What if, in the tech world, there is no next big thing? First we had fire, then came the wheel, and the PC, then the internet and then Google and then the iPhone and then … that’s it. There’s nothing more left to come. We’re waiiiiiiting—but no, we’ve received all there’s going to be and tech’s broad strokes have all happened. Does this sound scary, or kind of sad? We can laugh at such a proposition because we know it’s not going to happen. We might dream of a year when people would just stop inventing new things, but in reality there’s going to be more and more new stuff. All of us will continue our lives permanently vibrating on the tech revolution’s vertical asymptote—screaming like Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby, mid-coitus with the devil: “Oh my God, this is really happening!”

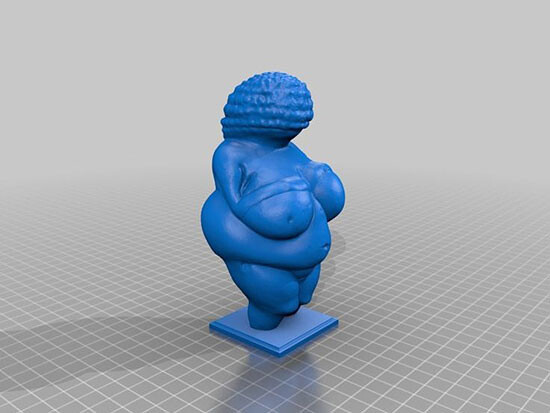

Let’s look at the art world and ask the same question: What if there’s no next big thing? There was the Venus of Willendorf and Picasso and Duchamp and then Warhol and then came a hundred thousand highly defended micro-niches so microscopic that they make sense only when looked at in aggregate, like a mole of carbon dioxide molecules or a computer model of butterfly migrations in and out of Mexico: “The Emergent Behavior of Early Twenty-First Century Contemporary Art.” What if the micro-niching of art is art’s last broad stroke? What if art is over? Okay, this sounds like Francis Fukuyama’s pronouncement on liberal democracy, and it’s probably not true—probably—but it seems a lot more probable than the big strokes of technology coming to an end.

Many people have noticed the sense of increasing sterility in contemporary art. It’s natural to wonder, “Hey, maybe there’s some larger picture we’re missing here. Maybe there’s a next big art thing out there that’s so big as to be invisible.” Here’s another thought: What if tech itself is the next big thing in the art world? What if tech itself is the Duchamp urinal in the twenty-first century Armory Show? Is the notion that technology = art depressing? Are you a hater to think such things? Which is better art: a performative piece whose movements are informed by real-time Los Angeles traffic patterns, or plein air watercolors of delicate song birds done on a foggy morning? Does it drive you crazy when autocorrect always flags the word “performative”?

Today, when dealers speak with a potential client about a new artist, the client almost always asks, “Is this new artist young? How young are they? And how new is the technology they’re using … has it been released or is it in beta? Is anyone else using this new technology?” The impulse behind this reflexive questioning can be one of two things: a puritanical interest in new forms and ideas—or opportunism wearing a cloak of art-world puritanism. Does this young artist have any technologies that he or she needs to unlearn? No? Great. Do they know much about the art world? No? Even greater. Do they produce actual physical things at the end of whatever it is they do? Yes? Wonderful. And finally, does this artist use something that can be related to VR or augmented reality? Yes? Okay then—Frieze, we have a perfect storm. Fifty years after McLuhan’s Understanding Media, the medium that drives the message is still the message—and sometimes it seems like the only hope for any message at all.

Implicit in this not uncommon dealer-client exchange is an unspoken assumption that new technologies allow new and hitherto unforeseen dimensions of the human condition to be made manifest. I wonder: If human beings stopped creating new technologies as of today, would the art world crater overnight? Artists would be limited to further documentation from within a fixed realm without technological novelty. With seven billion people on Earth, chances are we’d soon catalogue almost all experience available with the tools at hand. We’d enter a world of perpetual repetition with nothing new.

So who’s making all of this new technology that’s always messing with our lives? Who are these Silicon Valley inventors? And are they inventing things just to torment the world with relentless novelty? No. That would require a spoken and codified agenda which simply doesn’t exist. Are these inventors doing it to get rich? Sometimes … but as a rule, the people who make the best new stuff are usually the people with no foreground interest in money; they just want to make cool stuff—or they just want to meet their production milestones. I’ve noticed that almost nothing annoys an engineer or mathematician more than asking if they ever think about potential superpowers unleashed by the things they’re working on—whether unintended or otherwise. Only once have I received a full and honest answer to this question. A coder in an optical fiber research facility in New Jersey told me, “It can sometimes be really depressing to come to work every day knowing that all of what we do is largely to create an ever more satisfying porn experience in the $29.95-per-month price range.”

If one were to investigate the degree of interest engineers and mathematicians have in the art world qua art world, one would only find piles of Legos, Rubik’s Cubes, and Star Wars tchotchkes on office desks—three items representing binarization, proof of successful problem solving, and a timeless emotional myth with which to bond. A $50,000 productivity bonus given to a Valley engineer would, in all likelihood, be used to buy original animation cells from vintage Marvin the Martian cartoons. I once visited the Palo Alto apartment of a friend who’s an expert in 3-D fly-through experiences; in his apartment was a table, a few flat-screen monitors, several drives, and a folding chair—nothing else. I asked him when the rest of his stuff was arriving and he said, “I’ve been living here for six years.”

Is there the occasional engineer sensitized to historically and economically consolidated art? Sure. Nathan Myhrvold, Microsoft’s former CTO, had a huge, seminal Roy Lichtenstein canvas in his suburban Seattle house—but then he also has a life-size T. rex skeleton in his living room.1 Pace has a gallery in Palo Alto. Microsoft has an astonishing art collection that rivals any mature museum, and it’s also out there in the world working hard, but mostly in Microsoft facilities.2 And, oh yes, the SFMOMA has a massive new addition. You can’t call the tech world or the Silicon Valley an art wasteland. There’s a lot of work and collecting there, but it all inhabits the world in a different way. Last month I had a look at a new system that 3-D scans flat-but-textured surfaces such as paintings. The technicians who created it were trying to figure out ways to use it. Their solution was to license and scan Van Gogh paintings, 3-D print them, and then sell them for $40,000 each at a local shopping mall catering to Chinese clientele.3 The whole exercise was depressing yet enlightening. For most technicians, art = arty art with lots of brushstrokes that comes from a big old-fashioned museum. The Valley’s art tendencies default to a naive tiny chunk of Venn real estate where art and science overlap—or where they don’t overlap. The art world gets mad at the Valley for not throwing it more money, but tech is just an industry, albeit one that does very well and that happens to be geographically hyperconcentrated. I don’t see people getting angry at Big Pharma or Big Corn for not lavishly spending on art and donating to museums. If they were geographically concentrated, would we be having this same discussion? Probably not.

Is there any contempt toward the art world from Silicon Valley’s direction? Not really. Technicians have spent their lives becoming technicians, so it’s what they care about, and you could say the same about workers in many other industries. Except tech is different because technicians can make insane amounts of money and they have borderline alchemical powers to shape reality in a way that bends it to their will, whether or not the bending is cognitive, programmatic, unintentional, or subconscious. The fact that many of them become wealthy is just a bonus factor that makes the outside world curious about them: nerds—they buy crazy, nutty stuff like T. rex skeletons! It’s also a given in tech culture that human beings don’t change; only technology changes. Technology allows us to do things we never thought we were capable of doing: Apollo 11, artificial sweeteners, death camps. If the twentieth century taught us one thing, it’s that when technology changes too quickly, people tend to make really bad decisions. People who feel engulfed in chaos can be tricked into doing almost anything. So investigating the people who make the technology that triggers change isn’t necessarily an arbitrary call.

The money people—the venture capitalists—are different from techies. They’re just generic money people—albeit many have a knack for tech IPOs and have been doing it for so long that they’re as much a part of Valley ecology as frozen freeways and that Segway collecting dust in the back of the garage. But you can’t really view them differently than Wall Street money people. So, in being generic, financiers are only ancillary to decisions about the Valley’s computative agenda—which just leaves the techies to define the vision. What happens if you take the Valley’s relentless desktop triumvirate of Legos, Rubik’s Cubes, and Star Wars tchotchkes to their logical end state of binarization, problem solving, and reductive myths that occur out of time—are we approaching a world that’s being turned into a programmer’s desk? Actually, yes, and the more clearly you envision a world just like that, the closer you are to seeing the world that is actually going to happen.