Browser, beware: # 22: LIBRARY

And when he grasped me by the hand he put in poetic words the ultimate expression of Persian hospitality: “Chadam rouyeh tchashm” — “You may walk on my eyes.”Strange Lands and Friendly People. William O. Douglas. New York: Harper, 1951

Browser, beware: Bidoun 22: LIBRARY

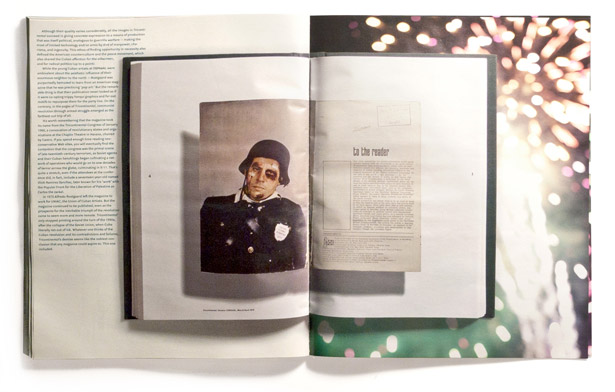

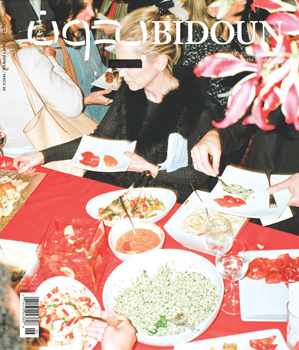

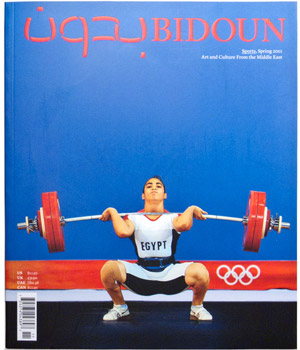

The first thing you notice about the new Bidoun is the cover: a matte off-white surface with a photograph glued to its center. It might be black-and-white or colorful, pristine or blurred or torn along the edges. It might depict a portrait or an action, a business meeting or a wedding, maybe an accident. We have no idea, actually: we’ve never seen most of them, and probably never will. A friend of the magazine in Cairo purchased five thousand photos from flea-markets in Cairo and sent the lot of them directly to our printer, who glued them onto the cover and sent them out into the world, eliminating the middleman: us.

We all sit on the floor, trying hard to enjoy the traditional Arab feast — a sheep whose teeth grin macabrely on its platter. The Americans shower oily compliments on the host… Not a business word crosses the sheep’s teeth, but the spectre of money hangs over us all.

Super-Wealth: The Secret Lives of the Oil Sheikhs. Linda Blandford. New York: Morrow. 1977

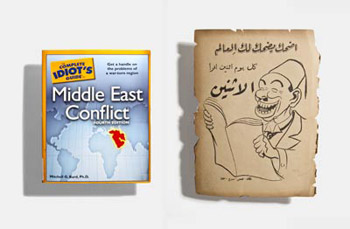

This gesture — plundering one set of incidental archives to create another — seemed an appropriate way to herald the latest issue of Bidoun, which considers that ever-expanding entropy, the library. Building on Bidoun Projects’ recent exhibition at the New Museum for Contemporary Art in New York, we present a reading of five decades of printed matter, carefully selected with no regard for taste or quality, in an attempt to document every possible way that people have depicted and defined — slandered, celebrated, obfuscated, hyperbolized, ventriloquized, photographed, surveyed, and/or exhumed — that vast, vexed, nefarious construct known as “the Middle East.” The result is banal and offensive, a parade of stereotypes, caricatures, and misunderstandings of a sort that rarely makes it into the magazine, all the trappings of the Middle East as fetish: veils, oil, fashion victims; sexy sheikhs, sex with sheikhs, Sufis, stonings; calligraphy, the caliphate, terrorism; Israel.

She went up. I immediately placed myself under her and she came down in a perfect one-point landing. My control tower signaled that we’d made full contact. In fact the message shot through me in all directions.

Coxman #24: Turn the Other Sheik. Troy Conway. New York: Paperback Library, 1970

This particular collection of books was the outcome of a series of escalating searches on the World Wide Web. Deploying a search term like “oil,” “Arab,” or “Middle East” returned an unmanageable array of books — but adding an additional search term would narrow the field in telling ways. Books about oil before 1973 that cost less than five dollars are few and almost entirely in hardcover, usually technical guides written for a specialized audience. After 1973, the same search yields a completely different array: in hardcover, hundreds of books about the coming oil crisis, rampant Arab wealth and influence, global bankruptcy, impending world war, and biblical Armageddon. At the same time, in paperback, the terrorist novel is born, and its brood is legion — cover after cover depicting vintage special agents, Israeli commandos, vigilante lone wolves, soldiers of fortune, and even a black samurai, each karate-kicking djellaba’d sheikhs beside burning oil rigs, often after sampling the delicacies of the inevitable harem. A similar set of searches substituting “Iran” for “Arab” produced its own assortment of types and stereotypes. We wanted to see what would happen if we put together a library without regard to aptness or excellence; if we chose books not for their subjects, but their contexts; not for their authors, but their publishers; not for their qualities, but in their quantities.

Important innovations in the technique of assaulting banks have developed, guaranteeing flight, the withdrawal of money, and the anonymity of those involved. Among these innovations we cite shooting the tires of cars to prevent pursuit; locking people in the bank bathroom, making them sit on the floor; immobilizing the bank guards and removing their arms, forcing someone to open the coffer or strong box; using disguises.

“Minimanual of the Urban Guerilla,” Carlos Marighella. Tricontinental 56, November 1970. Havana: OSPAAL

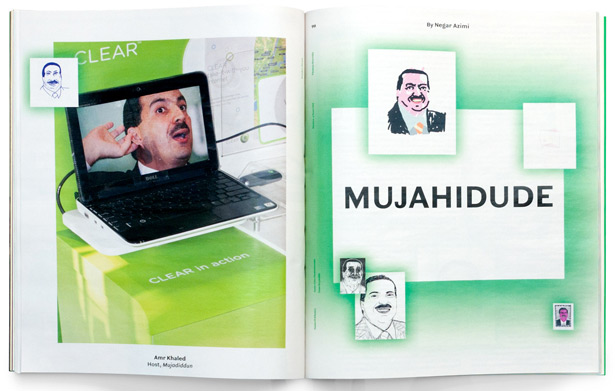

While much of the issue reproduces materials from the Bidoun Library and the catalogs that attended its New York iteration, three features explore the backstories behind some emblematic books and periodicals.

Many of the materials in the library were produced in conjunction with one or another corporate entity, including a variety of airlines and telecomm behemoth ITT. But the strangest flower of corporate publishing is undoubtedly Aramco World, the curiously spectacular official publication of the Arabian American Oil Company. See “Mondo Aramco,” an oral history of the Middle East’s oldest magazine for art and culture.

I was a big hiker and I knew that the Lebanese government didn’t like goats in the forest — goats rip things out by their roots, whereas sheep just crop things. So I pitched a story about reforestation efforts in the mountains and that appeared in the second issue [Aramco World] published in Beirut.

—William Tracy, “Mondo Aramco”

One category that intrigued us was books printed by regimes of production that no longer exist. Like the myriad publications of the Novosti Press Agency in Moscow, such as Afghanistan Chooses a New Road, Treasures of Human Genius: The Muslim Cultural Heritage in the USSR, and Tonight and Every Night: The Soviet Circus Is Seventy Years Old. In “Invitation to a Sunset,” Achal Prabhala remembers another communist publisher, Progress Press, and the warm Red tinge of his Indian boyhood.

It was like entering a time warp. Everywhere around me were the books of my youth, and then some. Progress Publishers, Moscow’s finest party press, used to flood our shores with books for all ages, Folk Tales of the Ukraine for the tots and Das Kapital for the tottering.

—Achal Prabhala, “Invitation to a Sunset”

The Cold War produced publishing ventures across the globe. Post-revolutionary Cuba became for a time a hotbed of avant-garde publishing, sponsoring the Afro-Asian-American journal Tricontinental, which included foldout posters promoting a solidarity-of-the-month club with oppressed guerrilla movements the world over. Copies were door-dropped on college campuses across the Third World, including Beirut, where Bidoun acquired some thirty-odd copies for fifty cents each. In “Revolution by Design,” Babak Radboy considers the aesthetic legacy of Tricontinental and its visionary art director, Alfredo Rostgaard.