Admission starts at $5

July 1–3, 2022

172 Classon Avenue

Brooklyn, NY 11205

USA

We hope you’ll join us on Friday, July 1 and Sunday, July 3 for Tulapop Saenjaroen: A (Digressive) Focus Program, taking place at e-flux Screening Room and Library. The program features two screenings and a reading, presenting recent films by Tulapop Saenjaroen in dialogue with text, audio, and moving-image works by Kelley Dong, Anahita Jamali Rad, RUTMEAT, Anocha Suwichakornpong, Evan Calder Williams, Jia Zhangke, and Zheng Yuan, programmed by Steff Hui Ci Ling.

“Tulapop Saenjaroen’s videos swerve around serious and whimsical subjects and moods. Just in the same way that work and leisure in this world are too close for comfort, Saenjaroen’s contemporary work subjectivities traverse a spectrum of relaxation, experimentation, and social relationships as they take on shades of self-medication, exploitation, networking, and multi-performing for the diffuse labor market. However, the videos do not depict workers working, but present work within a theater of his cinematic construction.

Departing from the failed factography of social realism and its historical political agendas, this program recognizes work without workers, workers between work but not exactly not working, and people who are working in order to work, in order to present methods beyond the sheer representation of working that instead describe how modern labor is (de)materialized, (de)regulated, and (dis)organized.

Organized in three parts, the program is loosely arranged around a pair of themes: work and non-work. While a focus program conventionally, well, focuses on a single artist, I wanted to put together a “digressive” focus program that is anchored in the ideas and questions compelled by Tulapop’s practice, and present them in dialogue with other artists’ works, ideas, and questions that have been deepened by my viewing and thinking about his videos. Through some of the associative pathways and surprising motifs that have surfaced while making the program, these works mutually offer ways to reflect on Tulapop’s works too. I hope that this program can pique our labor consciousness, and offer insight, through abstraction and storytelling in cinema, into our individual and collective experience of navigating our agency between work and non-work.”

—Steff Hui Ci Ling

In the absence of the artist, the program is presented alongside a new interview with Tulapop Saenjaroen in conversation with Leo Cocar.

Leo Cocar (LC): In your work, you use a variety of found footage, such as clips from the internet, to structure the narrative through montage. Despite sudden aesthetic shifts between styles of storytelling, these shifts fluidly propel the ideas embedded in the script. Rather than composing these elements beforehand, shooting and writing unfolds in a continuous process during production.

Tulapop Saenjaroen (TS): I didn’t intend to do nonfiction work because I’m also interested in making characters. Initially, I was very skeptical about documentary, as a style, and also the image, in general. I feel like I need to fictionalize it, and give it another layer.

LC: Your skepticism of the image and the camera leads to some really interesting self-reflexivity in your films. In A Room With A Coconut View (2018), there’s a passage where the narrator talks about the paradox of the camera, stating “…an image can ever only show what is in the frame but can never show only what is in the frame.” The camera is a mediating device, not only mediating what’s within the shot, but mediating the camera operator as a figure in the broader context of image production. This comes up in People on Sunday (2020) where all of a sudden the film cuts and then the cameraman is talking about his own role in the production of images, and how the labor of it all is exhausting.

TS: When I think about an image or a certain style, or aesthetics in general, I feel like I always question, Who made it and what is it for? Why is it framed in this particular way? What is left out? My skepticism towards looking at things is that I also question myself, like, Why do I feel the way I do? Why do I think the way I do? A very silly example is, like, if you haven’t seen a dog in your life and then you see a picture of a dog; you might think very differently about it if you already have prior knowledge about dogs as a category. That’s where the aesthetic and the political kind of crash, I think.

Skepticism is not taking what is in front of you for granted because there are layers of complexity surrounding the object of enquiry. That’s why I always want the camera to be quite distant from the subject, but also very self-conscious in a way that provokes a feeling in the audience that they are a complicit part of the film itself. I want to create a sense for the viewer that you are not entering the fictional space of the film, but rather living alongside it, in the space of cinema.

LC: You’re saying the films are gesturing towards the viewer’s complicity in the process of image production?

TS: Yeah. We’re entangled in that power structure. This is where the fictive element comes in, because when I write my voiceover, I tend to write them as a character. They’re just like a person. So they don’t say everything that they feel. They only say whatever they want the audience to know. Everything becomes unreliable.

LC: Do you have similar considerations when you’re editing?

TS: An overarching theme in editing has something to do with destabilization—it comes back to skepticism and re-reading the image and its interpretation. The different styles of editing I use almost become like a “three-act structure” that changes the story’s tempo and style. In a way, I feel like I’m making, like, three movies in one short film, like with People on Sunday, for example, with all these varied editing techniques. So the editing styles not only vary from film to film, but within the films themselves.

LC: There is a recurring interest in internet culture—like YouTube, ASMR videos, stuff like that—present in your films. Considering social media and readily available camera equipment, it seems like everyone is making their own image-based world, gesturing towards a shifting relationship between human subjects and images.

TS: There are two main things. I think one thing is an innate desire to create a new image, which leads to the question of why I want to do so. Why do I have to produce another kind of image? What is this urge?

On the other hand, I am also interested in re-appropriating the existing aesthetics of internet culture or contemporary culture as a way for me to add another layer, another thought, to the social dynamic. Within the context of People on Sunday, the use of ASMR and online therapy videos is a way for me to think through ideas of “self care.” I think it’s related to the contemporary conception of work and rest because it’s paradoxical, in the sense that self-care has also become work but isn’t recognized as work. It’s also tied to how mental-health struggles become individualized—neurochemical imbalances are no longer understood as a product of an exploitative system, but rather internalized as strictly personal. The cure then becomes one of “self-improvement” or “self-care.” You can see these layers in Squish! (2021) and People on Sunday through the re-appropriation of these forms of online therapy videos.

Again, I’m also intrigued by a lot of homemade video clips because of this tension between leisure-work and non-work. Like you said, cameras are very accessible and people are starting to become their own producers. It feels like self-exploitation or auto-cannibalization in a way, but in a very cute and optimistic sense, which is kind of scary to me. The feeling that you can have your own power to create things, create your own film, anything. It’s a question of the subject feeling free, yet under the yoke of a preset protocol or modality that influences the image or video you make—so, another paradox.

LC: The production of these images is executed under a framework of self-disciplining or self-exploitation yet pre-figures a classical boss-worker relation, in that one is not waged. Of course, this isn’t true across the board, but many people produce these videos under the pretext that if they keep plugging away, eventually they will get rich or they will get famous.

TS: That’s a very explicit example, but there are implicit ones as well. For example, I am a very lazy person, and under many contexts I can’t simply state this [laughs]. I have to pretend to have a hustler’s mindset. In a sense, this is another example of self-fashioning or even image-making.

LC: Do you have any personal relationship to the clips you re-appropriate, or do you use them because you think of them as emblematic of a contemporary cultural or aesthetic zeitgeist?

TS: Some of those pieces of “found footage” are actually staged by me. The clips are a sort of footnote to the film, so that there isn’t too much “text” in the film, which can risk overwhelming the audience. When I use montage, these sections of spliced footage offer a kind of image-based subtext.

LC: Does People on Sunday have any citational relationship to William Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm (1968)? It’s a film where a film crew films a film crew filming a film. The original concept for the movie ended up getting heavily modified, but the original concept for Greaves was to film actors trying to get an acting job, and in general, trying to produce a film that portrays “reality” rather than the heavily mediated filmic forms normal to Hollywood. Funnily enough, he tries to get at this idea by creating a film within a film within a film.

TS: I actually haven’t seen the film! I have gotten this comment before though, I want to see it. The reason why People on Sunday feels like a film within a film is that I was skeptical when I watched the original People on Sunday (Robert Siodmak and Edgar G. Ulmer, 1930). For context, it’s an early melodrama about amateur actors, who, in the film, possess those same jobs, and usually meet on Sundays to hang out. When they were making the film, the actors would meet on Sundays to shoot the movie, and the opening title card notes that the cast has since returned to their jobs. My version of the film follows this same sort of inquiry: What is it to act in a way that communicates non-acting?

This question is the reason I chose to make a film about film. My version speaks to the accessibility of cameras and images, but also to the way in which we’re always performing in a world of widespread surveillance. I linked these ideas to that of cognitive labor and the dream of becoming an entrepreneur—to be able to work anywhere or anytime.

LC: The impact of imagery on our behavior as an embodied experience I think expands, again, with the prevalence of cameras. It extends beyond the selfie stick or the phone camera, to even mass surveillance. When you know you’re on camera, you act differently.

TS: Even worse, when you are conscious that you are on camera all the time, what happens to your sense of yourself as a subject? You become less of an individual. You become almost like a part of something else, always. It’s very disempowering.

LC: Could you talk about gendered labor in your films? This comes up most prominently in Klai (2011), but also in Squish! and A Room With a Coconut View where even a disembodied AI is female and cast as hospitality labor. This historically gendered construction of labor is also extended into digital space.

TS: Many times while I’m making a piece of work, I tend to give a lot of importance to emotional, cognitive, and free labor, also to how one has the indirect and invisible kind of pressure to perform as “oneself.” Gendered labor has manifested in a different way in each work. When I made A Room with a Coconut View, I learned that in order to use a Thai AI voice, the only available option is a female one. So the character Kanya ends up reflecting the underpinning ideas of orientalism and patriarchy. In Squish!, the narrator’s voice is female because often in animation, the character of a young boy or child is dubbed by a female voice, and not the other way round. I find that gender ambiguity—its slippage and double layering—accentuates the role that the character is assigned, while its vagueness also opens up other possibilities to think about the character, I hope. Talking about this also made me think of one of the characters in People on Sunday, the one who shoots behind the scenes. For that character, I also deliberately intended to have a male voice who confesses his chronic depression.

LC: Just for fun, what are you reading right now?

TS: I just finished reading The Ontology of the Accident (2009) by Catherine Malabou because recently I’ve been curious about the brain and I really like her writing about plasticity, which I think is going to be somehow in my new project because it kind of answers some of the questions that I feel like I had in my previous work, namely about how every frame leads to another frame. The precept of rationality is very fixed, so in this sense, I find her writing interesting in regards to many of the concepts I have been working with. I’ve also been reading Ottesa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018). I feel like she knows me [laughs]. I have to relax.

LC: Now that we’re talking about Otessa, I’m curious if you also have any considerations or interest in the role of behavior and its relationship to emotion-regulating drugs, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, etc. You hint at it in People on Sunday but it also comes up in our conversation—this vicious cycle of intense alienation, the psychological fallout of labor, and self (image) production under capitalism, then the turn to mood stabilizers in order to keep working—work being, very often, the thing that starts the cycle off in the first place.

TS: That’s it—it’s a vicious, irrational circle. It’s kind of like how an image is framed, and what is left out. For example, if you are diagnosed with a psychiatric disability, you could go to the doctor and they might frame it as a chemical imbalance. But we live in a networked society, surrounded by people and systems. There are other parts to it that the doctor cannot get at. Going back to the idea of framing, we can see how the frame has a political agenda. It’s not only that depression is hard to treat, it also has something to do with productivity and how a person can be exploited. But because of what is left out of the frame, the norm becomes, “Go fix yourself before you come back to the factory.”

-

For more information contact program@e-flux.com.

Program

Part Three

Screening: On trash collectors and Michael Jackson impersonators

With RUTMEAT, Tulapop Saenjaroen, Jia Zhangke, and Zheng Yuan

July 3, 2022, 7pm

Part Two

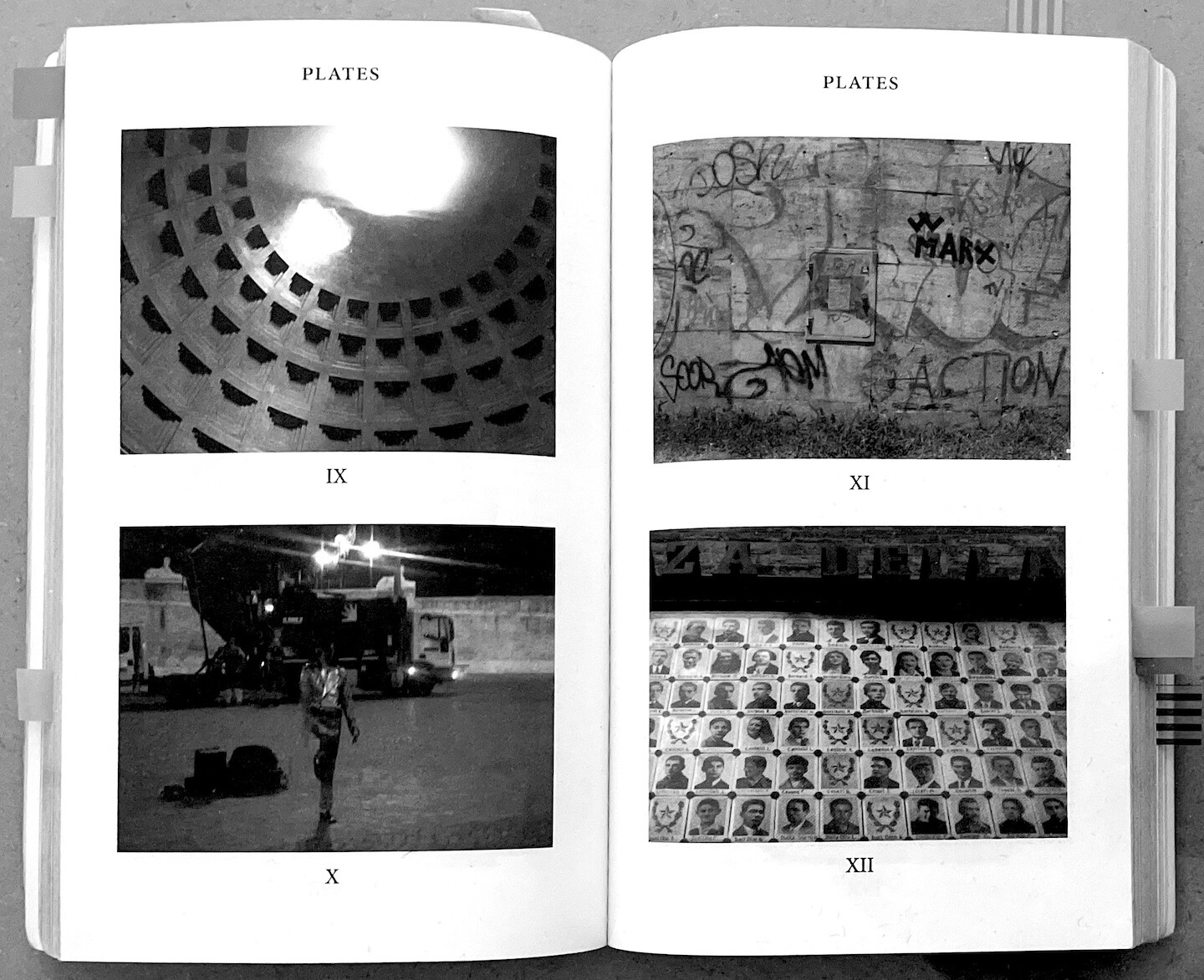

Reading: Evan Calder Williams, Roman Letters

With Anahita Jamali Rad and Steff Hui Ci Ling

July 1, 2022, 9pm

Part One

Screening: On floating and eating

With Kelley Dong, Tulapop Saenjaroen, Anocha Suwichakornpong, and Zheng Yuan

July 1, 2022, 7pm