Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

June 28, 2021 – Feature

London Roundup

Orit Gat

It would be impossible to think about London’s first Gallery Weekend in early June outside the context of the slow re-emergence from lockdowns. I know this strange sensation is not unique, but the experience of a public disaster dealt with largely by isolating from society has also marked the way I look at art. Taking stock of my tour of the city, it strikes me that the artworks which affected me most were ones that displayed intimacy, proximity, and all those daily exchanges from which I have felt distant these past sixteen months.

That is not to say that the daily and intimate are not political. At Lisson, “An Infinity of Traces,” a group show curated by Ekow Eshun, focused on the work of UK-based Black artists. It included Alberta Whittle’s video Between a Whisper and a Cry (2019), which explores Barbadian poet and historian Kamau Brathwaite’s idea of an oceanic worldview in the aftermath of the Middle Passage, and a series of watercolor text drawings by Jade Montserrat (who also has a solo show at Bosse & Baum in South London) that bear heavy, physical messages, like The smell of her still burning hair (2017). When I was trying to …

May 10, 2021 – Review

John Akomfrah’s “The Unintended Beauty of Disaster”

Cora Gilroy-Ware

Viral videos, especially those featuring animals, rarely make a lasting impression. Part of their charm is their innate forgettability. But every now and then there is an exception. In April I came across a video online that has haunted me ever since. Shot by drone from directly above, this 49-second clip centers on a strange spiral made up of hundreds of tiny gray-brown forms moving clockwise over a pale surface. As the camera moves down, we see that these forms are four-legged creatures whose fur ranges from dark taupe to a white brighter than what gradually reveals itself to be snow under their hooves. When the camera retreats back up into the sky, we glimpse another, more dense and fast-paced spiral to the left. A caption states that these are “reindeer cyclones” captured on the Kola Peninsula, the north-eastern part of the area known as the Baltic Shield. Responding to an outside threat, reindeer gather and move in a whorl, keeping their fawns tucked safely in the middle. In the comments under the post, viewers asked what, in this instance, caused the reindeer to behave in this way. “Probably the drone” was the consensus.

Not only were these mesmerizing rosettes …

April 10, 2018 – Review

Laure Prouvost

Alan Gilbert

Eager to see the art in Laure Prouvost’s first solo exhibition at Lisson Gallery in New York, visitors might breeze through its central installation: Uncle’s Travel Agency Franchise, Deep Travel Ink. NYC (2016–18). Situated at the entrance to the gallery, it looks like an unkempt and outdated version of an art gallery’s normally pristine front desk featuring a guest book, a stack of press releases, and a 3-ring binder containing an artist’s curriculum vitae and relevant press materials. Instead, Prouvost has surrounded the gallery attendant with promotional airline posters, maps, a bookshelf lined with travel guides, a coat rack and umbrella stand, an outmoded printer, a dirty water cooler, and even the requisite framed family photo on the desk. To the right of this configuration is a table with two chairs and a ceramic teapot in the shape of a pair of buttocks that is the first explicit clue to the whimsy and weirdness of Prouvost’s art.

The exhibition’s conceit is that all the work on display—including installation, sculpture, painting, textile, and video—is connected to this travel agency. Three other workstations feature stacks of plane-ticket receipts and travel magazines with the company name, “Deep Travel Ink,” printed on white labels affixed …

January 9, 2017 – Review

Wael Shawky

Ilaria Bombelli

Craggy peaks of stone, desolate plains, parched and rasping arctic coasts—still caught perhaps in some distant geologic era—provide a home to stray beasts of all kinds: the spindly heads of snakes rise like pinnacles from the summits of crumbling towers. The sagging legs of pachyderms prop up arcades redolent of Byzantium. The hooked beaks of hawks frown from the prows of merchant vessels. Prehistoric herbivores with dorsal crests like minarets spring from the ground, breaking its crust as if they had just awoken from centuries of hibernation. The salt spume curls into the outline of a feather, of a scale. Stone turns to visage, snout, and sneer.

Pinned down by tremulous lines of ink and graphite, and filled with the pale colors of a sorbet—blush, ocher, powder blue—the drawings of surreal vistas (about 20 in all, with the collective title Al Araba Al Madfuna Drawings, 2015) that underpin Wael Shawky’s first show at Lisson Gallery’s Milan venue tell of a world straddling past and present, East and West, with the penchant for zoomorphism found in ancient civilizations, first and foremost that of Egypt, the artist’s home country. Docile creatures parade through them, alarming no one. The doubtful perspective skews planes and …

July 26, 2016 – Review

John Akomfrah

Andrew Stefan Weiner

It is lamentable and somewhat curious that John Akomfrah is just now receiving his first major exhibition in the US. Despite the critical acclaim Akomfrah has received in the UK and Europe, both for his recent solo output and his earlier work with the Black Audio Film Collective, he remains relatively unknown to Americans outside the experimental film community. One hopes that the current show at Lisson Gallery’s new Chelsea outpost will begin to address this oversight, thereby bringing more attention to the pivotal, underexposed history of Black British cultural production in the Thatcher era and to its continuing relevance in the present.

Responding to the precedent of Third Cinema, as well as the thinking of figures including Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy, groups like BAFC and Sankofa Film and Video Collective (which included Isaac Julien) used broadcast media to advance a nuanced critique of the intersections between race, neoliberalism, and postcoloniality. Rethinking the politics of the African diaspora through the idiom of emergent artistic, musical, and mediatic forms, these cooperatives laid the foundation for what would later be called Afrofuturism, establishing a crucial precedent for contemporary practices like those of the Otolith Group and Chimurenga. Perhaps the most outstanding example …

February 18, 2013 – Review

Gerard Byrne’s “Present Continuous Past”

Gil Leung

To adequately reflect on the present moment requires a certain distance, some way of pulling out of the perpetual now of contemporary time and into another. This phenomenon can be evidenced in the compression of time that occurs when attempting to recall the near past; years turn into events and decades into fashions. Hindsight, as this is usually referred to, posits the notion of an ability to see something clearer from further away, from a distance. Gerard Byrne’s “Present Continuous Past” is not about the accuracy of a past represented so much as an attempt to collapse and flatten one differentiated temporality into another. The show itself is framed as an accompaniment to Byrne’s current survey exhibition “A state of neutral pleasure” at Whitechapel Gallery.

In its most literal sense, “hindsight” would imply seeing the back of something, the behind. Byrne’s 2013 series of silver gelatin prints—such as Inventory number 3280, a depiction of the martyrdom of St. Quirinus, photographed in the Belvedere Museum, Vienna, 219 years after it was painted, and reproduced here at 68% of its original size—depict the backs of framed canvases, in a continued reference to Cornelius Gijsbrechts’s 1670 trompe-l’œil Reverse Side of a Painting, the back …

June 24, 2011 – Review

Ai Weiwei

Filipa Ramos

Be it tax evasion or political activism with excessive media, or the former that makes the perfect bait for the latter, it will be hard to tell. What is certain is that artist Ai Weiwei was released on bail by the Chinese police after being arrested and detained without access to his lawyer for some eighty days.

Under these circumstances, what can be said about another exhibition of Ai Weiwei that does not risk turning recent reactions to the artist’s arrest into banal manoeuvres deprived of potency to incite action? Can we ask this of ourselves without sounding cynical?

It is a delicate situation, and we are well aware that the recent exhibitions of Ai Weiwei’s work no doubt solidified his relevance as an artist; even so, a rather disenchanted perspective hovers over recent events, which could be perceived as a shadow of opportunism trailing the increase of interest in the artist.

Ai Weiwei was omnipresent during the opening of the Venice Biennial: one of the texts of its official catalogue bears the title “Where is Ai Weiwei”—a diffuse slogan which has become a mute motto to reaffirm the pressure for justice. And words were not the only weapon, as many wore a …

January 7, 2011 – Review

Ceal Floyer at Lisson Gallery, London

JJ Charlesworth

There’s a kind of neo-conceptualism that loves puns. After all, it was old-style conceptualism that first sternly denounced the usually invisible join between object, language, and concept, but that was only on the back of the dry wit of conceptualism’s own errant uncle, Marcel Duchamp, who, unlike his dour descendants, couldn’t resist the ludic anarchism of wordplay and wayward signification. In the middle of winter, you’re always forced to smile at Duchamp’s snow shovel, In Advance of the Broken Arm (1915).

Ceal Floyer is member of the school of neo-conceptualist absurdism, and part of a self-consciously self-deprecating and quotidian strand of post-90s British art that, along with contemporaries such as Martin Creed or Jonathan Monk, reworked the lessons of conceptualism, while re-grounding it in the cheerfully humdrum experiences of the everyday.

Here Floyer keeps things colorless, using the aesthetic negative of conceptualist monochrome against the often bad-pun levity of her linguistic short-circuits. So Ladder (minus 2-8) (2010) is a standard aluminium house ladder with every rung removed except its first and ninth step. It might as well be titled In Advance of the Broken Leg, but it serves as a quick-fire assertion of Floyer’s interest in how minor gestures carried out on …

July 12, 2010 – Review

Rodney Graham’s "Painter, Poet, Lighthouse Keeper" at Lisson Gallery, London

Tyler Coburn

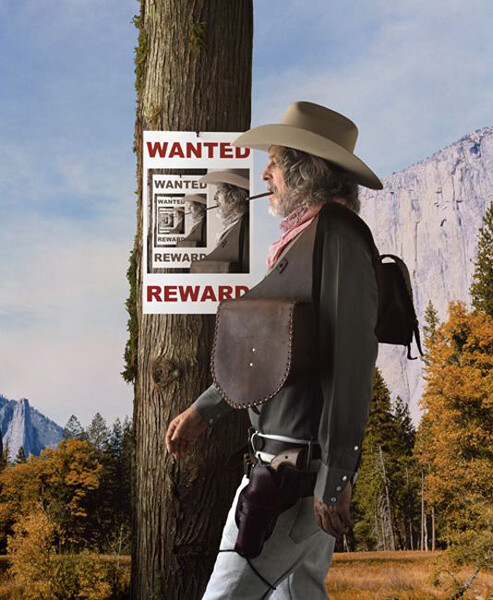

Since first stepping onto the other side of the lens in the mid-90s, Rodney Graham has fashioned himself as all color of amateur and outlaw in a wry game of wish fulfillment for an artist of inescapable renown. Cowboys, pirates, saloon men, and Sunday painters, these pseudo-egos follow the performative loops of their respective genres in films and lightboxes that Graham—the consummate citationist—appends with still other pop-cultural and esoteric references. Such densely layered work can make for stimulating (if maddening) viewing, much as Graham’s repeat billing can tilt from artistic reflexivity to self-infatuation. But if the trickster artist’s practice explores the innumerable ways that cultural history can be reframed, then any complaints about his ubiquity falter at the possibility that, like the mise-en-abîme of a wanted poster in Paradoxical Western Scene (2006), one frame merely invites another.

“Painter, Poet, Lighthouse Keeper,” the title of Graham’s current exhibition at Lisson Gallery, introduces several new characters whose creative lives are deeply marked by history. The lightbox Lighthouse Keeper with Lighthouse Model, 1955 (2010) depicts the lighthouse keeper in his maritime kitchen, at a time when automation was rendering his job redundant. Graham’s protagonist instead continues his work on a miniature-scale: a model of …