CARTHA on The Possible Progress

Call for papers

April 22–July 31, 2019

For the editorial cycle of 2019, the departing question is “What can Progress be?”, inviting contributors to approach the topic of progress through concrete case studies, opinion pieces or visual essays.

Progress

“L’amour pour principe, l’ordre pour base et le progrès pour but”

“Love as principle, order as basis, progress as goal”

–Auguste Comte

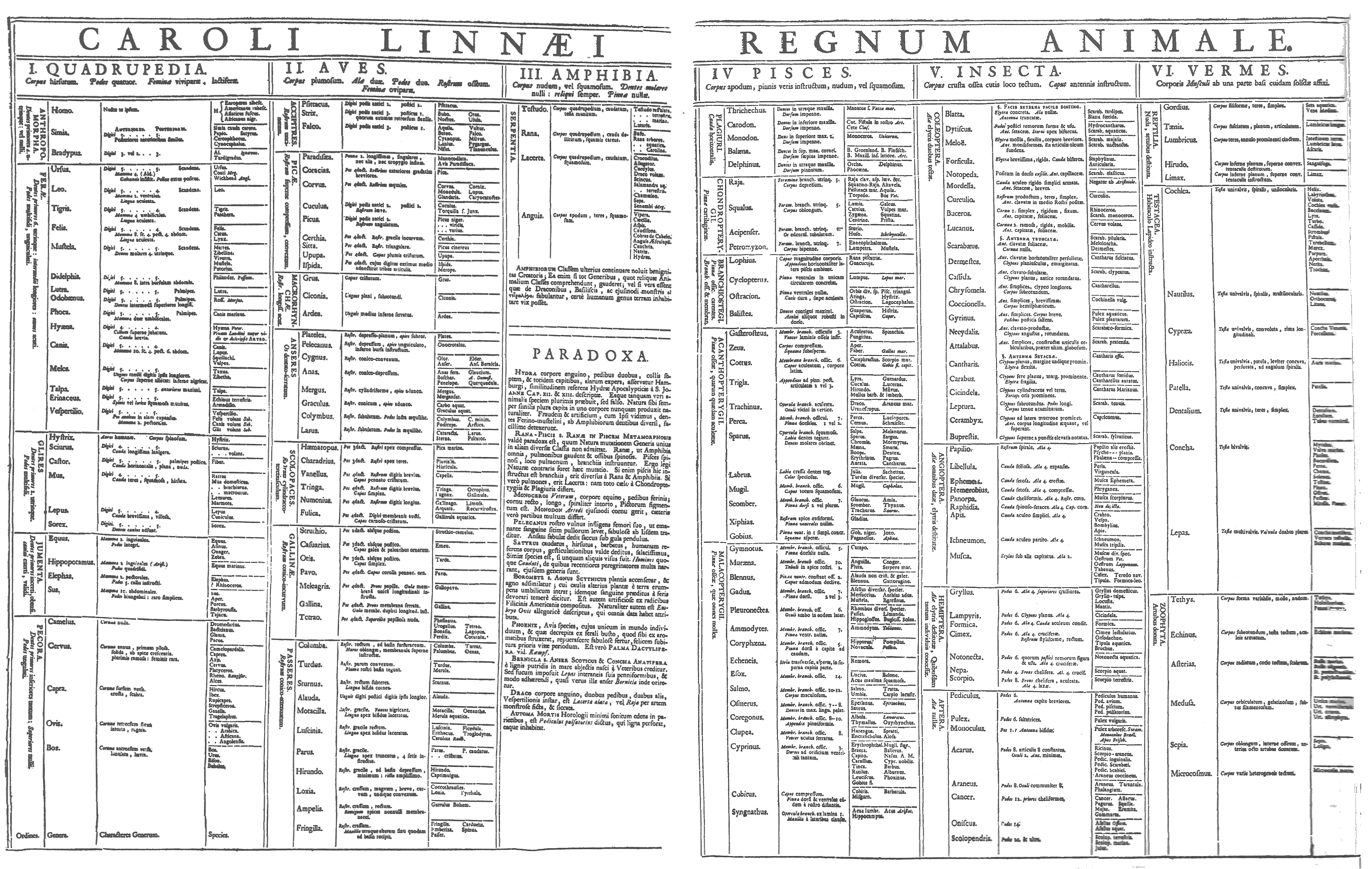

The Positivist Stage, as stated by Comte, marked the entry into an era when, due to gradual but constant scientific developments, increasingly accurate predictions of the future could be done. But this entry has also prompted a new condition, in which the consequences of the steps being taken towards certain a destination contained the potential to lead mankind into a more precarious situation than previously. Comte defines Progress as the “goal.” But can one understand progress without knowing which, what, or for whom the goal is?

Scientific assumptions and cultural constructions

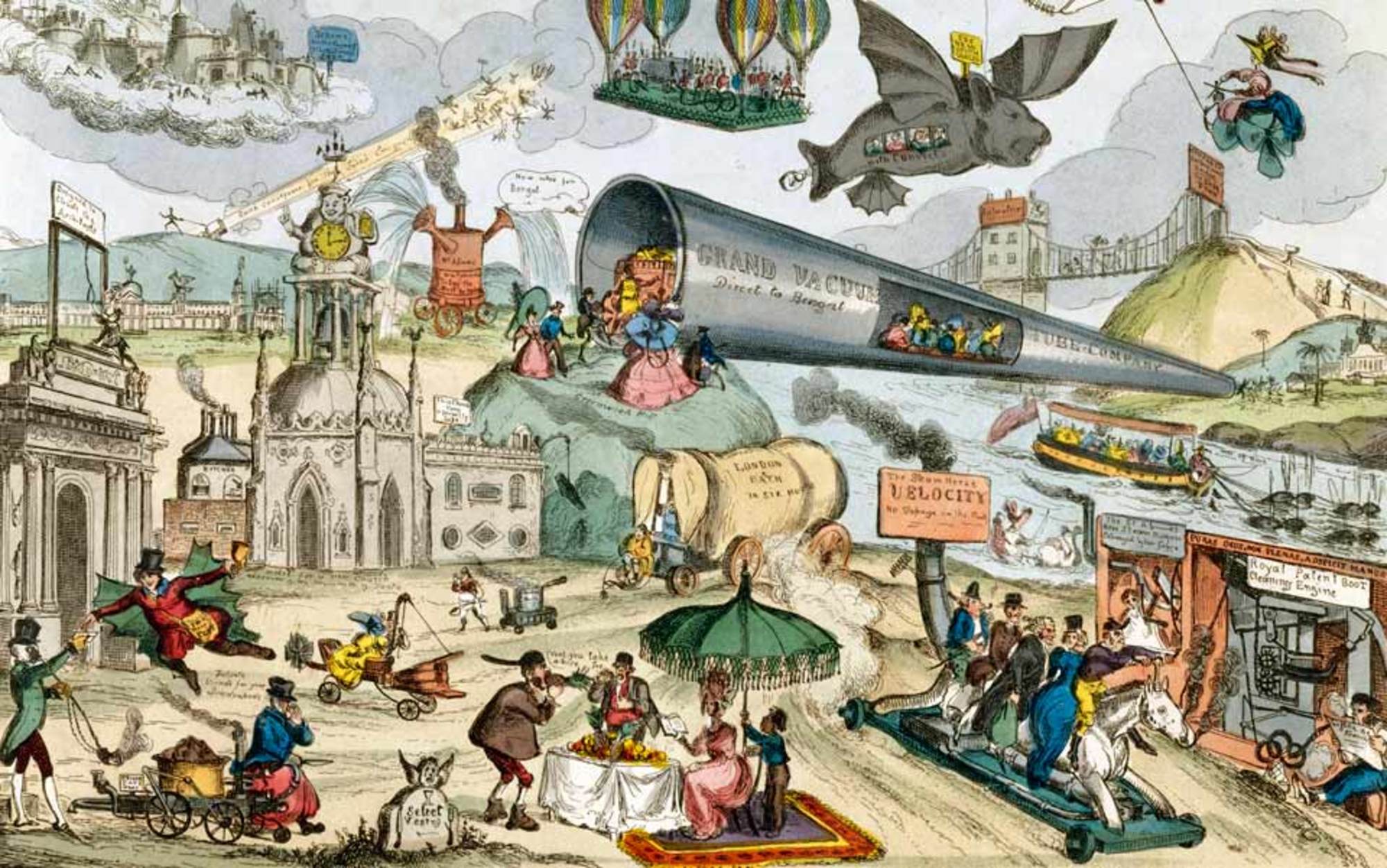

During the past two centuries, narratives around the future developed into the offer of scenarios containing possible solutions to current problems at a given moment in time. The notion of progress became a tool for the definition of desired behaviours, implying either that the future will be necessarily better or that a certain course of action will lead us to a worst-case scenario. It seems difficult to reach an agreement on which ideals we should aim for but, regardless of the ideas behind a certain position, technological progress is mostly seen as one of humanity's great hopes.

Though scientific advances do definitely influence the notions of progress, progress itself seems to be far from scientific. Rather than a straight line, freed from “the silence of envy, or the caprices of fashion,” progress is a rather sinuous, fluid string that fluctuates according to the tides of political intentions. Utilitarian notions of speed, amount, range, volume, brightness, size, etc. keep being revisited and reappropriated, according to the prevalent views of the day on the correct direction to move towards, pushing habits and conventions along with the sliding shell of a fragmented cornucopia. On October 24, 2003, Concorde flew its last commercial flight. Ultimately it was retired not because of the catastrophic accident in Paris in 2000, not because it was not profitable and consumed gargantuous amounts of fuel, nor because it could no longer fulfil its initial functions, but due to the subsequent unbearable noise caused by the breaking of the sound barrier. Its supersonic nature—heralded as the future a mere 27 years earlier—ended up being the reason for its failure.

This shift in perception of noise is closely connected with the evolution of the broader political and technological landscape. After all, the effects of the supersonic jump have not changed (neither have the fuel consumption of the planned costs per trip). What changed was the relevance and scope of the voices of the people and property affected by Concorde’s flights. New media brought enhanced visibility to anything witnessed by anyone with a device to hand. It rendered governments either liable or responsible for ensuring justice, first in the compensation for the damages and, later on, for assuring the comfort and quality of life of those affected. This very symbol of British design and scientific excellence in an era obsessed with speed and distance was sacrificed by the political forces in the name of a society focused on comfort and safety.

Static vs. Fluid

Shifting goals means shifting notions of progress. But progress—since the Enlightenment, at least—inherently contains the paradoxical nature of change being the key for the development towards an improved or more advanced condition. How does this implicitly fluid characteristic relate to the built environment?

The Positivist Temple in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, a remnant of the church based on Comte’s semi-lunatic proposal for mankind, serves as an example of the volatile nature of the notion of progress: it borrows its typology, structure, form, materials, function and identity from the Neoclassical churches built at the time. Though Comte was aware of the non-linear character of the stages, pointing out the necessarily conciliatory nature of Positivism, the ambiguity in the architecture of a building which is supposed to be the embodiment of progress, seems to go beyond the acceptance of said ambiguity, rather questioning the possibility of progress itself.

The Possible Progress

Perceiving architecture as a synthesis of the ideals and technology of society, positions architecture as a privileged barometer of the movement towards disparate notions of progress at different times. Departing from this position, with this cycle, we wish to present a current definition of possible progress through a positivist lens, by addressing the following questions:

–What is Progress?

–Progress as process or Progress as destination?

–Which visions of Progress have had a striking influence on the conceptualisation, construction and perception of architecture? When, why, how and through which projects?

–Which role does architecture play in the construction of new paradigms of Progress?

–Instrumentality: Reactive vs Instrumental?

–Progress vs. Innovation ?

–Is Progress even possible?

Schedule and submission details

–Deadline: July 31, 2019

–Proposals for contributions should be electronically sent to: info@carthamagazine.com.

–Accepted proposals will then be prepared for publishing in collaboration of the author and the editorial board.

–Different interpretations of the topic and its processes are possible and encouraged by the editorial board.

–Submissions must be written in English.

–Contributions can be submitted without any text formatting. All texts must be written in English (max. 1500 words) and submitted as .rtf files. All images must be submitted as individual files (.jpg) at 300 dpi and at 72 dpi. Captions should be submitted alongside the images.

–CARTHA does not acquire intellectual property rights for the material appearing in the magazine. We suggest contributors publish their work under Creative Commons licenses.

Further information and previous editorial cycles on our website and in the following books:

CARTHA On Relations

published by Park Books.