Masquerade: On the success and failure of institutions

I don’t want to go to the office. When thinking about going back my body reacts in the same way as in third grade, when I was about to have math class with Prof. Don Manuel. Today someone mentioned that I was not alone—like years ago, during a school reunion I learned that I wasn’t the only one suffering the authoritarian-induced stomach-pain. Apparently, many workers don’t want to go back to their offices and prefer, instead, to continue doing their thing from home, as they have during the last months of self-isolation.

I know, I am talking about a particular section of the population that, despite their pain in the stomach, is in a quite comfortable situation. Yet, I wonder what happens to those and other bodies that don’t want to go back—to the office, and to the status quo.

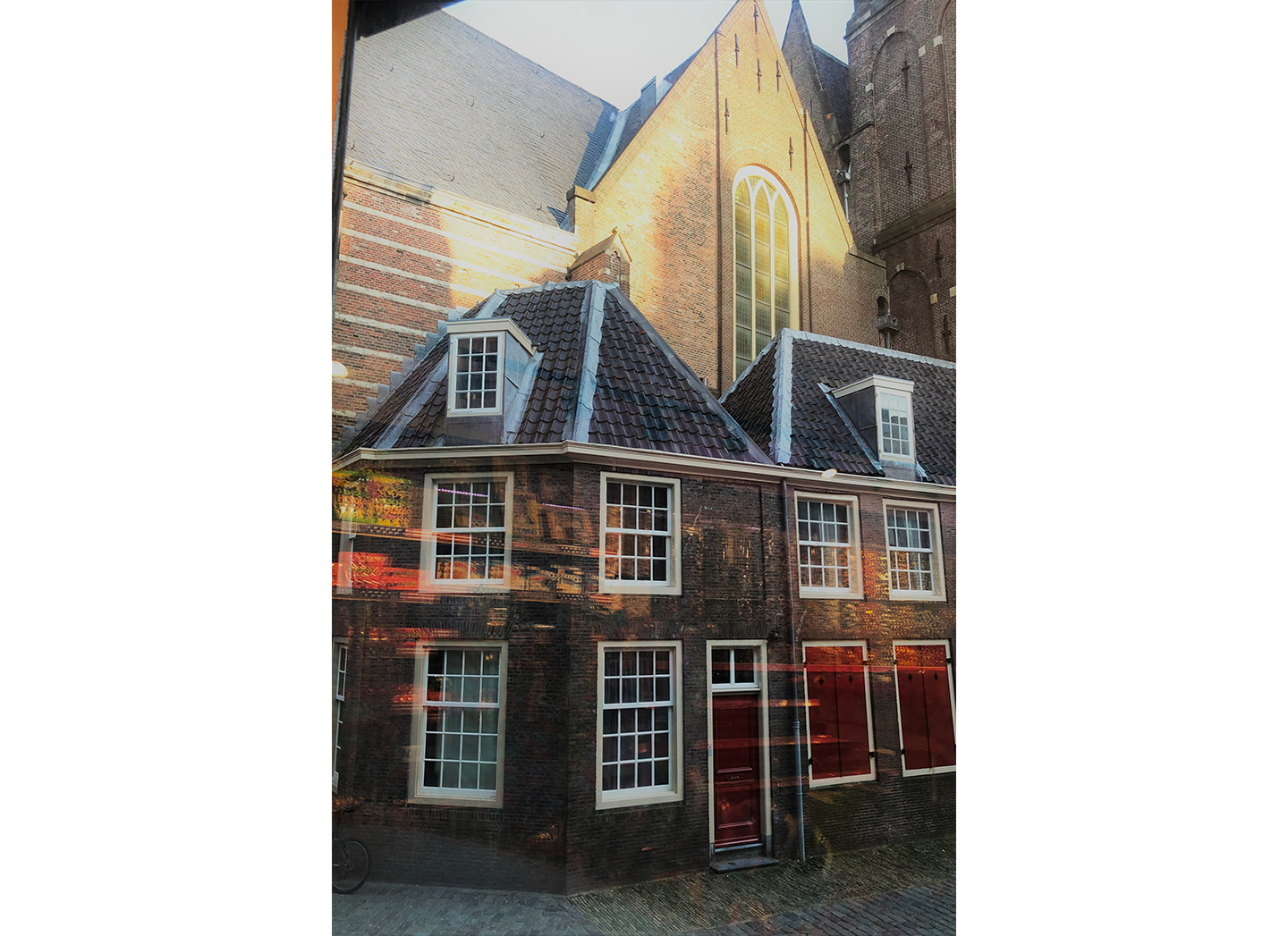

Sometimes we take architectures and their conventions for granted. The pandemic gave the possibility to look at our working spaces and routines—in this case offices at cultural institutions—with some distance, and ask: How does it feel to be there? What does it do to bodies? What and how does it urge them to perform?

Institutions are, generally, places where we don’t expect people to be themselves. Upon entering them, bodies are hosted, invited to perform according to particular spatial politics. Their experience is actually regulated by codes of conduct and social behaviours. Even if these guidelines are enacted for the sake of ethical coexistence, the relations they establish are, most of the times, extractive. For too many institutions are still rooted in principles targeted against certain bodies and practices.

Talks and trainings on diversity, inclusivity, and safe spaces proliferate in predominantly white institutions. Feminist and queer perspectives are deployed to alleviate the shame of maintaining male-led structures. Perhaps, as Felix Guattari suggested while conducting “institutional psychotherapy,” institutions are ill, and it is necessary to treat them before they treat or assist others by “replacing bureaucracy with institutional creativity.”(1)

Didn’t I know this before the COVID-19 pandemic? Of course, I did. I was aware of the pain of many people who felt uncomfortable, unwelcomed, awkward in these interiors, and who trusted me with their personal experiences. I’ve also been part of initiatives focused on mitigating this pain. Yet, not only I failed too many times, but also, by being immersed in the daily production mode, I didn’t pay attention to the discomfort brought by my search for institutional attachment, one that would have kept me even more alert.

While family, religion, or nation were not my immediate choice for an institutional identity, I longed for the security ostensibly enjoyed by those with a strong sense of belonging. I finally opted for architecture. And the architectural discipline led me to work in and on its operative institutions. Since, I have flirted with the impossible position of the foreigner, the misfit, or the one who simply doesn’t fit in. After years testing and studying alternative formations—decentralized models for universities, evanescent museums, more-than-human cooperatives—I came to the conclusion that my so-called critical work has served, too often, to legitimize existing institutions. To introduce the small changes that make them—and the pain they create—bearable enough to avoid their collapse.

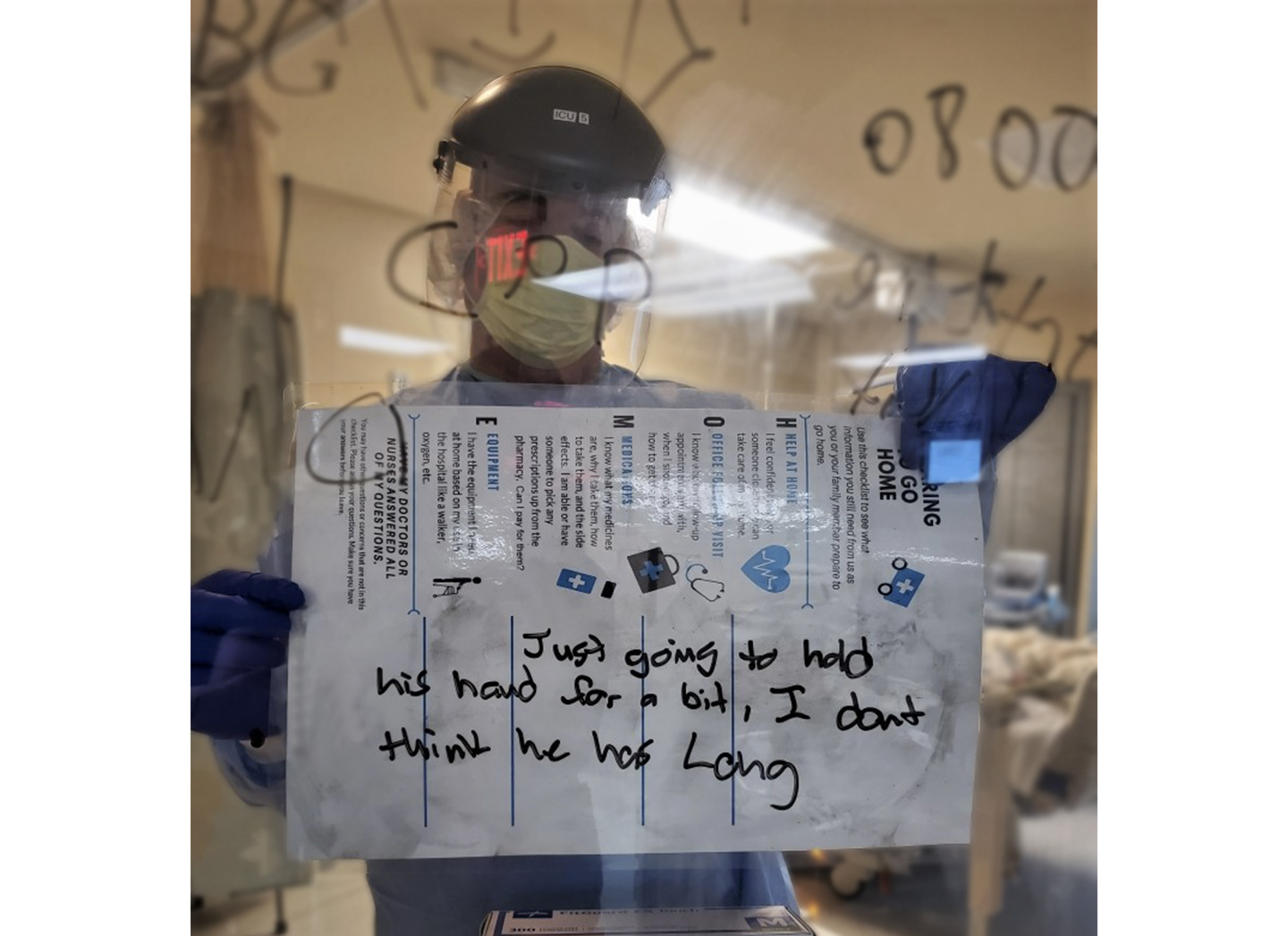

Why, then, do I continue to believe in institutions? Why—after seeing the forms of control? Why—knowing that institutional bureaucracies and efficiency dogmas prevent the uncompromising interpersonal attention and affection that care relies on? Why do I continue to work in institutions? While feeling anxious by the perspective of going back to the masquerade and entertained by my white-lady ruminations, others have already taken action.

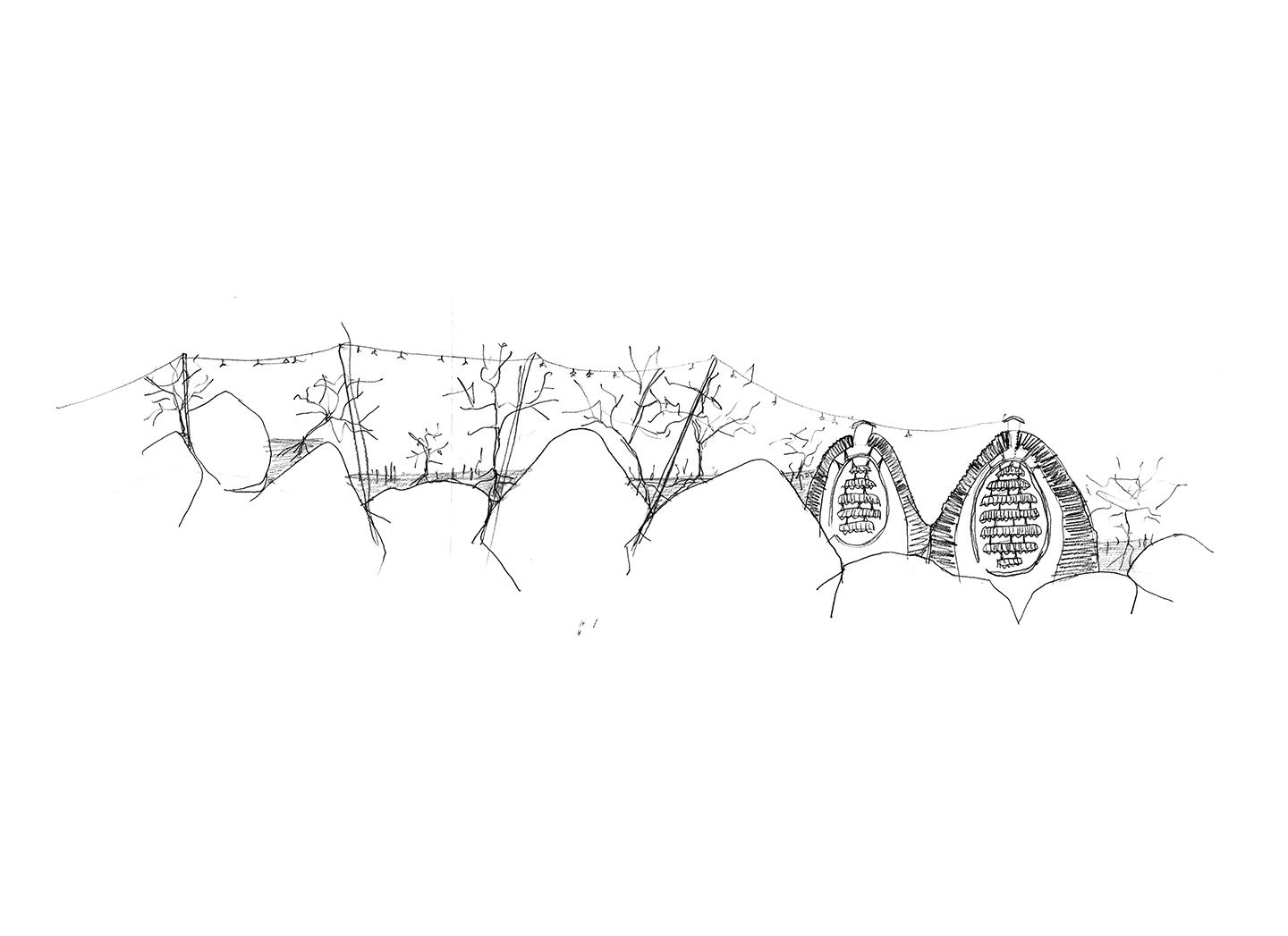

Groups of artists, activists and cultural agents are weaving structures of solidarity and creativity in the interstices of the city of Rotterdam. They are reclaiming existing institutions, infusing them with different vocabularies, conventions, and methodologies; with new affections.

They are challenging the democratic imaginaries of existing institutions, showing the bodies and territories bypassed by their normative systems.

They are exposing the violence inherent to the spatial and aesthetic choices that have permeated institutional practices to the point of remaining unnoticed for many of us who administer them.

They are overcoming the gap between the population with easy access to traditional institutions, and those who simply don’t feel welcome in them.

They are deploying their wounds to defy the very institutions which have historically imposed systems of patriarchal, colonial subjugation and dispossession; to expose the relation between past and ongoing forms of xenophobia and racism, as well as systemic underrepresentation.

Their initiatives are impregnated by the sense of the instability endemic to life in diasporic communities, bearing symptoms of dislocation across generations. Yet, this time, the instability is an asset. Seemingly temporary, these unassuming institutional takeovers serve to channel the disruptive powers of imagination; to enhance the politics of recognition; to mitigate institutionalised violence with forms of collective care. They are equally mobilized for practical problems and emergent thinking. And instead of stomach pain, they harvest the most enduring energy.

I am talking about the work by Amal Alhaag, Nash Caldera, Furtado Melville, Gyonne Goedhoop, Egbert Alejandro Martina, Malique Mohamud and Concrete Blossom, Aissa Traore, among others. Their actions and efforts are a mirror to existing cultural institutions, and those, like me, who work in them. They urge the older centers of power—largely disconnected from the urban realities that surround them—to evolve and do the groundwork. To dismiss the traditional hierarchical models based on unequal exchange. Or instead, to make way.

Marina Otero Verzier is an architect based in Rotterdam. She has worked in academic and cultural institutions in the US, the UK, and the Netherlands. Her PhD thesis Evanescent Institutions (2016) examines the emergence of a new paradigms for institutions, and in particular the political implications of temporal and itinerant structures.

(1) Félix Guattari, Psychoanalysis and Transversality: Texts and Interviews 1955–1971(1972), trans. Ames Hodges, (Semiotext(e)/MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 2015), p. 62, 17, 214.