From a Chemist’s Shelf to a Communist Museum on Mars

If you have “avant-garde” and “museology” or “museum exhibitions” in one sentence, especially if that sentence is in English, the first name that comes to mind is El Lissitzy and his collaboration with Alexander Dorner in Hannover.

Everyone who has an interest in experiments with display design has seen images of the Abstract Cabinet installed at Landesmuseum in late 1928. This masterpiece marks the limit of known ambitions for the transformation of the museum in the time associated with the young Soviet state or even the historical avant-garde. But most interpretations of the Abstract Cabinet reduce its meaning to formal innovations distinctive for Western modernism. The new concept of the museum that resulted from the combination of new social relationships and a political agenda remains unconsidered.

I’d like to risk going beyond this limitation to describe the trajectory and logic of the transformation of the concept of the museum and art in general from the late nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century in Russia and the Soviet Union.

Let’s use the proletarian revolution in Russia as a point of departure for our discussion of avant-garde museology. Not only did this event determine a majority of interpretations of art and the role of institutions charged with preserving art after the fact, it also served as a point of attraction for the goal of establishing social equality even before it took place. Beginning from the revolution will make it easier to describe the radicalized conceptions of the museum that emerged at the time, and the hierarchy of these conceptions. At its foundantion lies the historical avant-garde’s destructive impulse towards any attempt to preserve the past. Kazemir Malevich expounded this idea, writing in 1919: “Contemporary life has invented crematoria for the dead, but each dead man is more alive than a weakly painted portrait. In burning a corpse we obtain one gram of powder: accordingly, thousands of graveyards could be accommodated on one chemist’s shelf.”

Others expressed similar opinions. The majority of artists associated with the historical avant-garde were sharply critical of the museum as an institution. Those who did not clamor for the incineration of the past in the crematoria of the present nevertheless spoke of the need to take control of the institution and reorganize it with a view to creating conditions more favorable to the new art. If the museum were to survive, it had to become highly mobile; it had to keep pace with the transformations of reality as it sped towards socialism. Radical theorists of futurism, for example Osip Brik, insisted that the museum should be transformed into a scholarly institute. Avant-garde theoretician Nikolai Punin complained to colleagues about the museum-as-repository: “One cannot breed contemporary European art museums out of the ‘kunstkammer’ and the ‘repos’ any more than one can hatch the contemporary state directly from the feudal order. Museums were once “repos,” but for a long time they have developed a different character—an auxiliary scientific character.”

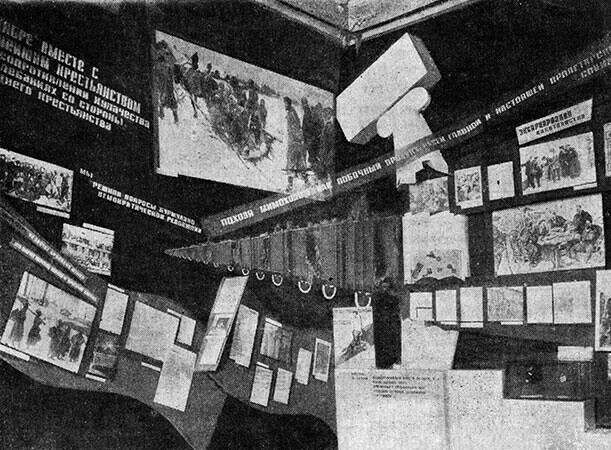

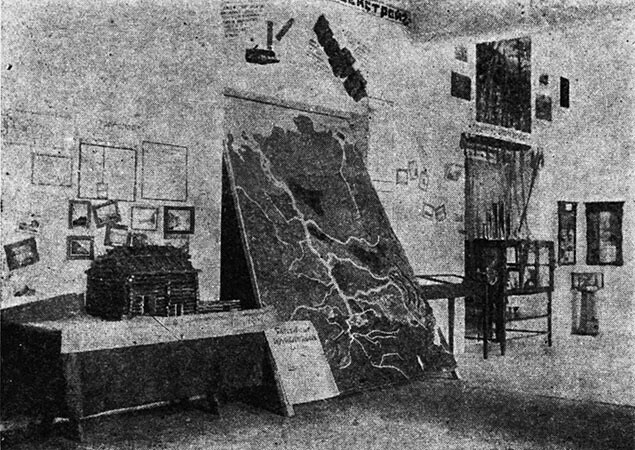

Exhibition on ”The History of the Civil War” at Leningrad Museum of Revolution, 1930.

Exhibition on ”The History of the Civil War” at Leningrad Museum of Revolution, 1930.

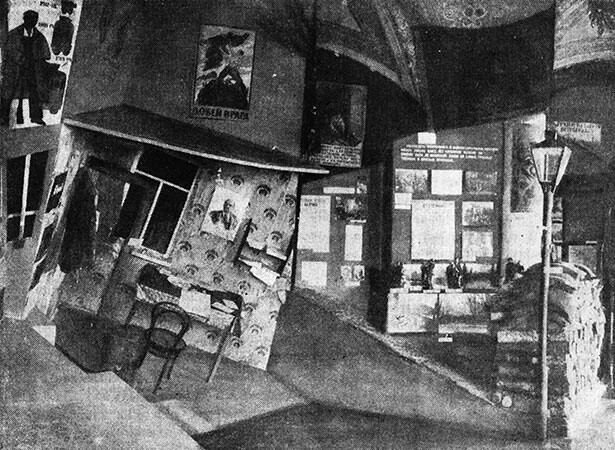

Exhibition view of the Museum-Newspaper at the Krasnoyarsk Museum, Krasnoyarsk, c. 1930s.

Exhibition on ”The History of the Civil War” at Leningrad Museum of Revolution, 1930.

Malevich might have been closer to anarchism in terms of his political preferences, but at its core his and similar thinking was inspired by the Marxist interpretation of artistic creation under conditions of capitalist production and its potential transformation after the revolution, when the emphasis of the artistic activity should gradually shift from the museum towards everyday life and production. Because without social equality art is mainly a ghetto for imaginary solutions to the traumas of exploitation and the ruling class’s violence against the oppressed. And in this situation, the museum fixes this order of things institutionally, under the name of art history. Consequently, the museum could be seen as an enemy of the revolution, doomed to be destroyed. But if society overcomes the social contradictions associated with class struggle and inequality, then art as a bourgeois ghetto will melt into liberated reality. The artist, as a special professional occupation, will gradually give way to the engineer—be it an engineer of industrial machines or social interactions.

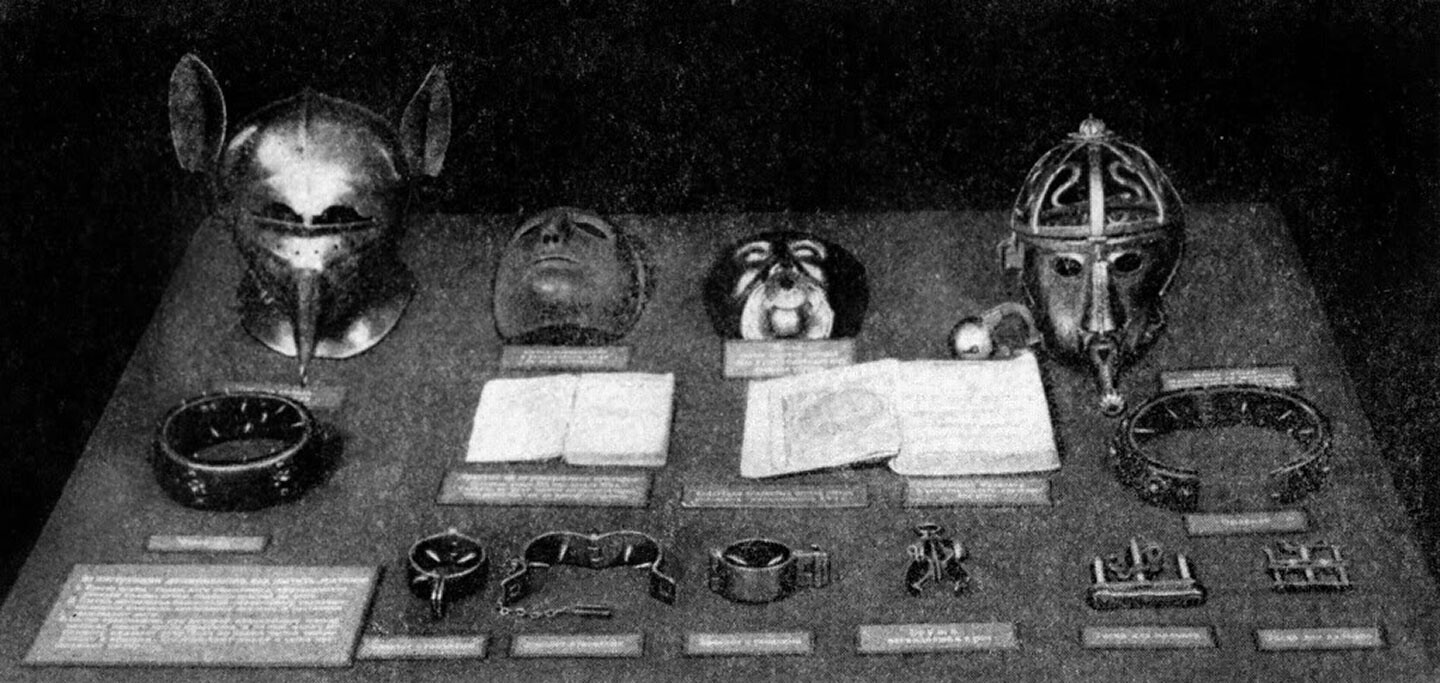

A display case exhibits the inquisition’s instruments of torture in the exhibition of the Museum of Atheism, Leningrad.

The position of the “proletkult”—short for “proletarian culture”—came close to the radical position of a Malevich. Proletkult was a broad movement of unprofessional poets, writers, theatrical activists, film directors, and artists who tried to build a new proletarian culture through the negation of the art of previous epochs, in a practical attempt to destroy the museum as a castle of enemy-class culture. The intellectual leader of proletkult was Alexander Bogdanov, who started as a professional revolutionary and close collaborator of Lenin but was later forced from political activity and started working as a scholar and a cultural organizer. Thanks to Bogdanov, proletkult was influenced by the ideas of Russian cosmism, which resulted in a series of narratives of Communist space exploration written by self-taught poets.

Almost a decade before the revolution, Bogdanov depicted a postrevolutionary Marxist museum in his science-fiction novel Red Star from 1908. “I imagined there would be no museums in a developed communist society,” exclaims Bogdanov’s astonished protagonist upon finding that the instituion has survived on Mars, home to a highly advanced Communist civilization. The museum has indeed survived, but its function has been modified. It is no longer a bourgeois ghetto, a repository for all the delusional hopes for the resolution of social contradictions. Instead, the liberating force of proletarian revolution has dissolved class divisions as such, and art, once an autonomous professional sphere, has been integrated into the everyday life and work of humanity. “The museum showcases distinct specimens of art conducive to the upbringing of new generations,” replies Enno, a Martian Communist, to Bogdanov’s protagonist. The conversation continues:

“I must say I never even imagined that you might have special museums for works of art,” I said to Enno on our way to the museum. “I thought that sculpture and picture galleries were peculiar to capitalism, with its ostentatious luxury and crass ambition to hoard treasures. I assumed that in a socialist order art would be found disseminated throughout society so as to enrich life everywhere.”

“Quite correct,” replied Enno. “Most of our works of art are intended for the public buildings in which we decide matters of common interest, study and do research, and spend our leisure time. We adorn our factories and plants much less often. Powerful machines and their precise movements are aesthetically pleasing to us in and of themselves, and there are very few works of art which would fully harmonize with them without somehow weakening or dissipating their impact. Least decorated of all are our homes, in which most of us spend very little time. As for our art museums, the [art museums] are scientific research institutes, schools at which we study the development of art or, more precisely, the development of mankind through artistic activity.”1

Before proletkult’s vision of the communist colonization of Mars, exhibition-making led to “avalanche exhibitions,” i.e., worker-organized and continually augmented exhibitions at factories. This vision of the Communist museum was later repeated by avant-garde artists and activists who could not support the full destruction of the institution outlined by Malevich. Instead of smashing it, the revolutionary must appropriate the museum for the purposes of propaganda—for “good art,” which was avant-garde art and which served to educate the proletarian masses. In essence, the idea was to create a museum that could answer to the professional demands of pioneering artists—to create, that is, a museum of avant-gardism. The demands, however, focused principally on access to exhibition facilities and changes in the purchasing policy that would benefit innovative art. There was no talk of transforming the very role of the museum beyond a more active approach to exhibitions and a greater emphasis on the museum’s undoubtedly important educational function. As Nikolai Punin wrote: “The museum collections are archives to be consulted freely by anyone who wishes to do so. Let the paintings be hung and rehung without any interruption. Ideally, the museum must be made entirely of moving parts. Any tendency towards the stasis of the church icon must be eradicated.”

A professional version of the avant-garde museum opened in Moscow in 1919 in the form of the Museum of Painting Culture. The new institution was run by artists and mainly attended by a professional audience.

In his polemical remarks on the “museum bureau,” the avant-garde artist Aleksandr Rodchenko proposed fundamental changes to exhibition strategies espoused by the old-guard museum:

First of all, the gallery and the wall are construed as equipment for displaying the artwork. Under such formulation there can be no question of economy of wall space. Wall-to-wall coverage is categorically rejected. The wall is no longer construed as an autonomous entity, and the artwork does not adapt itself to the wall. Instead the artwork becomes an active participant.

***

Once the Bolsheviks were established as a real political government, they could not support the avant-gardists’ initial demand for the destruction of museums either. Years of revolution and civil war had left Russia a very weak and exhausted country. Art not only had cultural value, but a material value as well, which limited revolutionary violence under these particular historical circumstances. Simple destruction was not a wise decision from a practical point of view. At the same time, the avant-garde appropriation of the museum as a tool for propaganda art did not work out as planned either. One possible solution to this dilemma was proposed by Leon Trotsky in his debates with the proletkult movement. His approach was somewhere in between the early Bolshevik support of the left-wing avant-garde and the later Bolshevik support of more traditional socialist realism.

Trotsky claimed that it was necessary to appropriate and preserve the cultural treasures of previous epochs, because a new proletarian culture couldn’t rise without sufficient educational background and access to museums. According to Trotsky, the fetishism of unskilled art production expressed by proletkult was not enough for building a new culture and a new human freedom. The new artist-workers had to reclaim the cultural treasures that had been stolen from them as surplus value. But the crucial question was how to use these treasures without arousing sympathy for antagonistic classes.

“The Experimental Complex Marxist Exhibition,” proposed by Alexey Fedorov-Davydov and mounted at the State Tretyakov Gallery in 1931, was supposed to resolve this dilemma. The idea was to contextualize art production according to different class positions, as expressed by different works of art. Fedorov-Davydov constructed complexes of different styles that characterized different class positions. Each complex consisted of a number of different artistic mediums, including furniture.

The exhibition was built as a series of rooms with the typical interiors of collectors from different class positions. It also had supplementary material about the economic and political specificity of each room. Thus, the thinking went, proletarians could understand the connection between art and its social background. “The Experimental Complex Marxist Exhibition” resonated with Victor Shklovsky’s idea of defamiliarization or estrangement, later adopted as the “alienation effect” in the theater of Bertolt Brecht. It deconstructed the illusion of the museum as a temple of art, but left open the possibility of learning from the masterpieces of previous epochs.

In addition to works already recognized as art by capitalist museums, Fedorov-Davydov included works by peasants and proletarians, along with political slogans and street advertisements. And for visitors who wanted a more advanced or professional view of the development of artistic forms throughout history, Fedorov-Davydov included special cabinets that repeated the logic of the avant-garde Museum of Painting Culture.

Exhibition view from “Labor and Art of Women of the Soviet East” in the Museum of Oriental Cultures, c. 1930s.

An experimental Marxist exhibition at the Russian Museum, Leningrad, 1920s. On the wall a quote from Lenin reads “The philosophy of the anarchists is bourgeois philosophy turned inside out.”

Exhibition view from “Labor and Art of Women of the Soviet East” in the Museum of Oriental Cultures, c. 1930s.

For a short period of time between Lenin’s death and Stalin’s deployment of the Socialist Realist apparatus, the reappropriation of bourgeois culture for educational purposes became the dominant model in Soviet museums. Dialectical materialism was named the principal method of museum activity. This meant that in contrast to the bourgeois museum of the past, its Soviet counterpart must treat natural history, social history, and the cultural sphere not as alienated and antagonistic to man, but as products of his conscious effort. The “kunstkammer”—the vulgar materialistic or idealistic museum—would be replaced by the museum as an integral aspect of the artistic transformation of life. Passivity, neutrality, and the positivist or metaphysical stance of the museum with respect to the phenomena within its purview would become a thing of the past. Political engagement, partisanship, direct participation in industrial processes and in the ongoing class struggle, critique of ideological superstitions, critique of fetishism—these were the new guiding principles and slogans of Soviet museology of the late 1920s early ’30s.

The first Museological Congress was an important milestone in the drive towards the new museology. However, there was no tried and true procedure whereby the museum was expected to put the principles of dialectic materialism into practice. This, in turn, opened the doors for experimental ideas.

An important innovation of Soviet museology was the museums of the revolution, the very idea of which seems contradictory in and of itself. Indeed, the revolution is an event that in its scale transcends any traditional methods of representation or archiving. And yet the works in the museums of the revolution became one of the most important artistic discoveries of twentieth-century museology.

And if the museum of the avant-garde was a museum of the ongoing rupture in the history of art, effectively the prototype of the modern or contemporary art museum, then the museum of the revolution served the same function with respect to social history. It often pushed the boundaries of traditional media even further than the most radical artists of the time. The very structure of the exhibition in a revolutionary museum is a collage of varying types of artistic media and auxiliary non-artistic information, facilitating their analysis. In the Soviet museum the critique of spectacle through alienation was meant to awaken in the viewer a conscious stance, grounded in the understanding of historical processes. And this was the principal distinction between the Soviet and the fascist museum, which used similar means to achieve opposite ends.

One of the outcomes of the dialectical approach to the museum was the apparent need to bring the institution into everyday life, i.e., for the museum to transcend its own boundaries. In this respect Soviet museologists were very much in accord with the avant-garde artists. At the same time, their engagement with industrial production and agriculture had a more systemic character and was, moreover, materially supported by the state. In the pages of the journal Soviet Museum we find numerous reviews of so-called “itinerant exhibitions,” i.e., mobile exhibitions that traveled to locations that lay far beyond the reaches of traditional museums. Museum agit-trains and mobile museums housed inside vehicles were organized as part of the campaign aimed at the successful completion of socialist construction.

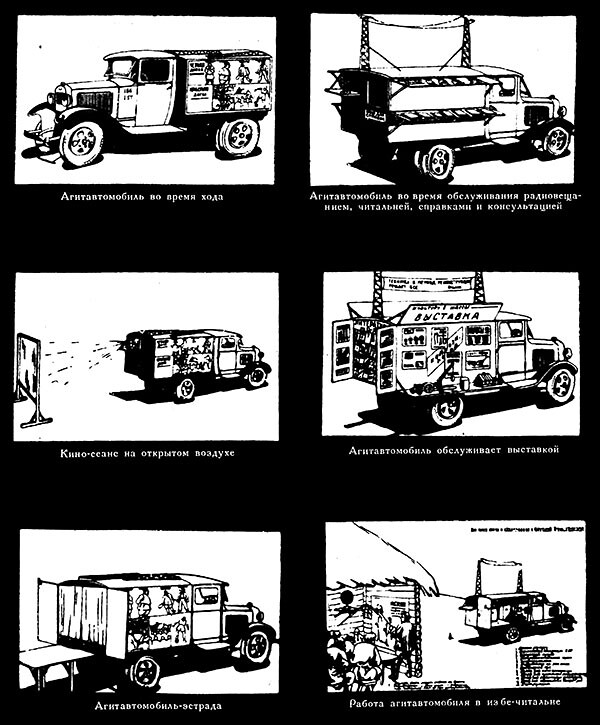

“The agitprop-truck on the go; The agitproptruck functioning as a radio, library, and an information point; The agitprop-truck as an outdoor cinema; An exhibition at the agitproptruck; The agitprop-truck is transformed into a stage; The work of the agitprop-truck in conjunction with the local reading hut,” from M. S. Ilkovsky’s text “Bringing the Agitprop-Truck to the Service of Cultural Construction,” Soviet Museum no. 3, (1932).

Another example of museological innovation is the industrial museum project of D. E. Arkin. The project largely echoed the ideas of the industrial avant-garde, developed by Boris Arvatov, but implemented them at the institutional rather than the individual level. The industrial museum was a laboratory-museum, tasked with preserving and developing creative prototypes for subsequent implementation into production. This concerned first of all handcrafts and design-based industries such as textiles, ceramics, etc.

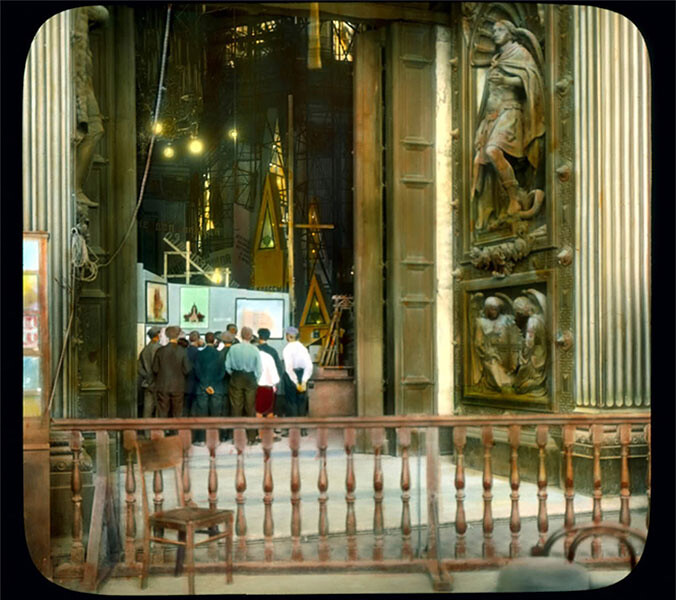

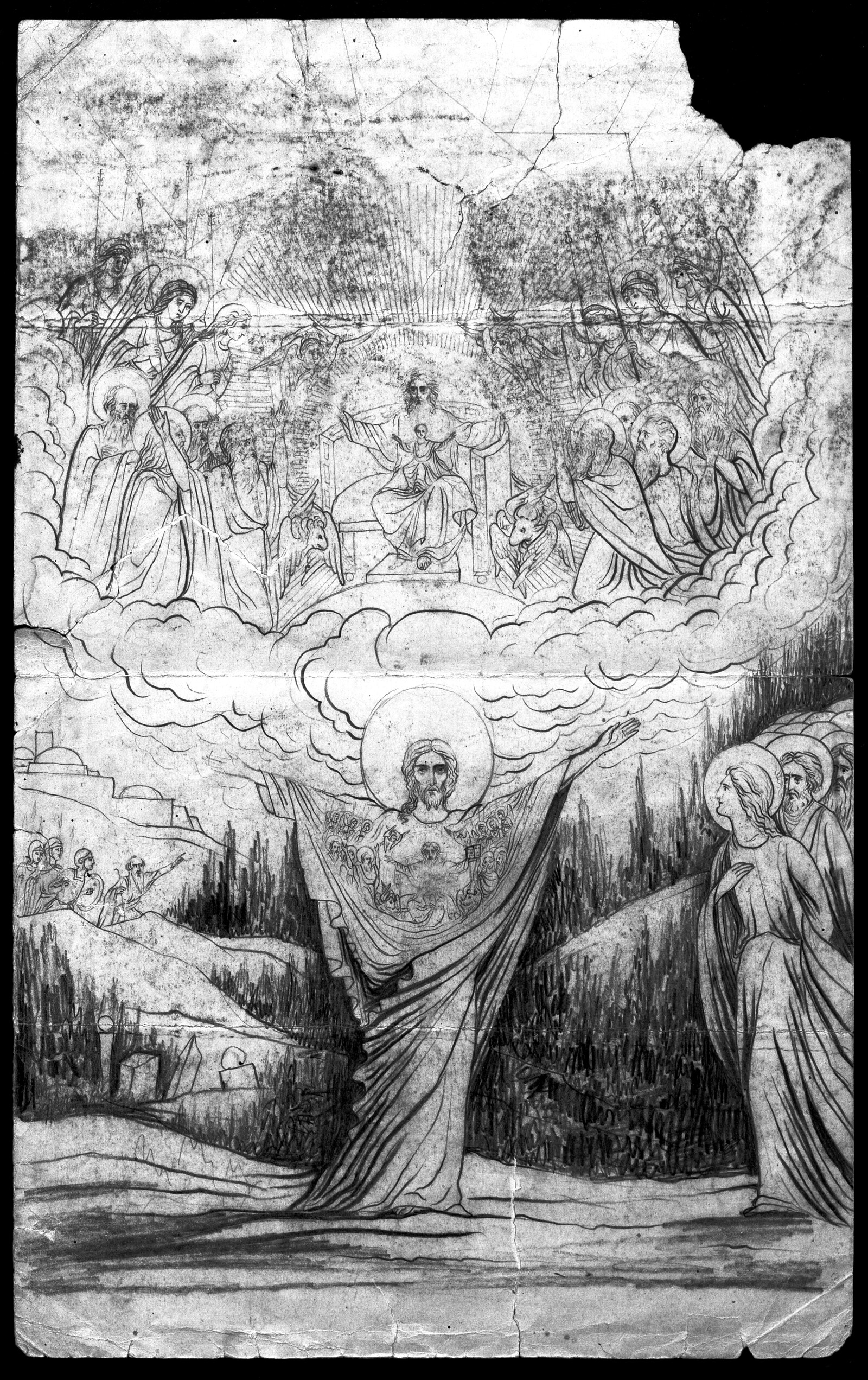

Right and left images: Exhibition view at Museum of Atheism, Leningrad, the former St. Isaac Cathedral, date unknown.

Right and left images: Exhibition view at Museum of Atheism, Leningrad, the former St. Isaac Cathedral, date unknown.

A peculiar variation on the dialectical-materialist museum was the atheist museum. The original materialist critique of religion as a refuge for irreconcilable social contradictions belongs to Feuerbach. In the visual arts, however, one had to wait for the iconoclastic impulse of the historical avant-garde to mount an artistic critique of religion as a kind of camouflage for exploitation and social inequality. The Soviet years saw the rise of the Union of Militant Atheists, numbering several million members at one point. Many of the major church compounds were expropriated for the use of various kinds of antireligious institutions. Modest museums of atheism were organized in schools and workplaces. The opposing tendencies—on the one hand, calling for the preservation and study of religious art, and on the other, for the total rejection of an alien and dangerous ideological delusion—determined the specific character of antireligious museums and, at the same time, served as the driving force of their development in the Soviet Union.

***

Returning to the proletarian revolution and the dilemma of art after it, Boris Arvatov, theorist of productivism, had suggested that even when, in the advanced Communist future, the social contradictions are resolved, there will still be a place for traditional media like painting and sculpture. This is because even advanced Communists will be left with physical bodies subject to various traumas and affects. The strongest and most significant of these is death, on the one hand, and love or sexual reproduction, understood as an attempt to overwhelm death, on the other. In this way, Arvatov was theorizing about the potential boundaries of avant-garde interpretation of postrevolutionary art, drawing them precisely at the point where the museum proposed by Russian Cosmists was to begin. This museum starts with a victory over death, resurrection, and the overcoming of the need for traditional sexual relationships.

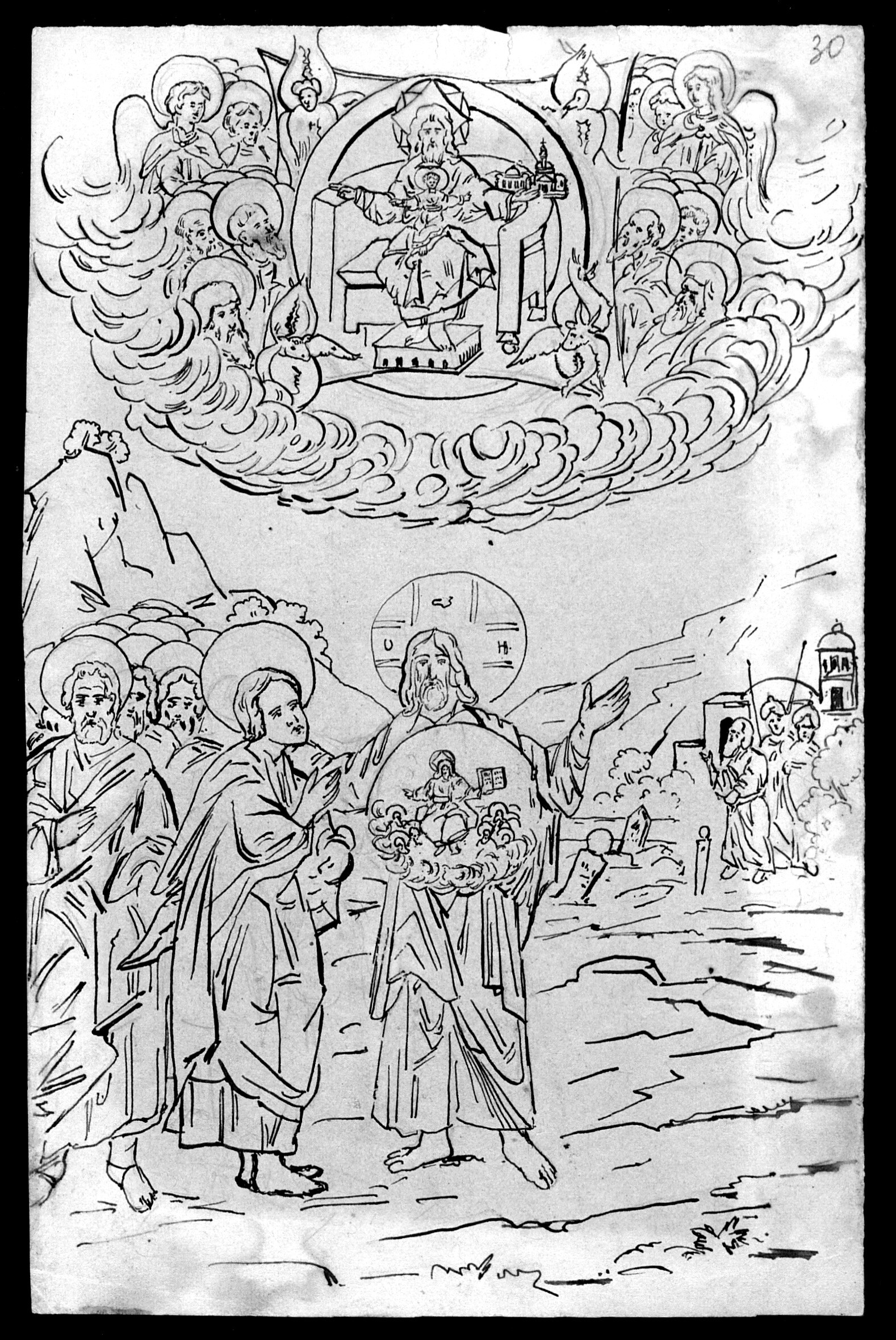

All images: Lev Soloviev’s sketches for the icon High Priestly Prayer (1898).

All images: Lev Soloviev’s sketches for the icon High Priestly Prayer (1898).

The idea of the museum as a staging ground for transcending the limitations—both social and physical—imposed upon mankind can be traced back to the works of Nikolai Fedorov, one of the most prominent exponents of religious philosophy, originator of the philosophy of the “common task,” and founding father of the Russian Cosmist movement, which in large part inspired the Soviet space program.

The idea of space colonization was a natural consequence of Fedorov’s conception of man as a transformational force in the Universe, a kind of universal artist whose role is to impose the necessity of the regulations of nature and the cosmos. One of the key aspects of this process was the resurrection of the dead and the subsequent resettlement of newly resurrected generations on planets in outer space.

Space exploration, however, was not a principal tenet of Fedorov’s teaching. His common task was the need to assume direct control over the mechanisms of evolution in order to defeat death. At the same time, mere immortality would not suffice: the generation destined to triumph over death would still stand on the graves of all those who gave their lives in the service of this ideal. Thus, the blessed brotherhood of the Sons would be forever indebted to the Fathers. The ethical radicalism of the idea of indebtedness became the driving force behind Fedorov’s futuristic constructs. The creative transformation of the universe and its planets into spaceships, the regulation of natural phenomena on the Earth and beyond, the transcendence of humanity—these are some of the striking results of the idea that mankind must assume an active position with respect to the debt it owes its dead ancestors. And one of the central places in this agenda is occupied by the museum, understood in the broadest sense of the word as an institution that can subsume all of man’s activities in the service of the common task.

Needless to say, the museum as it existed towards the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries could not accommodate such an ambitious project. Fedorov mounts a strident critique of traditional museum practices. He notes that the museum had often been used to enshrine mankind’s poverty, strife, and misconceptions concerning its destiny. The museum of the future, on the other hand, must be construed as a place of reconciliation, an institution that, like the church, will register every new life and every new death. But the church, which proffers an important—but so far illusory—intuition of immortality must extend it to other institutions, and thus be supplemented by the museum, regarded as a research facility for the preservation and resurrection of every individual in his physical and mental totality. Hence the need to combine the museum with a scientific laboratory, library, and church-school. As Fedorov wrote:

Aesthetics is the science of recreating all those rational beings who have been on this little Earth (this drop of water which reflected in itself the whole Universe, and reflected the whole Universe in itself) for their vivification (and control) of all the huge heavenly worlds that have no rational beings. In this re-creation is the beginning of eternal bliss.2

In the second half of the 1890s, Fedorov traveled regularly to Voronezh to visit with his friend and former pupil Nikolai Peterson. There he became acquainted with the founder of the Voronezh Regional Museum, S. E. Zverev, a priest and regional ethnographer, and was subsequently instrumental in organizing several of the Museum’s exhibitions:

Since 1896, at Fedorov’s initiative, the Museum has mounted a number of theme-based exhibitions devoted to the most significant events of the year, a practice that later became a tradition. Between 1896 and 1899 we organized six such exhibitions: on the subject of the Coronation (May 1896) and on the rule of Catherine (November 1896); an exhibition of engravings bearing religious themes (May 1897); an exhibition devoted to St. Mitrophan of Voronezh (Nov.–Dec. 1897); an exhibition commemorating one hundred years of the printing trade in Voronezh (May 1898); and an exhibition titled The Nativity of Jesus Christ and Conciliation (Dec. 1898–Jan. 1899).

Fedorov was directly involved in each case: he chose the theme and participated in the selection of materials, some of which were either brought to Voronezh by him personally or delivered from Moscow at his request. He also wrote the introductory articles for three of the exhibitions: on Catherine the Great, on the printing trade and on the Nativity.3

Voronezh also became the site of the first incarnation of the Resurrecting Museum, created by the local artist and disciple of Fedorov, Lev Solovyev. A widower, Solovyev was determined to resurrect the memory of his lost wife by turning his home and garden into a prototype of the museum of the future. To this end he opened a free painting school and created several studies for murals that would decorate the walls of the Resurrecting Museum. Fedorov highly valued the project, devoting several articles to it and including his literary description of the museum of the future in an article titled “The Voronezh Museum in 1998”4

The second attempt to realize Fedorov’s Resurrecting Museum project was made in the early 1920s by the avant-garde artist Vasily Chekrygin. Chekrygin was twenty-three when he first encountered Fedorov’s ideas. By that time he had already served on the front lines of World War I (albeit not by choice), had befriended Mayakovksy, and was instrumental in founding the artistic movement “Makovets.” The philosophical doctrine of the common task had so impressed the young artist that he devoted the final years of his life to making sketches for the monumental fresco that would grace the walls of the Resurrecting Museum, and to a prose poem of the same name. The poem was completed, but Chekrygin’s artistic vision was never realized. The correspondence between Chekrygin and Nikolai Punin that has come down to us contains a discussion of the idea of synthetic art and the Resurrecting Museum project. Unfortunately, these two leaders of the cultural revolution were unable to reconcile their ideas: in 1922 Chekrygin was killed in a train accident at the age of twenty-five. His Resurrecting Museum remained confined to paper.

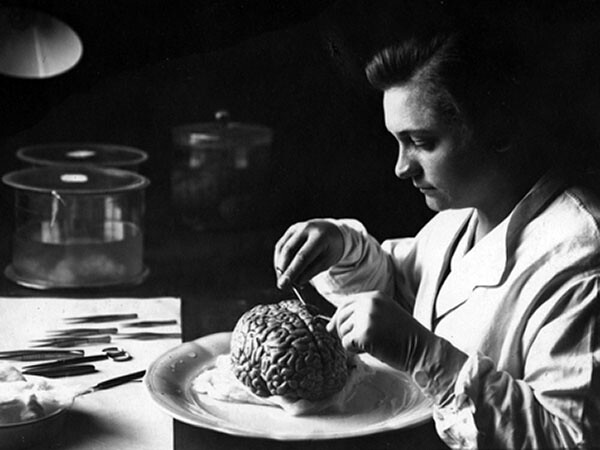

Another project that may be considered alongside Fedorov’s ideas on the museum is the Pantheon of the USSR. The project belongs to the renowned Soviet neuropathologist and psychiatrist Vladimir Bekhterev, one of the pioneers of reflexology. In the final years of his life Bekhterev became convinced of the need to create an institution that would study the brains of leading Soviet citizens with the aim of finding connections between the physiological features of the cerebral cortex and the individual’s mental abilities. Bekhterev called for a special legislative act requiring the brains of all prominent Soviet citizens to be extracted at their death and delivered by a special commission to the institution in question. In addition to its research activities, the Pantheon of USSR would also house an exhibition hall showcasing actual brain specimens, plaster casts and molds, as well as products of the individuals’ creative activities, and biographical information and psychological profiles based on data from close relatives and associates of the deceased.

An Soviet-era image of a scientist working at the Moscow Brain Institute, date unknown.

This image and images to the right: A different views of a derelict branch of the Moscow Brain Institute, c. 2000-10.

An Soviet-era image of a scientist working at the Moscow Brain Institute, date unknown.

Bekhterev was a prominent figure, occupying the influential position of director of the Leningrad Institute for Reflexology, and his proposals received considerable attention at the highest level. Bekhterev’s remarks calling for the creation of the Pantheon were printed in Izvestiya, one of the most widely read papers of the time. The launch of the project was, moreover, to mark the ten-year anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. But before his plans could be realized, Bekhterev died unexpectedly, under circumstances that remain mysterious. A commission convened for the occasion resolved to cede the project’s mission to the already existing Institute for the Study of the Brain, which at that point already possessed Lenin’s brain and would soon receive Bekhterev’s own. This marks the beginning of the history of the successor project to the Pantheon, which continues to this day. We know that the collection of the Institute for the Study of the Brain was significantly enlarged in the 1920s and ’30s, receiving, among others, the brains of the following citizens: the poet Andrei Bely; Alexander Bogdanov; psychologist and Marxist philosopher Lev Vygotsky; writer Maksim Gorky; fellow revolutionary and Lenin’s wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya; prominent party and cultural leader Anatoly Lunacharsky; poet Vladimir Mayakovsky; physiologist Ivan Pavlov; leader of the international Communist movement Clara Zetkin; and one of the founding fathers of the Soviet space program, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

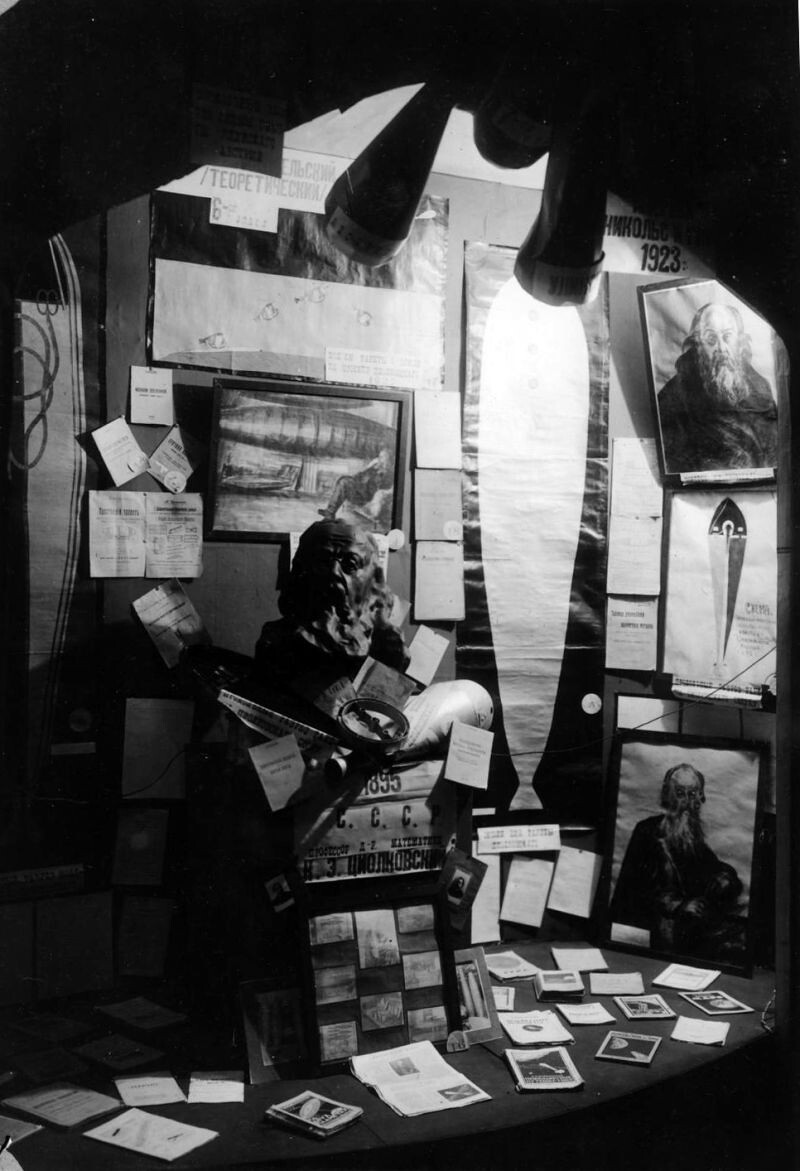

All images: View of The First World Exhibition of Interplanetary Spacecrafts and Mechanisms, 1927 Moscow.

All images: View of The First World Exhibition of Interplanetary Spacecrafts and Mechanisms, 1927 Moscow.

Although Fedorov’s philosophical legacy was never published in systematic form during his lifetime, the ideas of Cosmism lived on in the works of his pupils and disciples. The foundations of the Soviet space program laid by Tsiolkovsky, the writings of the proletkult poets under Bogdanov’s guidance, and the general awareness of momentous social changes all contributed to making the theme of space exploration one of the major components of Soviet cultural production. Accordingly, without any overt reference to the common task or the role it ascribed to the museum, Soviet museums began organizing observation decks for astronomical observation and measurement. At the same time, the idea of the rational exploitation of natural resources and agriculture became an indelible component of exhibitions-laboratories that traveled to distant villages spreading scientific knowledge.

Today, of course, Fedorov’s ideas sound rather weird. Total resurrection, a museum that collects as much information about living humans as possible … But if we replace “museum” with “archive” or even “Big Data center,” we understand better what Fedorov was striving for. In fact, big corporations like Google, Facebook or systems of governmental surveillance can be regarded as a belated realization of Fedorov’s impulse to preserve traces of life. The only difference lies in the purpose of such activity. Instead of obtaining control or money, for Fedorov this information was to be used as a tool for social development, educational planning, and extending our lives.

Avant-Garde Museology, ed. Arseny Zhilyaev (New York: e-flux classics, 2015), 256.

Avant-Garde Museology, ed. Arseny Zhilyaev (New York: e-flux classics, 2015), 146.

Nikolai Fedorov, Sobraniya sochineniy (Collected Works) vol. 3 (Moscow: Tradition, 1995–2005), 235.

Don no. 64, June 14, 1898.

A version of this essay was originally presented at the Walker Art Center as part of Avant Museology, a two-day symposium copresented by the Walker Art Center, e-flux, and the University of Minnesota Press. Video documentation of the original lecture at the Walker can be found here.