Unreformable: Week #5

¿Quién puede matar a un niño? (Who Can Kill a Child?)

Narciso Ibáñez Serrador

1976

111 Minutes

Courtesy of EGEDA

Artist Cinemas

Date

Streaming till November 30

An English couple land on an island inhabited by children who have developed superpowers after having been subjected to war. The couple come to discover that the children have killed all the adults on the island and that they are next.

The film is presented alongside a text response by Dora Budor.

¿Quién puede matar a un niño? is the fifth installment of Unreformable, an online program of films and accompanying texts convened by Adelita Husni Bey as the eighth cycle of Artist Cinemas, a long-term, online series of film programs curated by artists for e-flux Video & Film.

Unreformable runs in six weekly episodes from October 18 through November 28, 2021, streaming a new film each week accompanied by a commissioned interview or response published in text form.

On Narciso Ibáñez Serrador’s Who Can Kill a Child?

Dora Budor

“The worst is that the children are always the ones that suffer the most,” says the seller at the photo equipment store to the young British couple who have just arrived at the coastal tourist destination of Benavis. The comment arrives after they catch a glimpse of the television news announcing that Thailand has fallen to a fictional Communist uprising. The news on the television sets the film in the quasi-future tense, which, however, remains the only temporal signifier that we may not be in the real “now”—on the Mediterranean coast in the mid 1970s—at least until you try to google the popular tourist destinations of Benavis and Almanzora in Spain, and find out they do not exist. As the sense of the simmering apocalypse slowly fills the air, that revelation doesn’t come as a surprise.

The late Uruguayan-born Spanish film director Narciso Ibáñez Serrador’s Who Can Kill a Child? (¿Quién puede matar a un niño?, 1976) is prefaced by a graphic overture of a variety of archival black-and-white war footage intercut between the credits’ red lettering and children’s lullabies and chuckles. A long newsreel of various twentieth-century atrocities unravels through the first eight minutes of the film—from the camps of Auschwitz, the civil war between India and Pakistan, the Korean and Vietnam wars, and Biafra—with the emphasis on children en masse as the innocent victims. The intro, in a less-than-subtle way (that will color the interpretation of the rest of the film), sets the premise that a certain historical relation will be played out between the innocents and the adults for the suffering the adults have imposed on children.

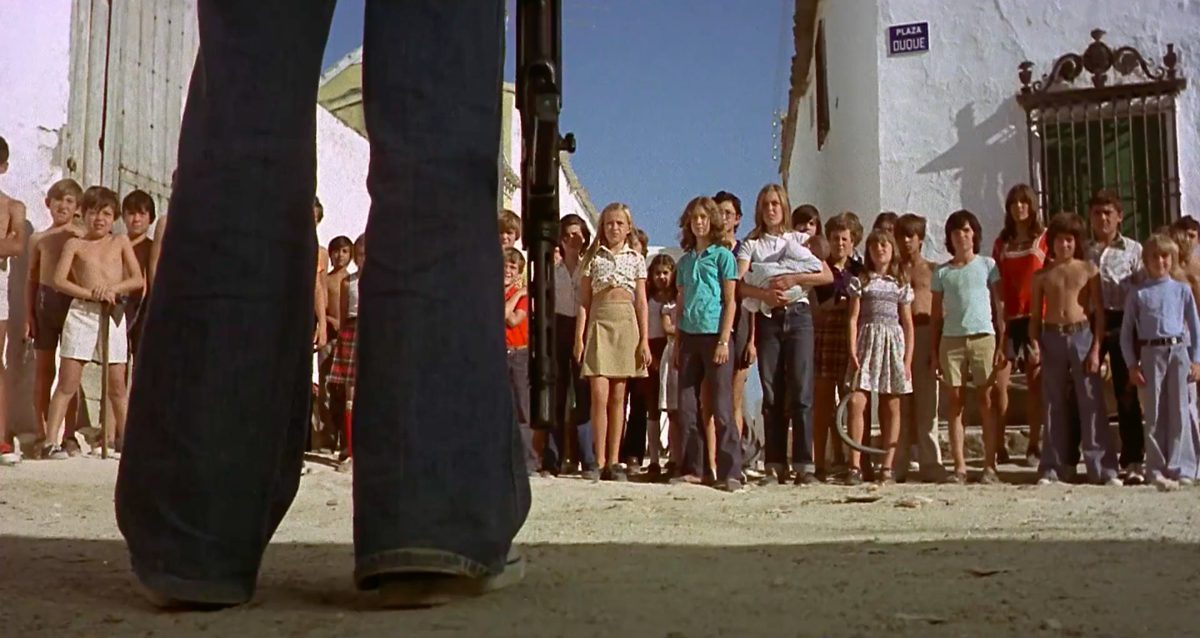

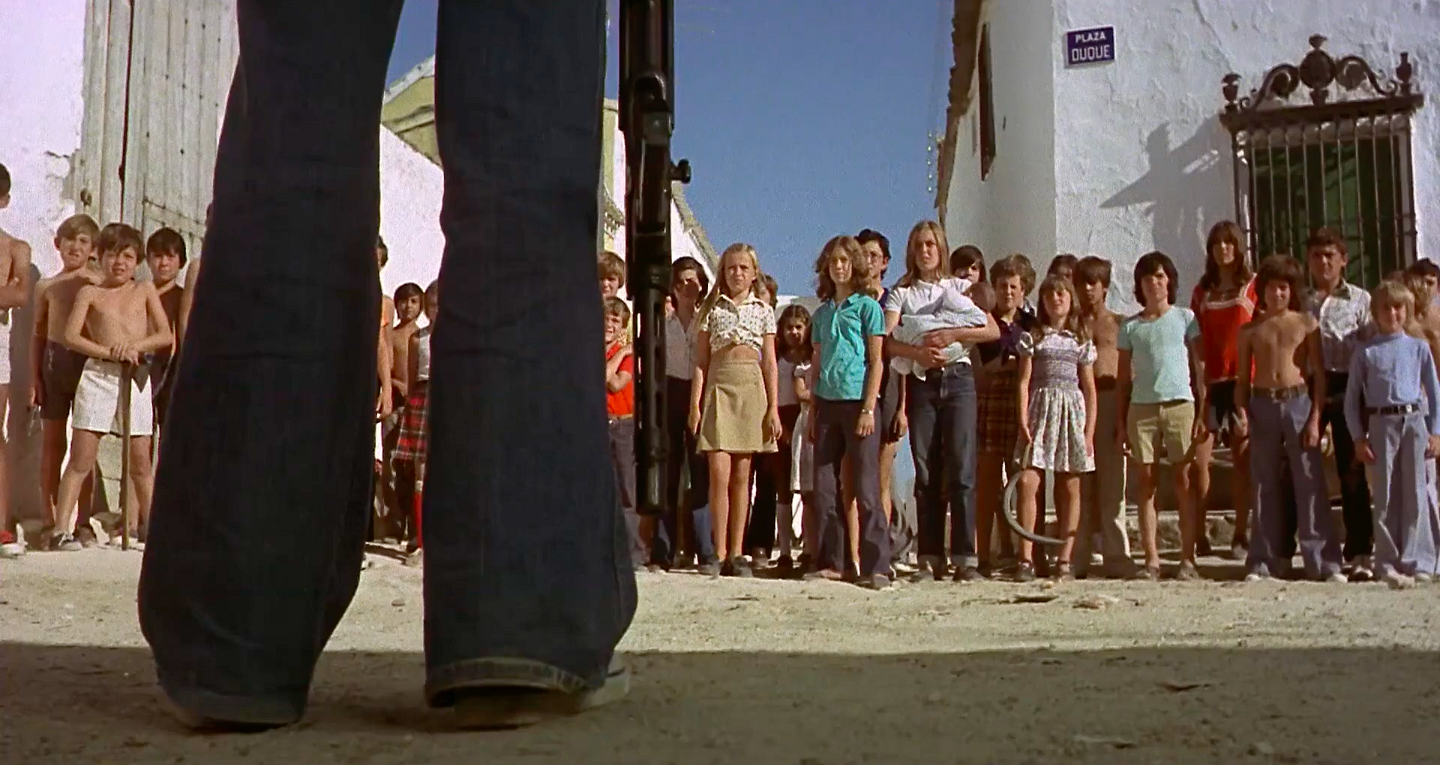

As soon we arrive to the postcard-like scene of Benavis beach brimming with tourists, the camera switches to full technicolor. A woman has been dragged out of the seawater by paramedics after a strange stabbing incident, prior to the arrival of the film’s main protagonists, tourists Tom (Lewis Fiander) and Evelyn (Prunella Ransome). The English couple are seen arriving by bus; this will be their last vacation before Evelyn gives birth to their child, an event that Tom, as we find out, is still unsure about. As the couple look around and mingle with the street crowds, the sky fills with noise and the fireworks of fiesta, whose blasts allude to the war explosions earlier in the film. The couple spend the night in Benavis before departing to the remote fishing island of Almanzora the next day. Upon their arrival, a group of children is seen playing and fishing in the bay. Everything is weirdly, menacingly silent. The children smile and stare mysteriously, but don’t respond when spoken to.

The film operates in a similar vein to William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies (1954) and to Colombian-Ecuadorian director Alejandro Landes’s recent war drama Monos (2019) about child guerilla fighters, but even more so to the lesser-known Emperor Tomato Ketchup (1970)[1] by Japanese director Shuji Terajama, about an agonzing battle between two boy-generals playing a never-ending game. Connecting these works is a rare portrayal of children as genuine threats, who take over the role of adults as perpetrators of relentless cruelty and horror. Serrador’s schlocky horror challenges the very image of innocence. Tom and Evelyn soon learn that the children are not only capable of violence, but have remorselessly murdered just about every adult on the island; that they are capable of communicating with each other telepathically, forming a collective body and mind. The exact reason for their homicidal behavior remains unknown, except that they are set on eradicating the entire adult population. Yet, the adults are mostly unable to defend themselves, proclaiming the words that give the film its title.

To show children as unchecked adults—as killers, as unruly mobs—crosses an unspoken boundary that is profoundly taboo, unless their behavior can be attributed to demonic possession or satanic parents. The central horror of Who Can Kill A Child? alluded to by the opening credits is the acceptance of state violence and decisions made by governments that will inevitably kill millions of innocent children, yet continue their path in the world without alteration. The children thus abandon the image of innocence imposed upon them by the very same adults who subjected them to abuse throughout history, rebelling against them with the same atrocious violence.

The romantic notion of the “innocent child” did not exist before the modern age. As Anne Higonnet[2] argues, the fantasy of the Child became a cultural obsession during the Renaissance, with the notion of the inherent innocence of the child starting to rise in seventeenth-century Europe, which also saw a proliferation of images of children in art. According to Viviana A. Zelizer,[3] the end of the eighteenth century saw an explosion of emotional and sacral value placed on children, with the concept of the “useful” child expected to make a valuable contribution to the family economy gradually giving way over the course of the nineteenth century to the “useless” child of the twentieth century we have inherited today: economically worthless yet emotionally “priceless,” valued primarily for its innocence, and praised for its lack of both, skill and the capacity for judgement.

1900s child-labor legislation in the US, as Zelizer continues, involved a long, delicate process of drawing distinctions between legitimate and illegitimate forms of work. One of the most controversial aspects of the discussion surrounding these legislations centered on child actors. Despite opposition from anti-child-labor purists, acting was consistently recognized as a legitimate form of work for children because of its “playful” nature. Zelizer notes that the special dispensation given this class of child-workers reflected the sentimentalization of childhood. “Ironically, at a time when most other children lost their jobs, the economic value of child actors rose precisely because they symbolized on stage the new economically worthless, but emotionally priceless child.”[4]

In Who Can Kill A Child?, the most disturbing scenes stem from sentimental images of children frolicking that rapidly switch to these seemingly powerless outcasts’ chilling outbursts of violence. Still playful—as if the children were revolting against us, or against the established orders of cinematic representation.

[1] In Emperor Tomato Ketchup, children brandishing rifles enforce martial law, cavort with prostitutes, and hunt for adults in hiding. The prototype for the film was Terayama’s 1960 radio play Otona-gari (Adult Hunting), condemned at the time by civil authorities for its subversive sexual agenda and incitement to revolution (it was styled as an emergency news report that claimed young children were carrying out an insurrection in Tokyo).

[2] Higonnet, Anne. Pictures of Innocence: The History and Crisis of Ideal Childhood (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1998)

[3] Viviana A. Zelizer, Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children (New York: Basic Books, 1985)

[4] Ibid, p. 96.

-

Dora Budor (b. 1984, Croatia) is an artist and writer based in New York. Budor has exhibited extensively throughout the U.S. and Europe. Her recent and upcoming solo exhibitions are at Kunsthaus Bregenz (2022); Progetto Space, Lecce (2021); Kunsthalle Basel (2019); 80WSE, New York (2018); and the Swiss Institute, New York (2015). Her work has been presented in group exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Palais de Tokyo, Paris; the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and at the 9th Berlin Biennale (2016); the Vienna Biennale (2017); the 13th Baltic Triennial, Vilnius (2018); the 16th Istanbul Biennial (2019); the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (2020); among other institutions. Budor was a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship for 2019–20.

For more information, contact program [at] e-flux.com.