man-machine hybrids abound in theatrical mise en scènes hovering amidst geometric platforms, textual markers, and free-form associations.

Since the mid-1990s, Ahriman has consistently mined the grey areas of sociopolitical history, philosophical inquiry, and critical reasoning. A philosopher trapped in a painter’s body, Persian-born Ahriman exiled himself to Germany in the 1980s. As an outsider in a foreign land, he took solace in the traditions of 19th-century metaphysical philosophy of his adopted country.

For this sublime show very in line with the Viennese psyche, “Die Hegelmaschine trifft die Weltseele” (The Hegel Machine Meets the Soul of the World), Ahriman presents works created over the past seven years: watercolors, mixed-media collages, a series of inter-related paintings, and a single but important wall-mounted sculpture. The crux of the show is a new series of mixed-media drawings depicting Hegel’s 1806 encounter with Napoleon Bonaparte on horseback riding to a reconnaissance mission in Jena, a university town in central Germany that the French had occupied. …

May 31, 2011 – Review

curated by_vienna 2011

Max Henry

Eastern European melancholia has a residual effect in the post-Communist era. To the Western capitalist-bred outsider, it’s a palpable element in a contemporary artistic milieu that grapples with traumatic memories. Take a stroll though the Vienna flea market—with its leftover household porcelain bric-a-brac, faded Stalinist era postcards, and propagandistic souvenir trinkets—and you’ll know what I mean.

Vienna has a particularly strong contextual and historical insight into the psyche of its Easterly inhabitants. Paid for by the hefty purse of the municipal cultural arm of the city, the initiative called “curated by_vienna” invited local galleries to organize shows by independent and institutional curators. Their mandated framework on Eastern European integration “East by Southwest” offered such specialist curators a discursive platform. (Turkey was included as a historical pivot point between east and Occident and its on-going flirtation with joining the union.)

In the few shows I saw, leitmotifs abounded: folk legend and superstition, historical marginalization, religious and cultural identity, borders and mapping, linguistic differences, research-based works, and postcolonial discourse were threaded together in the alienated Pop vernacular of 2011.

At Kerstin Engholm, Adam Budak delivered a tightly focused project on the Trans-Caucasus and Eurasia. This has particular resonance today due to the oil pipelines running …

April 20, 2011 – Review

Bernadette Corporation’s "Stone Soup" at Galerie Meyer Kainer, Vienna

Max Henry

“The image is one thing the man is another, sure I’m a shy country boy,” Elvis Presley once quipped at a press conference before standing up grinning to reveal a glittering diamond studded belt buckle to a fawning media assemblage. Before there was bling there was the King, and the cultish glamour industry he propelled.

When entering the soaring space of Galerie Meyer Kainer to view Bernadette Corporation’s (BC) “Stone Soup” one encounters a monolithic fashion ‘advertisement’ in the style of Calvin Klein or Bulgari. It’s the set piece for a pseudo ad campaign for a real luxury jeweler (Judith Ripka) shot for BC by photographer Alex Antitch. Equal parts totemic minimalist jibe and talismanic icon, the crumply John McCracken style obelisk towers nearly four meters high in the gallery. Wrapped and bound by rope around metal scaffolding, a photo image of a nubile model is printed on its glossy billboard vinyl, her vacant face bejeweled with oval shaped diamond earrings.

In the long rectangular main gallery are a series of framed inkjet and c-prints, stock model calling cards and prints mounted on aluminum that have the sleek stretch limo glamour of a fashion editorial. Some of these professionally retouched photos hang …

Load more