Refugee Heritage conversations: response #4–6

On protection, narrative, and humanitarianism

Ismae’l Sheikh Hassan, “Illusions and Wizardry”

The Palestinian camp embodied the idea of the Palestinian city of exile, where Palestinians from Palestine’s occupied cities and demolished villages, no matter rich or poor, created together a new form of Palestinian urbanity. In that context, Palestinian camps are the icons of Palestine’s modern architecture and urbanism. Liberation and emancipation have been central themes of this modern project and have inspired a new, rich tradition of Palestinian literature, poetry, music and various artistic productions.

But Palestinian camps are not only about Palestine and the Palestinians. On one hand the history and story of Palestinian camps and refugees speak to all cultures facing insurmountable odds and the challenge of perseverance. On the other, the spaces of Palestinian camps often play very strategic roles in providing sites of refuge and residence to a variety of non-Palestinian communities, including migrants and other Arab, Asian, and African refugees. Palestinian camps offer a critique of contemporary politics, current political systems and the increased securitization of the modern city.

Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, “The Coming of Heritage: Shimelba in Time”

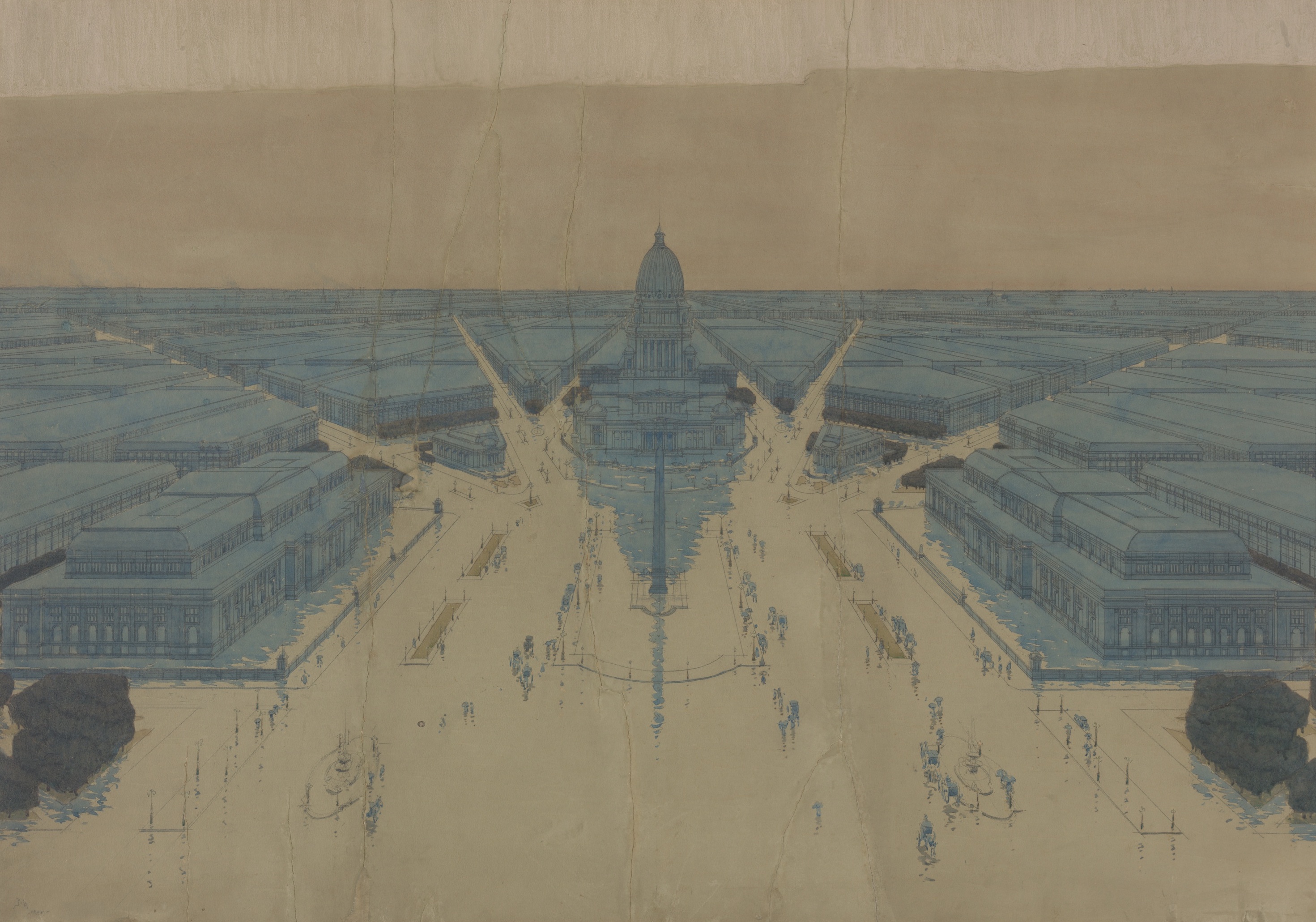

In 2011, the architectural heritage of Shimelba camp could be experienced through an arresting suture of two built fabrics. The first was composed of urbane thoroughfares, street cafes, and cinema houses populated by the highly literate Tigrinya majority—men who fled Asmara to avoid conscription into the war with Ethiopia. These abutted the second: villages of clay granaries, itasena (grass houses), and farms belonging the agrarian Kunama minority who cultivated and greened land that they saw as belonging to them, as part of a contiguous home territory in Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan. These two cultural and architectural realizations appeared distinctly in a site too remote for other forms of development, only to be abandoned after a few years, ostensibly because of political promise elsewhere. Such rupture between the urban and the bucolic has been exploited in a century of garden city movements around the world, and is a legible element in modern architectural heritage—but for an environment putatively constructed under the terms of political foreclosure?

Sari Hanafi, “Anti-Humanitarianism”

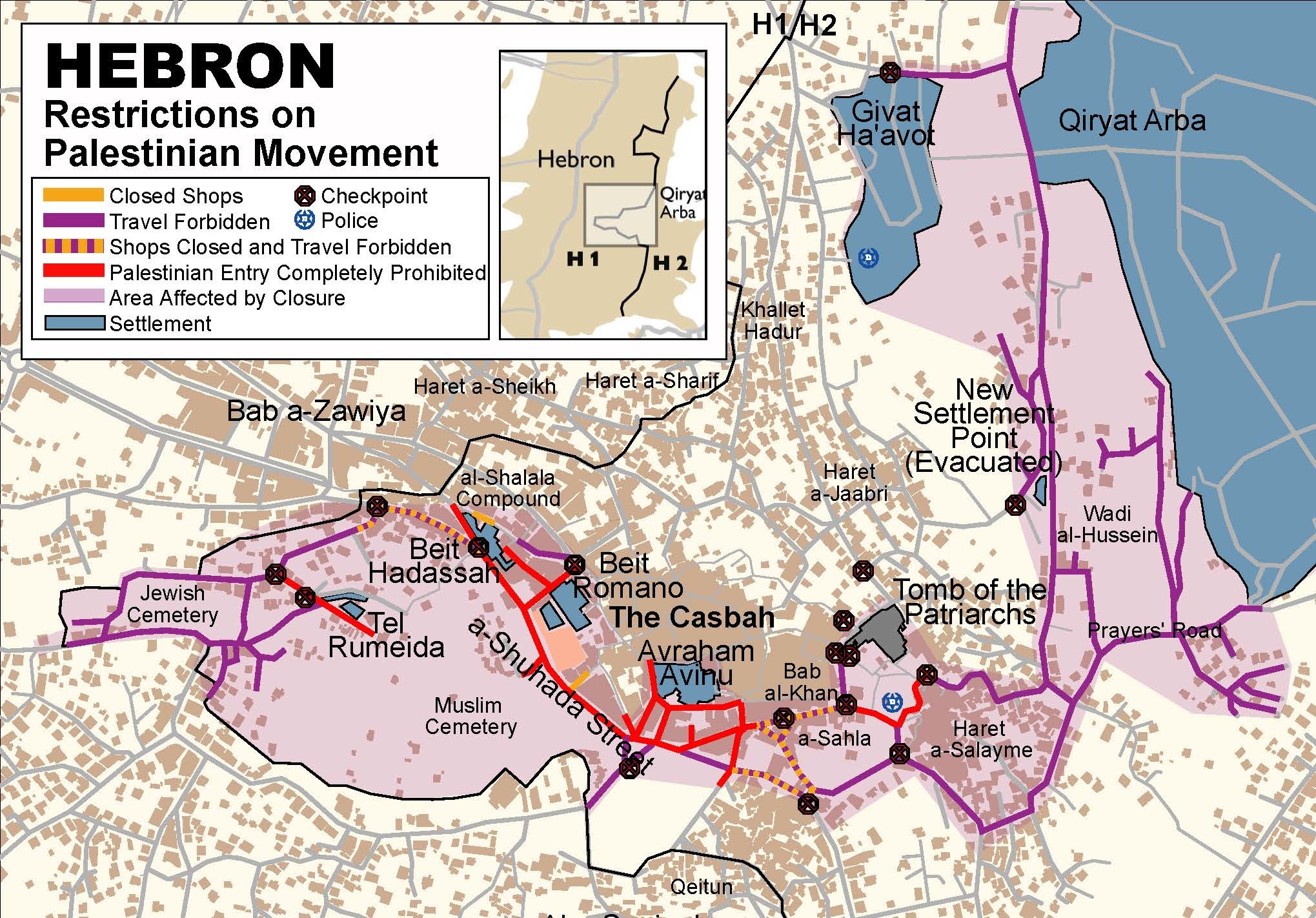

In 1993, during the Yugoslav wars, architect and former mayor of Belgrade Bogdan Bogdanović coined the term “urbicide” to describe the destruction of Balkan cities. Serbian nationalism romanticized rural villages, where a single community spirit could predominate. Conversely, the city, was a symbol of communal and cultural multiplicity; the antithesis of the Serbian ideal. In the Palestinian occupied territories, the entire landscape has been targeted. The weapons of mass destruction used against it are not so much tanks as they are bulldozers, destroying streets, houses, cars, and dunam after dunam of olive trees. This is war in the age of agoraphobia—the fear of space—seeking not the division of territory but its abolition. A trail of devastation stretches as far as the eye can see: a jumble of demolished buildings, leveled hillsides and flattened wild and cultivated vegetation. This barrage of concentrated damage has been wrought not only by bombs and tanks but by more industrious forms, toppling properties like a violent tax assessor.

Refugee Heritage conversations is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and DAAR (Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency)