Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

February 23, 2023 – Review

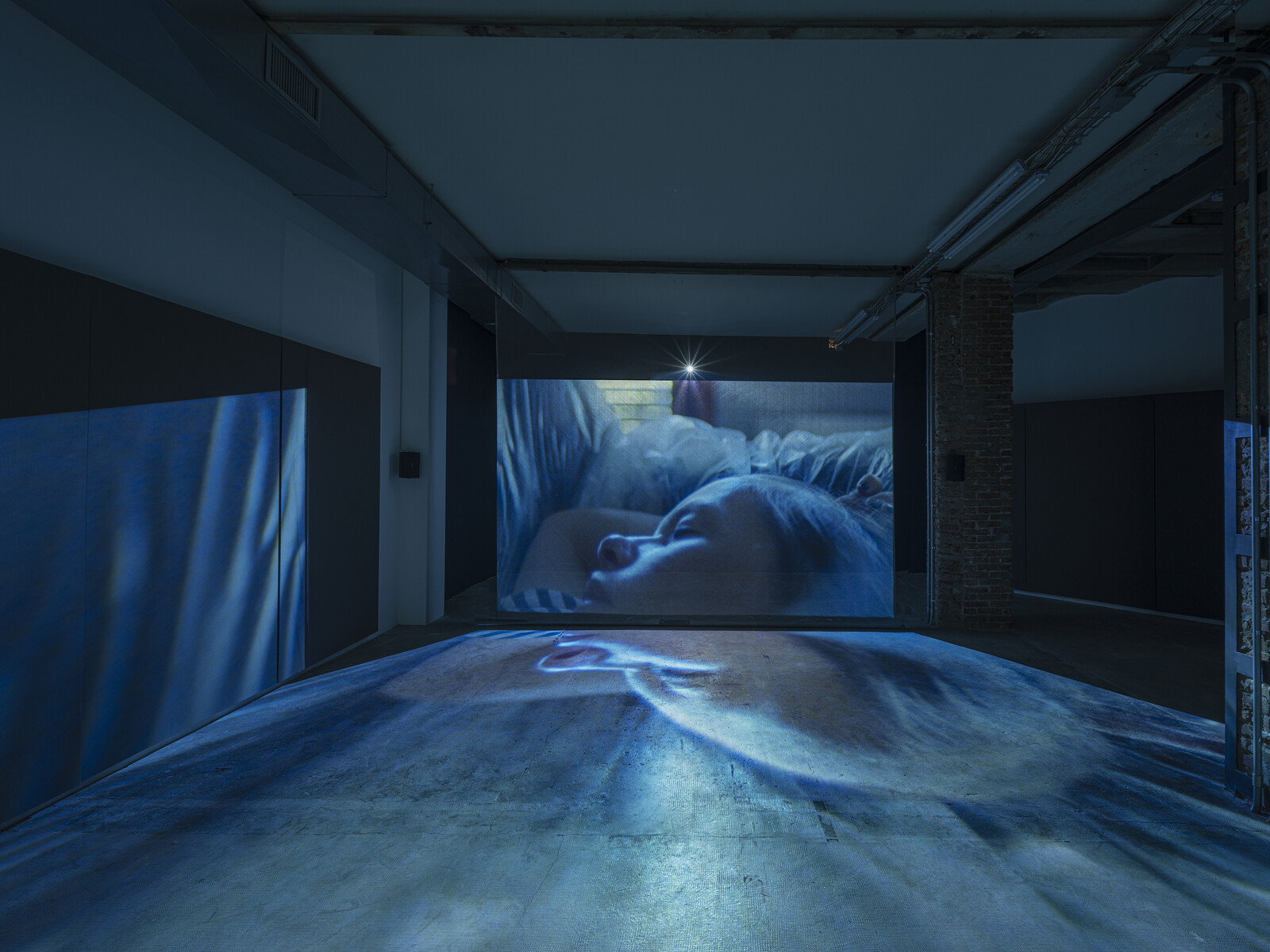

Beatrice Gibson’s “Dream Gossip”

Juliet Jacques

Beatrice Gibson’s first solo exhibition in Italy takes its title from Alice Notley’s column in the self-published 1990s New York zine Scarlet. In the column, Notley invited readers to transcribe their dreams, printing them alongside articles, poetry, and editorials about the AIDS crisis and the Gulf War, sharing with the Surrealists a feeling that dreams were both aesthetically striking and politically potent.

Gibson’s response to Notley’s work includes three films. Ordet’s main space is dominated by the newest, Dreaming Alcestis (2022), in which Euripides’ heroine inspires a portrayal of the process of dreaming, and how external stimuli, experienced by day or night, shape the unconscious imagination. In Dear Barbara, Bette, Nina—a four-minute work made in Palermo in 2020 and presented on a small monitor, with headphones, to one side of the room—Gibson reads from a phone a letter to three older women filmmakers over a shot of her hands at rest. Deux Sœurs Qui Ne Sont Pas Sœurs [Two Sisters Who Are Not Sisters] (2019), loosely adapted from a Gertrude Stein screenplay written in 1929, is shown on a large screen in its own room. It provides a collective portrait of Gibson’s influences, friends, and collaborators—including Notley herself—in a time …

May 6, 2022 – Review

Elmgreen & Dragset’s “Useless Bodies?”

Cathryn Drake

The sleek, sardonic work of Scandinavian duo Elmgreen & Dragset has found a consummate context in the Fondazione Prada, a private museum founded by luxury fashion entrepreneurs. The question mark in the exhibition title—“Useless Bodies?”—signals an interrogation of the human body as a viable organ in contemporary society, played out within the context of a western-centric ideal of beauty and vitality.

The main space, called the Podium and employed in all the term’s senses of stage, soapbox, and platform, is arrayed with human figures engaged in related but disassociated activities. Classical marble nudes—tautly muscled athletes, a young shepherd with a dog, and a reclining gladiator among them—mingle with bronze sculptures of pubescent boys to suggest a diorama in an archaeological museum. The only woman represented is Pregnant White Maid (2017), regarding a petulant, pouting schoolboy (Invisible, 2017) with her eyes decidedly shut. All of the contemporary bronze figures are lacquered in opaque white or buffed to a brilliant glow, with the exception of a striking black Runner, from the first century BC, idealized with Caucasian features and a startlingly realistic gaze.

Like a terrarium, the main space is transparent yet hermetic, enhancing a sense of highly visible isolation, not …

April 13, 2021 – Review

Kasper Bosmans’s “A Perfect Shop-Front”

Francesco Tenaglia

Kasper Bosmans has turned the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro outside in. On entering his solo exhibition, the visitor is presented with a reproduction of a stylized city: painted onto the walls in shades of red are two ajar doors; assorted memorabilia can be glimpsed through a window display; a mural resembles a fake stone wall; and a thin pink highway painted on the floor, beside which rests an object resembling a discarded necklace, directs the viewer to a red wall on which hang three paintings the size of standard letter paper. Curator Eva Fabbris approached Bosmans about a show before the pandemic. The project morphed over the following months to suit the radically changing conditions, and to reflect art institutions’ ongoing anxiety over how they relate to their audiences. “A Perfect Shop-Front” could be thought of as a kind of trompe l’oeil: the minimal rendering of an urban project within an institution. A tiny strip of the city has percolated into an exhibition space, creating a zone of thresholds in which the boundaries between inside and outside are thin.

A serendipitous detail: Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro is located just a few steps from Milan’s Navigli, two artificial water channels built in the …

July 10, 2020 – Review

Trisha Baga’s “the eye, the eye and the ear”

Francesco Tenaglia

Contrary to the press materials for Trisha Baga’s “the eye, the eye and the ear,” which liken the presentation to that of a natural history museum, the New York-based artist’s first institutional exhibition in Italy recalls the Egyptian Theater fad of golden-age Hollywood. A procession of “Hypothetical Artifacts” (2015–20), a series of ceramics sculptures precisely arranged on a plinth that zig-zags like a snake, offer the first hint of an architectural craze that followed the 1922 discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb. In this “geological corridor of evolution,” as the artist describes it, everyday objects such as picture frames, a printer, and a microscope are rendered like fossilized movie props. Several of these pieces appear in video installations positioned around the darkened gallery. Spot-lit and decorated with plants, lamps, furniture, and other items, the installations resemble sets on a soundstage.

The “Hypothetical Artifacts” are displayed to one side of the dark, majestic spaces of Pirelli Hangar Bicocca—a cathedral-like black box both geographically and architecturally opposed to the light-flooded, neo-Renaissance Prada Foundation citadel on the other side of Milan. Nearby, another group from the same series—ceramic poodle heads resembling flame-topped Sphinxes—are placed on a pyramidal plinth. Both display surfaces bring to mind the …

January 16, 2018 – Review

Gerasimos Floratos’s “Soft Bone Journey”

Ilaria Bombelli

As you walk up to Armada—through a courtyard ringed with industrial sheds and machine shops—placards appear to the right and left that read “adagio” (“drive slowly”), “non urtare” (“caution”), and again, “adagio.” Even if you aren’t the size of a truck, these signs have a way of making you proceed carefully, tentatively. As if moving through some large, lethargic organism. Armada is a former warehouse on the northern edge of Milan, converted into an artist-run space in 2013. The name brings to mind the fleet of Philip II, though there doesn’t seem to be any real connection. Except insofar as it’s managed by a crew of about 20 young people, with a range of artistic aspirations. What they all have in common is the experience of having studied at the Brera Academy under Alberto Garutti, a great figure in Italian public art whose presence can be felt here—the courtyard even contains a plaque with “Garutti” and a notice above it: “reserved, no parking.” His studio is close by.

Gerasimos Floratos’s solo show at Armada, “Soft Bone Journey,” is comprised of three large paintings in oil and acrylic, and three sculptures, each the size of a person, made of painted styrofoam. (All …

September 5, 2017 – Review

“The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied.”

Erika Balsom

THE BOAT

The metaphor of the ship of state is best known from Plato’s Republic. In the “collective exhibition concept” developed by Udo Kittelmann for the Fondazione Prada, this maritime trope of political community is evoked unmistakably yet only obliquely, mediated through the titular citation of Leonard Cohen’s devastating 1988 song “Everybody Knows.” Ancient foundations meet our contemporary crisis in a palimpsestic detour perfectly befitting this brilliant, bewildering, and highly intertextual exhibition. Across three floors, Kittelmann interweaves the work of three German artists, each preeminent in their respective field, each with a distinct interest in the politics of illusion and the textures of modern experience: photographer Thomas Demand, filmmaker Alexander Kluge, and scenographer Anna Viebrock. The result is less an experience of disparate practices, let alone single artworks, than it is an encounter with a holistic, albeit fragmentary, reflection on truth, falsity, and the public sphere in an age of “alternative facts.”

If the political community is a ship, this vessel is our quotidian domicile. Yet the ship is also a heterotopia—a space with its own time, its own rules. Inside Prada’s baroque palazzo—itself set apart from the tourist bustle—Viebrock has meticulously recreated an array of such “other spaces”: a …

July 13, 2017 – Review

Mandla Reuter

Ilaria Bombelli

The invitation to the third solo show by Mandla Reuter at Francesca Minini bears no title or explanation. It relies on just one image, evocative enough on its own: a moonless sea, rippled by waves. Even the press release, stripped of all syntax, is reduced to a chain of words that hint at some meaning but mostly conjure a mood. They include “water,” “island,” “forest,” “sewage,” “dusk,” “stamp,” ”chocolate,” and “remnants,” plus geographic locations, names of cities, and numerical measurements. So we visit the exhibition with this sea in our heads, so to speak, and a few inorganic clues.

At the entrance, the exotic image of a bronze cocoa pod (Cacao, 2017), along with other specimens still nestled within their plaster molds, summons all the various things associated with this fruit (prosperity, exploitation, luxury, poverty, etc.). The viewer’s gaze is immediately drawn—with the sense of the sea growing stronger—to a huge salvage airbag (its crate also exhibited nearby) whose hyperbolic bulk fills and almost seals off the gallery. This sort of obstruction is not a new device for the artist, who in the past has blocked gallery entrances with boulders so that visitors had to strain for a glimpse of the …

March 14, 2017 – Review

“Neon Paradise: Shamanism from Central Asia”

Ilaria Bombelli

One clean cut and—snip!—the plait of hair flops to the floor. Then comes the next braid—snip!—and the next—snip-snip! Strand by strand, all the remaining black hair of this Asian woman, dressed in traditional Kyrgyz garb, is sheared off by her own hand. It falls around her feet, leaving her neck bare. A black screen. The video starts over. We see the same woman again, now plucking the strings of an ancient instrument called the kyl kyyak, while a man braids the same long hair that will soon fall prey to her scissors. Around them, a swarm of people—random visitors to a museum in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan—gape at the scene.

“This video/performance from 2001, titled Farewell Song, was inspired by an age-old custom in Kyrgyzstan, where women are supposed to let their hair grow until it is plaited into very thin braids for their wedding,” the gallery assistant tells me. “And so the scissors are symbolically severing all ties with a past that is felt to be stifling, in order to bid it farewell.” The artist seen here is Gulnara Kasmalieva, who along with with Muratbek Djumaliev (both live in Bishkek) seems to use the act of cutting (a leave-taking, a departure) as …

March 16, 2016 – Review

Allison Katz’s “AKA”

Ilaria Bombelli

“Rats live on no evil star.” And “In a regal age ran I.” There is no apparent truth, no evident foundation, in these two double-sided expressions—same characters, reverse order—whose heads and tails can switch places like a juggler’s pins. Just a tumbling act of letters on the tightrope of some semblance of meaning, found in those special words or phrases that can be read from left to right or right to left without a hitch, through a simple mechanism properly termed a palindrome—from the Greek palindromos, “running back again,” like a crab, after it runs forward.

Montreal-born, London-based Allison Katz is a true virtuoso of the genre, to the point that she’s titled her first exhibition with Giò Marconi in Milan “AKA”—a palindromic acronym that naturally stands for “also known as,” but which takes on a broader scope here with its almost obligatory hint at the initials “Allison-Katz-Allison.” Linguistic and phonetic associations do seem to whet the appetite of this Canadian artist, who also played with the sound of her first name in the title of her most recent solo show at Kunstverein Freiburg, “All Is On” (All-is-on), to which the show at Giò Marconi acts as a sort of postscript, …

April 16, 2015 – Review

Nicolas Party’s “Two Naked Women”

Ilaria Bombelli

Standing knee-deep in brackish water as dark as iodine, two stocky women, closely resembling each other and completely naked, have their backs turned to us. Their arms hang slack along their sides in a very relaxed pose that wraps their bones in unmoving shadow and highlights their mature, voluptuous buttocks, firm and knobby as quinces. Their hair is gathered into buns pinned at the nape of their necks, their gazes fixed on a secret, private, unknowable landscape. They are unquestionably unconcerned with reality.

Aloof and absorbed in their own leisure, the two modest bathers that Nicolas Party has drawn in charcoal on the white-plastered walls of the kaufmann repetto gallery, in a style evocative of Guercino or a certain vein of nineteenth-century painting, are the nude horizon for the first solo show by this Brussels-based Swiss artist—appropriately titled “Two Naked Women.” These portraits function as a sort of classical, nostalgic backdrop, which imbues the about fifteen works on view with a rarefied, languorous mood, warding off any impatience or haste. These works are for the most part pastel on canvas (all dated 2015, and of slow gestation), whose literal titles—Portrait, Still Life, Landscape—betray a keen interest in certain tropes and stylistic …

January 12, 2015 – Review

Marvin Gaye Chetwynd’s “Bat Opera 2”

Barbara Casavecchia

“And here Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying to herself, in a dreamy sort of way, ‘Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?’ and sometimes, ‘Do bats eat cats?’ for, you see, as she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way she put it.” Adventures in Wonderland, cats and bats—or bisky bats and pussy cats, one could say, to quote from Edward Lear, another Victorian genius of rhyme—abound in Marvin Gaye Chetwynd’s exhibition at Massimo De Carlo, Milan. This exercise in small surprises, hazy colors, odd creatures, and pensive stupor is the final chapter of an intense year of work for Chetwynd, marked by her first solo exhibition in a British institution (Nottingham Contemporary) and two others in London (at Sadie Coles and Studio Voltaire), besides other projects in France, Scotland, Poland, Austria, Australia, and the U.S. No performance was attached to this Milanese stop (while in 2008, for her debut at the gallery, Chetwynd orchestrated a frenzied Snail Race, with two teams of dressed-up contestants riding giant shells) and yet, despite the absence of live bodies and action, the artist is present.

Everything is overtly DIY, analog, hand-made. Chetwynd uses poor materials …

November 3, 2014 – Review

Keren Cytter

Barbara Casavecchia

Keren Cytter hypnotized me twice in the past few weeks. And I liked it. The first time was in London, where her audio piece Constant State of Grace (2014) was installed in a busy corridor at Frieze Art Fair. Headset on, I was asked by a robotic voiceover to let go, to embrace the fact that someone or something else was “taking over,” and to “overcome [my] feelings”—of being lost in the supermarket, in my case. Combined with an acoustic loop of binaural beats, which stimulate brain waves to induce relaxation and meditation, the voice instructed me, instead, to enjoy the “smiling faces” and “foreign landscapes” of the fair: a soothing, creepy, and hilarious antidote to the cupio dissolvi [wish to be dissolved] in the surrounding sea of consumption.

It happened again at the artist’s second solo show at Galleria Raffaella Cortese in Milan, when I sat alone in front of Cytter’s latest video, Ocean (2014). Watching alone was not a personal choice: the work, displayed on a monitor, includes only one set of headphones and one office chair, so intimacy is coerced from its viewers. This prescriptive one-to-one condition recalls the setting of a therapy session, or one of our …

July 2, 2014 – Review

Trisha Baga’s “Free Internet”

Barbara Casavecchia

“Free Internet,” Trisha Baga’s exhibition at Giò Marconi, is a scrappy, energetic, stoned out tour de force in visual stimulation. Behind 3D glasses, your eyes have to move fast in order to focus on her continuous ping-pong of vacillating images: floating slices of salami, overlapping images, bats in caves, cats at night, partying animals, icons jumping at you, and internet search results with keywords like, “where is my vagina?”—which immediately reminded me of artist Nam June Paik’s 1962 hand-scrawled composition Danger Music for Dick Higgins: “Creep into the VAGINA of a living WHALE.”(1) Sounds, glitches, radio feeds, samples of laughter, and songs contribute to the work’s overall synesthesia. It’s like browsing through a chronology of fragments of “reality,” or whatever that means in the age of the Oculus Rift.

And indeed, once inside the show, “Is this real?” becomes a persistent question. This must be—to borrow the term from art historian Michael Baxandall—our “period eye.” Baxandall first introduced this term in 1972 to characterize the impact of cultural factors on our ways of processing visual data and understanding pictures.(2) He argued, for instance, that during the Renaissance both painters and public embraced geometric perspective at a time when merchants and bankers …

March 31, 2014 – Review

Milan Round Up

Barbara Casavecchia

A spotlight can transform quite a bit with an economy of means, making something instantly visible, no matter how small or familiar. Post-winter sunlight can achieve a similar effect, which is why “The Spring Awakening” was an apt title choice for the program of exhibitions, openings, and performances organized around this year’s miart fair. Although everything under its purview was already on the urban map, miart’s new ventures made the local network of artists, institutions, and galleries look fresher and more energetic, signaling a positive shift within the cultural sphere. Milan’s contemporary art scene seems to be finally catching up with the success of the city’s annual furnishing design bash Salone Internazionale del Mobile, perhaps by emulating its three-part format: a serious fair to busy one’s self for half the day; a range of things to see about town for the other half; and a wide array of social gatherings.

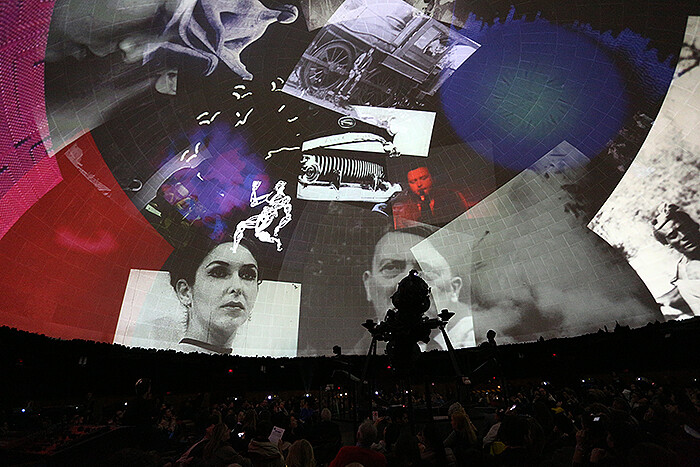

On Friday night at 1 a.m., when I stopped by at the Ulrico Hoepli Planetarium to see Stan VanDerBeek’s Cine Dreams: Future Cinema of The Mind (1972/2014)—an immersive installation of over 50 16mm films and slide projections presented for the first time in its entirety since its premiere—the queue outside …

March 28, 2014 – Review

miart 2014

Filipa Ramos

Milan, a city that cultivates its world-famous reputation as the capital of fashion and design, is currently taking big steps to relaunch its identity as a center for artistic production, and miart, its two-year-old upstart art fair, has been playing an essential role in this reinvention. With its access-controlled, rational grid plan, the fair’s architecture gives the impression of visiting a city within a city; its perfectly linear alleyways intersecting other equally perfect linear alleyways, its circulation system and signs, its various accommodation settings and meeting points, and its diverse sectors allow one to reflect on miart’s own relationship to the revamping of Milan’s cultural politics. The fair’s unavoidable sprawl is replete with a gentrified center where the old meets the new, and traditional, conservative enclaves meet newly developed areas.

The fact that miart is on a vastly smaller scale than the city of Milan itself—one that can be traversed and observed in a couple of hours—makes it an optimal site for testing out a paradigm of vision Irish writer and artist Brian O’Doherty conceived in close connection to contemporary art. O’Doherty’s “vernacular glance” refers to the fast mode of attention by which we process the city’s overwhelming multitude of visual …

January 21, 2014 – Review

Thea Djordjadze’s “Oxymoron Grey”

Federico Florian

The raw material of Thea Djordjadze’s work is memory—of past times, faraway places, and emotions. “Oxymoron Grey”—her new (and second) solo show at Milan’s kaufmann repetto gallery—seems to illustrate this idea entirely and intimately. The exhibition’s title may allude to the “oxymoronic” nature of her art, which hovers between painting and sculpture, completeness and fragmentation, materiality and pure energy. Much like her sculptures, grey is the hue of what is vague, undefinable. It is also the color of the cold Soviet buildings in Georgia, which are vividly engrained in the memory of the artist, who was born in Tbilisi and now lives in Berlin.

The first room hosts a delicate, elegant composition of sculptures and wall assemblages. In its form, the installation recalls a bedroom, or rather the “essence” of a bedroom. Two squared, steel beds (the small one perhaps the prototype of a crib) lie on the floor, beside an odd coat rack rendered in a pseudo-Bauhaus style; hung on the walls are a series of painted, cut rugs, a blue, varnished shelf-like box, and a kind of abstract tableau made with polished steel, clay, and paper maché. This last one—called Untitled (2013), like all the other pieces on show—is …

November 4, 2013 – Review

João Maria Gusmão & Pedro Paiva’s "Onça Geométrica"

Barbara Casavecchia

There is an expression I learned as a child when I took my first English classes that never stopped generating sequences of absurdist pictures in my mind: “Not enough room to swing a cat.” Over and over again, I imagine the cat, the swing, and the room in variable combinations and sizes, all enmeshed in an improbable ménage à trois. None of them can be verified, nor tested in reality: to me, they are pure mental imagery. Strangely enough, the artistic duo João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva reactivated my odd, feline-generating imagination with their eerie short story about swinging a cat out of a room. In fact it functions as the introductory text for their current exhibition at Galleria Zero, which serves as a kind of precursor to their upcoming solo show at HangarBicocca in Milan next year.

Part of the story goes like this: “This particular incident is related to another artistic achievement from the Portuguese duo, when Paiva and Gusmão had a studio on a 3rd floor apartment they started resenting the constant urge for caressing from their pet Mimi, a grey spotted domestic cat, but instead of kindly showing Mimi the front door leading down to the …

March 6, 2013 – Review

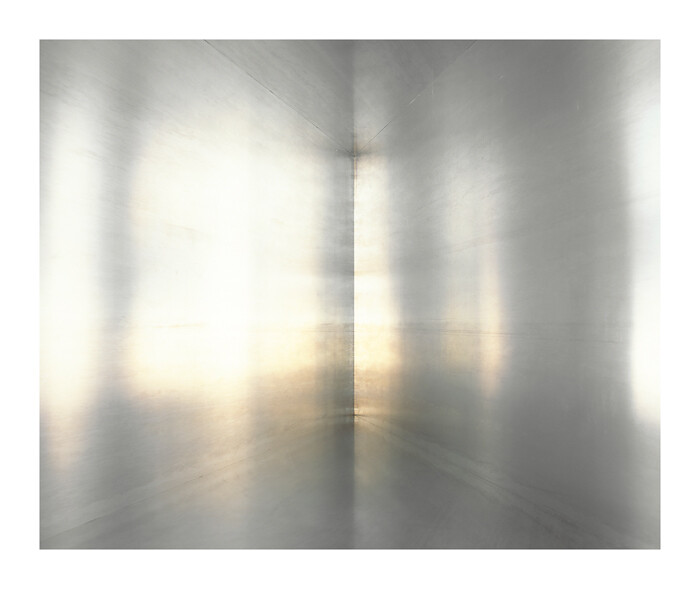

Luisa Lambri’s “New Works”

Barbara Casavecchia

Whenever I see a photo by Luisa Lambri, I think of a painting done by Gwen John (whose work remained in the shadows of her more famous brother Augustus until recently). It’s called A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris (1907–9) and it depicts a luminous corner of her attic: a wicker chair, a vase of flowers, the painter’s blue smock, a curtained window, and a triangular patch of pale sun. Although Lambri has always been attracted to corners and radiant apertures (windows, skylights, blinds) in private, domestic interiors, that’s not what sets my free associations into play. A Corner is obviously a self-portrait, even if John has subtracted her image from the frame. She painted it for seeing herself seeing, not for seeing herself being seen by others. In 2010, Lambri titled her exhibition at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles “Being There.” “I am photographing myself being there,” she explained of the photographs from which she was so obviously absent.

It’s the “the silent presence of another person”—as Michael Fried once described it—that confronts us in Lambri’s new series of prints at Studio Guenzani (where she held her first solo, back in 2000). They bring her gaze …

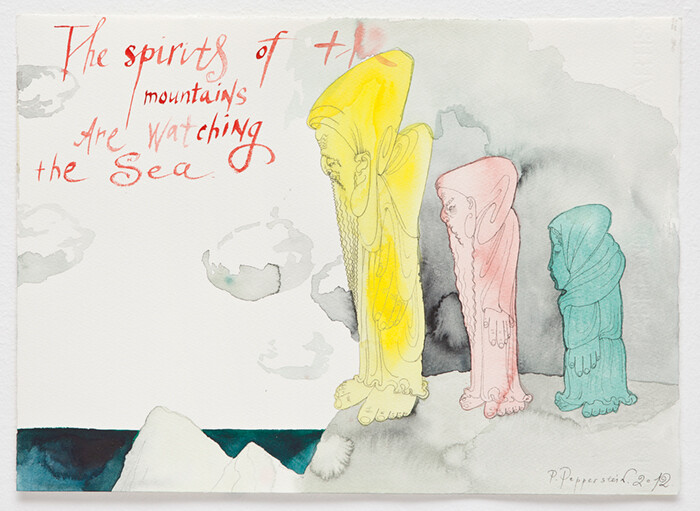

January 23, 2013 – Review

Pavel Pepperstein

Filipa Ramos

What happens when semiotic experimentation, psychedelia, and storytelling meet? This seemed to be the question that underpinned the very peculiar practice of a collective called Inspection Medical Hermeneutics, founded in Moscow in 1987 by three young artists—Sergei Anufriev (*1964), Yuri Leiderman (*1963), and Pavel Pepperstein (*1966). Of the three, Pepperstein is the one who remained closest to the ideals of the group, which he further developed on two main fronts: as a fiction writer and as a visual artist. In his vast body of work, the artist has explored the possibilities of combining linguistics, outlandish experiments, popular narratives, and science fiction in a way that seems to be immune to the ideals and expressive forms of post-perestroika. In fact, Pepperstein often combines traditional formats, such as storytelling and figurative drawing, and in doing so he assumes a radical position: that of changing by not changing at all.

Such is the case of Pepperstein’s exhibition of twenty watercolors from 2012, some of which bring back figures that have previously emerged in the artist’s drawings, characterized by a unique combination of political, cultural, and folk references. Also in the show are drawings that evoke similar atmospheres; familiar characters are represented in different situations …

January 7, 2013 – Review

“Gespräche über persönliche Themen: Miroslaw Balka and Roni Horn”

Barbara Casavecchia

There are portraits of two women in this exhibition by Miroslaw Balka and Roni Horn. Who knew that a portrait of a lady could reveal so much, that a portrait of a lady could become a portrait of the artist? It’s tempting to read these images as condensed biographies reflecting on individual art histories. Set up in the same room, they collide in an uncomfortable tête-à-tête. How appropriate, for a show titled “Gespräche über persönliche Themen” (Conversations about private themes), jointly conceived by the artists and installed like a neat conversation piece. The pairing marks the last episode of an annual program based on “duets” (Daria Martin and Anna Halprin; Michael Fliri and Asta Gröting), introduced by Raffaella Cortese to celebrate the opening of a twin space of her gallery on the same street.

First we meet Márgret Haraldsdóttir, who emerges from the hot pools of Iceland and whose face is as subtly changing as the clouds in an overcast sky in Untitled (Weather) (2011). Horn—who identifies with the nature of Iceland, a country she has been visiting regularly since her early twenties and made the chore of her personal “encyclopedia,” To Place (1990–ongoing)—asked Márgret to pose again for this series, …

July 19, 2012 – Review

Judith Hopf’s “A Sudden Walk”

Barbara Casavecchia

Blame it on Pippi Longstocking and a 70s-style, girl-power upbringing, but as a kid I too dreamt of living alone with a clever white horse called Old Man whom I could lift up with a finger. I refused to take too seriously the circus of adults who pretended to have a say about me. The idea of being boxed in by rules was insufferable. All those riotous feelings came back with a bang while visiting Judith Hopf’s solo show at kaufmann repetto, her first in Italy. Hopf’s evocation of horses and tigers—however tame or ironic—prompted an instinctive longing for freedom, a longing from all the prescriptive grammars of seeing and reacting to Art. An allergy to orders is, I guess, one of the reasons why the world of (caged, trained) animals is often such a sensitive subject for women artists—I could draw a long list here, from the great 19th century animalière painter Rosa Bonheur to Simone Forti’s choreographies inspired by her observations at the zoo, and Rosemarie Trockel, with her raucous motto, “Every animal is a female artist,” as a provocative response to Beuys’s “Jeder Mensch [ist] ein Künstler.”

What I found most enticing, however, is that Hopf stages her …

February 25, 2012 – Review

Ilya & Emilia Kabakov

Filipa Ramos

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s artistic proposals are not only inspiring but also very appropriate for our present times. It is hard to define the reason without sounding vague, because it is a sort of atmosphere, a suspension from the everyday world through the introduction of a parallel sphere that, if slightly different and not totally known, is capable of proposing sharp comments about the Real. Some of their works propose metaphors and parodies through a powerful allusive apparatus. They have a knack for generating “spaces within spaces,” a knack for creating empathy with the present. By stepping into a parallel realm, indeed, evasive of reality, the viewer is equipped and ready for a change in attitude, made possible through the Kabakovs’ continuous reflections about the relations between the individuals and the collectivity established by projections and desires; it is exactly this tension between evasion and acuteness that plays a fundamental role in our current relation to the everyday.

If we consider our present times of social, economic, and political uncertainty, and the major actions that have been shaking the world around us, from the upheavals at Tahrir to the waves of indignados ebbing and flowing into the squares and streets of …

December 1, 2011 – Review

Becky Beasley’s "The Outside"

Filipa Ramos

THE INTERIOR

“In truth we are men because we slide towards the useless material; otherwise we would be reduced to the biologically perfect condition of the better-organized colony of insects, where nothing happens that is not useful to material life,” wrote Carlo Mollino (1905–1973) in “Utopia e Ambientazione” (Utopia and Setting), an article published in two consecutive issues of Domus in 1949. It was not the first time that the architect employed quasi-anthropological observations in praise of inutility. During a public debate (1), Mollino continued that the only way to transcend technique was to slide towards uselessness. He wanted to open a way for the creation of non-necessary elements that, according to his own words, animate buildings, objects, and creations alike. His statement can be interpreted as a subtle critique of rationalism and an early anticipation of postmodernism. It may also justify the interest in Mollino, who has been recently re-presented as a figure whose transdisciplinary vocation largely exceeded the field of architecture, and whose propensity towards aesthetics caused such widespread fascination.

Becky Beasley’s exhibition “The Outside,” part two of the trilogy “Late Works,” is a visual digest of her survey on Carlo Mollino, and it provides yet another contribution to reinterpreting …

May 3, 2011 – Review

Neïl Beloufa’s “Changes of administrations” at Galleria ZERO, Milan

Filipa Ramos

Coming from a conceptual background with little connection to anything that moves, I have long been trying to understand what is at the core of the definition of the cinematic. The shattered space full of tiny wood objects, naïve drawings, photographs, photocopies, and roost-like structures for watching and listening to video projections, which constitutes Neïl Beloufa’s exhibition, opened the possibility of giving meaning to just such a word.

The gallery space is fragmented into irregular areas, many of them defined by minimal thresholds, such as delicate wooden structures or thin MDF half-walls. (One day someone will reflect upon the artistic use of the fiberboard on the early millennium and its symbolic value). Large, flat, green-painted surfaces prevail, and the inclusion of such impenetrable elements is a recurrent motive in many of Beloufa’s installations. In the guise of the blue-screen (which, in this case, is green) against which action is shot in the movies so that it can be superimposed by other sets, these green layers constitute a background that is not meant to exist—it is, in fact, an element that prepares our acceptance of filmic illusion or, rather, reinforces our acceptance of illusion, even in unlikely and technically imperfect cases. This …

February 28, 2011 – Review

"Are You Glad to Be in America?" at Massimo De Carlo, Milan

Filipa Ramos

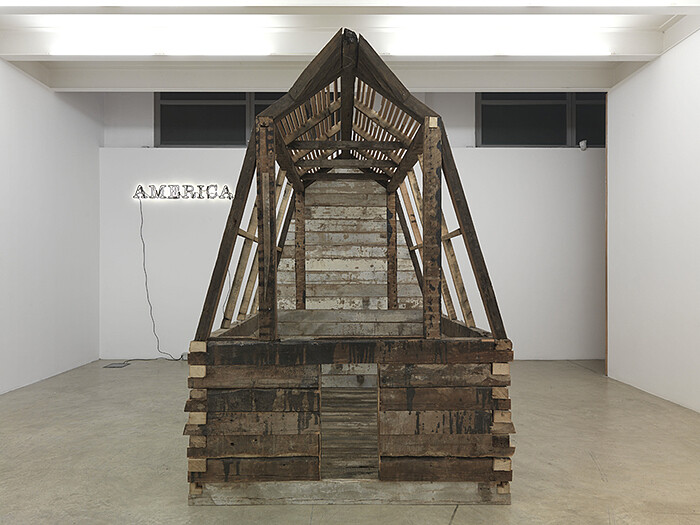

Macho, violent, and angry: such is the America portrayed in Galleria Massimo De Carlo’s inquiring exhibition.

The show opens with the remnants of a ghost town, a derelict shed, and all that is missing is the tumbleweed. But here what’s being referenced is not the Wild West, but rather the myth of it created by Hollywood. Next to this Barn Again (2010) by Marianne Vitale, and complimenting the Western stage-set appeal, is a neon sign that reads “AMERICA”—more like a heralding gateway than caption to the room. This work by Glenn Ligon, The Period (2005), presents a contradiction: simultaneously it plays with the cliché of identity while assuming the legacy of modern American light works—from Flavin’s minimal glowing tubes, across the conceptual valley of ready-mades, only to arrive at Jason Rhoades’s colourful slang.

Around this arid, self-reflexive image of America, printed lyrics from almost forty decades of Afro-American musicians (from the poetic spoken word of Gil Scott-Heron to the arrogant rap of Nas) are crudely stapled to the wall like renegade manifestos of popular culture. In a way, this “mute soundtrack” provides a particular tone to the show dedicated to the imagery of North America and also opens up access to one …

July 26, 2010 – Review

Mario Garcia Torres’ "I Will Be with You Shortly" at Peep-Hole, Milan

Filipa Ramos

Mario Garcia Torres is well acquainted with the past of Peep-Hole, one the newest non-profit spaces run by three curators in Milan. In fact, he not only alluded to it, but he also enhanced its weight. In a letter given to the visitor, the artist stated his wish to “create a certain atmosphere (…) an overall parenthesis, a space between time.” When entering the exhibition one has the impression of stepping inside a black-and-white film, for the presented works fit well within a palette of greys that is enhanced not only by the general darkness of the space, but also by a suave, constant melody that gives a peculiar tone to the whole place.

“I Will Be With You Shortly” is the first solo show of Garcia Torres in Milan and – as suggested by its title – it is an exhibition that deals with deferral, anticipation, expectation, and waiting. Despite its lascivious name, Peep-Hole is located in a historical place: in the early 1990s, it hosted Massimo De Carlo’s first gallery which then became an artist’s studio until its most recent incarnation.

The main room is very dim, only broken by two light sources. On the left, a ceiling lamp beams …

June 19, 2010 – Review

Paul McCarthy’s "Pig Island" at Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, Milan

Filipa Ramos

Solitude, abandon, restlessness, vulnerability: feelings a visitor might not expect to experience at the Palazzo Citterio. The refined 18th century rococo façade is at home in the elegant Brera district of Milan, but despite its chic external architecture, this sober face hides the perfect setting for Paul McCarthy’s delirious “Pig Island.” This exhibition displays iconic works from the Los Angeles artist together with new pieces, resulting in a complex installation that is a single, coherent articulation of McCarthy’s rhetoric and multifarious forms.

The Palazzo’s first room contains a crumbled figure of George Bush sodomizing a pig’s carcass amidst an endless array of (clearly allegorical) detritus—this rosy mass resembles the leftovers of a huge wedding cake. Static (Pink) (2004-2009), is a monument to an expired struggle: while that specific war is over, as well as the ideology it resisted, what remains is the decadent mourning of art’s impotency. Next to Static (Pink), in a dim, soiled, humid corner, an old man with no pants sleeps on a precariously small cot. It is clearly a portrait of the artist, so realistic that you have to get very near to it to confirm whether it is breathing. The closer you get, the more miserable …

Load more