Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

April 4, 2024 – Feature

Cynthia Carr’s Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar

McKenzie Wark

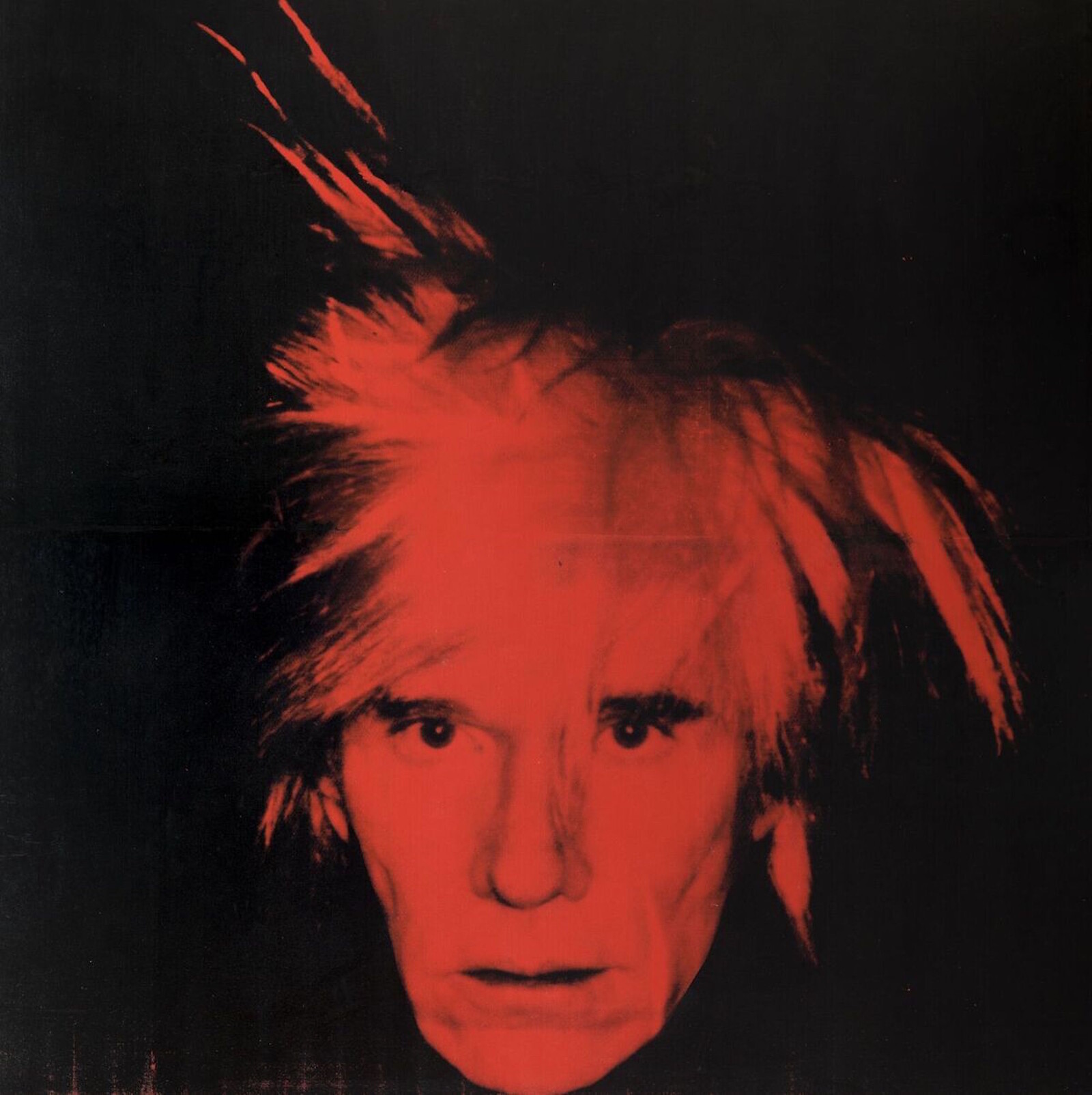

I probably speak for many trans readers of Cynthia Carr’s biography of Candy Darling when I say that I have very mixed emotions about it. On the one hand, I’m grateful for Carr’s tireless work in documenting the life of Andy Warhol’s most luminous trans superstar. On the other hand, it’s painful to read page after page of people who hated Candy, abused her, insulted her, exploited her, or, on a good day, merely disrespected her.

Born in 1944, Candy grew up on Long Island. Her father was an asshole. Her mother, at best, put up with her. She was one of those whom straight people, cis people, perceives as other from the start. High school was a torment. As a young Candy confided to her diary: “Nobody loves or understands me. This is a wicked world, I think.” She was right.

The wicked world was out to crush her long before she could fashion herself as “Candy Darling.” Around 1962 she started taking the Long Island Railroad into Manhattan to escape, mostly to hang out around Washington Square. She started constructing a persona through which to survive: “I must learn to charm people in a quiet way.”

Carr does …

March 25, 2024 – Feature

Multi-Sensory Languages: On Colomboscope 2024

Elena Sorokina

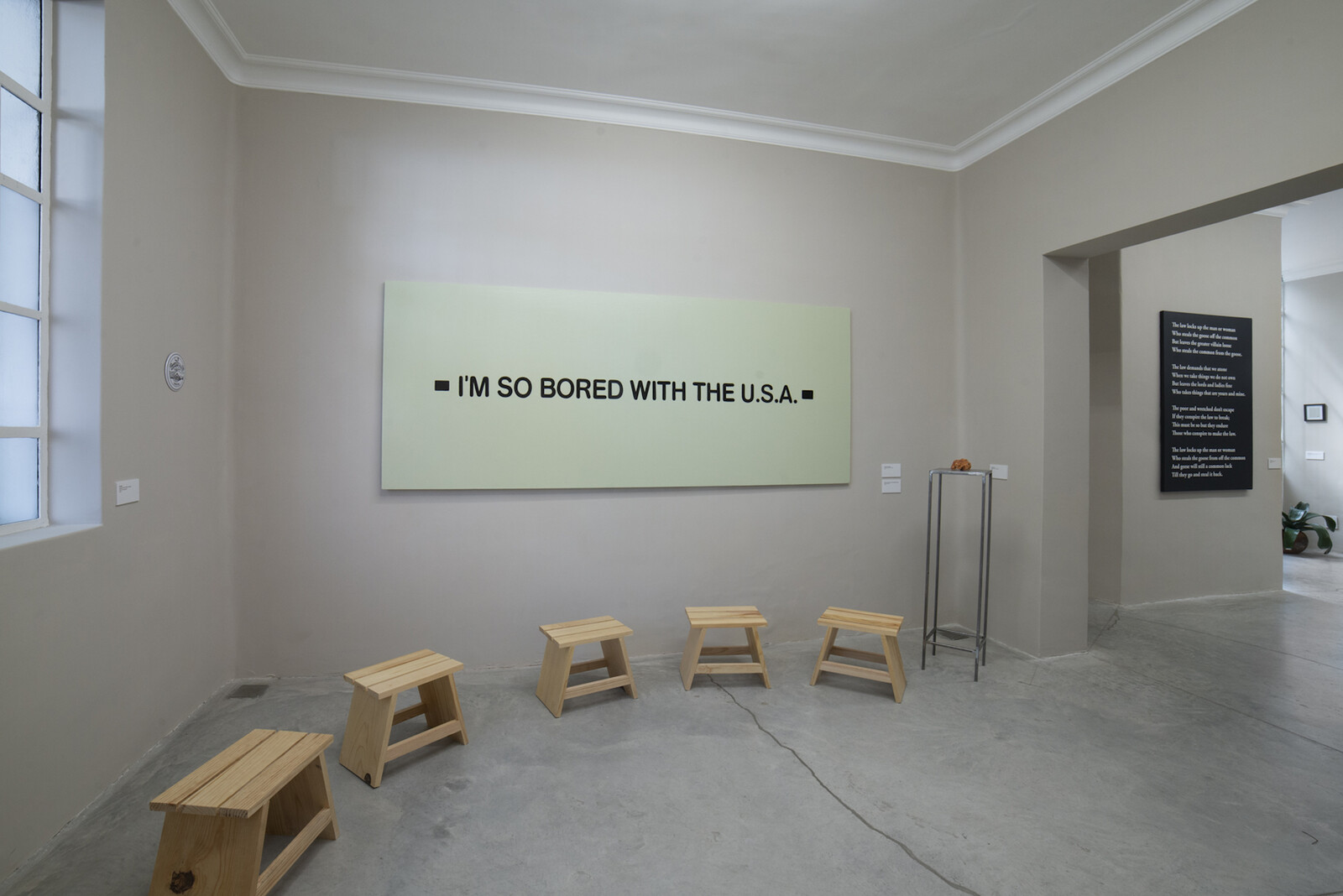

“The endless symbolism of forests lies in their low visibility,” writes Anna Arabindan-Kesson, “to move through the dense entanglements of these spaces we need all our senses.” The same might be said of Colomboscope, Sri Lanka’s interdisciplinary arts festival now in its eighth edition. Dense, multi-sensory, and rhizomatic, it speaks through entanglements and intersections, and flows beyond exhibition spaces to wetland walks, conversations with forest gods, and other “mushroomings.”

At JDA Perera Gallery, the main exhibition space, the architecture of meaning can be perceived like a forest stratification, combining a layered verticality with dense horizontal interconnections. Suspended between the gallery’s floors, Ecophora (2023), a light installation conceived by Pankaja Withanachchi and Roshan de Selfa, connects the layers, and calls attention to our precarious relationship with visibility. Deep in the forest, only a flickering vision is possible for the human eye, which occurs when sunlight shines through trees. This phenomenon—called Komorebi in Japanese—is recalled in the artwork’s evocation of the moving luminosity of the forest, inviting the viewers to activate all their sensors.

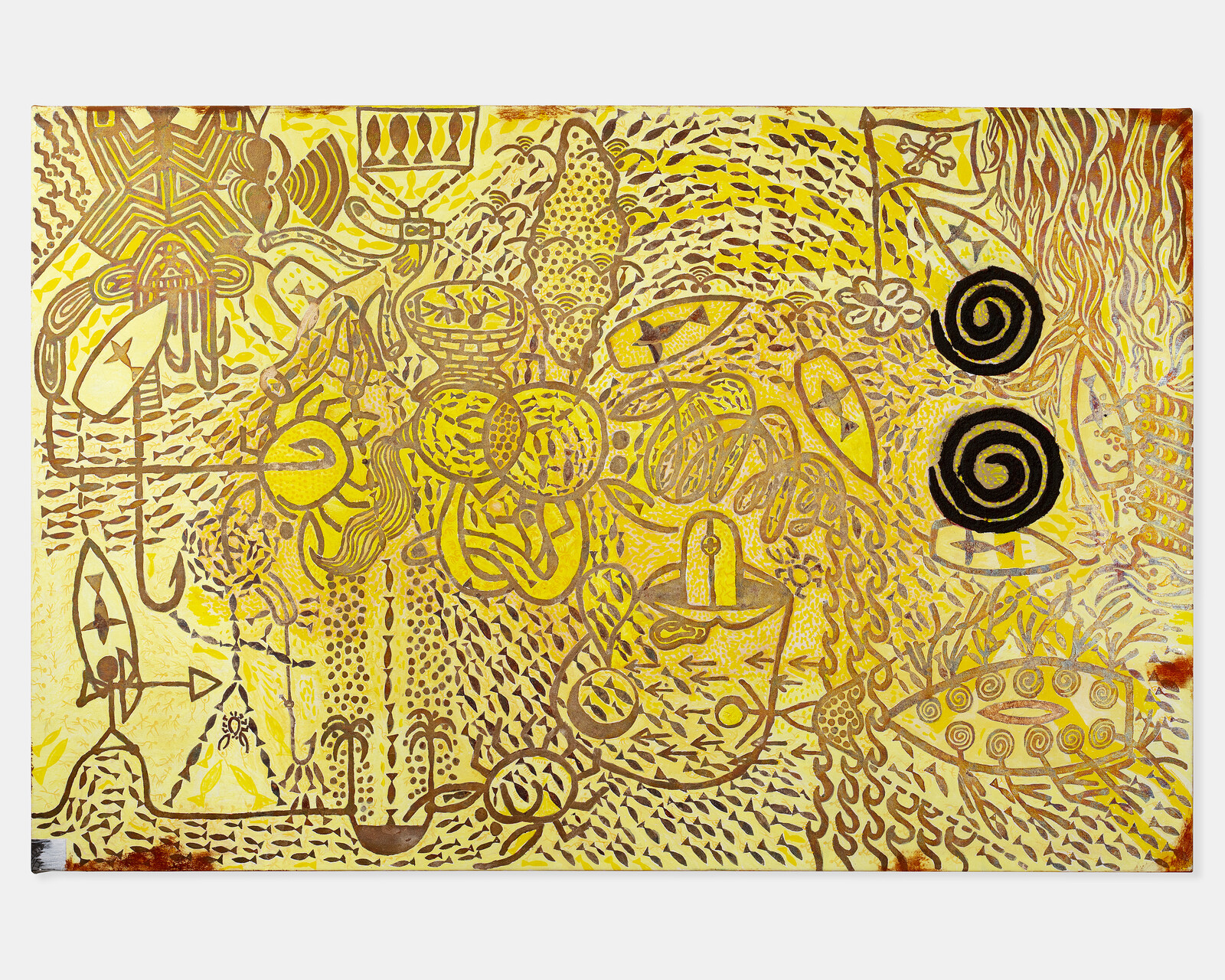

Ecophora’s shadows almost reach the Ceylon currency made by Laki Senanayake (1937-2021). One of a wave of post-independence artists in Sri Lanka whose work crossed disciplinary boundaries, Laki’s …

February 1, 2024 – Feature

“Condo London”

Orit Gat

“I’ll be honest, I was a little shocked to recall the plate of bratwurst and mash that I tucked into three days after my husband died,” writes Kat Lister in The Elements. She goes on to describe Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut’s “Dual Process Model” of bereavement—the way mourners shift between loss and reparation, a fluctuation of feelings in the face of tragedy. As Lister writes, things happen at the same time—grief, pain, bratwurst, mash. The audaciousness of living on. How to hold all these things at once: to be in London looking at a collaborative project where twenty-three galleries allocate their spaces to their international counterparts or stage shared exhibitions that bring together works of wildly disparate forms. To talk about hosting when homes are being ruined.

This uneasy simultaneity is visible throughout Condo. At Warsaw gallery Import Export, hosted by Rodeo, the artworks on view discuss war, heartbreak, and climate catastrophe all at once. Just to the left of the entrance is horses [konie] (2023), a large acrylic and ink on canvas by Ukrainian artist Veronika Hapchenko. Based on mosaics from Pripyat, a town that serviced and housed workers at the Chernobyl Power Plant, it’s a grayscale work …

January 10, 2024 – Feature

What is Wrong with Us?

R.H. Lossin

Even during the best of times—a category for which the present certainly does not qualify—writing about art requires a certain suspension of disbelief. Simply engaging in criticism implies a vague normative claim about the social or political importance of elaborate and often expensive objects. It is a role that can be hard to defend even, or perhaps especially, when the objects claim a political position. But since looking cannot be separated from thinking, Josh Kline’s recent retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art (and its exuberant critical reception) merits some extra attention. Not because of the show’s “inscrutable lucidity,” or because the work’s position “between irony and sincerity” offers meaningful insight into the “propaganda it evokes.”

The reason is far too simple to require such attempts to extract complexity from proximal antonyms. Americans spend enormous amounts of time consuming mediated violence, so when images of cut-up human bodies show up in a major art museum, we should pause and consider what exactly we are thinking as we look at the severed head of a waitress on a tray. Kline’s show was widely reviewed (the New York Times published two pieces about it, Artforum gave it the cover), and yet …

December 1, 2023 – Feature

Robert Glück’s About Ed

John Douglas Millar

How to convey the power of this book? The achievement of its language is such that it resists easy translation into criticism as practiced in any conventional mode. Narratively it recounts Glück’s life with the artist Ed Aulerich-Sugai in the 1970s, and the time he has lived since Ed’s death from AIDS in 1994. It is organized concentrically so that the death takes place at the precise center of the book, where there is an extraordinary description of the performing of a last rite, the washing of Ed’s corpse by Glück and Daniel, Ed’s final lover: “We hurry as though Ed might be impatient. Here is the dusky skin, here the straight back, the slightly bowed legs, the narrow waist, the flat ass. AIDS has restored the body I lived with long ago, so thin that I watched his heart beating against his chest till my senses bled in marvelling tenderness.” And right at the center of this description there is a single drop of blood: “Daniel pulls down Ed’s underwear and milks one bright red drop from Ed’s cock. The drop of blood is the only indication of the pandemonium that occurred within this body … Ed’s murderous blood.” …

October 25, 2023 – Feature

Mexico City Roundup

Gaby Cepeda

Mexico City’s cycle of exhibitions often feels like a hamster wheel that never stops turning. This fall’s openings, however, set a more introspective and meditative—and perhaps not as obviously market-driven—pace. Yes, there was a lot of painting. But much of it felt quite unexpected in its deviation from recent attachments to the colorful and the figurative, and notably more mature than the pop-culture fixations that have crowded the city’s galleries of late. This approach to painting could even be broadly described as a form of disengagement or retreat: a movement inwards, embracing dreams and memories.

One such example was José Eduardo Barajas’s “Saliva,” his debut solo show at PEANA. Barajas’s practice to date has dabbled in post-internet aesthetics, creating loosely rendered CGI images of diamonds and currency falling from the sky. Earlier this year, however, for “Mnemósine” at Proyectos Multipropósito, Barajas replaced the ceiling tiles in a massive office space with tile-sized, loosely landscape paintings showing clouds, sunsets, dice, car rims, and hair (among other things) in reconfigurations of his earlier, CGI-oriented work. That show was a preparatory sketch, of sorts, for “Saliva.” In this tighter—and more impressive—body of work, Barajas magnified his experiments with landscape painting, and turned them …

October 20, 2023 – Feature

London Roundup

Chris Fite-Wassilak

“Celebrating 20 years,” ran the bus and magazine ads for Frieze London, keen to capitalize on having reached a milestone. In 2003, the first fair was welcomed as a galvanizing and creative force—a Studio International review from the time breathlessly described it as the “the real thing […] the apotheosis of swing […] the Stargate.” Such enthusiasm seems cute now, after the artist projects that supposedly set the fair apart from other trade events (Mike Nelson earning a Turner Prize nomination in part for his 2006 installation at the fair) have been scaled back almost to invisibility, and the “Focus” section for younger galleries, introduced in 2013, effectively assimilated parallel smaller fairs such as Zoo and Sunday. Of the 164 stand-holders at this year’s Frieze London, only 30 of them (predominantly, of course, the larger multi-venue galleries) were at the first 2003 fair. Through all this, the fair has long presented itself as an annual temporary institution, masquerading as such among the long-term underfunding of the city’s public museums.

This hoarding of resources has a distorting effect on coinciding and parallel events that would otherwise register as an alternative, both to the fair and other art spaces around London. Several …

October 19, 2023 – Feature

Contextures: Art and the Politics of Abstraction, Representation, and Identity (Part Two)

Andrew Stefan Weiner

This is the second installment in a two-part essay exploring the aesthetics and politics of the representation/abstraction dyad. For part one, which considered the history of New York’s Just Above Midtown gallery, among other spaces, curators, and artists who rejected received ideas about how abstraction and representation should operate, please click here.

Given the intense pressures facing many artists who identify and/or are marked as being in some sense “Other,” it isn’t hard to understand why the radical aesthetic and political world of spaces like Just Above Midtown might seem so compelling and so contemporary, despite nearly fifty years of historical distance. Figures like Linda Goode Bryant, Senga Nengudi, David Hammons, Howardena Pindell, and Randy Williams confronted something approaching a double bind, in which loyalty to an emergent Black nation seemingly meant sacrificing artistic complexity, and yet managed to repurpose this contradiction as a source of creative, critical dynamism. Over and against the long-facile valorization of abstraction or more recent dogmas surrounding representation, such artists instead grounded their practices in the rejection of false oppositions and in attempts to trace the imbrication of aesthetics and politics in the hybrid, conceptual-material forms that Bryant memorably framed as contextures.

That said, …

October 18, 2023 – Feature

Contextures: Art and the Politics of Abstraction, Representation, and Identity (Part One)

Andrew Stefan Weiner

This is the first installment in a two-part essay exploring the aesthetics and politics of the representation/abstraction dyad, with the second half to appear later this week.

In late 2022, The New York Review of Books published an essay entitled “Between Abstraction and Representation,” by the veteran art critic Jed Perl. Framed as a strangely nostalgic jeremiad, Perl’s text laments the decay of a once-robust opposition between abstraction and representation in visual art. Once, it claims, in the heyday of mid-century Manhattan, a tight-knit cadre of artists and critics agreed to fiercely disagree in a “war of ideas,” where artistic positions amounted to all-in personal, aesthetic, and political commitments; from this battle royale the strongest emerged victorious, thereby enabling a collective evolution of artistic forms. However, Perl argues, in subsequent decades the advent of new hybrid strategies and modes––a grouping loosely termed “postmodernism”––led art to become dangerously complacent and vacuous.

Citing a heterogeneous group of artists including Julie Mehretu, Gerhard Richter, and Simone Leigh, Perl claims that more recent efforts to recombine abstraction and representation have robbed these forms of their autonomy and authority, producing a “muddleheaded eclecticism.” Opposing this process of decline, Perl calls for a return to the …

September 29, 2023 – Feature

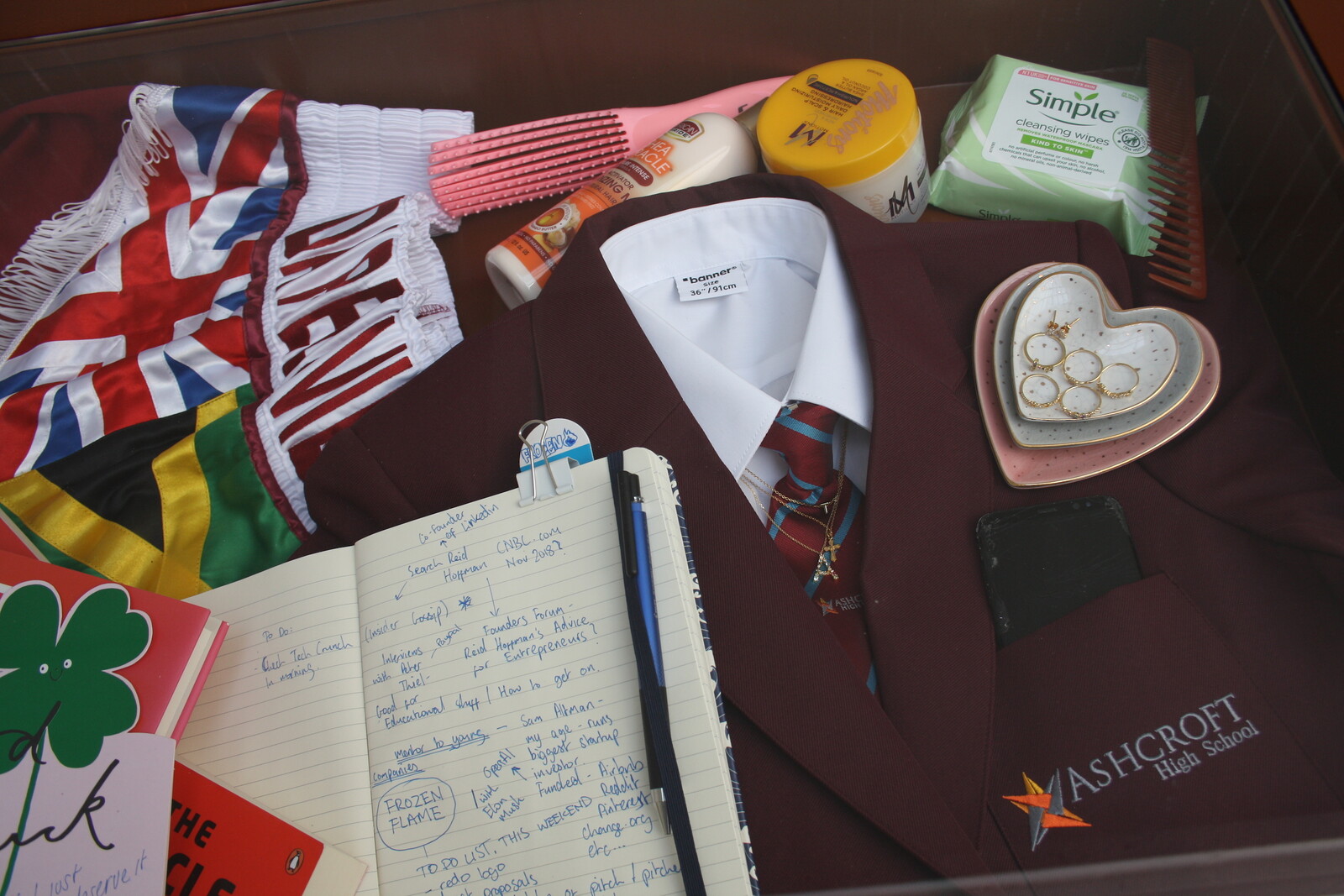

Valerie Werder’s Thieves

Wendy Vogel

In Valerie Werder’s debut novel Thieves, Valerie—an autofictional alter ego—chronicles her slide from disgruntled gallery copywriter to brazen shoplifter. At first she steals for the rebellious thrill of inhabiting other identities; eventually, and more abstractly, she steals to reclaim her time, words, and sense of self. Thieves centers on the New York blue-chip commercial art world, with its fussy idiosyncrasies and particular flavor of exploitation. But it is equally a novel about the fungibility of female identity—and a shrewd indictment of how language operates under capitalism.

Werder’s decision to write in a self-reflexive mode—a contemporary novel in the lineage of Semiotext(e)’s influential “Native Agents” series, edited by Chris Kraus and featuring authors such as Kathy Acker, Lynne Tillman, and Kraus herself—speaks to a desire to expose and explore the conditions under which Thieves was produced. Yet Werder is critical of how language is strategically deployed in the name of “authenticity,” both within the art world and literature. In Thieves, words bolster value, then drain themselves of meaning. People become expendable, while material things reinforce their self-worth. Over the course of the novel, Valerie becomes both a precious object and a voracious acquisitor. She enables, and is enabled by, a mysterious …

September 20, 2023 – Feature

Barcelona Gallery Weekend

Patrick Langley

Enric Farrés Duran’s show at Bombon Projects was among the most on-the-nose exhibitions at this year’s Barcelona Gallery Weekend (BGW)—and not just because of the glasses. That technologies that purport to measure the world are not reliably accurate is less troubling, his work proposes, than the tendency to act as if they are. These stark and satirical pieces reference optometry (pairs of dysfunctional glasses, such as one with two holes in its lenses, on freestanding plinths), museum display practices (a canvas turned to face the wall, another with nothing on it but a few tips for cleaning glass), and shooting (a wall papered with rifle targets). One work—a glass-fronted frame containing smashed museum glass—reduces the theme to the point of absurdity: not the “cracked looking glass” of Joycean modernism but an art that flaunts its own shattered illusions. The spectacles are broken, but they haven’t yet been replaced.

BGW’s ninth edition, which featured works by more than sixty artists exhibited in twenty-seven galleries across the city, showcased the robustness and vitality of Barcelona’s gallery scene. As such, it set an ironic context for a shared concern of several exhibitions: fragility. This manifested in the use of delicate materials—glass featured prominently …

July 31, 2023 – Feature

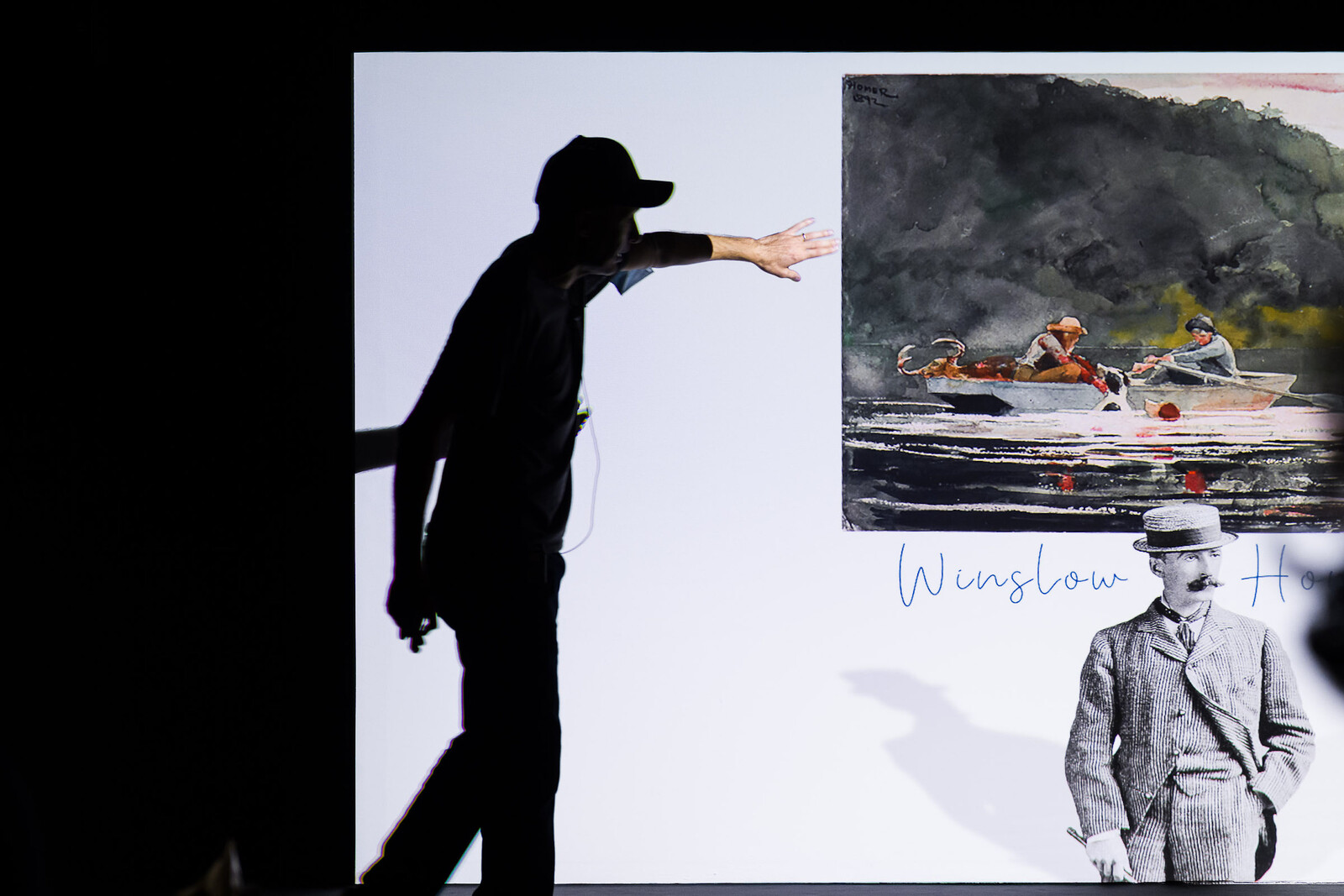

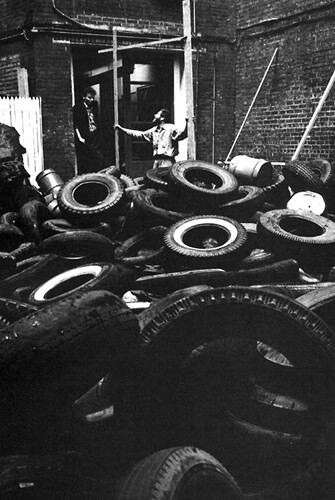

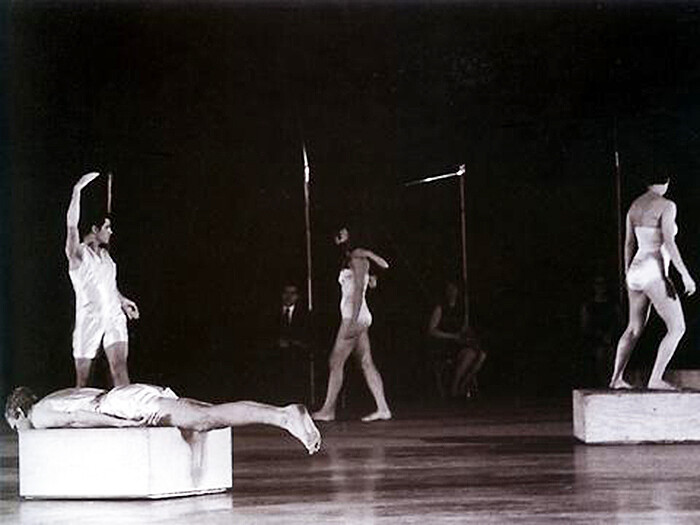

Ethan Philbrick’s Group Works

Laura Nelson

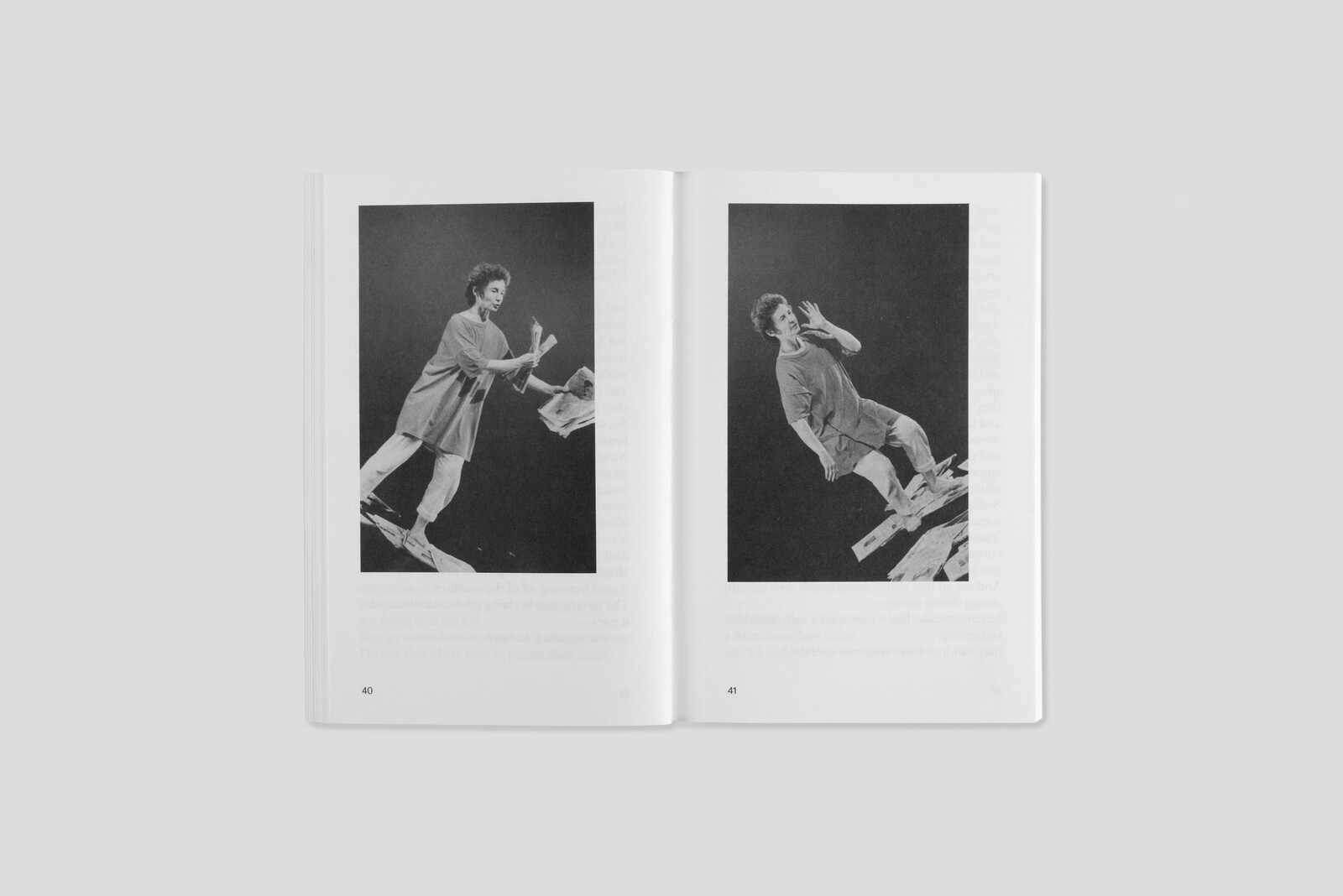

There are many ways to move through and think alongside Ethan Philbrick’s Group Works. At first glance, it’s a book of academic theory coming out of performance studies. Following a “desire for collectivity,” Philbrick takes the small-scale formation of “the group” as the locus of inquiry. He enters the text with a tentativeness toward groups, recognizing the ways that they are frequently viewed with healthy suspicion or uncritical celebration. He asks:

What kind of good-bad thing is a group to do?

When do we do things in groups, and why?

How do we group, and how does that matter?

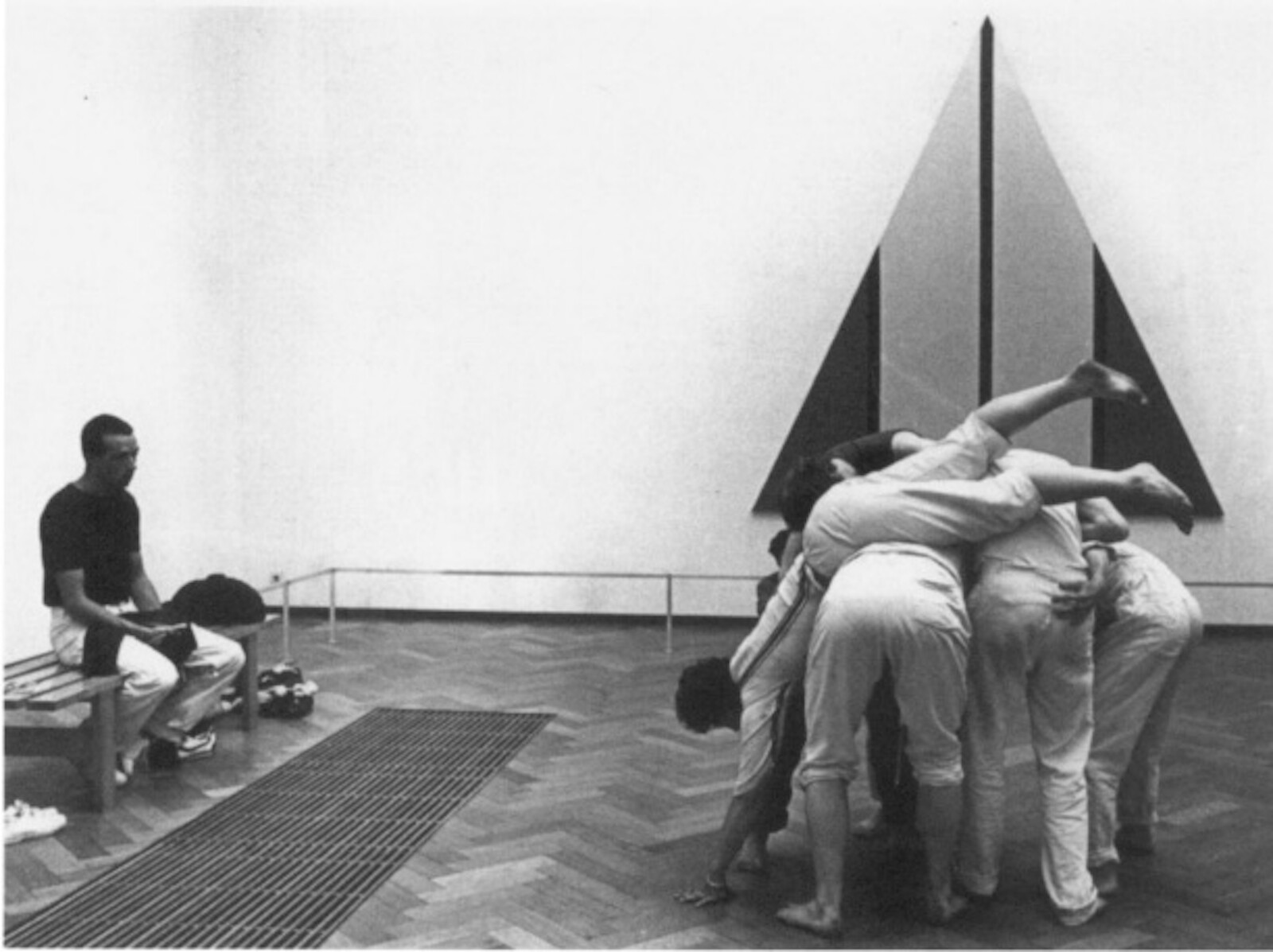

Moving with these questions, the book turns to artists experimenting with novel group formations in dance, literature, film, and music in the 1960s and ’70s. Each chapter pairs a “group work”—Simone Forti’s 1961 performance Huddle, Samuel Delany’s 1979 memoir Heavenly Breakfast: An Essay on the Winter of Love, Lizzie Borden’s 1976 film Regrouping, and Julius Eastman’s 1979 musical piece Gay Guerrilla—with contemporary works that re-imagine, re-perform, or dialogue with these experiments. Taken together, each pairing amplifies and extends the book’s central impulses to consider how groups assemble and disassemble. Along the way, Philbrick introduces a chorus of thinkers—theorists of community, theorists of in-operative community, theorists …

July 28, 2023 – Feature

Interview with P. Staff

Francis Whorrall-Campbell

I was first introduced to P. Staff’s work via a pamphlet by Isabel Waidner, produced for their show “The Prince of Homburg” at Dundee Contemporary Arts in 2019. Recently out as trans, and isolated because of the pandemic, I became obsessed with the film at the center of the exhibition—a fraught dream sequence as experienced by the eponymous prince (taken from Heinrich von Kleist’s play) interspersed with interviews with contemporary trans scholars, activists, and artists—and how Staff’s disoriented, exhausted prince, sleepwalking his way to political martyrdom, could make sense of my own fear and exhaustion as reasonable responses to structural oppression. Having missed the show, I pieced it together from the commissioned texts and a few small images, and only later watched the film, when a friend gave me a bootleg copy on a USB alongside two works by Terre Thaemlitz. I remembered how I’d felt when I first encountered the work’s archive, but now I could also see its more hopeful proposition of dreaming as resistance.

Born in 1987, Staff’s work spans sculpture, performance, installation, and film: On Venus, shown at their 2019 show at the Serpentine, juxtaposed archival footage of industrial animal farming with a poem imagining …

July 6, 2023 – Feature

Jacqueline Humbert and David Rosenboom’s Daytime Viewing

Thea Ballard

In a videotaped recording of a 1980 performance of Jacqueline Humbert and David Rosenboom’s song cycle Daytime Viewing, a woman wanders across a dim stage. She wears a bright green printed housedress—the shapeless body-concealing kind—and large fluffy slippers; she nervously settles into her spotlit destination, a chair set in profile close to a TV set. Her reflection is briefly visible on the blank screen as she fiddles with a knob to turn the set on, then, screen illuminated, she pulls up a channel displaying a nested image of another woman in profile watching TV. The tableau is soundtracked by uneasy synthesizer melody, and a voice narrating: “She was all she had, and it was more than enough for now. She was a survivor, addressing the struggle without by living within. She gathered momentum by living within, contained by a fascination with the view: this trance, this private daytime viewing where any world awaited her arrival.”

Both Humbert and Rosenboom are part of a cohort of musical avant-gardists who play with song as a form that can, often in just a few short minutes, bridge the popular inner core and absolute outer limits of American aesthetics and consciousness. Humbert designed costumes …

June 30, 2023 – Feature

The Letters of Rosemary and Bernadette Mayer, 1976-1980

Daniel Muzyczuk

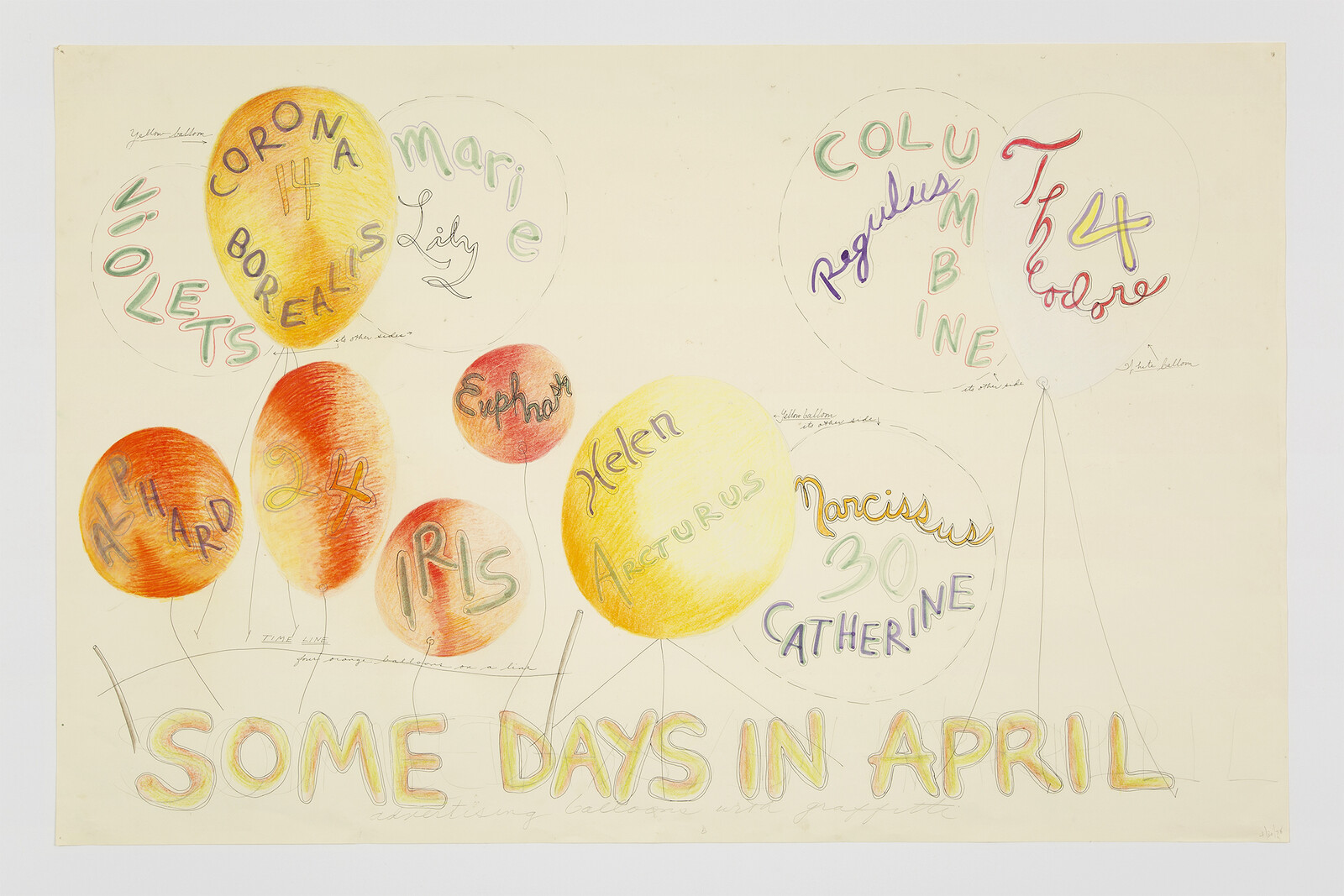

The poet Bernadette Mayer and her artist sister Rosemary began to write to each other when the former moved with her family from New York to Lenox, being deterred from phone calls by the expense. Over the four years covered by this anthology of their letters, Bernadette gave birth to two children, collaborated with her husband Lewis Walsh on the 1976 collection Piece of Cake, and worked towards her book-length poem Midwinter Day; Rosemary introduced the ephemeral installations involving snow or balloons that she called “Temporary Monuments.” Their correspondence—which complements Rosemary’s recent touring exhibition “Ways of Attaching”—both illuminates and substantiates the recent growth of interest in the sisters’ work: anecdotes of daily life mix with candid confessions of loneliness, worries about money, and, above all, attentive criticism of each other’s work and methods during these formative years in their practices.

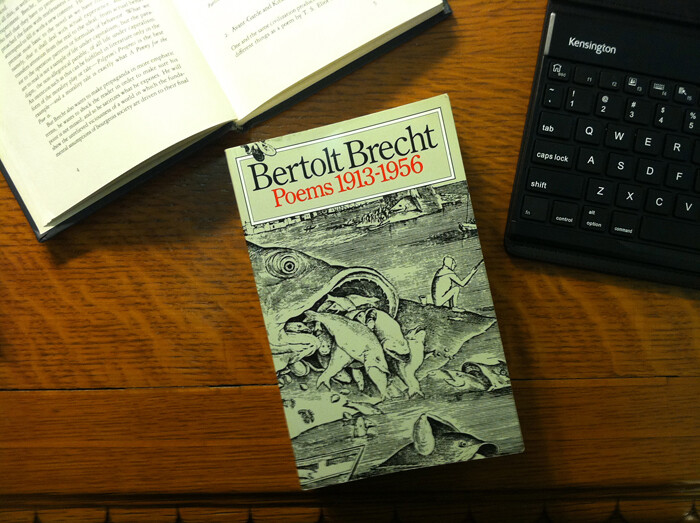

A large number of these letters end with reading (and watching) lists: Braudel, Fassbinder, Genet, Stein… Rosemary visits the cinema in New York and recommends new movies to her sister (notwithstanding the fact that these were probably hard to find in rural Massachusetts). But when she begins to examine new trends in psychoanalysis, it’s Bernadette who offers advice on where …

June 29, 2023 – Feature

London Gallery Weekend

Orit Gat

This year’s edition of London Gallery Weekend suggested something that initially surprised me: that the joy of seeing multiple shows in one weekend can be less in new discoveries than in meaningful re-encounters. Looking at Jadé Fadojutimi’s three-by-five-meter painting And willingly imprinting the memory of my mistakes (2023)—included in “To Bend the Ear of the Outer World,” an exhibition of contemporary abstraction curated by Gary Garrels at Gagosian—I thought, I still love this. I first encountered Fadojutimi’s work as part of the 2021 Liverpool Biennial; in this more formalist context I can see how the things I loved then—its blending of oil, pastel, and acrylic in one canvas, its massive presence—are in dialogue with painters I’ve been following for years. The invention and freshness of Laura Owens’s approach to painting is confirmed by every re-encounter; I continue to be amazed by how Charline von Heyl’s Circus (2022) evokes its colorful subject through abstract patterns of gray, black, and white.

Many galleries chose to dedicate their London Gallery Weekend shows to painting, and I loved many of the paintings on view. I was impressed with Shaan Syed’s four works at Sundy, which depict forms from the natural world—like the rubber plant—as …

June 16, 2023 – Feature

The World(end) of Yesterday

Xin Wang

When the HBO adaptation of the video game The Last of Us came out at the start of 2023, it already felt nostalgic for an earlier cultural moment of imagined future apocalypses. The game premiered a decade earlier among a “cohort” that included the TV series The Walking Dead (in its third season), the game Resident Evil (in its sixth), the Hollywood blockbuster World War Z, and Cao Fei’s morbidly humorous Haze and Fog, a zombie film that offered incisive observations of middle-class ennui and environmental ruin, inspired by Cao’s own fascination with eschatological imaginations in the broader culture. I remember being captivated by the zealousness of “world-building” efforts dedicated to sensationalizing its end.

In The Last of Us we follow the journey of Joel, a middle-aged smuggler who lost his daughter at the start of a global fungal pandemic, and Ellie, a ferocious queer teenager who has never experienced the world before its collapse, across America on a mission to facilitate the creation of a cure/vaccine. Many beloved zombie games at the time featured stereotypical characters or cliched trash-talk (which can become its own campy genre), but The Last of Us built indelible characters enlivened by high-quality acting. Joel’s …

June 8, 2023 – Feature

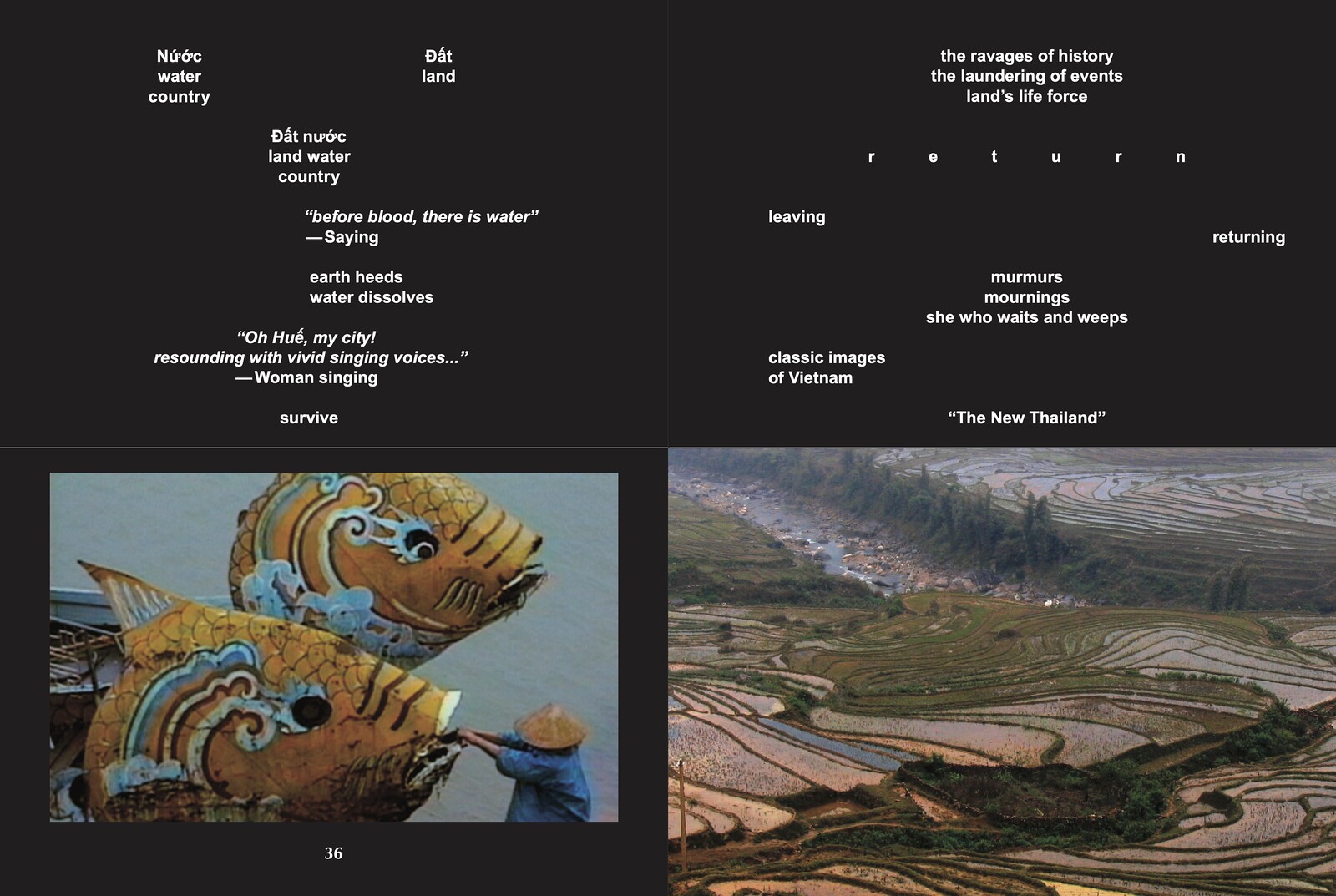

Trinh T. Minh-ha’s The Twofold Commitment

Patrick J. Reed

The Twofold Commitment revisits Trinh T. Minh-ha’s time-dipping Forgetting Vietnam (2015), a documentary feature about the mythical origins of Vietnam. Which is to say, it’s a book about a film which reflects on what the name of a country evokes of the history, people, and cultures associated with it. Seven interviews conducted between Trinh and eight media scholars and critics compose half of the book. Each approaches the filmmaker and writer’s work from a different tack, focusing on aspects of Forgetting Vietnam that are representative of her multi-hyphenate career. Irit Rogoff, for example, homes in on what it means to make a film for the feminist viewer, while Stefan Östersjö concentrates on the multi-sonic soundscapes within it. And Lucie Kim-Chi Mercier’s discussion, “Wartime: The Forces of Remembering in Forgetting,” provides important historical background about the country in question.

As a filmmaker and theorist, Trinh strives to disavow classification and impress upon her audience the necessity of the extra- and non-categorical. Thus certain terminology, like some already employed in this review, requires inverted commas more often than not. “Documentary” refers to a moving-image essay composed of Hi8 footage from 1995 and HD footage from 2012, which Trinh gathered on separate visits …

June 6, 2023 – Feature

Trevor Paglen’s unstable truths

R.H. Lossin

Trevor Paglen’s early work was made while George W. Bush was marching the United States and its allies into a war justified by an image that was neither real nor fake. Despite the convenient, racist confusion of Middle Eastern countries in the minds of many Americans, it was widely known that Iraq had no relationship to the attack on Wall Street in 2001. And so the pageantry of legitimate aggression was obliged to produce another justification for Operation Iraqi Freedom: proof that Saddam Hussein was manufacturing weapons of mass destruction. When Secretary of State Colin Powell addressed the UN Security Council in a bid to secure international sanction for the invasion, what he presented was a set of blurry, ambiguous satellite images of what appeared to be buildings. The official reason for invading Iraq was a specific, actively enforced interpretation of some grainy shapes. Before Powell’s UN speech transformed the grainy shapes into sites for nuclear weapons production, the tapestry of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937/55), which depicts civilian death by aerial bombardment and hangs at the entrance to the Security Council chambers, was covered up. Wars are always fought with propaganda, but this one began with an image whose facticity …

May 30, 2023 – Feature

Sophia Giovannitti’s Working Girl: On Selling Art and Selling Sex

Wendy Vogel

In the opening pages of Working Girl, Sophia Giovannitti—artist, writer, sex worker—makes a case for her choice of “pleasure work” over the drudgery of a day job. “When I say make pleasure work, I mean to sell sex and art,” she writes, “not because doing what you love makes work more bearable, but because the particular economic conditions in these industries facilitate maneuvers and scams that allow people to work less and do what you love more.” Given this fiery beginning, I expected a full Marxist takedown of the art market, or perhaps an angry manifesto à la Virginie Despentes’s King Kong Theory (2006). Giovannitti borrows elements from both, at a cooler temperature, as she argues for working the system to one’s advantage. Threading together memoir and criticism, her volume charts a journey through contemporary art addressing prostitution and pornography, the blind spots of movements like MeToo, the politicized actions of sex workers, and finding a way to live beyond labor.

The bulk of Giovannitti’s text toggles between a discussion of erotically charged art and her own experiences navigating sex work. Drawing from scholarship by art historians such as Julia Bryan-Wilson, Giovannitti revisits a handful of now-historical works. She considers …

May 11, 2023 – Feature

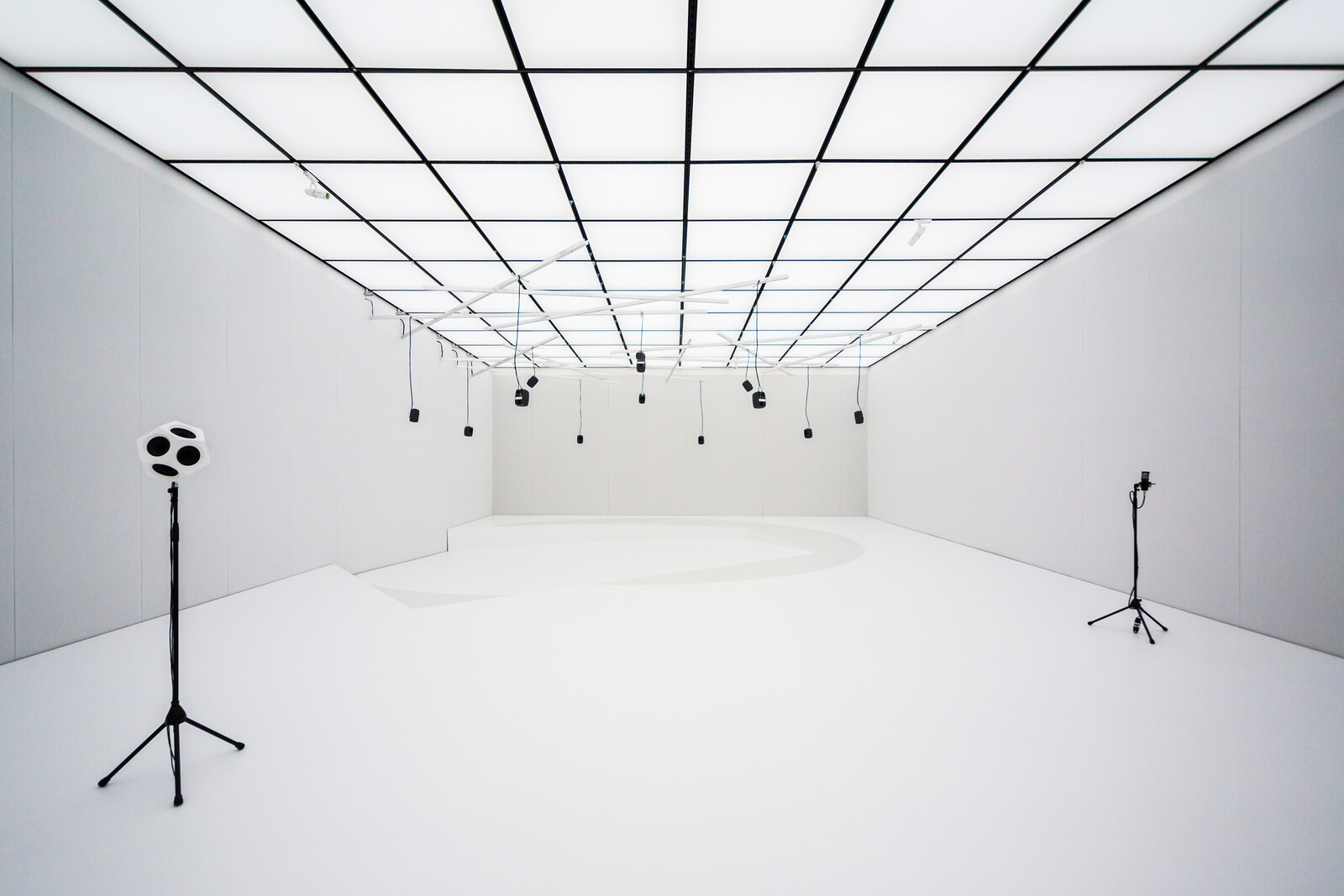

New Rules of Immersion

Chris Fite-Wassilak

At the heart of Mike Nelson’s Hayward Gallery retrospective is a wooden workbench. Chained to it is a series of Halloween masks: Frankenstein’s monster, the wolfman, a few scary clowns. The bench is embedded in a dense web of steel mesh that sprawls through the gallery, the haze of mesh dotted at points with concrete heads on hooks that bear bugged-out eyelids and gurning teeth, evidently made using the masks as casts. Studio Apparatus for Kunsthalle Münster (2014) is the high concluding point of this exhibition of Nelson’s detailed and ominous theatrical installations, fully occupying its Brutalist surroundings, as well as providing a concise summation of his work. After wandering through the creepy maze of The Deliverance and The Patience (2001), banging open dozens of doors and dodging other visitors in order to inspect each cramped room lined with cryptic clues—a pantheistic altar in one, a worn-down travel office in another—the sense of being a detective, on the hunt for the whys and whats, is heavy in the dusty air. The masks feel like a tacit acknowledgement of the roles we’re meant to play here: we’re not just any detective, we’re a B-movie detective, pursuing these ready-to-wear cinematic monsters through …

May 5, 2023 – Feature

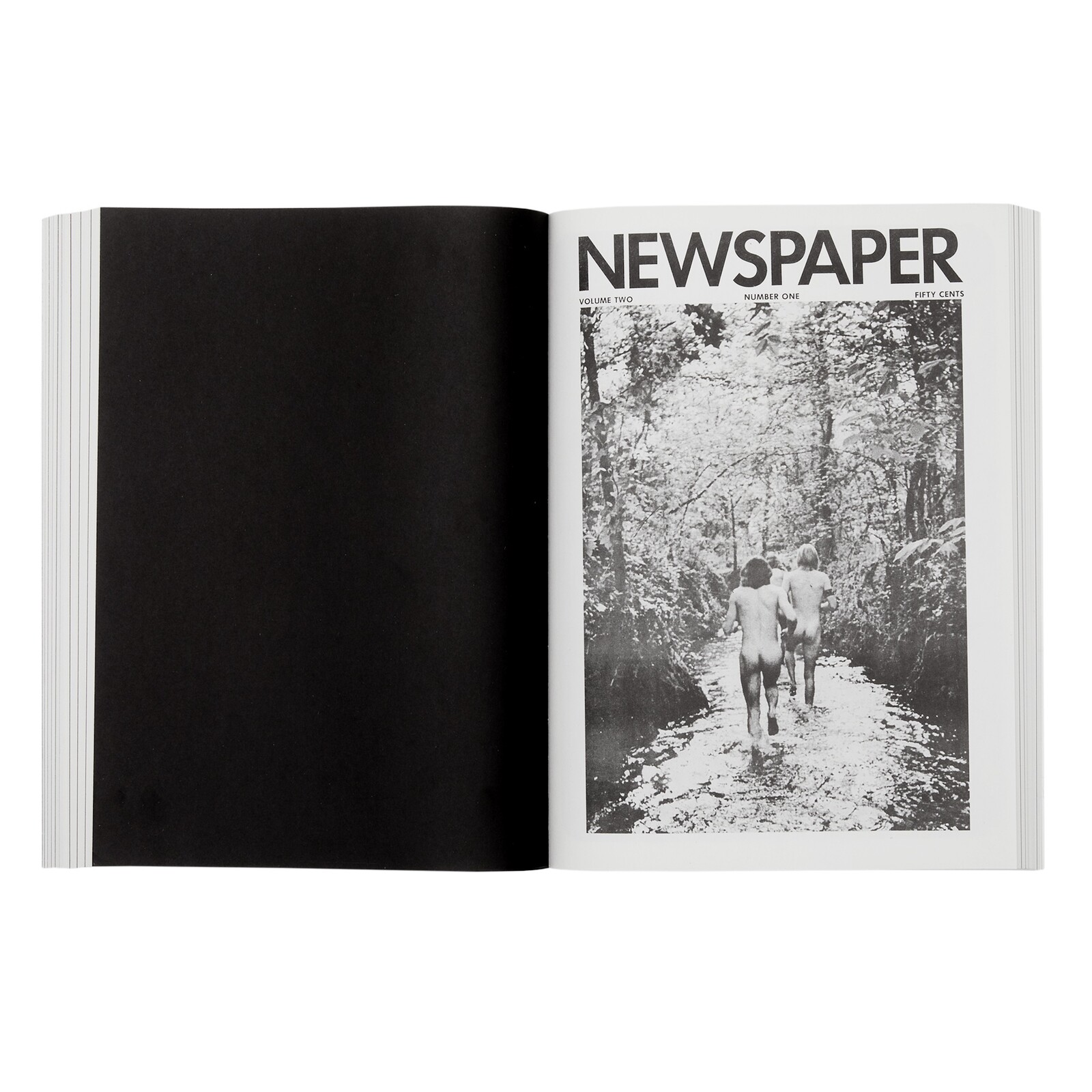

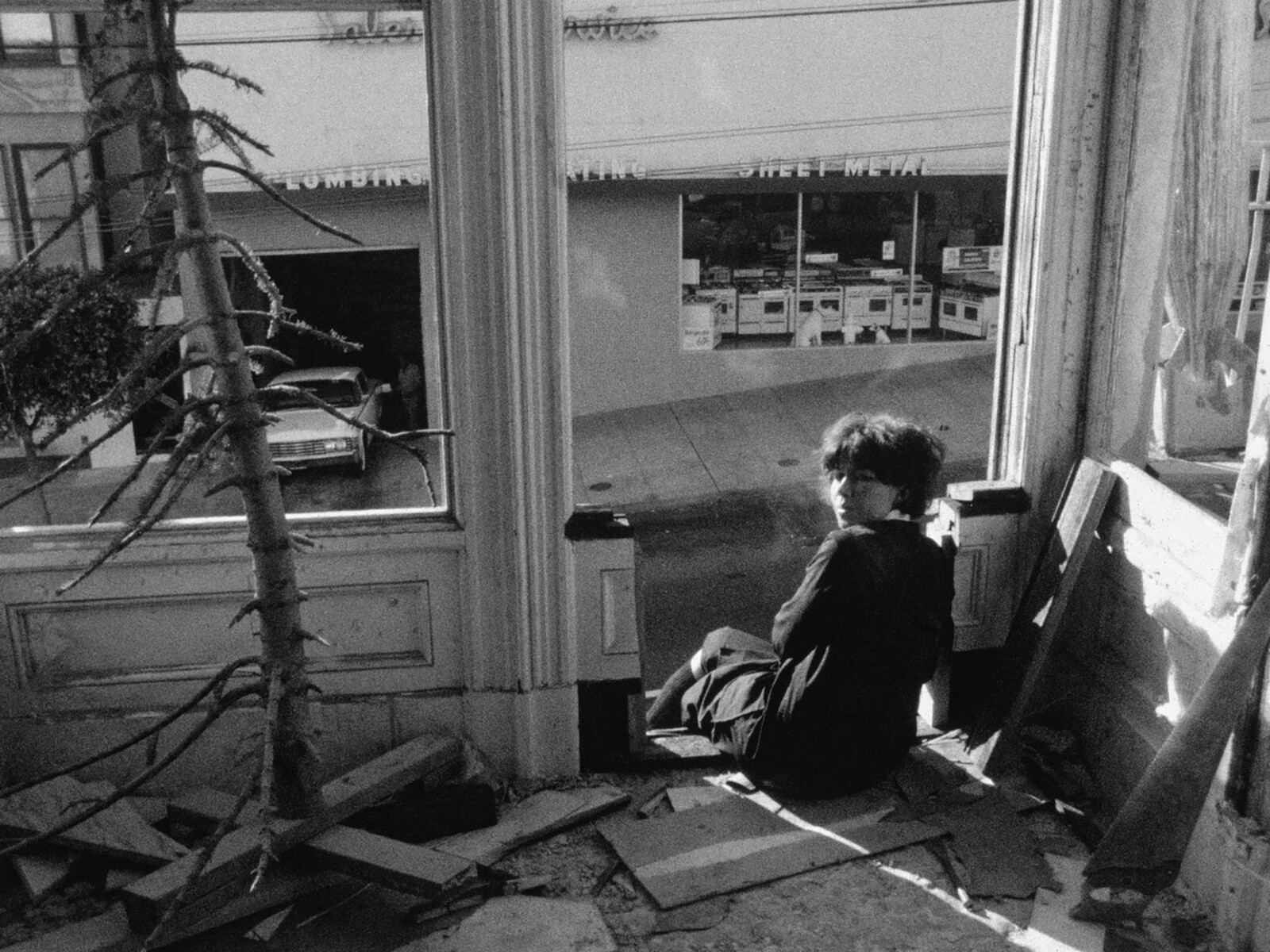

On Peter Hujar and Newspaper

John Douglas Millar

The critical literature on the photographer Peter Hujar’s work remains relatively slight, and that of value slighter still. One explanation for this is the limited primary material available; Hujar was coterie-famous in his lifetime, but never garnered the exposure that would generate a significant body of contemporary criticism. For reasons in part attributable to his difficult childhood—his father left before he was born, his mother was an irascible and sometimes abusive drinker who left him with his Ukrainian immigrant grandparents for the first years of his life—Hujar refused paternalism of any kind, either toward himself or his work, and he maintained an ascetic, almost Beckettian attitude toward speaking on behalf of either. He wrote almost nothing about his photography for publication. Many of his letters are lost. On the single occasion he was invited to speak before an audience he failed to prepare and froze at the lectern. He granted very few interviews, and in those he did allow he is a bristling, sprung, nervous subject, evasive to the point of embarrassment. In the only extensive interview he gave, conducted by his sometime lover and protégé David Wojnarowicz, almost the first thing he says is that he will not discuss …

April 28, 2023 – Feature

Claire Dederer’s Monsters

Orit Gat

I hate to admit that on my honeymoon in New York I watched Woody Allen play the clarinet at the Carlyle. My ex-husband was a huge Woody Allen fan and at the time (for the record, I was very young) I had a loose sense that Allen was bad but didn’t know the details. And I loved Annie Hall (1977): Diane Keaton, her outfits and personality, the joyfulness of it. I wanted to love it; to love it, I had to avoid difficult questions.

Or just one question. “What do we do with the art of monstrous men?” This is the issue at the heart of Claire Dederer’s book, which tackles the dilemma of whether the artist’s biography can be separated from the work. In his 1967 essay “The Death of the Author,” Roland Barthes argued that to look away from biography enables the “birth of the reader,” indicating that it’s on us—readers—to come to terms with the moral ends of looking at art. But what happens when the artist was also an abuser?

Dederer, a film critic, opens with Roman Polanski, charged with drugging and raping a thirteen-year-old girl. The book goes on to discuss Allen, Michael Jackson, J. …

April 25, 2023 – Feature

Photography Report: Imaging Racial Capital

KJ Abudu

That photography has become one of the most banal visual interfaces in twenty-first-century life is no new observation. Every day, millions of people upload scores of images to privatized servers; encounter even more images on algorithmically governed online platforms; and craft their lives in accordance with the cohesive textures of branded imagery. With this, one might ask whether photography’s critical force and relevance has waned in our image-saturated present or, conversely, if its pertinence has been heightened by the unique burden it bears in reflecting on its ethical, political, and aesthetic relation to the accumulating heap of images. Three recent photography-led exhibitions in New York City forged unexpectedly generative dialogues, laying bare photography’s embodied contradictions. These exhibitions, by LaToya Ruby Frazier, Tina Barney, and Buck Ellison, suggest that the medium’s dissonant valences symptomize the wider social contradictions of racial capital and its attendant global crises.

Installed at Gladstone Gallery is LaToya Ruby Frazier’s More Than Conquerors: A Monument for Community Health Workers of Baltimore, Maryland (2021–22)—after its first showing at the 58th Carnegie International, for which it won the Carnegie Prize. Eighteen metal IV poles are arranged into a minimal grid, their fluid-filled bags notably absent, evoking the spectral gravity …

April 20, 2023 – Feature

Jimmie Durham’s uncompleted project

Elizabeth A. Povinelli

In his 2022 book Il rovescio della nazione [The reverse of the nation], Carmine Conelli tells readers about a group of Jesuits who have just returned to the region around Naples in 1561 after years of evangelizing in the Americas. Having honed the skills of spiritual conversion across the Atlantic, they dedicate themselves to doing the same amongst the wild southern “India italiana.” Naples was not merely one moment in the terrifying spiral of European history, it was arguably ground zero. As Maria Thereza Alves has shown, the Spanish invasion of Aztec and Inca worlds carted shiploads of crated silver into the ports of Naples, kicking off price inflation throughout Europe and initiating an exploratory arms race among the major powers of western Europe to find new worlds to claim and sack. Courts heard testimony about the rights of Europeans to slaughter or enslave others on the basis of their wild nature. Soon the same was said of lands within Europe. Mad contortions of self and other ensued. “Let’s do to us what we did to them,” runs the idea, “because some of us are wild and primitive, and yet none of us will ever be like any of them, …

March 31, 2023 – Feature

A. Laurie Palmer’s The Lichen Museum

Brian Karl

You’ve probably stepped on some quite recently. Or at least walked by, or even sat on a patch, though perhaps without registering what “they” were. Ordinary, near ubiquitous, seemingly static or at least glacially slow-growing, and not particularly cute or charismatic, lichen are seldom observed consciously at all, much less celebrated, related to, or clearly understood. Like a riddle straddling the edges of the living and the physical environment—faint dustings of powder or inert, wispy fronds—lichen occupies a subliminal place in most other creatures’ perceptions and consciousness.

A. Laurie Palmer’s ongoing The Lichen Museum project, on which she has been working for more than a decade, resolves in a new book that endeavors to re-focus human attention as an act of aesthetic intervention—i.e., both conceptually as well as perceptually. A series of thematically oriented chapters (“Lichen Time,” “In Place,” and “More than One” among them) interleave excerpts from ecological texts and interviews with scientists with her own accounts of lichens and lichenology, and range from natural observation to philosophical abstraction. Reading this work thus feels like taking a series of walks with a particularly curious and sensitive companion, consistently attentive to otherwise neglected facets of the actual environment. Yet Palmer’s …

March 30, 2023 – Feature

“Anatomies of Languages Lost and Found”

Mirene Arsanios / Dina Ramadan

In her collection of essays and stories, The Autobiography of a Language (2022), Mirene Arsanios both yearns for the comfort of a mother-tongue and rejects the nationalistic confines of monolingualism. In doing so she develops some of the themes previously explored in Notes on Mother Tongues (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020) and A City Outside the Sentence (2015), a chapbook produced by Ashkal Alwan. Raised in a number of languages, the New York-based Lebanese writer and founding editor of the Arabic/English literary magazine Makhzin floats through the spaces between them in search of an ever-elusive narrative. Spanning significant personal and political changes for Arsanios, The Autobiography of a Language is an exploration of the possibilities and limitations of the narrative form, the frailty of the human body, the pain of dislocation and the trauma of lost inheritance. Through experimentation with style and form, language is dissected, its innards turned inside out, its distortions and contradictions laid bare, messy, and tangled.

Dina Ramadan: Perhaps we can begin by talking about the time frame of this book. These essays and stories come from very different moments, personally and politically, locally and globally.

Mirene Arsanios: Yes, thanks for noticing the temporal arc of the …

March 15, 2023 – Feature

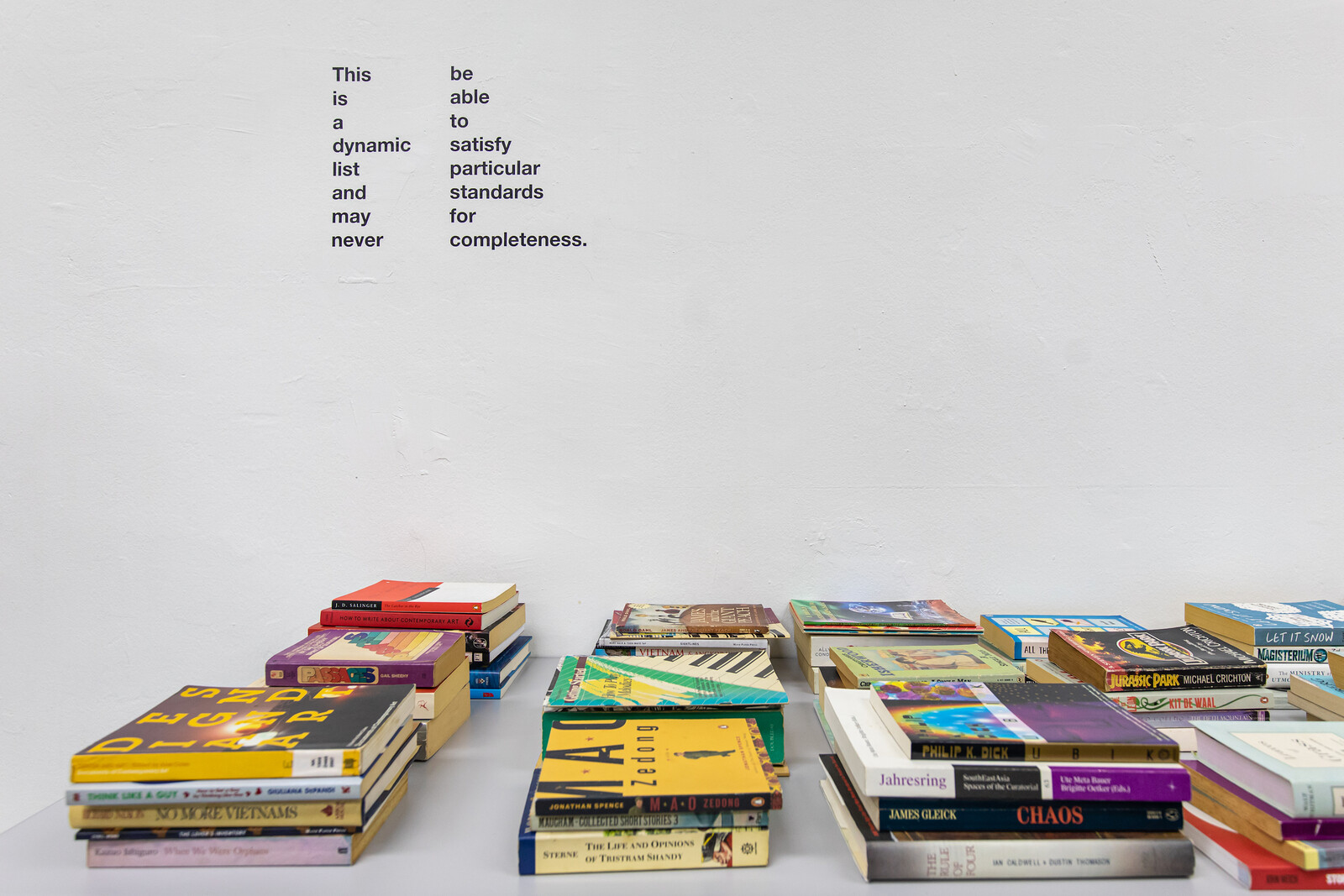

Heman Chong and Renée Staal’s Library of Unread Books

Dan Visel

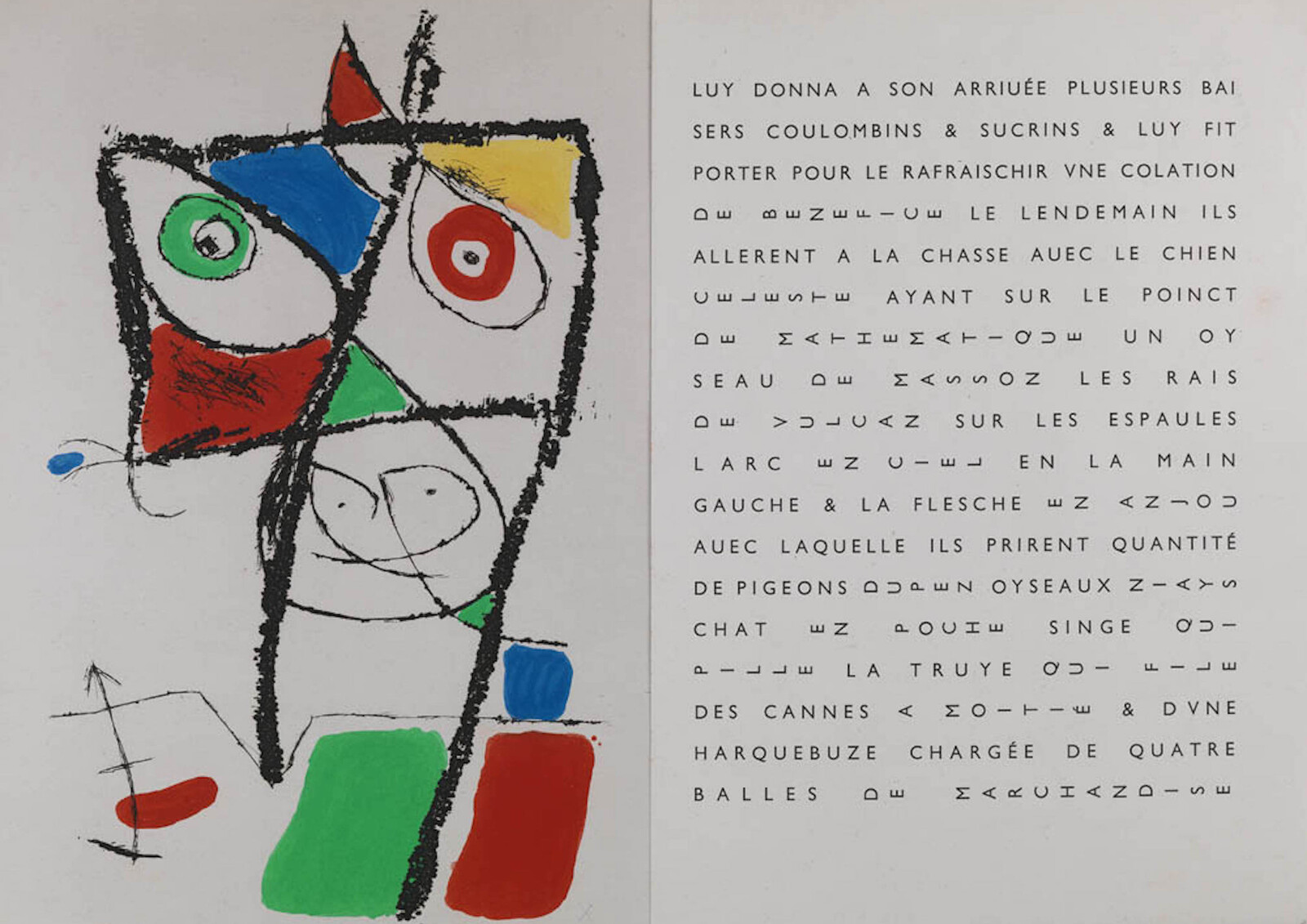

Marcel Duchamp almost had a career as a librarian. In November 1912, having given up on painting for the first time, Duchamp enrolled in library school. Soon, he started work as an intern at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, where he read about perspective and made notes for what would become The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23, often referred to as The Large Glass). His period as a librarian was a crucial moment of transition: just as he abandoned art for books, he would end up dematerializing the art object, realizing that the notes he was taking might be more interesting than the work they putatively described. The Large Glass, ostensibly the end-stage of this part of his career, is ultimately less generative than The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box) (1934), the suspiciously library-like set of notes that might combine, if assembled the right way, to make The Large Glass—or something else entirely.

A book can be seen as a node in a web of potential relationships—between author and reader, books past and future, even seller and consumer—modulated by the ecosystems around them which make such connections happen. The library is tailor-made for relational …

March 9, 2023 – Feature

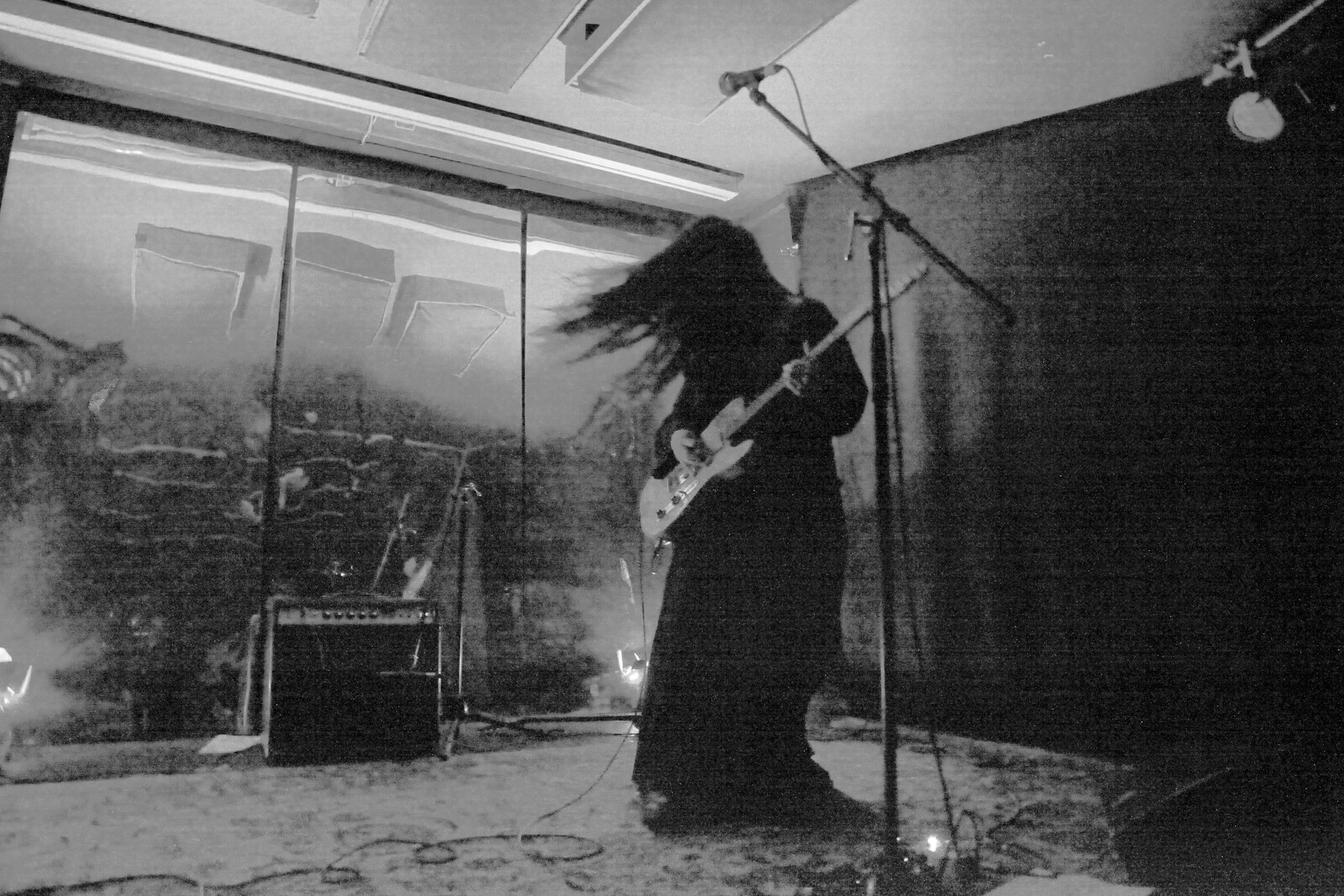

Where is the Queer Rave?

Francis Whorrall-Campbell

At the end of last year, the performance work Dyke, Just Do It (Excerpt) premiered as part of the roving queer rave INFERNO, hosted for the second time at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts. An ensemble of self-identified dykes writhed, kissed, and ripped a button-down shirt, while glitching monitors and a towering projection flickered between footage of the virile bodies, commanding slogans, and images produced through designer and director Sweatmother’s “triple-baked method,” which uses a synthesiser to warp and interact with live audio and visuals of the performers in real time. Dyke stages a version of queer sex inside the rave; a performance of sexuality which blurs the lines between diegetic and “real” desire, as the non-professional dancers turn back into ravers and even the screens could be mistaken for high-concept club design. Dyke references LGBT kiss-ins, where gay desire becomes a public theater of protest, spectacularized but not faked. Placing these gestures alongside the visual language of advertising, Dyke speculates on the possibility of seeing the media’s voyeuristic commercialization of lesbianism through the same lens, reimagining these representations of queer desire as part of a sincere, underground economy of identification.

The commercialization of queerness is not only present in …

February 28, 2023 – Feature

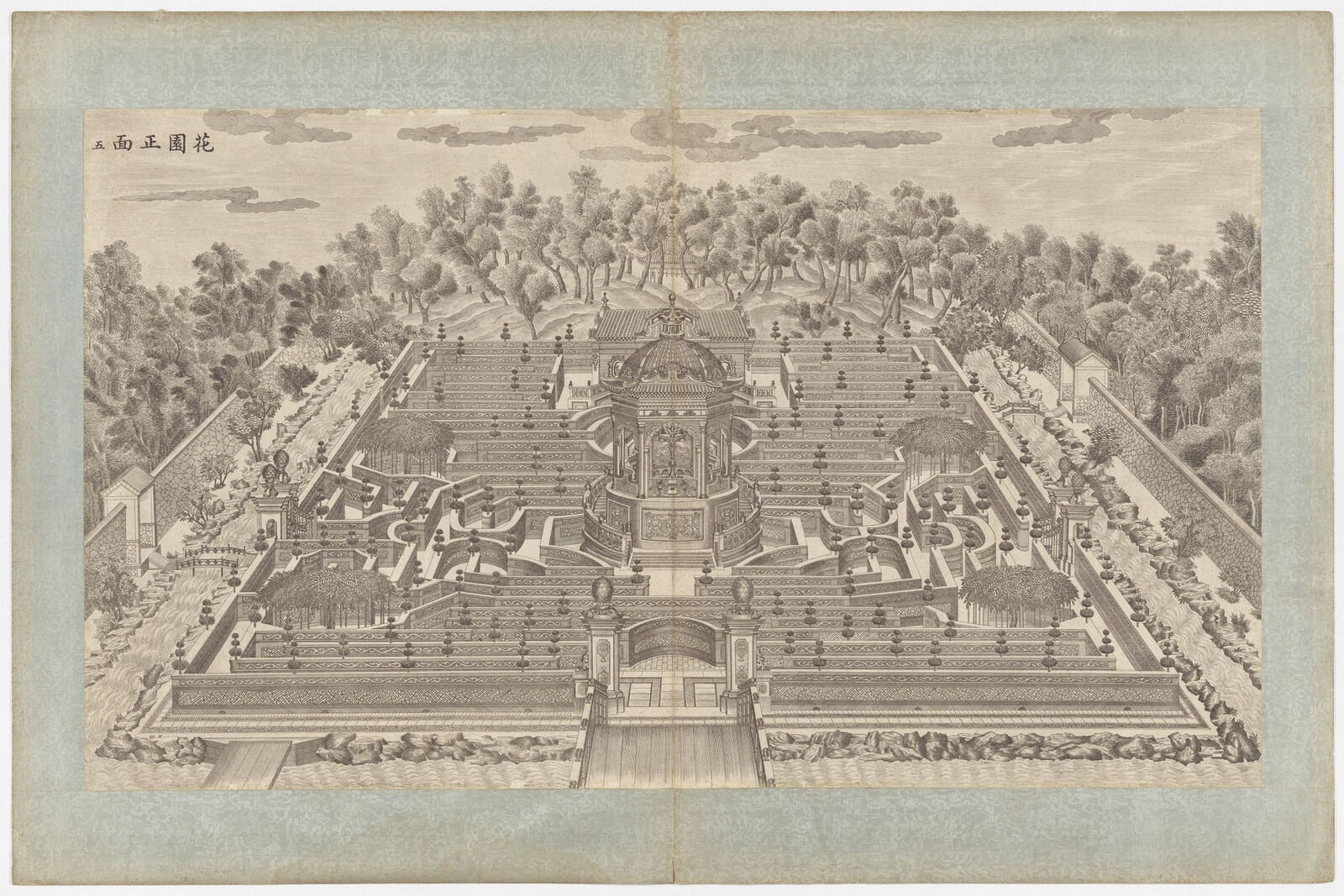

Dare to Know: Prints and Drawings in the Age of Enlightenment

R.H. Lossin

In 1784 a Berlin newspaper invited responses to the now-familiar question “What is Enlightenment?” Immanuel Kant’s reply retained the question as its title: a choice which has contributed to the sense that the question has, always, already been answered. But we keep asking it, and Kant’s “What is Enlightenment?” now ranks high among often cited and rarely read texts of the Western canon. It contains some dependable platitudes concerning free expression, as well as the exhortation “Sapere aude!” (“Dare to know!”), frequently taken as the most succinct version of his answer.

“Dare to Know: Prints and Drawings in the Age of Enlightenment” at the Harvard Art Museums brought together 150 prints, drawings, and books in order to examine how images contributed to the production and dissemination of Enlightenment knowledge between roughly 1720 and 1800. The accompanying catalog is an homage to Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie (1751-72), with twenty-six alphabetically arranged articles on topics that shape our own understanding of eighteenth-century thought. According to Elizabeth Rudy and Tamar Mayer’s entry on “Time,” the very act of looking backward as a mode of inquiry is an intellectual operation that would not be possible without the notion of history that emerged in this …

February 22, 2023 – Feature

Hermann Burger’s Tractatus Logico-Suicidalis and Róbert Gál’s Tractatus

Ryan Ruby

“All great works of literature,” wrote Walter Benjamin, “found a genre or dissolve one.” This is no more true of a novel like Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1913–27), about which the observation was made, than of works not typically recognized as literature. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) and Philosophical Investigations (1953), for example, attempted and failed to dissolve the genre of writing known as philosophy, only to found a different one, whose audience is mostly to be found in the slice of the literary field adjacent to the art world. Although the series of numbered propositions in the Tractatus owe a great deal to the pseudo-geometrical proofs of seventeenth-century philosophers like Spinoza and Leibniz, and the numbered paragraphs of the Investigations were modeled after an aphoristic tradition that extends from Epictetus to Nietzsche, both books were recognized as significant literary departures from the stylistic norms of the academic paper, and have proven more influential among those working outside philosophy proper than within it.

Putting aside fictionalizations of Wittgenstein’s life such as Bruce Duffy’s The World as I Found It (1987) and Thomas Bernhard’s Correction (1975), this genre would include David Markson’s experimental novel Wittgenstein’s Mistress (1988), Guy Davenport’s …

February 14, 2023 – Feature

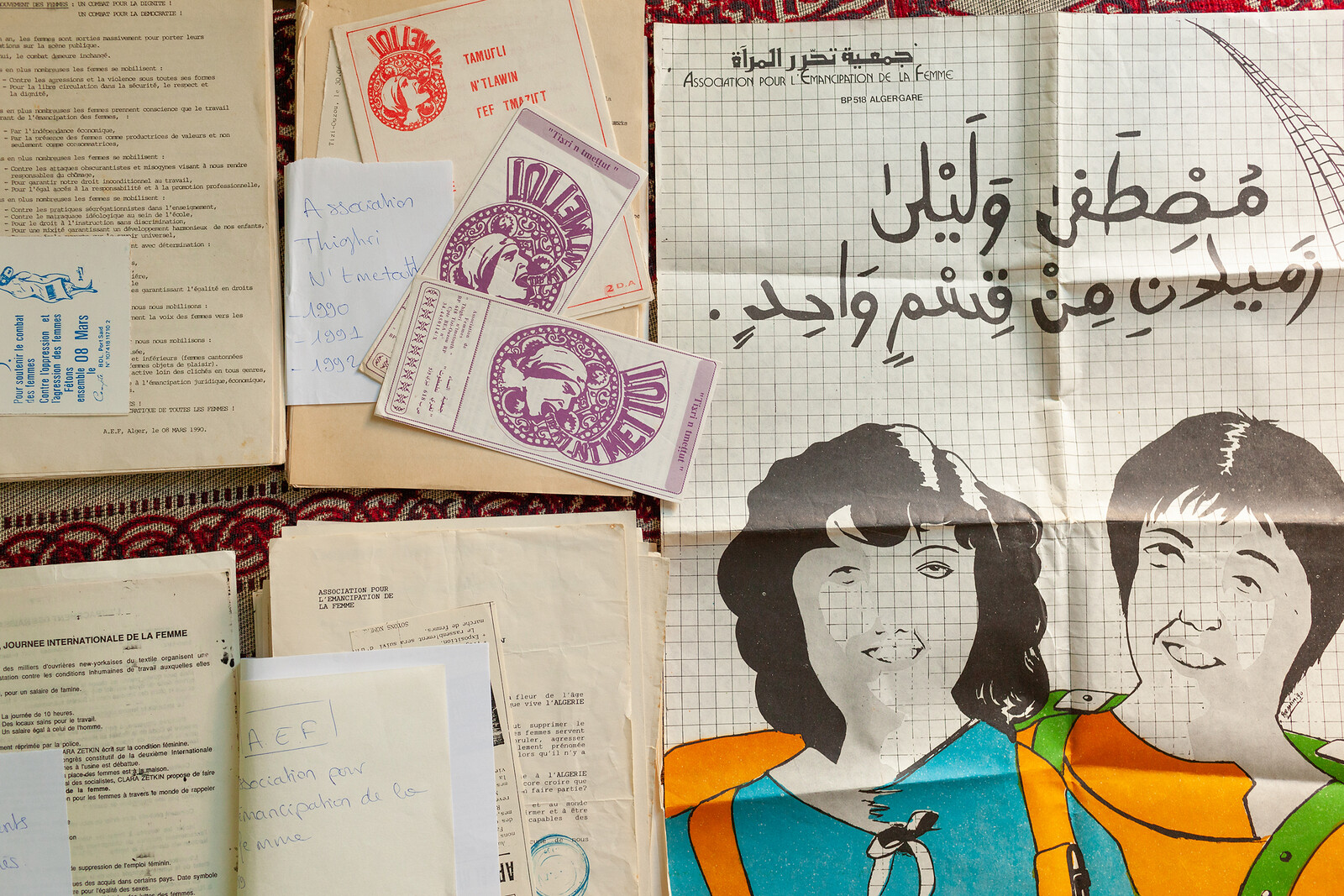

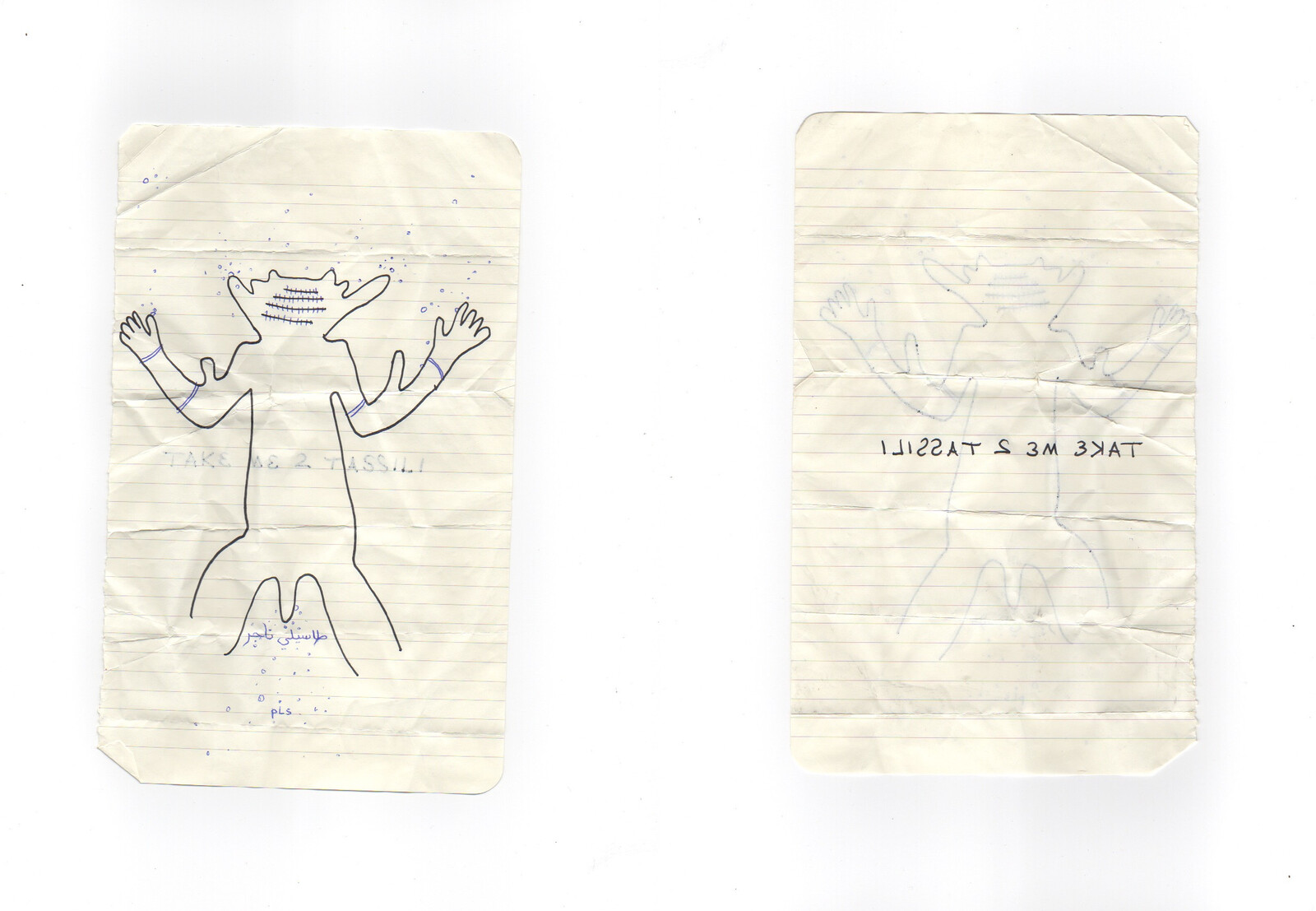

Saadia Gacem, Awel Haouati, and Lydia Saidi’s Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie

Natasha Marie Llorens

A slim ochre publication by Algerian collective the Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie, or archive of women’s struggles in Algeria, has the light, open feeling of a notebook. It was produced to accompany their installation at Documenta 15 in 2022. The book was sold out by the time I got to Kassel in early September, and I would have to wait six months to find a copy, finally, in Algiers, one of six remaining from an informal shipment that had arrived the week before.

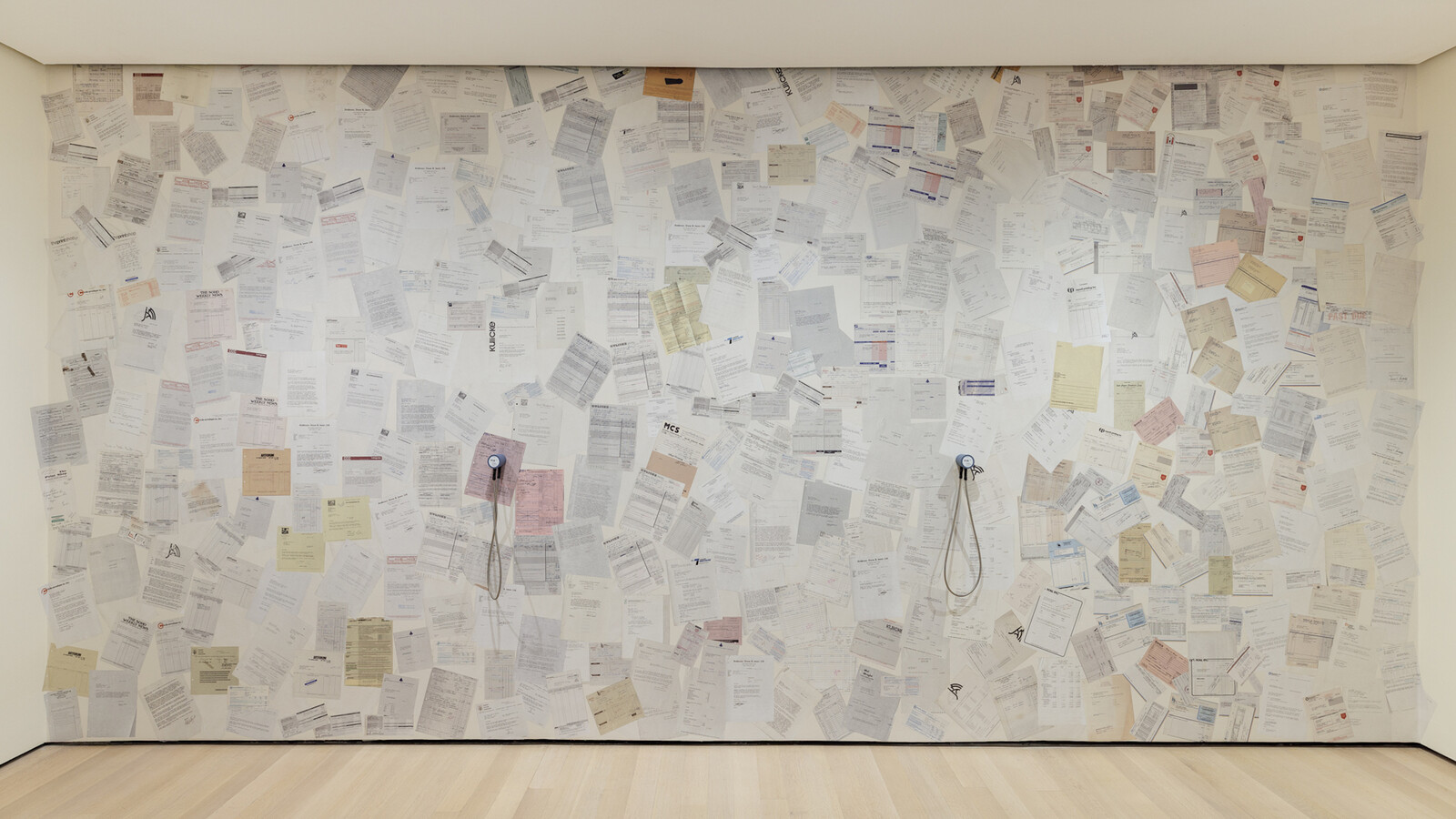

It is hard to find because the material Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie reproduces—historical documents pertaining to women’s political organizations active in Algeria between 1988 and 1991—has rarely been seen, either inside or outside Algeria. The trilingual publication (in French, English, and Arabic) presents a selection of documents and photographs; an introduction and contextualizing essay about the International Women’s Day demonstrations on March 8, 1990, by one of the collective’s members, Awel Haouati; and a socio-historical treatment of the period in question by Feriel Lalami, an Algerian sociologist, political scientist, and feminist activist. Political tracts and photographs from what the authors describe as the “democratic breach” in Algerian politics are bracketed by …

January 31, 2023 – Feature

Ričardas Gavelis’s Vilnius Poker

Daniel Muzyczuk

Begun in the late 1970s and only published in 1989, Ričardas Gavelis’s novel Vilnius Poker presents a nightmarish vision of Lithuania under Soviet rule as a rotting corpse, riddled with resentment and shot through with conspiratorial thinking. If the book feels newly relevant today, it is because it grounds a study of the political efficacy of conspiracy theories in close observation of the humiliating effects of colonial violence upon a populace. Gavelis’s novel examines connections between this phenomenon—in which paranoid conspiracies focused on abstract enemies, such as western liberalism, are marshalled in support of authoritarian regimes—and the decline of socialism in Eastern Europe.

Vilnius Poker is divided into four sections, each narrated by a different character. The eponymous city is at the epicenter of a plot orchestrated by a network of forces which, in keeping with their shadowy nature, are referred to as THEM. THEY have agents everywhere. THEY are strong in the Soviet government, but THEY are also working on the other side of the Berlin Wall. Indeed, THEY have infiltrated every global power. In Vilnius, THEY seek to turn all inhabitants into mindless followers. Vytautas Vargalys, who works at a library, believes that the final battle between the …

January 27, 2023 – Feature

An Expanded Cinephilia

Lukas Brasiskis

The Cinema Batalha in Porto was a landmark in the city’s film culture and played an influential role in shaping the cinephilia of generations of residents from its opening in 1947 through to its closure in 2003. The Batalha Film Center, which opened in December, occupies the same modernist building designed by Artur Andrade and responds to the rise of new, expanded approaches to cinema. Its inaugural program consisted of a complete retrospective of films by Claire Denis; “Politics of Sci-Fi,” a screening program curated by artistic director Guilherme Blanc and chief programmer Ana David; Premium Connect (2017), a video installation by French-Guyanese artist Tabita Rezaire that draws on a scene from The Matrix (1999); and a number of special events and discussions.

“Politics of Sci-Fi” explored the interrelation between the genre and politics, presenting a diverse range of international films across seven conceptual chapters. Sci-fi films, as this program makes clear, do not only predict but also shape political futures; in turn, the political contexts in which such films are made can influence their production. Among the works shown was The War Game (1966), Peter Watkins’s anti-war mockumentary originally made for the BBC and suppressed in the UK for …

January 25, 2023 – Feature

Grids and Clouds

Caterina Riva

Meta is a collaboration with TextWork, editorial platform of the Fondation Pernod Ricard, which reflects on the relationship between artists and writers. Following on from her essay on the work of Benoît Maire for Textwork, the curator Caterina Riva considers how the artist’s attitude towards waste and recycling resonates with her own writing process.

Finding the right tone and structure to tackle Benoît Maire’s oeuvre was tough. My hunch was to adopt a journalistic approach—more New Yorker culture desk than contemporary art analysis—something that could bypass art criticism’s claims to objectivity, but also avoid a personal subjectivity that might risk alienating the reader. After having assembled information from and around the artist, i.e. the evidence, I had to establish my vantage point and the voice in which to make intelligible the cloud of philosophical, digital, and painterly information that surrounds and feeds Maire’s artmaking. When I studied Curating, one professor would insist on the foreground, background and middle ground as strategies to imagine the layout of an exhibition; it struck me that these three concepts could lend themselves to writing, and to this author, writing in her second language, trying to negotiate her materials and ideas within an ongoing …

January 13, 2023 – Feature

The Cartoon Body of Boris Johnson

Julian Stallabrass

Boris Johnson, with his shambolic, lumbering presence, toddler’s hair, and talent for PR stunts and gaffes, was a lavish gift to cartoonists. So it made sense that, to mark his ousting as Britain’s Prime Minister in summer 2022, the Cartoon Museum in London should stage an exhibition laying out his extraordinary trajectory from the city’s mayor to champion of Brexit and divisive national leader. Johnson is a symptomatic as well as an eccentric figure, and this record of his presence in cartoons sheds light on wider issues with ramifications beyond the United Kingdom: the symbiosis between branded politicians and cartoonists, the bodies of populist leaders, and the role of revulsion in contemporary politics.

Cartoonists tend to fix upon those parts of Johnson’s body that generally go unmentioned in technocratic political discourse—particularly his arse. The first images the viewer encounters are fairground figures by Zoom Rockman of the kind you put your head through to be photographed (a reminder of the medieval stocks). In one of these, the user’s head appears through the arse of a flag-waving PM. And ever since his time as the Mayor of London, veteran political cartoonist Steve Bell has replaced Johnson’s face with an arse (a matter …

January 11, 2023 – Feature

Persistence or Renewal? On Gregory Halpern’s “19 Winters / 7 Springs”

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

Over the past decade, Gregory Halpern has become an influential figure in American art photography, principally through the release of several wildly successful photobooks. Virtually all that work has centered on the postindustrial Midwest, so that it seems especially apt that the Transformer Station, in Ohio City, Cleveland should host his first major US solo exhibition.

“19 Winters / 7 Springs” comprises forty-one photographs and three floor-standing sculptures, all made in or depicting Halpern’s hometown of Buffalo, NY. In a faint echo of the geography of the region, in which Buffalo and Cleveland share a shoreline with the vast Lake Erie, this former substation has been refashioned into two reading rooms and twin gallery spaces linked by a single corridor. Upon entry, one finds at right a gallery framed by a large, Edenic portrait of a young white man perched on crutches beneath an immense tree, the bushes behind him a buoyancy of yellow flame (Untitled, 2004–2022). At left, in the Crane Gallery, Halpern shows a diminutive portrait of a muddy young African American student listing faintly after football practice, the looming gray trashcan beside him seemingly ready to swallow his weary frame whole (Untitled, 2004–2022). The two portraits map …

December 22, 2022 – Feature

What’s next?

The Editors

The past year has been marked by the restoration of normality to some parts of life and the transformation of others. So it was no surprise that, when we asked contributors to pick their highlights from 2022, so many nominated shows engaged with the question of what should be restored and what abandoned, what preserved and what confined to history. These creative responses to the moment took forms as varied as archival approaches to activist art, interventionist challenges to censorship, the rewriting of history, dispersed curatorial practices, and collective exhibition-making. With the new year we too will be changing, expanding our coverage to reflect the dissolution of old forms and the emergence of new ones. Look out for forthcoming announcements, and we’ll be back on January 6. In the meantime, happy holidays. The Editors

Hallie Ayres

I’ll take any opportunity to see work by the architecture collective Ant Farm. Most recently, their Dolphin Embassy project appeared in “Who Speaks for the Oceans?” at Baruch College’s Mishkin Gallery. Compiling work that ranged from whimsical to urgent, the quietly transcendent show offered a necessarily polyvocal approach to decentering the Anthropocene. Other stand-outs within the show included Myrlande Constant, Will E. Jackson, and Pia …

December 2, 2022 – Feature

This Machine is Broken: the Making of Populist Contemporary Art in Warsaw

Jakub Gawkowski

What if a contemporary art center, a space usually conceived as a laboratory for progressive ideas, became the opposite: a tool for promoting xenophobia, exclusion, and far-right propaganda? Under director Piotr Bernatowicz, the once-renowned Ujazdowski Castle CCA in Warsaw has pivoted to align with the values of the governing, populist Law and Justice Party that appointed him. Its latest show, “The Influencing Machine,” curated by Aaron Moulton and featuring regional and international artists from Chris Burden to Constant Dullaart, claims to tell the story of how the Soros Centers for Contemporary Art (SCCA) that sprang up across Eastern Europe in the 1990s were instruments of propaganda. More than anything, however, it shines a light on Polish nationalist populism and its conflicted, contradictory cultural-political mindset.

Since becoming director of Ujazdowski in 2020, Bernatowicz’s controversial program has sought to prove that contemporary art can be a place for conservative and nationalist values, and that an avant-garde might look back to the past, instead of forward to the future. The role of an experienced curatorial team in developing the program has been taken by loyal collaborators who not only lacked their expertise but even took to warning the public of the deleterious …

November 29, 2022 – Feature

Mame-Diarra Niang’s The Citadel: a trilogy

Sean O’Toole

Paris-based artist Mame-Diarra Niang’s debut book, The Citadel: a trilogy, is a plush and enigmatic showcase of her interest in “the plasticity of territory”; more pointedly, of her use of the landscape genre as self-reflexive tool of knowing, basically as mirror. The multi-part book compiles discrete photo essays produced—and previously exhibited—in two African cities, Dakar and Johannesburg, between 2013 and 2016. The publication makes concrete the formal arrangement of each essay, as well as unifying them under a common rubric. The Citadel follows a number of ambitious books describing Africa’s complex urbanism, among them Guy Tillim’s Jo’burg (2005) and Joburg: Points of View (2014) and Filip De Boeck and Sammy Baloji’s hardcover tome Suturing the City: Living Together in Congo’s Urban Worlds (2016). Its distinction emerges out of Niang’s willingness to subordinate documentary exegesis to mythic questing.

The tension between self and place is central to the slow crescendo proposed by the three individually titled and numbered books—Sahel Gris, At the Wall, and Metropolis—that constitute The Citadel. “It is important to me to address the representation of the self as a body that does not reduce itself to flesh, but possesses many places ‘without place’,” Niang stated in a 2015 …

October 31, 2022 – Feature

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie’s Beautiful, Gruesome, and True

Orit Gat

“What can you say about violence except that it should not happen?” asks Amar Kanwar. Writing from a conviction that art matters in the face of the “forever wars of our time,” art critic and journalist Kaelen Wilson-Goldie explores the works of three artists: New Delhi–based Kanwar, Mexican artist and activist Teresa Margolles, and Abounaddara, a collective of filmmakers who released weekly videos online from the beginning of the Syrian Civil War showing the realities of life under the regime. In making art, Wilson-Goldie argues, each found a space in which to reflect on the politics of the places they are from in ways that go beyond the documentation of violence, to transformative effect.

In her chapter on Abounaddara, Wilson-Goldie follows the collective in showing how life in wartime is shaped by conflict but, crucially, not wholly defined by it. The work of Kanwar, meanwhile, offers an example of how art can engage with popular struggles over labor rights, land, and resources. He’s been returning to the Indian state of Chhattisgarh ever since labor activist Shankar Guha Niyogi was murdered in 1991, on the day before Kanwar had arranged to film him. Writing about Margolles, Wilson-Goldie starts with her work …

October 28, 2022 – Feature

“Ultra-clearness”

Andrés Jaque / The Editors

Andrés Jaque is an architect, writer, and curator whose work considers how architecture shapes our societies. In 2003 he founded the Office for Political Innovation, an architectural firm operating at the crossroads of research, design, and ecological studies to foster debate around the wider ramifications of human intervention into the landscape.

These projects frequently address the literal and figurative “transparency” of buildings. When commissioned in 2002 to design a hoarding that would hide the construction of the Cidade da Cultura de Galicia from view, for instance, Jaque proposed “twelve actions to make Peter Eisenman transparent.” Arguing that the site was “already concealed because it could hardly be understood by anyone not directly involved in its management,” he instead invited the public in to discuss its economic, environmental, and political impacts.

Jaque’s 2012 intervention into Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich’s Barcelona Pavilion foregrounded the contributions of water lilies and cats to a modernist masterpiece; commissioned by the 2021 Performa Biennale, Being Silica reproduced a fracking site in a Manhattan skyscraper. Now director of the Advanced Architectural Design Program at Columbia University, Jaque was co-curator of Manifesta 12 and chief curator of the 13th Shanghai Biennale. This interview is part of the …

October 25, 2022 – Feature

Mexico City Roundup

Gaby Cepeda

Mexico City’s fall openings are marked by a theatrical turn. The most overt expression is “Destino” [Destiny], organized by Mario García Torres at Museo Experimental El Eco. Displayed on a screen in the museum’s narrow entranceway is Disculpa [Apology] (2022), a video by García Torres and Eduardo Donjuan that sets the scene. The buffoonish face of Alejandro Suárez—a comedian well-known to Mexicans born before the turn of the millennium—performs a monologue in a painstaking, over-acted way. He goes on about his agent bringing him the offer to participate in this show, talks of “an air of the avant-garde” as a reason for accepting the invitation, and digresses on the similarities between art and spectacle. There are passing references to the Museo Experimental El Eco’s history: first established as an art institution in the 1950s, it later became a gay bar, a punk bar, a restaurant, a boxing gym, and a small theater, before reverting to its original function. At one point, Suárez recites a poem and then dances enthusiastically—it’s equal parts kitsch and unsettling to watch. He touches on some of Mario García Torres’s enduring fixations, evident in his earlier monologues and performances including I Am Not a Flopper (2007) …

October 17, 2022 – Feature

London Roundup

Chris Fite-Wassilak

There’s a moment towards the end of Jumana Manna’s film Foragers (2022), in her show of the same name at Hollybush Gardens, that stuck with me through Frieze week. After an hour spent following Palestinian foragers searching for a plant the Israeli authorities have deemed illegal to pick, the viewer is plunged into darkness shot through with brief glimpses of rusted orange-red semicircles. Slowly, the image resolves into low foliage illuminated fleetingly by a patrol car’s rotating beacon lights. This momentary break from reality—from documentary-style footage towards something resembling abstract animation—resonated with a wider disorientation I felt across some three-dozen exhibitions and an art fair. I don’t know if you can call it a theme, a trend, or a vibe, but it is perhaps best described as a sense of unease.

Such unease seems to prompt the creation of shelters or safe-spaces in works as disparate as the dark cork-lined walls of William Kentridge’s retrospective at the Royal Academy and Olukemi Lijadu’s cloth-lined viewing room for her film Guardian Angel (2022) at V.O Curations. When time is jumbled or out of joint, art can be a means to step ever so slightly back, to gain perspective, and to reimagine a …

October 12, 2022 – Feature

“The little bird must be caught”

iLiana Fokianaki

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art elected to establish an annual festival addressed to a changing world and proposing “survival strategies.” Now in its thirteenth year, Survival Kit takes place under the shadow of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and its implications for a country in which around one quarter of the population are Russian speakers.

An exhibition curated by iLiana Fokianaki and taking inspiration from the “Singing Revolution” that preceded the Baltic States’ independence from the USSR has clear resonances with the present situation in Eastern Europe, but also reverberates more widely. Poetry, music, and song are figured by artists from Andrius Arutiunian to Wu Tsang as powerful expressions of resistance to imperialism, not only as the vehicles by which marginalized traditions are transported into the future but also as defiant expressions of feelings that cannot be suppressed. After seeing the exhibition in Riga last month, we talked to Fokianaki about a world in flux and the role of art within it.

art-agenda: A year ago you proposed a show which would consider the impact of rising authoritarianism on issues of national identity and free speech through the lens of Latvia’s …

September 30, 2022 – Feature

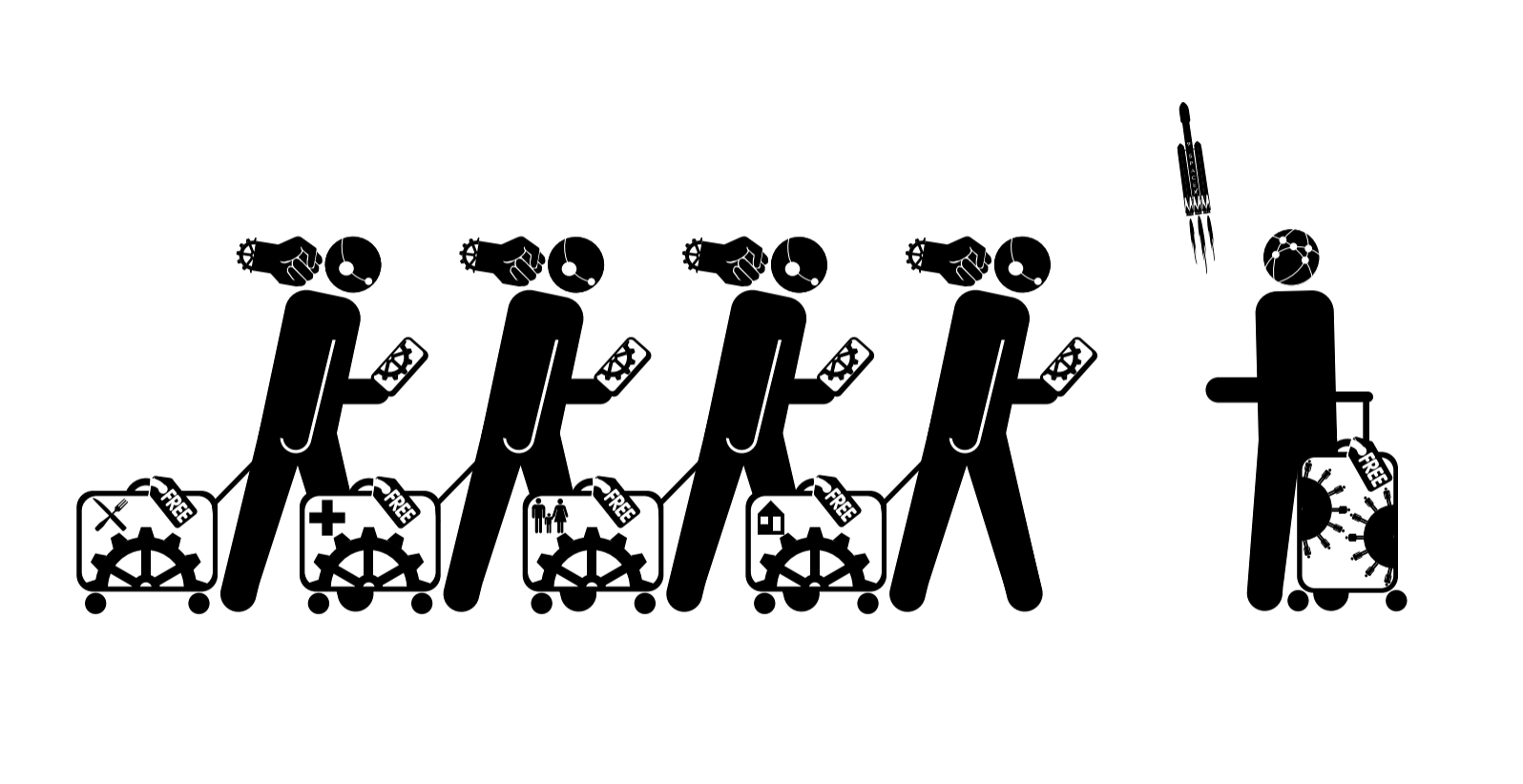

M. E. O’Brien and Eman Abdelhadi’s Everything For Everyone

Andreas Petrossiants

In her Manifesto for Maintenance art, 1969!, Mierle Laderman Ukeles asked: “after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?” If sectarian communism and reformist socialism do not challenge the classical Marxist separation between productive and reproductive labor, then what else could revolution lead to but a perpetuation of the same hierarchies by different names? Lizzie Borden’s documentary-styled film Born in Flames (1983) provided one answer to Ukeles’s question: after the United States’ transition to state socialism, violence against women, unremunerated labor, and homophobia remain rife, even amongst “comrades.”

M. E. O’Brien and Eman Abdelhadi’s speculative fiction offers another. It imagines a future in which rebellions have brought about post-capitalist worlds: commodities and the state have not only been abolished, but forgotten. The authors—performing versions of themselves five decades from now, and two decades after the insurrection reached New York—interview twelve different characters for the “New York Commune Oral History Project.” Beginning with an introduction from the future that doubles as a primer on communization theory, it’s an impeccable act of world-building. Intimate, at times confrontational, dialogues address the localized but globally oriented insurrections that brought down capitalist, white supremacist states throughout the world. The interviewees …

September 29, 2022 – Feature

“Life after ruins”

Kateryna Iakovlenko

On March 18, a few days after the writer and curator Kateryna Iakovlenko left her hometown of Irpin in Kyiv Oblast, she learned that her apartment had been hit by a rocket. In August, having returned to the city, she organized an exhibition in what remained of her home. Titled “Everyone is afraid of the baker, but I am grateful,” the show featured work by Katya Buchatska, Mark Chegodaiev, Sasha Kurmaz, Roman Mykhailov, Anatol Stepanenko, Stas Turina, Tamara Turliun, and Anna Zvyagintseva. In this conversation over email, she tells us how the project explored the possibility of articulating trauma, the role of archives, and what it means to live after ruins. Not least, she draws attention to the many artists in Ukraine who have continued to work through the invasion of their country, and in resistance to it.

art-agenda: How did you learn that your apartment had been ruined, and why choose to make an exhibition in the space when you returned to Ukraine?

Kateryna Iakovlenko: Six days after I arrived in Vienna, I saw a report that the remnants of a rocket had hit our building. I learned from my neighbors’ posts on social media that it had …

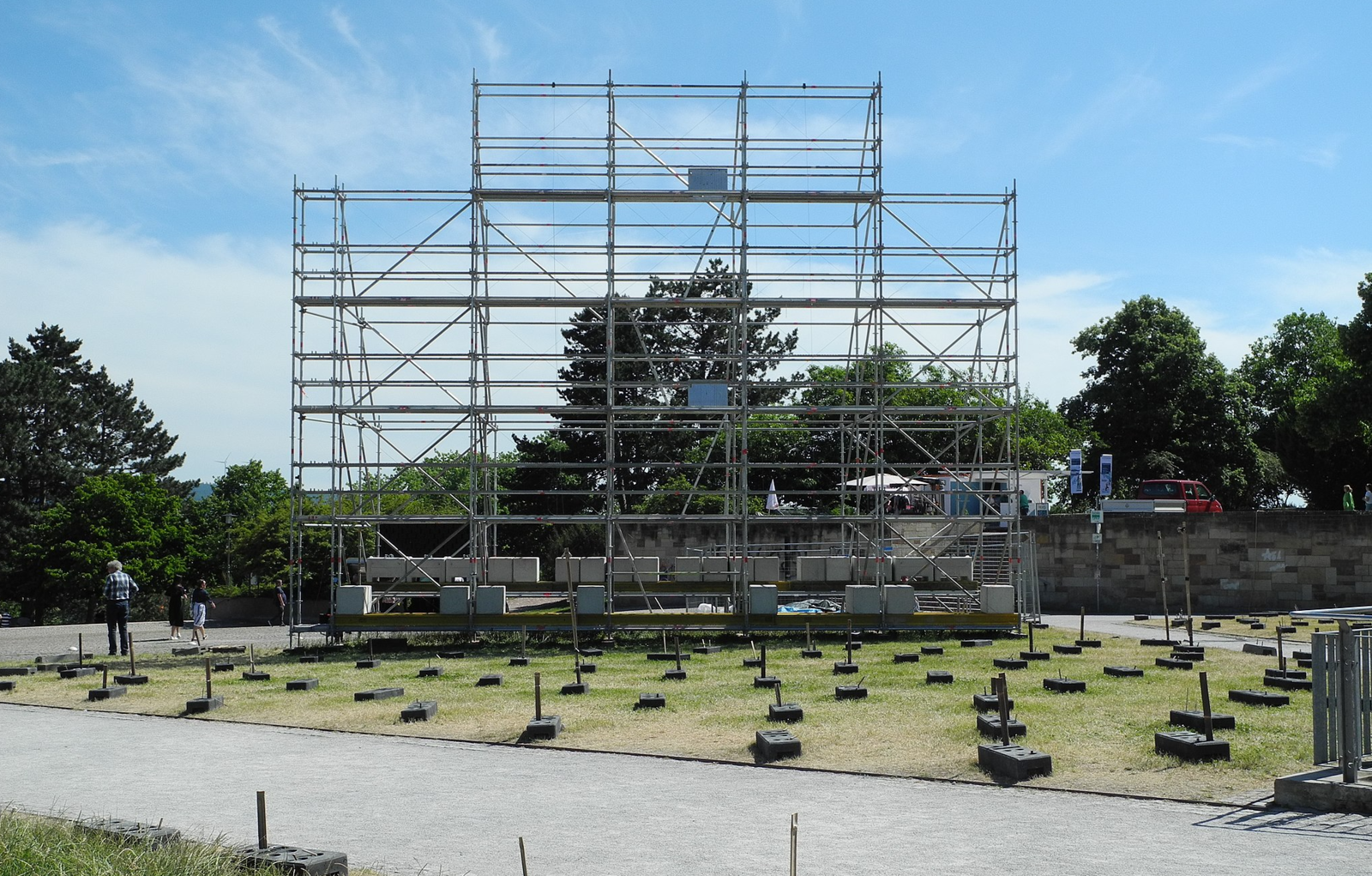

September 21, 2022 – Feature

A short and incomplete history of “bad” curating as collective resistance

Gregory Sholette

In the last of our dispatches from Documenta 15 over the course of its 100 days, Gregory Sholette defends the exhibition’s daring, decentralized curation, placing it in the context of artistic and activist movements from the nineties to the present, and contrasting it to the presentation of the Berlin Biennale.

Between the start of this year and the end of September, the artistic universe has delivered up an increasingly ominous sequence of events that, for me at least, resembles the tangled history of decentralized curating, the recrudesce of which feels downright spooky. Der Spiegel’s recent exhortation regarding Documenta 15 that “the German cultural sector has a big problem,” for instance, made me think of a threat made by Walter White in Breaking Bad: “There will be consequences.” Given that much of the criticism of Documenta 15 has focused on alleged curatorial inadequacies—and has included not only menacing editorials recalling sensational crime drama, but direct threats of violence against curatorial staff and artists—it feels pertinent to ask: a big problem for whom? And if the show’s decentralized curating has been attacked as “bad,” then according to what reputed standards?

In 1998, as the recently hired Curator of Education at New York’s …

September 16, 2022 – Feature

“Fire Complex”

Uta Kögelsberger / Julian Stallabrass

In 2020, the Castle Fire wildfire swept through 174,000 acres of Sequoia National Forest, destroying an estimated 14 percent of the world’s giant sequoia population. Uta Kögelsberger embarked on a series of works and actions to render the destruction and its wider implications palpable, and to start to restore the land.

In her multi-screen video work Cull (2022)—which has been shown in different iterations in Los Angeles, London, and online—a dire spectacle unfolds before the viewer: a burnt forest with tall but stripped trees standing amid ash and snow. Giant sequoias, the largest and among the longest-living of trees, have historically survived these fires. Large firs, cedars, and other trees are being felled. The looping, 15-minute video is largely silent until the trees crash to the ground, shattering branches and throwing up huge clouds of ash. Some fall heavily, as we might expect, but others lightly, gently, as if with a sigh. To any lover of trees and forests, the work is deeply affecting.

Once, darkly beautiful scenes such as these—some of the static shots look like an apocalyptic variant of Ansel Adams—would have been experienced as sublime. In the current climate emergency, they are more immediately threatening: a vision of the …

September 15, 2022 – Feature

Warsaw Roundup

Ewa Borysiewicz

Poland, as the theorist Maria Janion has noted, lies East of the West and West of the East. The cognitive dissonance can sometimes manifest in a complex blend of inferiority complex and messianic pride, often expressed via tales of the nation’s suffering and past glory. The majority of post-1989 efforts to tell the nation’s history have focused on repressing “Eastern” attributes in favor of “Western,” but Russia’s war on Ukraine has seen the nation assert its solidarity with its beleaguered eastern neighbor.

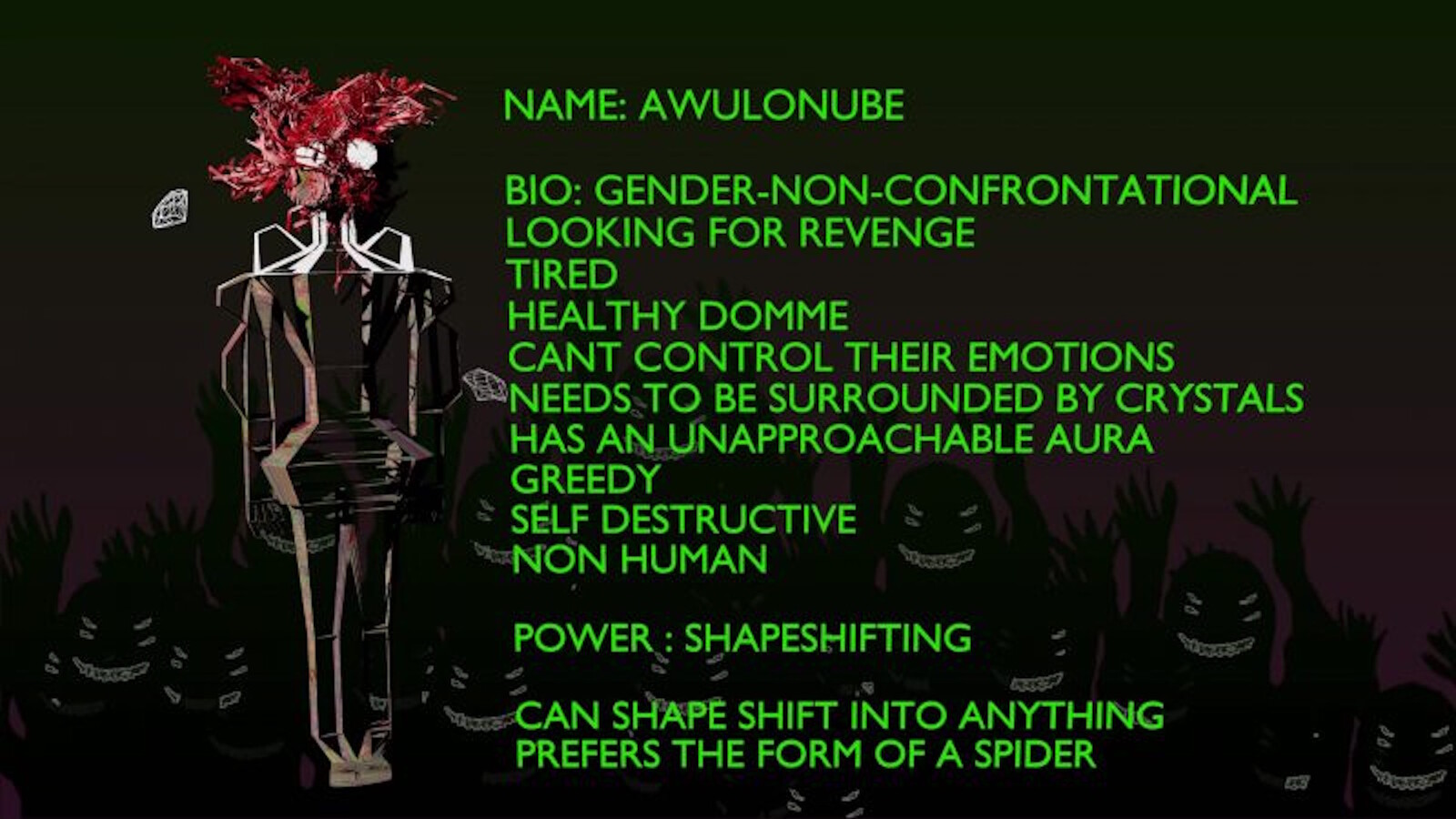

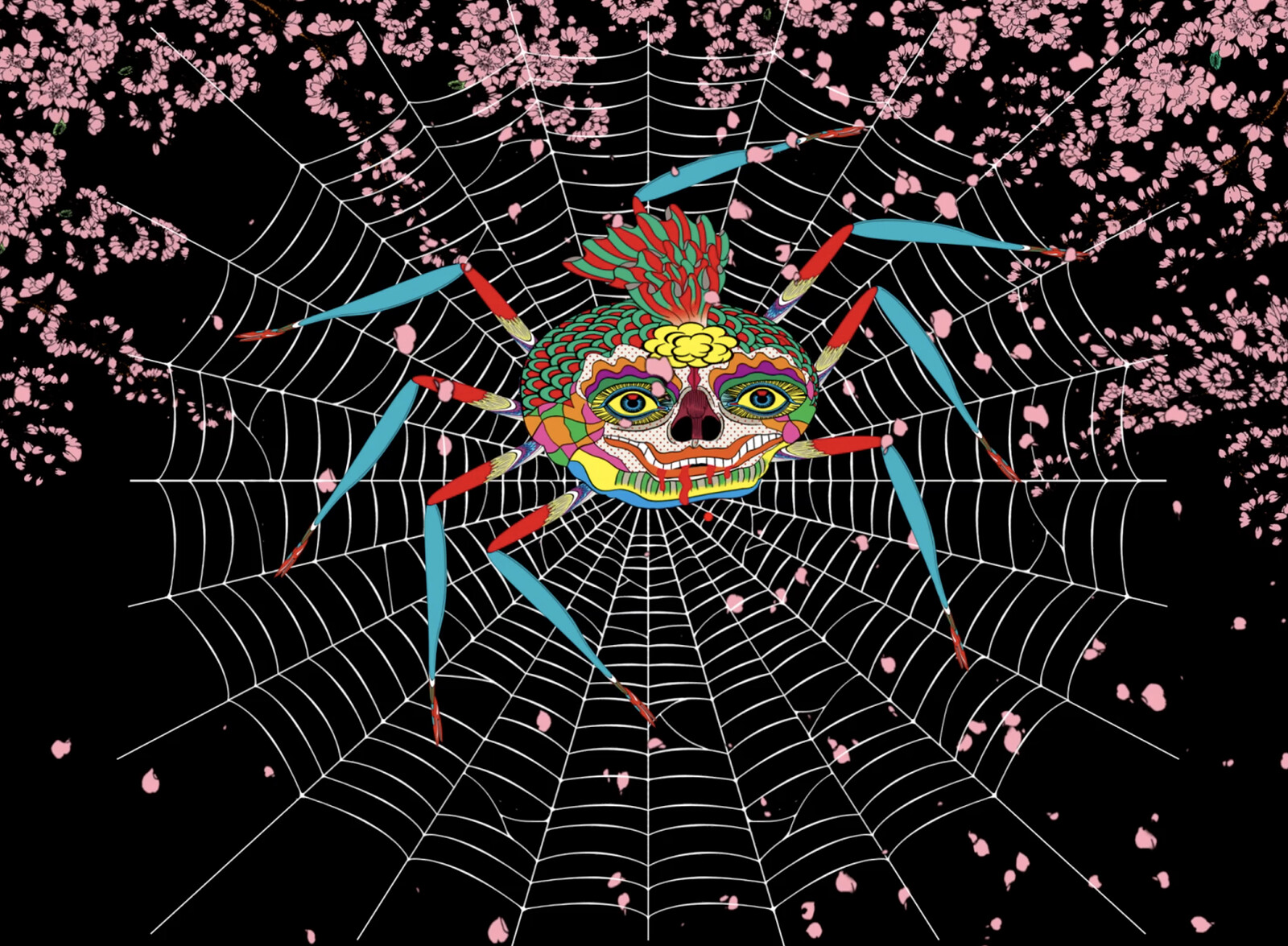

Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art is trapped between the Stalinist Palace of Culture and Science and proliferating skyscrapers, and the institution’s programming reflects the difficulty of reconciling these two influences. Its temporary home, close to the Vistula River, currently hosts “The Dark Arts: Aleksandra Waliszewska and Symbolism from the East and North,” curated by Alison M. Gingeras and Natalia Sielewicz. The reclusive painter has gained an enormous online following for her somber, cryptic gouaches depicting a cast of mysterious figures including woman-spider hybrids, sinister Slavic wraths, lonely hangmen, flayed youngsters, and bleeding mystics.

The curators have applied a decorum-defying social media logic to the show’s methodology, juxtaposing works of varying provenances and gravities. Yet the physical center of …

September 8, 2022 – Feature

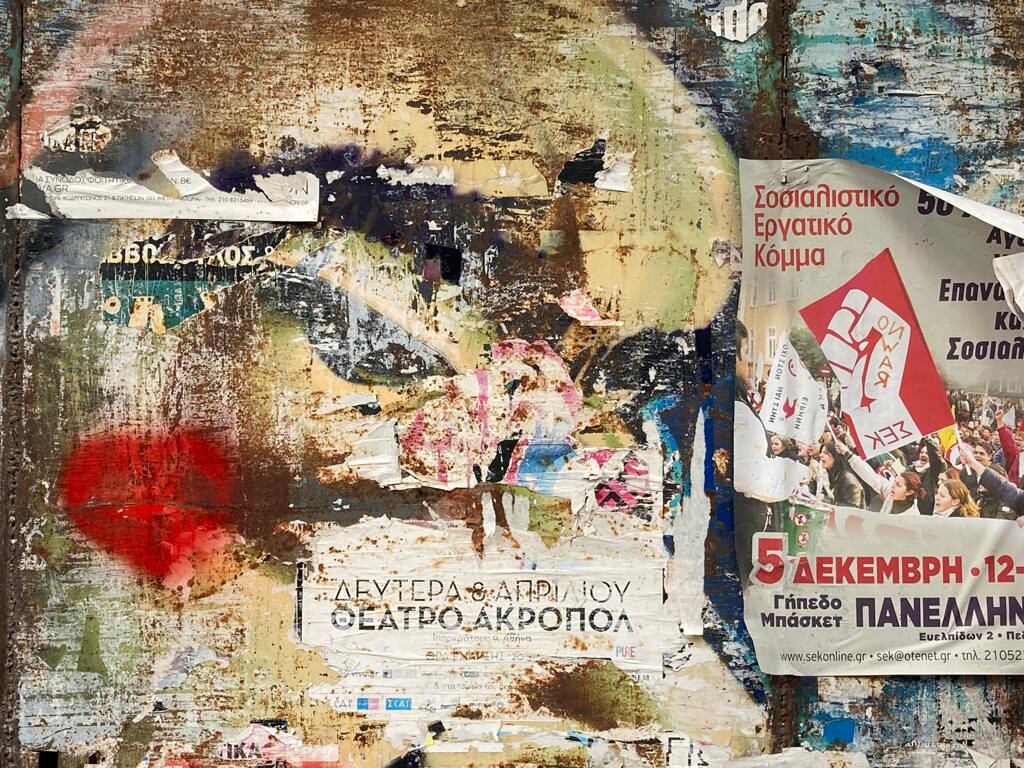

Rachel Cusk & Chris Kontos’s Marble in Metamorphosis

Aliki Panagiotopoulou

In 1894, just a year after Prime Minister Charilaos Trikoupis had declared Greece bankrupt, Athens was chosen to host the first modern Olympics. The occasion demanded the total refurbishment of the Panathenaic Stadium, a venue used for athletic competitions since ancient times. As the city embarked on this expensive endeavor, someone (the Olympic committee, mayor, or king, according to different versions of the story) posed the question “Ποιος θα πληρώσει το μάρμαρο;” [Who is going to pay for the marble?] In the decades since, the ancient Greek word has come to acquire a new significance in the modern vernacular: that of damage.

Marble in Metamorphosis, a book which “contemplates the physical and cultural life of marble,” is published by an Australian property development company active in Athens. Much like a mockup apartment, everything about this object is designed to showcase the company’s taste: an essay by Rachel Cusk, Chris Kontos’s sleek photographs of Athens and the island of Tinos, excerpts from poems by major Greek poets Giorgos Seferis and Yannis Ritsos, and a poetic afterword by Nadine Monem, all make for a chokehold of beauty. Yet, in recent years, public policies that prioritise property over home, investment over sanctuary, and …

September 6, 2022 – Feature

“That’s not it”

Daisy Hildyard

Meta is a collaboration between art-agenda and TextWork, editorial platform of the Fondation Pernod Ricard, which reflects on the relationship between artists and writers. Following on from her essay on Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster for Textwork, the novelist Daisy Hildyard considers the importance of unknowing and vulnerability in any critical response to a work of art.

There is a poem by Elizabeth Bishop about a sandpiper, a small seabird who is seen running along the shoreline, stabbing his head in the sand for grubs. On a frantic mission for food, “His beak is focussed; he is preoccupied,/ looking for something, something, something. Poor bird, he is obsessed!” This attention is sadly misplaced: Bishop’s sandpiper, in his “state of controlled panic,” is oblivious to the ocean that roars right next to him.

The sandpiper is overlaid in my mind with a passage from Virginia Woolf’s diaries in which she describes her experience as an obsessive search for something—but she doesn’t know what. “I have some restless searcher in me. Why is there not a discovery in life? Something one can lay hands on and say ‘This is it’? […] I’m looking: but that’s not it—that’s not it. What is it?” I see …

August 3, 2022 – Feature

“The double bind”: on Documenta 15

Skye Arundhati Thomas

In the third of our dispatches from Documenta 15 over the course of its 100 days, Skye Arundhati Thomas reflects on the exhibition’s foregrounding of collectives from the Global South, how this has been received, and what it might mean for the future of exhibition-making.

Collectives are often born out of necessity. In India, where I live, I see how essential communal endeavors can become: raising money for bail bonds, distributing funds for the living costs of members, building infrastructure. Collectives of this kind—often occupying a blurred borderland between activism, art, and social work—respond to a political and social alienation bred from the breakup of communities under the mechanisms of authoritarianism. In situations of near continuous emergency, and in the absence of welfare states, public funding, and institutions, the task of providing support and crisis work often falls onto individuals and their capacity to build community.

“Lumbung,” the Indonesian rice barn which serves as the curatorial proposition of ruangrupa’s Documenta 15, is a means by which to collect, store, and share resources. In keeping with that principle, theirs is a show engineered towards a relational rather than an aesthetic experience. Fourteen primary participating collectives were given €25,000 as “seed money,” …

July 15, 2022 – Feature

Reclamation in Whose Name?

Natasha Marie Llorens

“Ecological turns” is a series in which writers consider how the ecological discourse is shaping the production, exhibition, and reception of contemporary art. In this instalment, Natasha Marie Llorens reflects on a group exhibition at Palais de Tokyo which takes a “rallying cry” for a title: “Reclaim the Earth.”

Solange Pessoa’s long swaths of felted horsehair, culled and woven together over many years, are suspended from the Palais de Tokyo’s high ceilings, their rough surfaces and variegated brown tones visible from a distance as I enter the gallery. Cathedral (1990–2003) is part of a group show entitled “Reclaim the Earth,” encompassing the work of fourteen artists, conceived as a multi-generational and multi-cultural “rallying cry” in response to climate collapse. Pessoa’s references to horses imported to Brazil by the Spanish are described by the wall label as evocative of “distant memories of Brazil’s colonization by the Europeans,” and the artist’s contribution to the exhibition is summarized as animating “both living and non-living elements, mixing present time with the ancestral past.” I am attracted to the abject quality of Pessoa’s lines traced over the ghost image of Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasilia Cathedral, but I balk at the softness of the generalization “European colonization,” …

July 12, 2022 – Feature

“Shared memories”

Akin Oladimeji / Jelili Atiku

Last month the Lagos-based artist Jelili Atiku trod tenderly through a public square in London, weighed down by maquettes strapped to his feet. Small sculptures, mounted on a large cardboard box daubed with “Pfizer,” “Kano,” and “1996,” obscured his vision. The performance—titled Wórowòro, Kóbokòbo and shown as part the group exhibition “In a Pot of Hot Soup: Art and the Articulation of Politics in Nigeria” at the Brunei Gallery in the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London—was Atiku’s response to the Pfizer drug trial scandal of 1996 and its impact on our pandemic-scarred present. During that controversy, the pharmaceutical giant pledged to combat a meningitis epidemic in Kano, northern Nigeria, by trialling a new drug on 200 infected children, leaving eleven dead and dozens more injured.

Atiku’s work across drawing, multimedia installation, and performance combines Yoruba performance traditions with political activism to address subjects including human rights abuses and postcolonial trauma, at times with the intention of directly provoking political change. In 2016, he was arrested in Ejigbo, Lagos, on charges of “public disturbance and inciting the public” over his performance work Aragamago Will Rid this Land of Terrorism. The piece, which invoked Yoruba …

July 8, 2022 – Feature

“Towards Life”

Chus Martínez

Meta is a collaboration between art-agenda and TextWork, editorial platform of the Fondation Pernod Ricard, which reflects on the relationship between artists and writers. In her essay on the work of Martine Aballéa for Textwork, Chus Martínez considered how its new “ways of sensing” the world might suggest new ways of acting within it. This curiosity about how other consciousnesses—human and nonhuman—construct their surroundings also characterizes Martínez’s work as artistic director of TBA21–Academy’s Ocean Space in Venice, which is dedicated to improving our understanding of the oceans through art, and as director of the Art Institute at the FHNW Academy of Art and Design in Basel. This conversation picks up threads from that text, ranging from what it means to think of art as a living being to why she retains “the highest respect for joy.”

art-agenda: You write beautifully of how reality is constructed by our sensory faculties: so the world as inhabited by a human does not only look different but is different to the world inhabited by, to take your example, a turtle. How can art help us to reconstruct the world?

Chus Martínez: I am always fascinated by how we fantasize: how fantasy allows the human …

July 1, 2022 – Feature

Natasha Soobramanien & Luke Williams’s Diego Garcia

Orit Gat

The narrator of Diego Garcia, a novel written collaboratively by Natasha Soobramanien and Luke Williams, is sometimes a he, sometimes a she, always a we. When its two speakers, Oliver and Damaris, are not together, the narrative can fracture into separate columns. They live in Edinburgh. It’s 2014. “We” walk to the library; “he” makes coffee in the morning; “she” loves the cardamom buns at the Swedish café. The city is a backdrop to their conversations about Theodor Adorno and James Baldwin, the Velvet Underground, writing, and money; they discuss their debts in numbers, their credit scores in terms of unavailable futures. On the streets are posters for the Scottish Independence referendum.

Their life feels detached until one day they meet Diego. Diego is Chagossian, from the community exiled to Mauritius and the Seychelles by the British government between 1967 and 1973 so that the island of Diego Garcia could be turned into a US military base. Diego—the name he adopted in acknowledgement of his lost homeland—meets them one night for a drink. They never see Diego again, but before he leaves he tells Damaris his life story: how he grew up in Mauritius and ended up undocumented in the …

June 29, 2022 – Feature

“Contested Histories”: on Documenta 15

Jörg Heiser

In the second of our dispatches from Documenta 15 over the course of its 100 days, Jörg Heiser considers the row over anti-Semitic content that erupted shortly after the exhibition’s opening.