Zvi Lothane, In Defense of Schreber: Soul Murder and Psychiatry (Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press, 1992, 205).

For an introductory overview of current discussions on the social brain vs. neoliberal neuromaterialism, see Charles T. Wolfe, “Brain Theory Between Utopia and Dystopia: Neuronormativity Meets the Social Brain,” in Alleys of Your Mind: Augmented Intelligence and Its Traumas, ed. Matteo Pasquinelli (Luneburg: meson press, 2015); and Victoria Pitts Taylor, “The Plastic Brain: Neoliberalism and the Neuronal Self,” Health, vol. 14, no. 6 (2010).

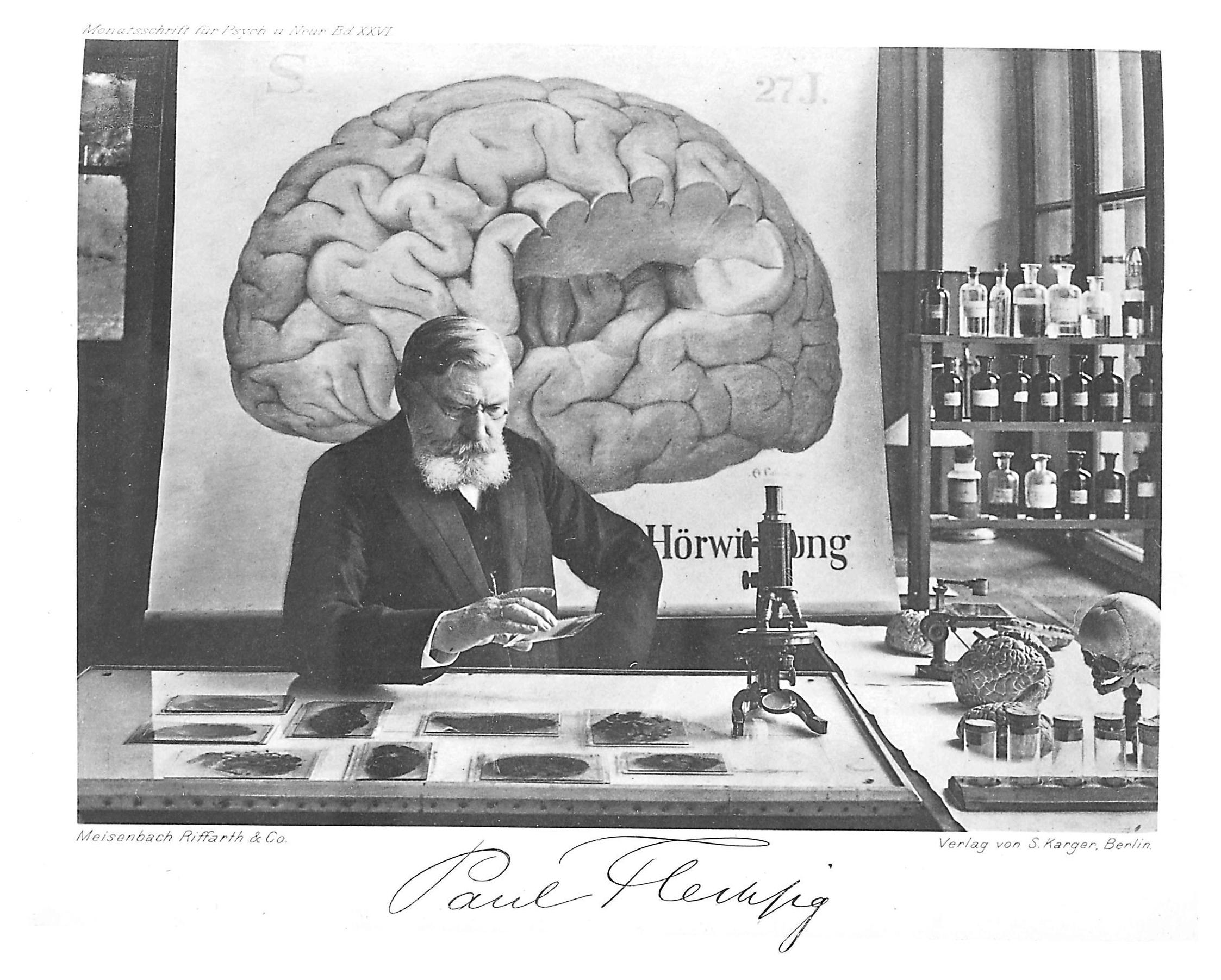

Some of Meynert’s famous students in Vienna were the Russian neuropsychiatrist Sergei Korsakoff and Sigmund Freud. One of Flechsig’s disciples, Emil Kraepelin, was one of the most influential advocates of eugenics and racial hygiene at the turn of the century.

The same publishing house released the work of Ernst Haeckel, a key figure in social Darwinism, who is discussed further below. His 1874 Anthropogenie—a book on embryology—had a significant role in Bismarck’s Kulturkampf, or “culture struggle,” of the 1870s.

For a good overview of what has been written on Schreber, see Lothane, In Defense of Schreber.

Denise Ferreira da Silva, Towards a Global Idea of Race (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).

Eric Santner, My Own Private Germany: Daniel Paul Schreber’s Secret History of Modernity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996).

Ibid., xii.

Ibid., xiii.

Ibid., 9.

Daniel Paul Schreber, “Open Letter To Professor Flechsig,” in Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (1903) (New York: New York Review Books, 2000), 8. Italics in original.

Referenced in Eric Butler, Metamorphoses of the Vampire in Literature and Film, Cultural Transformations in Europe, 1732–1933 (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2010), 133.

Friedrich Kittler, whose seminal Aufschreibesysteme 1800/1900 (first edition: Fink: Munich, 1985) takes its name from Schreber’s system of “writing-down.” In his account of Schreber’s case, Kittler sees Flechsig’s psychophysical paradigm and Schreber’s writing as two poles of the new model of arranging the social and psychic sphere. Flechsig’s work marks the moment when personhood is replaced by an information system, thus preparing the ground for the emergence of new and more effective ways for power to intrude into the body as the object of investigation. “If psychophysics can explain its effects out of existence, then experimental subjects have no choice but open warfare and thus publication. Schreber writes to Flechsig in Flechsig’s language in order to demonstrate in the latter’s own territory that Schreber’s purported hallucinations are facts effectuated by the discourse of the Other. The Memoirs stand and fight in the war of two discourse networks. They constitute a small discourse network with the single purpose of demonstrating the dark reality of another, hostile one.” Friedrich Kittler, Discourse Networks, 1800/1900, trans. Michael Metteer, with Chris Cullens(Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1990), 296–97.

Schreber’s father, Moritz Schreber, was a well-known educator and inventor of several uncanny correctional anatomical devices such as the Geradehalter, which made kids sit up straight at the table.

I am using the categories of the real, imaginary, and symbolic here quite crudely and without an absolute adherence and fidelity to how these appear in Lacanian psychoanalyses. I depart from the Lacanian triad in considering that the real is that which is beyond language and symbolization and which emerges only in moments of traumatic rupture, that the symbolic is primarily the domain of law and culture and the realm of its symbolic structures, and that theimaginary is that which relates to the illusion of totality, to fantasies of wholeness (of the image).

Franz Kafka’s “Vor dem Gesetz” (Before the Law) parable, originally published in 1915, appears in Der Prozess (1925). Available in English online →.

I borrow the term “necropolitics” from an eponymous article by Achille Mbembe (2003). Drawing on Foucault’s elaboration of the (sovereign’s) right to kill (droit de glaive), Mbembe contends that in the age of “war against terror,” the right to kill and the distribution of death become the dominant form of enacting sovereignty and power. Such necropower here connotes that the technologies of control, in the context of politics as war, actively exercise control over mortality. Mbembe’s point is that “the contemporary experiences of human destruction suggest that it is possible to develop a reading of politics, sovereignty, and the subject different from the one we inherited from the philosophical discourse of modernity.” Instead of considering “reason” as the truth of the subject we should rely on more tangible categories of life and death when discussing sovereignty in our times, in which the “state of exception and relations of enmity” have become the basis of the right to kill. Article available online →.

Santner, xiv.

Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley(New York: Penguin Classics, 2009), 13.

“We can’t go along with Maud Mannoni when she sees the first historical act of antipsychiatry in the 1902 decision granting Judge Schreber his liberty and responsibility, despite the recognized continuation of his delirious ideas. There is room for doubting that the decision would have been the same if Schreber had been schizophrenic rather than paranoiac, if he had taken himself for a black or a Jew rather than a pure Aryan, if he had not proved himself so competent in the management of his wealth, and if in his delirium he had not displayed a taste for the socius of an already fascisizing libidinal investment.” Ibid., 364.

Santner, 71.

Christian Grothoff and J. M. Porup, “The NSA’s SKYNET program may be killing thousands of innocent people,” Ars Technica UK, February 2, 2016 →

The relation between brain, mind and the machine occurred persistently in the Macy conferences, as well as the problem of psychoanalysis and unconscious. The contestation between the position of “hard sciences” and “mentalist” perspectives of psychoanalysis and experimental psychology appeared repeatedly in the meetings. For example in the 7th conference (1950) L. Kubie’s lecture on neurosis and its relation to language and symbols triggered a debate in which Pitts and Bateson attacked psychoanalysis of not being a science since it was not based on any coherent theory or objectivity. Psychiatry in general was seen as unscientific. In the following conference, an influential collaborator of Norbert Wiener, the Mexican physician Arturo Rosenblueth suggested that neural events either happens or it does not, basically dismissing the category of the ‘unconscious’ altogether as nonsense and positing that natural sciences can handle all the problems conventionally addressed by psychiatry. In addition, Walter Pitts proclaimed that psychiatrists should be able to demonstrate that their methods are 'scientific'. And while Pitts (who himself gave in to mental illness) and Warren McCulloch vigorously denied unconscious, Norbert Wiener believed that the discipline of psychoanalysis could productively be rethought in terms of communication and feedback. Lydia H. Liu for example, contends that psychoanalysis continued to “haunt” the cyberneticians (Liu: Freudian Robot. Digital Media and the Future of Unconscious, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2010). For a more general overview of Macy Conferences (interdisciplinary gatherings of academics and researchers held in New York Between 1946 and 1953, sponsored by the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation) see for example: Steve Heims: The Cybernetics Group, MIT Press, 1991 and Jean-Pierre Dupuy: The Mechanisation of Mind, MIT Press, 2009. For the transcripts of the 10 conferences see the recent Cybernetics: The Macy Conferences 1946-1953. The Complete Transactions. Ed. by Claus Pias, Zuerich: Diaphanes, 2015.

Laurence Rickels, I Think I Am: Philip K. Dick (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 68.

Reza Negarestani, “The Labor of the Inhuman,” in #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader, ed. Robin Mackay (London: Urbanomic, 425–466).

See the essay “The Paradigm of Incomputability” by Antonia Majaca and Luciana Parisi in an upcoming issue of the e-flux journal.

This essay was originally written for the volume Nervöse Systeme, edited by Anselm Franke, Stephanie Hankey, and Marek Tuszynski, for HKW - Haus der Kulturen der Welt and published by Matthes & Seitz, Berlin in January 2017.