Acker-Web

There are many ways in which Kathy Acker remains our contemporary. Some most excellent writing has made for us Ackers who speak a literary language for our time. What makes a writer live on after their own life and fame is nothing particular. It is that their writing can be made into all sorts of different writing afterwards. It is that their writing contains still pertinent possibilities.

The Acker I want to write into existence is not a literary one. And nor do I want to write as if there is only one Acker. There was always an Acker-field or Acker-text or Acker-web in which lots of Kathys pulsed and ebbed in and out of identity, alongside plenty of Janeys and Lulus. And not all of her identities, in life or art, were female.

There was, I think, an Acker or series of Ackers in the Acker-web who were not writers of fiction but of theory. A low theory of feminist revolution, but where “feminist” and “revolution” come to mean other things. From the vantage points of New York, San Francisco, and London, these Ackers saw the political economy of the old overdeveloped world die, and something else bubble up through the cracks. Leaning heavily on her own sentences, I want to rip off and copy out for you what the Acker-web has for us on the current topics of post-capitalism, agency in the world, revolution, and aesthetics.

Post-Capitalism

Post-capitalism has two senses in the Acker-web. One is the revolutionary possibility of life without exploitation, but the other is that exploitation itself might have changed form. This might then still be a world with a ruling class extracting a surplus from dominated classes, including labor as traditionally understood, but which might also have added some other means of domination to its arsenal.

“You never recognize an end when it’s happening.”1 But from the vantage point of New York, London, and San Francisco, Ackers witnessed this strange post-capitalism emerge as it extended the commodity form into aesthetics and information, but in the process modified the commodity form itself. Ackers witnessed a quiet but violent transition: “my reality, between post-industrial and computerization.”2

Sometimes it is in its own self-identity eternal, but with new qualities. “The multinationals and along with their computers have changed and are changing reality. Viewed as organisms, they’ve attained immortality via biochips.”3 Commodification as control seizes hold not just of labor but of everything. “Capitalism needs new territory or fresh blood.”4 It has colonized all of the domains of the sacred and subordinated them to itself.

Some Ackers detect a strange mutation in the mode of production, features that are no less about exploitation but might work in strange ways, display odd “post-capitalist money-powers.”5 The art world, for instance, becomes a prototype for some kind of political economy of information. “I call these years THE BOHEMIA OF FINANCE (that’s what I called the art world).”6

The quantitative information that is money and the qualitative information that is aesthetics meet in some peculiar way. “Her gown is Chanel, not Claude Montana nor Jean-Paul Gaulthier. Money, not being Marxist, is worshipping humanity, as it should.”7 That’s a particularly curious sentence. A human who is caught up in fetishism sees only the dance of money and things, but a more critical human might see beyond the thing to the labor that made it. Uncritical money, like the uncritical human, is fetishistic, but what it makes a fetish is not the commodity, but the human. All it can see now is humans exchanging things that are brands, that are qualitative information. It can’t see labor and production, the material world, either.

A provisional theory of this wrinkle in the old mode of exploitation is to conceive of it as adding to the separation between use and exchange value a separation between the signified and signifier aspects of the sign. Exchange value converts the qualities of the active body into something extractable and measurable. It turns substance into commodity. Post-capitalism adds the extraction of the value of signifieds: emotions, sensations, desires, through the capture and ownership of signifiers. They are our feelings, lusts, needs; but owned and controlled now through their brands, copyrights, patents.

This post-capitalism might commodify information rather than things. “Products are out of date. No one can afford to buy anyway.”8 And: “Since the only reality of phenomena is symbolic, the world’s most controllable by those who can best manipulate these symbolic relations. Semiotics is a useful model to the post-capitalists.”9

Theory: The separations between signifiers and signifieds are widening … the powers of post-capitalism are determining the increasing of these separations. Post-capitalists’ general strategy right now is to render language (all that which signifies) abstract therefore easily manipulable. For example: money. Another example is commodity value … In the case of language and of economy the signified and the actual objects have no value don’t exist or else have only whatever values those who control the signifiers assign them. Language is making me sick. Unless I destroy the relations between language and their signifieds that is their control.10

Rather than anomaly, outlaw, outlier to capitalism, the artist becomes the prototype of a kind of human within what capitalism has become. Money as information about quantity wants aesthetics as information about quality. It wants artists, but it makes artists over entirely as what they always were at least in part: hustlers—whores. “Imagination was both a dead business and the only business left to the dead.”11

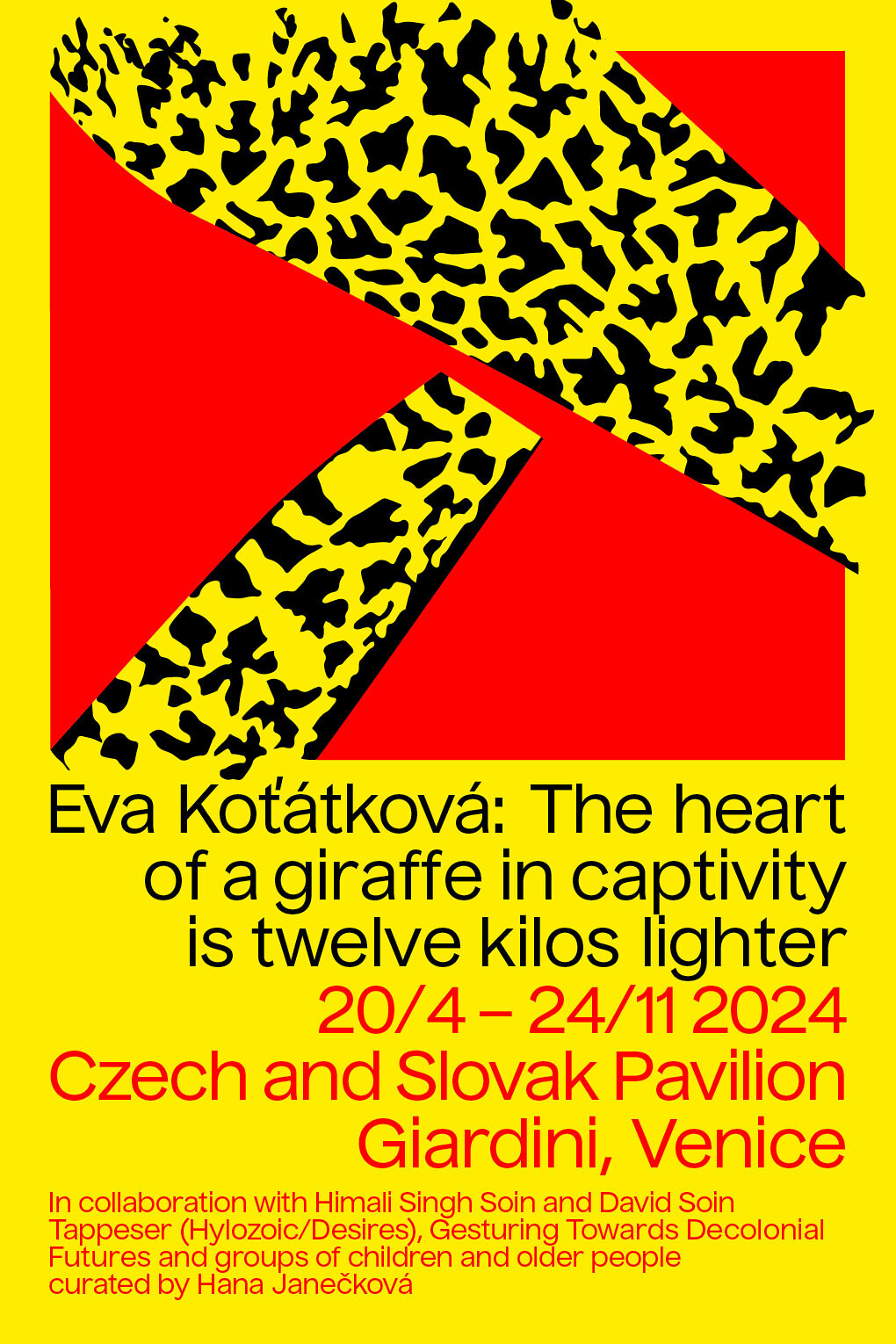

Laura Parnes, Blood and Guts in High School, 2004-2009. Pictured left to right are actors Stephanie Vella and Jim Fletcher. Courtesy of the artist.

Agency

If there’s a collective agency in the Acker-field, it is those who don’t own capital but who also don’t exactly do wage labor, either. Some are successful and honored, and get to call themselves artists. Many are not. They come in a few types that are hard to put names to, as they are never at home in any name. They are the tip of the melting iceberg of the homelessness of the world.

“Romanticism is the world. Why? Because there’s got to be something. There has to be something for we who are and know we’re homeless.”12 While skeptical of the romantic in several other senses, most Ackers hold on to this: the agency of the displaced, the marginal, the recalcitrant, and through them, the possibility of the world. Possibility alone is not enough, however. “Every possibility doesn’t become actual fact. So knowing is separate from acting in the common world.”13

These displaced ones all too often find no possibilities in the world. This sensibility in part looks back to a persistent sense of aesthetic or poetic rebellion and its foils. “I saw my friends in that brothel destroyed by madness starving hysterical naked dragging themselves through the whitey’s streets at dawn looking for an angry fix I saw myself fucked-up nothing purposeless collaborating over and over again with those I hated old collaborating with my own death—all of us collaborating with Death.”14

The margin of possibility may have become very slight. Not only the effort of labor but the effort of feelings, sensations, pleasures, pains, concepts—information—is entirely within the post-capitalist commodity form and modifies that form. “The realm of the outlaw has become redefined: today the wild places which excite the most profound thinkers are conceptual. Flesh unto flesh.”15 And: “Now there’s no possibility of revolting successfully on a technological of social level. The successful revolt is us; mind and body.”16 To refuse even part of corporeal existence to the commodity form, “you have to become a criminal or a pervert.”17 At least in the eyes of the ruling class.

For some of us it’s not a choice. “I didn’t choose to be the freak I was born to be.”18 Some of those freaks who were called queers decided to wear that name with pride. So if we can be queers then why not also be whores? How about some whore pride? To celebrate queerness is often a way to avoid talking about labor or the sale of the sensual, fascinating, or erotic body. To celebrate whores is to connect the deviant body back to its place in the mode of production.

In the Acker-web there might be a lot of ways to be a whore. It might and might not mean sex worker. Whoring might include a lot of other transactions, including those of artists. But the key quality is the struggle to remain a free agent, not becoming anyone’s possession: “A whore goes from man to man; she’s no man’s girl.”19 The rebellion of the whores: “We got rid of our johns, now our dreams don’t mean anything.”20 To be neither owned nor rented, by anyone. To extract the body from the commodification of its surfaces and signs.

Whores might be a more promising kind of being in the world of post-capitalism than artists. Artists alone are too compromised a form of agency: “revolutionaries hiding from the maws of the police which are the maws of the rich by pretending they’re interested only in pleasure.”21 The artist might once have been privileged by being marginal to capitalism whereas in post-capitalism they become more integral to a commodity form that absorbs information out of the not-quite-laboring activities of bodies.

Not kin but kith to the art-boys are the punk-boys. “To be kissed by a punk boy was to be drawn to insanity or toward death. The last of the race of white men.”22 They only count as punks if they are at least trying to escape from whiteness and masculinity, which is to say, escape from identity. They benefit from openness to tutelage. “The whores explained to the saints that they were voyaging to the end of the night.”23

The pirate is an ambivalent figure, an amoral agent, homeless and lawless. “The pirates knew, if not all of them consciously, that the civilizations and cultures that they were invading economically depended on the enslavement of other civilizations and cultures. Pirates took prisoners, didn’t make slaves.”24

Pirate and whore form mythic couplings and doublings. “The pirates loved women who were sexual and dangerous. We live by the images of those we decide are heroes and gods. As the empire, whatever empire, had decayed, the manner of life irrevocably became exile. The prostitutes drove mad the pirates, caught, like insects in webs, in their own thwarted ambitions and longings for somewhere else … The pirates worshipped the whores in abandoned submission.”25

Pirates escape the laws even of gender. “Pirates aren’t always either male or female.”26 “Pirate sex began on the date when the liquids began to gush forward. As if when equals because. At the same time, my pirate penis shot out of my body. As it thrust out of my body, it moved into my body. I don’t remember where.”27

Pirate sexuality is outside of gender, outside the commodity form: “On dreams and actions in pirates: Their rotten souls burn in their bowels. They only go for pleasure. For them alone, you see, naked bodies dance. Unseizable, soft, ethereal, shadowy: the gush of cunts in action.”28

Not being enclosed in identities, pirate-whores have neither subjectivity, nor are they objects made over by commodification. “For the first time, I was seeing the pirate girls in their true colors. Black and red. They wore their insides on their outsides, blood smeared all over the surfaces. When opened, the heart’s blood turns black.”29

Punks, whores, pirates: One can become another, or is more than one at once. And all can be sailors. “In order to see, I have to touch or be what I see. For this reason, seers are sailors. When seers become artists, they become pirates. This’s about identity.”30 Identities don’t have to disappear, they just become transitive, temporary. Sail through times and spaces and they happen.

Sailors are not bound within any territory or home. They come into existence in the difference between times and spaces. “Sailors set out on perilous journeys just so they can see in actuality cities they have only imagined.”31 “A sailor is a man who keeps on approaching the limits of what is desirable.”32 “Since ANY PLACE BUT HERE is the motto of all sailors, I decided I was a sailor.”33 And: “A writer’s one type of sailor, a person without human relationships.”34

Perhaps the sea was central rather than peripheral to the actual history of capitalism. From whaling to slaving, the sailor was caught up in commodification at its most naked. Sailors are free agents to most Ackers, although in actuality many were pressed labor. Perhaps also there is an imaginary sea that was an open plain along which to flee. “I always wanted to be a sailor … Sailors leave anarchy in their drunken wake … A sailor is a human who has traded poverty for the riches of imaginative reality … A sailor has a lover in every port and doesn’t know how to love. Heart upon heart sits tattooed on every sailor’s ass. Though the sailor longs for home, her or his real love is change … No roses grow on sailor’s graves.”35

This imaginary sea becomes a plain along which to flee post-capitalism. Sexuality, the city, and writing can be the oceans within which sailors wander. Or maybe even the body as it is supposed to be organized is a thing to flee. “Let your cunt come outside your body and crawl, like a snail, along the flesh. Slither down your legs until there are trails of blood over the skin. Blood has this unmistakable smell. Then the cunt will travel, a sailor, to foreign lands. Will rub itself like a dog, smell, and be fucked.”36

Artists, punks, whores, pirates, sailors. And then there’s lawless, fatherless girls, whose possible being-together some Ackers glimpsed backstage at a sex show. And yet the girl too is not an identity but an event, something produced by chance and fluid time. Lulu: “You can’t change me cause there’s nothing to change. I’ve never been.”37

There might be many kinds, which is a problem, as sometimes they want nothing to do with each other. “Girls have to accept girls who aren’t like them.”38 A girl is a node of attraction but also of vulnerability, whose actions are constrained by others’ desires and violence—by men’s desires and violence. Their vulnerability is their agency. Their possibility is in refusing the legitimacy of any agency that is not at least in part girl.

To be a girl in the world is a fearful but also a fearsome thing to be: “Doctor, I’m not paranoid. I’m a girl.39 But in the world, their only power is in their amorality and ability to exploit their own desirability: “In reality, the girl was desperate to fuck and scared to fuck because fucking was how she earned money and got power.”40

The girl said:

You understand that it’s only with the highest form of feeling (whatever that is) and not because we hate you that we’re going to take our ease in your homes and mansions, your innermost sanctuaries, we’re going to sleep in your beds (you want us to anyway) on your unbloodstained mattresses on the sheets on which you fuck your wives. We want to feed on your flesh. We want—we’re going to reproduce only girls by ourselves in the midst of your leftover cockhair, in your armpits, in whatever beards you have. We’re going to sniff your emissions and must while we’re penetrating (with our fingers) your ears, nostrils, and eye sockets. To ensure that you’ll never again know sleep … In the future, we’ll never conceal anything about ourselves (unlike you) because our only purpose here is the marking of history, your history. As if we haven’t. Because you said that we hadn’t.41

Revolution

Artists, punks, whores, pirates, sailors, girls: makers of the sense and sign and heat of their own bodies. But who find the signs they emit captured and owned and used against them. And that’s at best. That’s when their bodies and minds are not violated and gas-lit and punished. So: “Why’re we asslicking the rich’s asses?”42 It’s time for “a revolution of whores, a revolution defined by all methods that exist as distant, as far as possible, from profit.”43 It’s time to declare: “I won’t accept that this world must be pain: A future only of torment is no future for anyone.” 44

Such a revolution can’t ignore how intimate commodification has become, how close it presses its exchange-value carving knives into the flesh. “Is liberation or revolution a revolution when it hasn’t removed from the faces and bodies the dead skin that makes them ugly? There’s still dead blood from your knife on one of my cunt lips.”45

Some Ackers dream of a libidinal revolution. “If we lived in a society without bosses, we’d be fucking all the time. We wouldn’t have to be images. Cunt special. We could fuck every artist in the world.”46 And: “Soon this world will be nothing but pleasure, the worlds in which we live and are nothing but desires for more and more intense joy.”47

Others are a little skeptical. Even a brief experience of sex work and of the so-called sexual revolution as it was practiced (mostly for the benefit of men) in the late twentieth century rather cools an Acker’s ardor for it. It can’t be as imagined by penetrators, as the availability of the world to their dicks. Those dicks can now be detachable, interchangeable, or optional. “In the future, I will be the sun, because that is what my legs are spread around.”48

Some Ackers have a more destructive character, but hold on to the potentials that the negation of this world hide in their shadows: “Revolutions or liberations aim—obscurely—at discovering (rediscovering) a laughing insolence goaded by past unhappiness, goaded by the systems and men responsible for unhappiness and shame. A laughing insolence which realizes that, freed from shame, human growth is easy. This is why this obvious destruction veils a hidden glory.”49

There are many Ackers who start to dream of revolution not from the events of pleasure but of pain. “I am a masochist. This is a real revolution.”50 “Masochism is now rebellion.”51 “Masochism is only political rebellion.”52 “Freedom was the individual embracement of nonsexual masochism.”53 Because: “Pain is only pain and eradicates all pretense.”54 Masochism is not just a kink or a pathology: “Each time I slice the blade through my wrist I’m finally able to act out war. You call it masochism because you’re trying to keep your power over me, but you’re not going to anymore.” 55

And yet there’s no attempt to make the sexuality of whores, pirates, and perverts something respectable, each with its own flag and T-shirt. The goal is not queer citizenship in the existing state through legitimizing its various identities. Rather: “Valiant beasts; because your sexuality does not partake of this human sexuality … I will now lead you in a fight to death or to life against the religious white men and against all of the alienation that their religious image-making or control brings to humans.”56

It will be a revolution of the penetrable, or perhaps of the reversible, of surfaces that can open but also swell to fill corresponding voids. A revolution against ownership by that which gives away ownership of itself: “They said it was a hole, but it was impossible for her to think of any part of herself as a hole. Only as squishy and vulnerable flesh, for flesh is thicker than skin. She was wet up there. When she thrust three of her fingers in there, she felt taken.”57

The penetrable are not nothing, not voids for the master’s voice or dick. They—we—are not the other, the lack, the supplement, the second sex-organ. We don’t need them even if we want them. To want to be fucked need not be to want all that comes with it. In the post-capitalist world, the hole without the dick is also labor without capital. A refusal of all that the dick signals, a refusal of being dicked by signals that are shorn of the writhing, pullulating, concentrating bodies that make them.

It’s the revolution of the girls who are willing; willing to give up themselves, but who no longer need to be taken. “The more I try to describe myself, the more I find a hole.”58 One does not have to say yes to power to become a void, even if that’s how it usually works: “He made her a hole. He blasted into her.”59 In any case, maybe the other side of the penetration of the hole by the dick is the encirclment of the dick by the hole.

Any body can void itself. “All of him wants only one thing: to be opened up.”60 “A hole of the body, which every man but not woman … has to make, is the abyss of the mouth … Today, all that’s interior is becoming exterior and this is what I call revolution, and those humans who are holes are the leaders of this revolution.”61 The mad quest of those with inverse lances: “To become a knight, one must be completely hole-y.”62

The holes need not be the obvious ones: cunts, asses, mouths. The ears and nose are holes. “For me, every area of my skin was an orifice; therefore, each part of the body could do and did everything to mine.”63 The body is infinitely penetrable. And what’s in there is not nothing. Nor is it the essence of the self, some private property of the soul. “‘I’ is not an interior affair.”64

The revolution of the penetrable is not just about bodies. The body of the city, also: “The pipes, fallopian tubes unfucked, unmaintained, wriggled, broke, burst open, upwards, rose up through all the materials above them.”65 And: “Water pipes burst through the streets’ concrete. Through these holes. Through holes in the flesh, the faces of the dead stare at the living … Through human guilt, we can see the living.”66 And: “The landscape is full of holes, something to do with what should be the heart of a country.”67

There’s a risk in any will to revolution. There’s a risk to opening up the body beyond its restricted repertoire. “If we teach these champagne emotions are worth noticing, we’re destroying the social bonds people need to live.”68 It’s the chance of another life against the certainty of slow death. A death not just of bodies, but also cities, even of nature itself.

“Either this is a time for total despair or it’s a time of madness. It’s ridiculous to think that mad people will succeed where intellectuals, unions, Wobblies, etc, didn’t. I think they will.”69 All the old gods die in the Acker-web. After the death of god comes the death of man, of imagination, of art, of love, of desire, of history. The good order won’t result from making anything else sacred in the absence of god. Instead, only an experimental living with disorder.

A revolution of wild gone girls. In the footsteps of the “Nameless, the pirates of yesteryear.”70 It is a nihilist vision of revolution. The stripping bare of bodies and values reveals a world without aura, justice, or order. It becomes instead a world of violence and chance. The violence has to be felt, has to be known, so it can be deflected. That’s the particular role of masochism, as a way of refusing to pass on violence to some other body, the way a certain kind of radical feminism ended up deflecting the violence it won’t acknowledge onto transwomen.

Nihilism acknowledges a world both of violence but also of chance. The god of history is dead. Noise and disorder won’t be resolved at the end of history. But then neither is it entirely a world as an iron cage, enclosed in ever more perfect surveillance and rationalization. If there’s chance, there’s still no hope, but there’s a chance.

Aesthetics

“We Have Proven That Communication Is Impossible.”71 Communication only creates fictions: the fiction of the object as a separate thing, the fiction of the self that can know and own the object, the fiction of a reliable means of relating object and subject, the fiction of the fluctuating fortunes of objects and subjects being resolved somewhere or some time, the fiction of a measurable and calculable time within which objects or subjects are self-same.

The Acker-field is a sequence of books about—no not about. They are not about anything. They don’t mean, they do. What do they do? Get rid of the self. Among other things. For writer but also reader. If you let them in. You have to want it to fuck you. It happens when there’s a hole. “The only way is to annihilate all that’s been written. That can be done only through writing. Such destruction leaves all that is essential intact. Resembling the processes of time, such destruction allows only the traces of death to persist. I’m a dead person.”72 Such a reduction expels meaning from the text and subjectivity from the body at once.

The risk, the challenge, is to go even further into the devaluation of all values. “My language is my irrationality. Desire burns up all the old dead language morality. I’m not interested in truth.”73 The feeling of being in a post-truth world really accelerated in the twenty-first century. The transgressors of official pieties, of which Acker might be a celebrated example, are made scapegoats for a phenomenon that they had the audacity to expose. The stripping of information from bodies, a new kind of commodification, casts all anchored truths to the winds, not those writers or artists who noticed.

An Acker: “And the men—well, there seems to be some sort of crisis; the men seem to be absolutely floundering about” (AW179). The panic attack of feeling exposed to information without meaning, stripped from its bodies and situations, caused a stampede among those who cling tight to their tattered rags of identity: whiteness, masculinity, petit-bourgeois exclusion, all went looking for ways to circle the fictional wagons, close the gates, and amp up streams of actual and symbolic violence to keep identity afloat on the rising tides.

“I’d like to say that everything I do, every way I’ve seemed to feel, however I’ve seemed to grasp at you, are war tactics.” 74 Tactics can change. The war has a new contour. This tactic might seem a little out of date: “For any revolution to succeed nowadays, the media liberals and those in power have to experience the revolt as childish irresponsible alienated and defeatist; it must remain marginal and, as for meaning, ambiguous.”75 Media liberals and those in power are no longer quite the same thing. However, media liberals and those in power still both profit by amping up attack-information directed at each other.

Regardless of whether one is preferable to the other, neither is really the friend of that revolting class of whores, pirates, punks, sailors, and autonomous girls that post-capitalism pokes with its social media prompts to gin up commodified desire. A revolting class quickly put in its place if it confronts the ruling class head on. A ruling class for whom America is really a one-party state which, with typical American largesse, has two parties. If that’s the contours of it, then to appear childish and unthreatening seems like a survival tactic worth recalling from past information wars. Dwell in the void of the noise.

How to be a writer who actually writes for their own times and not as if the nineteenth century machinery of the novel still had a world with which to engage? Ackers are nearly all prose writers. Their sentences are regular, logical sentences, artless at first glance but often constructed with the elegance of the minimal. Rather than break the sentence, they break the expectation of what the sentence is supposed to do: function as a container for hidden reservoirs of meaning unique to the author’s mind.

This Acker: “Language is more important than meaning. Don’t make anything out of broken-up syntax cause you’re looking to make meaning where nonsense will. Of course nonsense isn’t only nonsense. I’ll say again that writing isn’t just writing, it’s a meeting of writing and living the way existence is the meeting of mental and material or language of idea and sign.”76 The chosen tactic is prose fiction, not poetry.

“I tell you truly: right now fiction’s the method of revolution.”77 Rather than shore up some other identity against hegemonic whiteness, masculinity, and petit-bourgeois privilege, strip the last charms from identity itself. Disenchantment: “As soon as we all stop being enchanted … human love’ll again be possible.”78 And then: “It’s the end of the world. There are no more eyes.”79

What I have always hated about the bourgeois story is that it closes down. I don’t use the bourgeois story-line because the real content of that novel is the property structure of reality. It’s about ownership. That isn’t my world-reality. My world isn’t about ownership. In my world people don’t even remember their names, they aren’t sure of their sexuality, they aren’t sure if they can define their genders. That’s the way you feel in the mythical stories. You don’t know quite why they act the way they act, and they don’t care … The reader doesn’t own the character.80

The Acker-text is not a career of novels. “Everything in the novel exists for the sake of meaning. Like hippy acid rock. All this meaning is evil. I want to go back to those first English novels … novels based on jokes or just that are.”81 The plot of the novel is the marriage of sexuality with property. Sexuality is enabled by, or confined by, property. The books are marketed as novels, but it’s no fun to read them as such. They are caught in an ambivalent space, as all artwork is, between work and property, signified and signifier. These days they get some terrible Amazon reviews from readers who want them to mean something.

The Acker-text is more a texture of fictions: “I write in the dizziness that seizes that which is fed up with language and attempts to escape through it: the abyss named fiction. For I can only be concerned with the imaginary when I discuss reality or women.”82 Rather than a women’s writing that tries to inhabit the old forms, it’s a refusal of it, and a refusal then also of those forms that would confine what woman can mean by insisting that it be a kind of subject that means things.

The Acker-fictions don’t ask you to figure out what lies beyond the signifier much past the level of what the words denote. Sure, you can read into them, into their connotations. Maybe it’s impossible not to. You can guess at what might be the referents to which the signs refer in the world. But you don’t have to read into it too much. You can look at the page and see writing, see a form of language, see what it does. What it did to you.

This Acker:

Once more we need to see what writing is. We need to step away from all the business. We need to step to the personal … We need to remember friends, that we write deeply out of friendship, that we write to our friends. We need to regain some of the energy, as writers and as readers, that people have on the internet when for the first time they email, when they discover that they can write anything, even to a stranger, even the most personal of matters. When they discover that strangers can communicate to each other.83

This Acker is a nineties Acker, writing before post-capitalism moved on to the extraction of value out of asymmetries of information, using the internet as infrastructure. Maybe the goal might remain, however: a writing-and-reading between bodies rather than subjects, a selving rather than a (non)communication between selves. Here there’s a stability that runs from that Acker who made serial works sent as gifts by mail in the seventies and that other, later Acker experimenting with collaborative writing on the internet in the nineties, back when it was, in several senses, free.

The writer, as a kind of artist, is caught up in the inconsistencies of communication, at least as post-capitalism was shaping it. Language can circulate almost for free, and certainly in ways that can’t readily be commodified. Or at least they could. A revolutionary writer is on the side of the free intercourse of signs and bodies. And yet a writer is also a whore, renting or selling a capacity of the body, allowing what’s signified to be separated from what’s intimately felt. “Property is robbery … If I’m being totally honest I would say that what I’m doing is breach of copyright—it’s not because I change words—but so what? We earn our money out of the stupid law but we hate it because we know that’s a jive. What else can we do? That’s one of the basic contradictions of living in capitalism.”84

To be revolutionary it might not be enough that writing is as outside the commodity form as is possible. This might need to enter the body of the text in a certain way as well, in the form of a writing that refuses the stripping of signs from bodies, signifiers from signifieds, so that they might become the property of the reader and a receptacle for the reader to insert their own meanings.

There might be a language on the other side of that language, glimpsed in gasp or sigh. But actualized by pressing even further into the fiction of language.

Any statement beginning “I know that …” characterizes a certain game. Once I understand the game, I understand what’s being said. The statement “I know that …” doesn’t have to do with knowing. Compare “I know I’m scared” to “Help!” What’s this language that knows? “Help!” Language describes reality. Do I mean to describe when I cry out? A cry is language turning in on its own identity, its signifier-signified relation. “To of for by” isn’t a cry or language-destroying-itself. The language has to be recognizably destroying itself.85

Fiction is a texture made up of what expresses itself out of this body in particular but articulated through any self whatever.

Kathy Acker, In Memorium to Identity (Grove Press, 1990), 111.

Kathy Acker, Literal Madness: Three Novels (Grove Press, 1987), 313.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless (Grove Press, 1989), 83.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 33.

Kathy Acker, Don Quixote, Which was a Dream (Grove Press, 1986), 71.

Kathy Acker, Portrait of an Eye: Three Novels (Grove Press, 1998), 148.

Acker, Don Quixote, 84.

Kathy Acker, Hannibal Lecter, my Father (Semiotext(e)), 76.

Acker, Literal Madness, 293.

Acker, Literal Madness, 300–01.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 35.

Acker, Hannibal Lecter, 58.

Acker, Don Quixote, 54.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 145.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 140.

Acker, Literal Madness, 300.

Acker, Hannibal Lecter, 34.

Acker, Literal Madness, 278.

Kathy Acker, Great Expectations (Grove Press, 1989), 116.

Kathy Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates (Grove Press, 1996), 54.

Acker, Portrait of an Eye, 111.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 41.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 41.

Kathy Acker, My Mother: Demonology (Grove Press, 1994), 109.

Acker, My Mother, 112.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 112.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 114.

Acker, My Mother, 109.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 265.

Acker, My Mother, 101.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 118.

Acker, My Mother, 13.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 156.

Acker, Hannibal Lecter, 51.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 113.

Acker, My Mother, 59.

Acker, Don Quixote, 78.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 264.

Acker, In Memorium to Identity, 138.

Acker, In Memorium to Identity, 140.

Acker, My Mother, 51.

Acker, Don Quixote, 123.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 30.

Acker, Don Quixote, 163.

Acker, In Memorium to Identity, 46.

Acker, Portrait of an Eye, 201.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 32.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 116.

Acker, In Memorium to Identity, 45.

Acker, Great Expectations, 52.

Acker, Don Quixote, 158.

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless, 58.

Acker, Don Quixote, 118.

Acker, Don Quixote, 140.

Acker, Literal Madness, 300.

Acker, Don Quixote, 178.

Acker, In Memorium to Identity, 140.

Acker, My Mother, 22.

Acker, Hannibal Lecter, 38.

Acker, In Memorium to Identity, 13.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 20.

Acker, Don Quixote, 13.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 22.

Acker, My Mother, 211.

Acker, My Mother, 91.

Acker, My Mother, 106.

Acker, In Memorium to Identity, 115.

Acker, Great Expectations, 122.

Kathy Acker, Blood and Guts in High School (Grove Press, 1989), 127.

Acker, My Mother, 95.

Acker, Great Expectations, 27.

Acker, My Mother, 123.

Acker, Literal Madness, 215.

Acker, Blood and Guts in High School, 127.

Acker, Literal Madness, 299.

Acker, Literal Madness, 246.

Acker, Literal Madness, 271.

Acker, Don Quixote, 102.

Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, 71.

Acker, Hannibal Lecter, 51.

Acker, Literal Madness, 317.

Acker, My Mother, 80.

Kathy Acker, Bodies of Work: Essays (Unviersity of Michigan, 1997), 103.

Acker, Hannibal Lecter, 12.

Acker, Literal Madness, 313.