When I was a child, I was told that when people died they became stars. I didn’t really believe it, but I could appreciate it. We three Red Army soldiers wanted to become Orion when we died. And it calms my heart to think that all the people we killed will also become stars in the same heaven. As the revolution goes on, how the stars will multiply!

—Közö Okamoto, interview in Israeli prison1

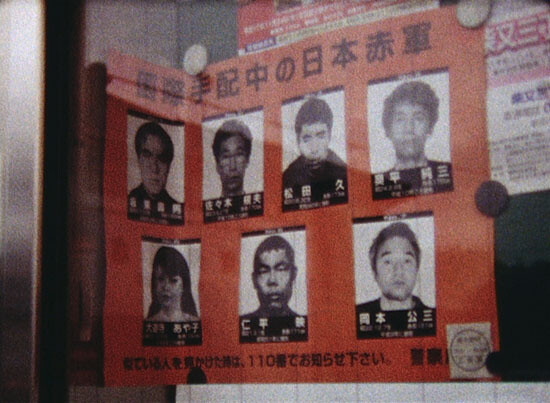

The news item was nondescript.2 In a four-sentence summary, a Japanese news service announced that Osamu Maruoka, “former Japanese Red Army member,” died in the prison hospital at age sixty. A year earlier, he had unsuccessfully appealed for a suspension of his sentence on the grounds that he suffered from a serious heart condition.

The report included a brief précis of his life achievements, mimicking bullet points in a resume: a) Conspired with Palestinian guerrillas in hijacking a Japan Airlines plane over Amsterdam in 1973, b) Hijacked a JAL jumbo jet over India with four accomplices and forced it to land in Bangladesh in 1977, and so on.

The circumstances of Maruoka’s arrest were quotidian: he was apprehended in Tokyo in 1987, when he entered the country on a forged passport. I had been tracing the eleven JRA members who had been on board a hijacked plane that flew from Dhaka to Algiers in 1977, and nondescript finales were the norm. In the recordings of the negotiations between the lead hijacker (codename: “Dankesu”) and the hostage negotiator (Air Force Chief A. G. Mahmud), the hijackers (four initial companions, and six who were released from Japanese prisons as part of a hostage exchange) remain an obstinately ghostly presence.

Bangladeshi Journalist: How many hijackers were on board?

Japanese Stewardess 1: Five … past … five men.

BJ: Did you see their face?

JS1: fes?

Japanese Translator: Fays! Face! (mimes)

JS1: Yes, but, (mimes) covered. Covered.

BJ: Could you guess if they are young or old or middle aged?

JS1: About …

Japanese Stewardess 2: They said … about, (shows two fingers) about two … twenty years

BJ: Very young then!

JS2: No, the youngest and the oldest, twenty, about twenty years … difference

JS1: About thirty years

BJ: Between 30–35, 25–35, or 25–30?

JS1: Yes

BJ: Which one?3

The 1977 hijacking was fastidiously followed in the Japanese and Bangladeshi press, but after the hijackers arrived in Algeria, very few traces were left behind—only fragments from such moments of mistranslated or fetishized details remembered by a hostage: “cruel eyes, he had very cruel eyes, I can’t remember anything else.”4 Only at the time of arrest did things come back into focus. Maruoka had been arrested in 1987 on a false passport; another member had been arrested while shoplifting dried cuttlefish in a Tokyo store. The computerized system in a Tokyo police station had matched his fingerprints with an Interpol database. An international hijacking career ended over a craving for salty snacks.

Maruoka could possibly be the lead hijacker of that Dhaka flight—codename “Dankesu”—on the negotiation tapes. In the last moments of the hijack, he insisted on staying doggedly illegible:

Mahmud: Danke … uh, tell me what is your name? Because I have told you my name.

Dankesu: My name is … number twenty. When we establish people’s republic of Japan, I’ll tell you my original name.5

If number twenty was Maruoka, he died in prison in full view of the state. But he left little in the way of records that could help a researcher trace the origins of this group, or create any social mapping of its membership. The experience of the JRA in captivity stands in marked contrast with that of Rote Armee Fraktion (RAF), whose time in Stammheim prison was exhaustively documented on television and in print. Along with recent film adaptations and academic monographs, fragments of the RAF’s own archives keep trickling out, from Meinhof’s early articles to Astrid Proll’s collection of photographs.6 It has been noted more than once that RAF members, children of a particular conjuncture of media-is-message moment, always had one eye on the record for posterity, documenting themselves within their own process. The cursory brevity of Maruoka’s obituary highlights the fact that no similar self-generated archive exists for the JRA—certainly not in English. Four very different works about the group provide incomplete snapshots, with Eric Baudelaire’s film coming closest to holding the ethnographer’s gaze on group survivors.

Think Tank Identikit and “Salaryman” Japan

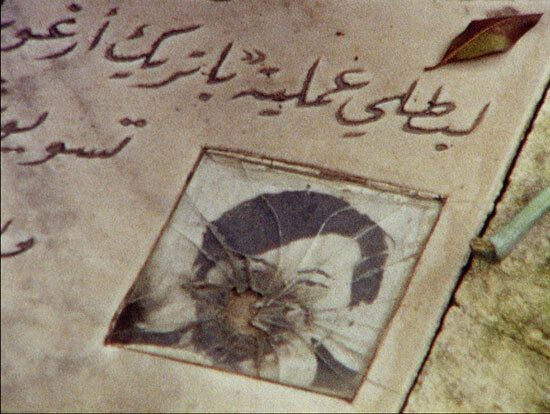

William R. Farrell’s Blood and Rage is almost a penny dreadful, but it is still quite useful as an example of the terror-industrial complex’s publication flow. His interest in the Japanese Red Army is primarily to probe the mind of the “modern terrorist,” by now a commodity fetish object. Written in 1990, it begins with breathless warnings (“We will hear more from the JRA. The noise will be loud and the effect deadly.”7) that come, rather pointlessly, long after the group’s demise. The book’s acknowledgments lay out the think tank network that Farrell’s text relies on: the Institute for Social Engineering in Tokyo, the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies in Tel Aviv, Business Risks International in Nashville, and the Naval War College in Rhode Island. The last organization seems an anomaly until we read in Farrell’s first chapter that in 1988, JRA member Kikumura Yu (“more like a ne’er do well than an agent of death,” says Farrell) was arrested on the New Jersey Turnpike. During the trial, it was alleged that Yu’s target was the US Naval Recruiting Station in New York, which explains how the Naval War College library came to build up an extensive Japanese-language dossier on the JRA. These sources guide Farrell towards a highly pathologized view of the members’ motivations. Even Yu’s diminutive presence (“5 feet 2 inches”) is cause for Farrell’s droll witticism that this man had “planned to stand tall” in the annals of terrorism.

Although two of the JRA’s most notorious actions are the Lod airport killings of 1973 and the Dhaka hijack of 1977, most analysis of the group centers around the Asama mountain killings of 1971. A Grand Guignolmoment of group hysteria, the incident began with JRA members hiding in the mountains for training and “self-purification.” The group had been weakened by arrests that decimated top leadership, and the isolated mountain was the stage for a series of recriminatory self-critique sessions. The leaders turned on the weaker members, accusing them of being “insufficiently revolutionary.” Sexual desires for other members, whether expressed or silent, were also seen as betraying the movement. Ritual beatings were inflicted on the accused weaker spirits, and if a comrade died from this, it was considered haibokushi, or “death by defeatism.” Eventually, the JRA killed a dozen of its own members at this isolated lodge. Newspapers dubbed it “revolutionary suicide.” When the JRA members were later arrested in a police dragnet, the discovery of the dead bodies sent shock waves through Japan. Asama became the overdetermined basis for all understandings of the JRA group and its motivation, usually read as group-induced pathology and sexual competition.

Farrell’s analysis of the “bastard child”8 Japanese Red Army is closely aligned with the commonly held psychoanalytic view in Japan that Asama was primarily an expression of repressed sexuality. We see this projected outward to the group’s post-Asama arc as well. Individual cell leaders are stand-ins for group dynamics, and Farrell spends a great deal of time looking into the autobiography of the more “disturbed” members, such as Nagata Hiroko.9 For his descriptions, Farrell depends on Japan Times reports of March 1972, which were published as part of a media push to present caricatured images of all JRA leaders. The Japan Times in particular focused on the rage that Nagata directed at female JRA members at Asama, and concluded that she was a “mentally unstable, radical queen.” Farrell discards the closeted queer theory and focuses on the ravages of hetero lust as a foundational moment in Nagata’s psyche. He details the 1969 encounter between Nagata and her onetime mentor Kawashima Go. Visiting the arrested Kawashima in prison, she berates him for his lack of revolutionary zeal—an encounter later leaked to the press by the prison guards. Farrell quotes from post-Asama press reports to argue that Kawashima had raped Nagata on their first encounter, after which they eventually became lovers. He was, in Farrell’s words, “a lover who took, not shared,” planting a traumatic experience in Nagata.10 It is this trauma that allegedly leads her to becoming an instigator of violence within the JRA, first through “sexual experimentation” and then, ultimately, “revolutionary zeal.”

From Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman’s Empire of Trauma, we know that Farrel’s working definition of trauma is aligned with early-twentieth-century theories of the weak-willed receptor. Farrell’s dependence on military institutions as his interlocutors privileged this view of certain people’s natural receptiveness to traumatic events (hence the emphasis on Nagata’s puberty travails). Before the rise of micro-scale urban guerrilla warfare, as well as the memorialization of natural disasters, trauma was most frequently observed during industrial accidents and in the theater of war. Forensic psychiatry, which previously had been focused on the evaluation of criminals or “abnormal” inmates, looked to the detection of trauma neurosis as an expansion of their field of expertise. Pierre Janet argued that trauma arose from an external shock (perhaps an event in early childhood) that created a mechanical psychological reaction (versus the neurological anatomical reaction proposed by Jean-Martin Charcot). Freud developed his theory in two stages that were distinct from Janet (who focused on external shock). In the first variation, which Freud called seduction theory, he argued that hysteria was generated by a sexual trauma in infancy. Later, Freud abandoned seduction theory and moved to fantasy theory, which argued that the sexual is already traumatic in the unconscious.

In Farrell’s book, we find a mixture of Janet’s external shock theory (e.g., Nagata’s reception by classmates, the rape by a comrade) as well as Freud’s sexual as already existing trauma. He states that “sexual behavior was very much on the mind” of JRA leaders, delineating a rupture between two group factions after massive police actions (the JRA had formed from the wreckage of two other radical groups). One JRA faction argued that women were to be supporters, sexual and domestic, while men did the “soldiering.” The more radical JRA faction, led by Nagata, argued that sexual relations had to be subservient to the movement, and engaging in such relations was counterrevolutionary. Finally, Farrell uses the beating death of Shindo Ryuzaburo, accused of flirting with female JRA members, as evidence of repressed sexuality as a prime mover of JRA energies.

Sociologist Patricia Steinhoff goes beyond Farrell’s tabloid-like analysis of puberty crises. Instead of responses to an external trauma in childhood or puberty-onset sexual misadventures, Steinhoff focuses on the Japanese corporate ideal type (“Sararīman,” or salaried man) as the model to understand the violence of the JRA, especially the confrontation at Asama lodge.11 It is this socialization itself that she identifies as the root of their violent subjectivation. In the Althusserian interpellation story, the act of naming can only attempt to bring the addressee into being—there is always the possibility of mishearing, refusal, or defiance. So, why the turn and why the obedience? Steinhoff’s rather simple answer is that young Japanese people are socialized into being model employees of corporations. She argues that rather than being misfits at the margins, the JRA recruits were socialized normally, and this is what made them ideal candidates for the breakdown—leading to fratricide in search of “purity,” along with other acts of violence during a decade of hijackings.

In a fairly essentialist analysis, Steinhoff regards the internal structure of the JRA as a reinvention of the Japanese managerial style. She highlights two specific ideal salaryman attributes that the JRA espoused; at the same time, because of underground status, the JRA did not absorb these elements fully, leading to contradictions that would implode group dynamics. These attributes are the JRA’s strong hierarchical structure, and its rituals that emphasized membership. In the case of the Rengo Sekigun (United Red Army)—the new group that was formed from the merger of two different organizations (Sekigunand Kakusa)—hierarchies were maintained, but not without dispute. Sekigun leader Mori Tsuneo became the head of the new group, while Kakusa’s leader Nagata Hiroko reported to him. According to Steinhoff, such a hierarchy is generally acceptable in Japanese society, but because of the “revolutionary” nature of the JRA, Nagata felt compelled to reject gender roles and push against this hierarchy. For Steinhoff, the planning and decision-making process was “characteristically Japanese,” especially the use of autonomous groups, the obsessive degree of detail in event planning, and the implementation of systematic procedures to maximize “learning from failure.”12

Although replicating the Japanese corporation within the secret cell, the JRA, as Steinhoff reminds us, lacked a standardized output, a stable site, and social acceptance, and was therefore plagued by inter-member conflict. Steinhoff emphasizes that in conflict situations, it was precisely standard “politeness” that aggravated the dispute. The technique of breaking down unproductive defenses, by making the person acutely aware of them in a group consciousness exercise, was practiced in American group psychotherapy; Steinhoff argues that the same model was being implemented in the JRA.13 However, the lack of any trained practitioners of psychotherapy made the JRA lose control of the process. Thus, when Nagata berated member Toyama Mieko for her “feminine demeanor,” only to have Toyama remain silent in a display of “standard polite Japanese response,” Nagata was compelled to continue with more fervor. Steinhoff argues that members may also have been trying to display amae (seeking favor by creating a relationship of dependency), even though the Japanese student movement of the 1960s (which gave rise to some parts of the JRA) had already rejected amae as antithetical to a “revolutionary spirit.”

Steinhoff’s analysis depends on a very particular essentialization of “Japanese politeness,” as well as conflations of various analytic models. On the one hand, we are told that the JRA network was a faithful replication of the Japanese corporation. On the other hand, the network is supposed to have been infiltrated by American group therapy techniques—an “alien” practice that “Japanese politeness” could not digest. Steinhoff is on firmer ground when discussing conceptual innovations developed in response to member defiance. For instance, Mori was the innovator of the concept kyosanshugika, which translates as “communist transformation” or “communization.” This term had first been used in Sekigun’s written material (“communization of revolutionary soldiers”), but no practical steps had been defined for reaching this. The JRA’s time in Asama led to the design of kyosanshugika as relentless self-critique sessions. According to Steinhoff, fuzzy thinking was in evidence among both leaders and followers—the former innovated in new, illogical ways and the latter followed without questioning. Mori had, by this time, fused together two terms: jikohihan (self-criticism) and sokatsu (collective examination of organizational problems). The emotional appeal of transformation “from bourgeois Japanese college student to revolutionary soldier” made all aspects of past life or present thought suspect. Just how much self-criticism would be needed before sokatsu could transform the organization? Unfortunately, the organization, or in this case the individual bodies, could not survive the examination process. Steinhoff thinks the “traditional Japanese practice of decision making by consensus” doomed the process, as no individual follower could take control of the situation and call for a halt to kyosanshugika.

Pink Remediation and L’Anabase

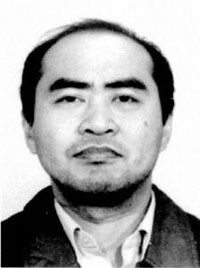

Farrell and Steinhoff represent two highly schematic ways of looking at the Japanese Red Army. One gives credence to tabloid reports of childhood trauma, while the other maps the movement onto a corporate organogram gone awry. Both authors focus on the arc that begins at the Asama lodge and ends with the airport events. The Lod attack, described as the “first suicide mission in the history of the unfolding Mideast conflict,” exerts a magnetic pull on historians.14 The JRA also presented it as a central event in their redemption as a world revolutionary group. The violence of Lod erased the public shame of the mountain fratricide, and by carrying out the action in the name of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the JRA catapulted themselves into the center of a global network (which included Rote Armee Fraktion and patron governments at the various nodes).

Filmmaker Eric Baudelaire pushes against this narrative skein that begins and ends with the JRA’s dramatic plane hijackings. Instead, he traces what happened to the JRA in the aftermath of the 1970s, long after the television cameras had left, and Arab governments had lost interest. In many cases, the host countries were aggressively exploiting the JRA as an example of the global reach of the Palestinian struggle—both to redirect domestic dissent, and to claim leadership of a post-Bandung amorphous idea of deterritorialized globalist movements. Young members of JRA were thrust into the role of being figures for a transnational movement; but once the euphoria of the event had faded, they were often adrift in their new host countries. One of the early hijackings that involved ransom money was the September 1974 takeover of the French Embassy in the Hague. After a crisis lasting several days, the hostages were released in exchange for a $300,000 ransom. The JRA then tried to fly to Yemen, but were refused permission to land and eventually had to settle for Damascus. The Syrian government received JRA members cordially, but immediately informed them that hostage taking for money was “un-revolutionary.” The money was seized, but where it went no one seems to know. By the time of the 1977 hijack in Bangladesh, the ransom had risen to $6 million, which was dutifully impounded by the government at the final destination of Algeria. When you read about JRA members showing up on police radars, alone and penniless, in cities as varied as Bangkok and Lima, you can presume a more general abandonment (not only financial, but also political). This would be accelerated by the Israeli invasion of Lebanon which made it dangerous to offer them refuge. By the mid 1980s, they were revolutionary orphans, bereft of a mission.

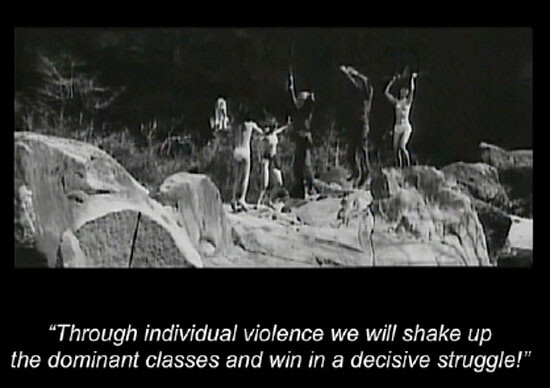

It is this aftermath that Baudelaire is intrigued by, offering the possibility of looking at “revolutionary” commitments after the disappearance of the cause. To explore this, he tracked down JRA member Masao Adachi. Adachi was a filmmaker, and also part of the JRA organizing cell in Lebanon. Until 1971, Adachi was primarily a film director’s assistant, working with renowned “pink” erotic film director Koji Wakamatsu. Both were JRA sympathizers, and the films that Wakamatsu made in this period can be read as erotica that doubled as propaganda. Jasper Sharp’s book on the pink industry describes Wakamatsu’s appreciation of the freedom of the erotica format: “They gave me a free rein as long as it included some shots of women’s naked backs and some love scene.”15 That “free rein” appears to have extended to direct on-screen endorsements of JRA’s tactics of violence.

Yuriko Furahata’s work on Japanese avant-garde film reads Wakamatsu’s films as part of a cycle of intensified “mediatization.”16 This was a period when some of Wakamatsu’s films included newsreel footage of JRA events that occurred the same year the films were made. (Adachi, who was in active communication with JRA members, often collaborated on these films). The speed of this repurposing can be seen in the 1970 film Sex Jack (selected for Cannes in 1971), which drew on the same year’s Yodogō hijacking that had ended with the hijackers defecting to North Korea. The film appropriated the Yodogō hijackers’ slogan “We are Tomorrow’s Joe” (itself appropriating the manga Ashita no Jō), circulating a media reference through the actual event and into a film—the entire cycle taking less than a year before it reached cinema screens. Furahata reads Wakamatsu as working in extreme proximity to journalism around JRA events, and eagerly remediating these into his films. These media appropriation techniques also appear to include self-criticism of the movement—often in plain sight, and not to be explained away as simply an ironic gesture.

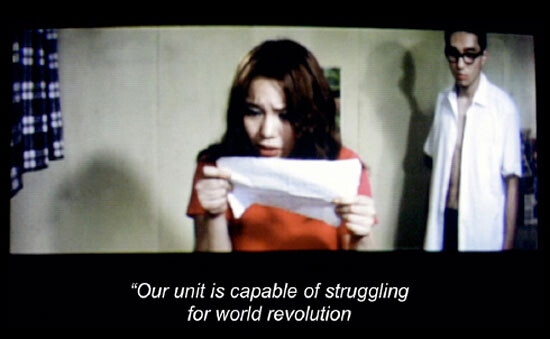

If we venture beyond Wakamatsu’s well-known JRA-inspired films Sex Jack (1970) and Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War (1971), Adachi’s 1969 film Female Student Guerrilla appears to make the self-criticism of the group explicit. Topless Japanese women fire guns at school officials and say they will never return to class because the revolution has started (recalling Lindsay Anderson’s If…). Awash in assemblages of breasts, guns, and slogans, the film could be a spoof of radical chic—except for the fact that a JRA ideologue would surely not satirize the movement. Or, would he? Fast forward to Sex Jack, and in a climactic scene, an underground revolutionary group disintegrates as one member after another takes turns having sex with the two female members. As one woman lies on the floor, submitting to her “comrades,” the other woman, with trembling hands, rapidly reads from a manifesto:

Woman 2: On our own initiative we consciously revoke our own nationality.

Woman 1: [moan] And force our way across the border. [moan] It’s only the beginning. We reject any notion of phases. Our unit is capable of struggling for world revolution and building a world headquarters. Fight on a worldwide scale, spilling into North Korea. [moan] We will grow and progress towards Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Korea, the Near and Middle East. We call on all our Japanese comrades. We call on all revolutionaries. Long live communism. Long live world revolution.17

The scene lays bare the hypocrisy—gendered and otherwise—of the JRA’s revolutionary ethos. But this film was made in 1970, and Wakamatsu and screenwriter Adachi (writing under the collective pseudonym Izuru Deguchi) were still enthusiastic supporters of the JRA at that time. Why did they make a film that seemingly lampooned the group? Why did other JRA members not condemn the film? In fact, how could Adachi become the JRA’s official spokesperson after making this film? Was everyone in on the joke, or is the irony only visible to us today? How do we understand this film when compared to Dziga Vertov Group’s Ici et alleurs (1976), a project more legible as a critique of left violence, made in a moment when hope had not been yet discarded? For the Dziga Vertov Group (Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Gorin, Anne-Marie Miéville), events intervened to bring emotional distance and an ironic doubling to the script. The work on the original film, Jusqu’à la victoire (1970), was interrupted by evets in the region. By the time the Dziga Vertov Group returned to the footage, some of the Palestinian guerrillas they had been profiling had been killed in the Black September war. Facing the chasm between filmed images of inevitable triumph and the ruins of the movement, Godard turned the camera around—questioning the specter of guns that do not fire, and audiences that will a reality into existence. Ici et alleurs is the result: a postmortem of a failed movement whose members have not yet fully absorbed the knowledge of that failure. Are Wakamatsu’s films very different from this, or do they inhabit a similar sense of impending failure? Furahata argues that Wakamatsu’s work carries an element of “belatedness,” where events are recycled, thus allowing the viewer a line of sight into the gap between journalism and cinema.18 I think Wakamatsu expected that the disjuncture would provoke in audiences a cynical eye toward the news cycle, which was usually so critical of the JRA. However, in the scene I described above, the emotional poverty of the group becomes stark, inviting a criticality of claims about revolutionary spirit. What is extraordinary in the film is that the JRA is being imploded from within during their high point—by one of the group’s own ideologues and fellow travelers.

If such premonitions of contradiction appear in a film made when the JRA was at its zenith, how has Masao Adachi navigated the space of revolutionary exile—when failure is much more visible? To explore these questions, Eric Baudelaire tracked down an aging Adachi. Thinking through this space of the stranded protagonist’s exile, Baudelaire introduced the idea of l’anabase, or “anabasis.” The word comes from the Greek, meaning both “to embark” and “to return.” Baudelaire uses it to indicate a “movement towards home of men who are lost, outlawed, and out of place.”19 In his book Le Siècle, Alain Badiou has a chapter on anabasis; he regards it as an allegory of the twentieth century drawing to a close, and of the drifting of a soul caught between two options: “disciplined invention and uncertain drifting.”20 According to Badiou, this idea first appeared in 401 BC, when Cyrus the Young led thousands of Greek mercenaries across the Tigris. During the ensuing battle, the Persian army killed Cyrus, rendering the Greek soldiers suddenly headless, stranded in enemy territory. Their unguided wandering through this unknown land became the plot for the play Anabasis, attributed to Xenophon, a student of Socrates and a professional soldier. Xenophon becomes the protagonist of the play when he is elected rearguard commander after Cyrus’s death. In Anabasis, Xenophon uses the term to also symbolize the collapse of a sense of order after the sudden shift in subjective position from heroic warriors to leaderless strangers in a hostile land. Reviewing the twentieth century use of the term by poets Alexis Leger (under the pen name Saint-John Perse, in 1924) and Paul Ancel (under the pen name Paul Celan, in 1963), Baudelaire suggests that there are two opposed literary motifs at play: a search for home, and the invention of a destiny in a new home.

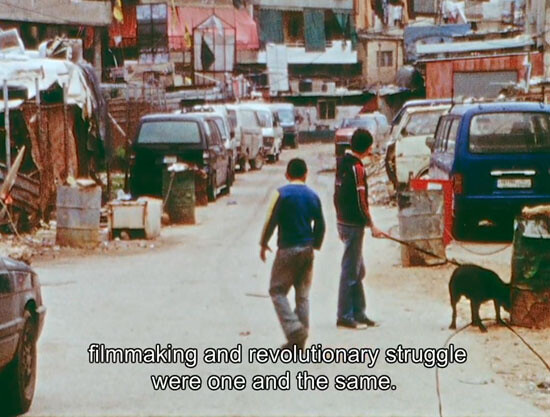

When Baudelaire finally finds Adachi, the JRA member has gone through a second dislocation. After two decades of hiding in Lebanon, improvements in face-recognition technology led to Adachi’s arrest. He was flown to Japan to stand trial, but the court failed to prove that Adachi had a direct role in JRA attacks. He was a spokesperson for the group in Lebanon, but was not involved in violence. The films he wrote for Wakamatsu, with their melding of guns and sex, were not admissible as evidence (They were only fiction, after all.). In the end, Adachi was charged only with forging passports, and he was released from prison after three years. Later, when European interest in Wakamatsu’s films picked up, Adachi was invited to come to a festival in France (this trip would have paralleled his 1971 trip to Cannes, when a stopover in Palestine resulted in the film Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War and led to his stay in Beirut). But, instead of traveling to France, Adachi discovered that the Japanese authorities would not issue him a passport—he was back “home,” but trapped within its borders. Baudelaire’s research leads him to Adachi, but not to an interview in Japan as he expects. Instead, Adachi, who wants to return to filmmaking, asks Baudelaire to help him recover fragments of the Lebanon he can no longer visit: “When you go to Beirut, please shoot some images for me to use in my next film.”

Fulfilling this part of the agreement, Baudelaire makes a trip to Beirut and then returns to Tokyo with 16 mm footage of a changed city, its post-Hariri construction boom rendering the place unrecognizable to Adachi. At this point in the film, the audience may expect to finally be rewarded with Adachi’s recollection of the early days of the JRA: a what-why-how sequence that will give us an understanding of the group’s ideology (a better understanding than Farrell and Steinhoff provide). Instead, Baudelaire presents an elliptical series of encounters in which Adachi mourns his filmmaking life and the loss of Beirut:

Adachi: If I had continued working, I might have been able to make many more interesting films. If I had stayed in Japan without going to the Middle East, I would have shot many more films. But on the other hand, I am a heavy drinker. I might have died from alcohol abuse 20 or 25 years ago if I had stayed in Japan … So perhaps it’s all the same. The question of “here” or “there”—being in Japan or the Middle East, it may be different in a geographical sense, but I think actually there is only one “here.” If you are in the Middle East the Middle East is “here.” Wherever you go, there is only “here.” The point is to pursue a “here” “elsewhere.”21

The film ends here, fading to black. Adachi has brought us back to the unfamiliar familiar—“elsewhere” as a metaphor for the universal. The Japanese Red Army failed to start a world war, a universal insurrection. Many years later, this surviving member seems to want to create a language for a different universal project.

In Don DeLillo’s Mao I, Lebanon’s pious political landscape feels strangely familiar even before we encounter l’anabase: “It is the lunar part of us that dreams of wasted terrain. She hears their voices calling across the leveled city. Our only language is Beirut.”22 Anabasis, or wandering in the hopes of creating, is a theme we glean from the wreckage of movement energies. In the context of Baudelaire’s film, Pierre Zaoui recounts the original story of Xenophon’s Greek soldiers, in chapters that match the path of the Japanese Red Army in the turbulent 1970s: first the initial conflict between thirst for the outside and mercenary interest; then the death of Cyrus and the subsequent wandering in the desert. That wandering was not aimless, but rather a journey that required crime to sustain itself—that is, the routed army needed to plunder to survive. As for the Greeks, so for the JRA, who entered into ever more fragile alliances by the end of the 1970s: Algeria, Syria, Libya, and so on. “Nostalgia for the kingdom of water” drove the sojourners, but when they finally reached home, nothing was as it was promised to be. Adachi realizes that, by the end, the largest collateral damage of the JRA project is its own members. The cities that were the stage for their actions—Dhaka, Tel Aviv, Tokyo, Hague—survived, but men did not. Zaoui reminds us that “Anabasis is not the tale of a ruin of the ruined, but of a ruin of ruiners, or people who are the chief architects of their own ruin.”23

Baudelaire’s film on Adachi encapsulates a bittersweet look at youthful possibilities. This is a reversal of the heroic narrative we expect in these moments—uprisings that do not result in victory for the vanguard. Binary notions of failure/success do not necessarily illuminate, and sometimes even obscure, the optimism that was embedded in these moments. There was an almost impossible belief that a transformation was “just around the corner,” and all that was needed was a “little push.” Though Adachi says little about why he joined the JRA, his thoughts on “elsewhere” hint at why movements choose certain modes of confrontation “in the heat of the moment.” His collaborations with Wakamatsu exploited the anarchic sexual energy of pink film, but were also tinged with the pathos of (possible) failure. That possibility of failure may have even encouraged Adachi and the JRA to push a little faster, a little harder, just to get past the moment of doubt. Adachi’s own earlier film A.K.A. Serial Killer (1969) gives us another lens through which to consider his time in exile. In that film, bleak landscapes draw our attention to the constant vagrancy that shapes the protagonists (and the filmmaker). In Baudelaire, we find echoes of that same landscape, with Lebanon playing itself, but also standing in for Japan, and finally for Adachi– alone without a nation. While we hear Adachi’s voice or read his emails, lingering shots of a highway fade into the horizon. Somewhere on screen, or in the timbre of Adachi’s voice (now hesitant, now certain), is the moment when a foretold failure became the actual.

Patricia Steinhoff, “Portrait of a Terrorist: An Interview with Közö Okamoto,” Asian Survey XVI (Sept. 1976), 842

Kyodo News Service, “Ex-Red Army member Maruoka dies in prison hospital,” May 29, 2011.

Naeem Mohaiemen, United Red Army (The Young Man Was, Part 1), 70 min. (2012), 00:56:14.

Naeem Mohaiemen, Interview with Carole Wells, Los Angeles, March 2013.

Mohaiemen, United Red Army, 01:04:10.

Charity Scribner, After the Red Army Faction: Gender, Culture, and Militancy (New York: Columbia University Press), 2014; Ulrike Meinhof, Everybody Talks About the Weather … We Don’t: The Writings of Ulrike Meinhof (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2008); Astrid Proll, Baader Meinhof: Pictures on the Run, 1967–77 (Zurich: Scalo, 1998).

William R. Farrell, Blood and Rage: The Story of the Japanese Red Army (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1990, xi.

Ibid., 3.

Nagata Hiroko described herself to Japanese police as a “very sensitive person” with parents who “gave her all that she could want.” Farrell argues that the arrival of puberty set off a spiral of self-loathing in Nagata, as her “husky voice” and “slightly bulging eyes” reduced her “femininity.” Nagata compounded this by wearing “wrinkled clothes” and “rarely applying makeup.” Ibid., 4.

Ibid., 5.

According to Steinhoff, the young men and women drawn to become members of the underground group were “quite normal individuals” who were “well-socialized members of Japanese society.” Patricia Steinhoff, “Death by Defeatism and Other Fables: The Social Dynamics of the Renko Sekigun Purge,” in Japanese Social Organization, ed. Rakie Sugiyama Lebra (Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, 1992), 195.

Patricia Steinhoff, “Hijackers, Bombers, and Bank Robbers: Managerial Style in the Japanese Red Army,” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 48, no. 4 (Nov. 1989): 730, 731.

Although Steinhoff does not mention Werner H. Erhard’s EST program by name, it may be what she is thinking of when she compares these JRA confrontations to “consciousness-raising techniques familiar to American women’s groups” (Steinhoff, “Death by Defeatism and Other Fables,” 198).

Eric Baudelaire, L’Anabase de May et Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, et 27 années sans images [booklet] (Centre D’Art Contemporain la Synagogue de Delme, 2011), 12.

Jasper Sharp, Behind the Pink Curtain: The Complete History of Japanese Sex Cinema (Guildford: FAB Press, 2008).

Yuriko Furahata, Cinema of Actuality: Japanese Avant-garde Filmmaking in the Season of Image Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 100.

Koji Wakamatsu, dir., and Masao Adachi, screenplay, Seizoku / Sex Jack, 70 min. (1970). For an extended discussion of Wakamatsu and Adachi’s films: Go Hirasawa, Koji Wakamatsu: Cinéaste de la Révolte, Imho, 2010; Go Hirasawa, Masao Adachi: Le bus de la révolution passera bientot près de chez toi, Rouge profond, 2012.

Yuriko Furahata, Cinema of Actuality, 114.

Baudelaire, L’Anabase de May… [booklet], 28.

Alain Badiou, Le Siècle (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2005), 121. (Excerpts translated by Eric Baudelaire.)

Eric Baudelaire, L’Anabase de May et Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, et 27 années sans images [film] 85 min. (Centre D’Art Contemporain la Synagogue de Delme, 2011), 01:21:00.

Don DeLillo, Mao I (New York: Penguin Group, 1991), 239.

Pierre Zaoui, L’Anabase de la Terreur: vouloir (ne pas) comprende, trans. Matthew Cunningham (Centre D’Art Contemporain la Synagogue de Delme, 2011), 45.

Thanks: Gil Anidjar, Eric Baudelaire, Go Hirasawa, Rafael Kelman, Michikazu Matsune.