e-flux journal issue 115

with Fahim Amir, Jace Clayton, Sven Lütticken, Ariel Goldberg and Yazan Khalili, Sonali Gupta and H. Bolin, Xenia Benivolski, Nikolay Smirnov, J.-P. Caron, and Imogen Stidworthy

This week in Russia, Alexei Navalny was sentenced to over two years in prison, partly for violating parole while in a coma from a state-sponsored murder attempt. Following a week of large-scale demonstrations across Russia protesting his arrest, the skilled lawyer and anti-corruption activist stood in court before his sentencing and stated, “I hope very much that people won’t look at this trial as a signal that they should be more afraid. This isn’t a demonstration of strength—it’s a show of weakness. You can’t lock up millions and hundreds of thousands of people. I hope very much that people will realize this. And they will. Because you can’t lock up the whole country.”

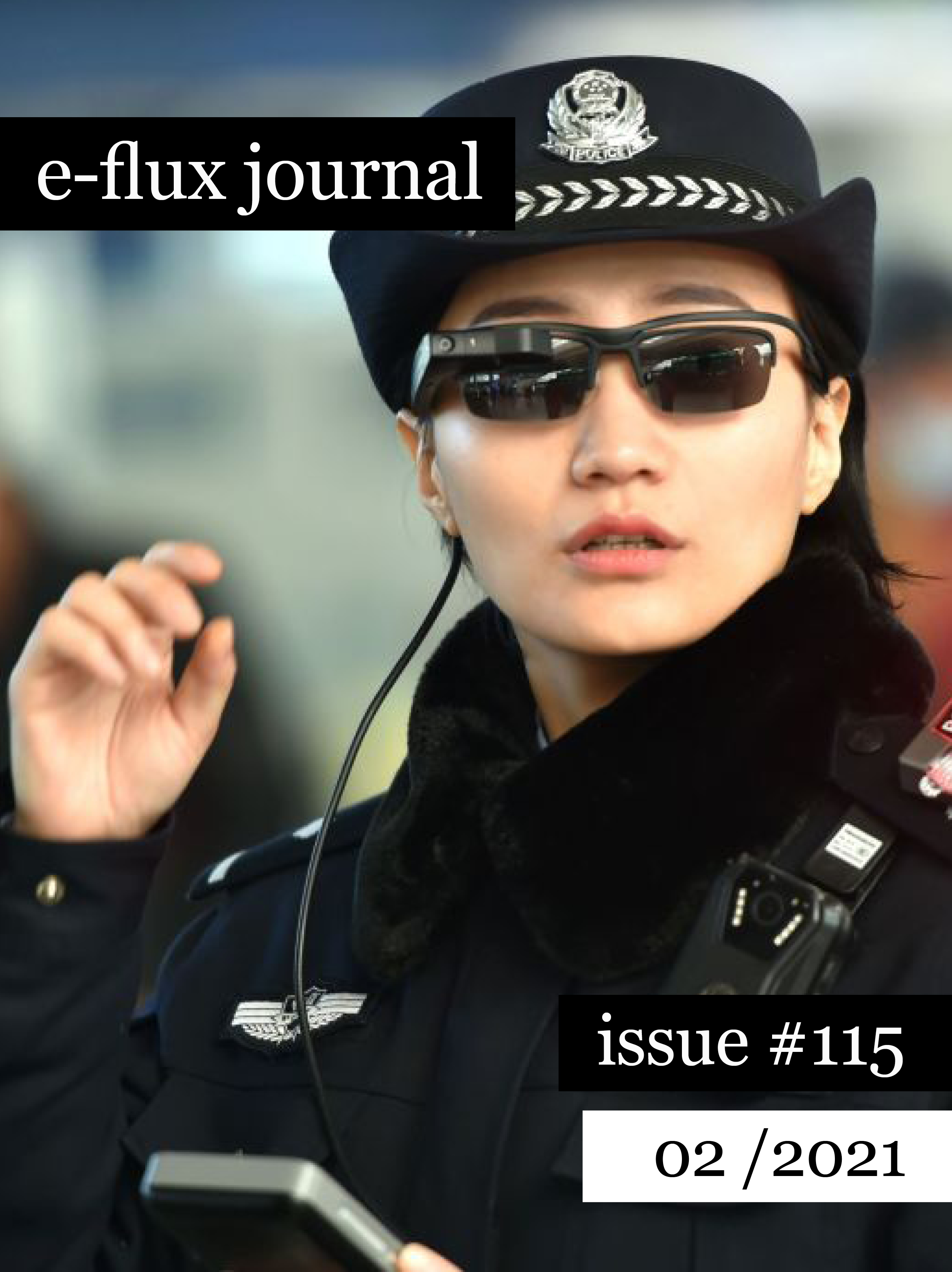

In this issue of e-flux journal, Ariel Goldberg and Yazan Khalili reflect on photographic images’ ties to violence, surveillance, and the state—“the camera that eats all other cameras.” In their essay “We Stopped Taking Pictures,” the recently appointed cochairs of the photography department at Bard’s MFA program explain the irony of their own coincidental decisions to stop taking pictures by identifying a vastly expanded photographic regime that the field must now account for. Today, the two photographers who stopped taking pictures teach their graduate students through photographic media (webcams) about the double-edged sword of surveillance—the CCTV footage from cameras Palestinians install to prevent theft that are also used by the IDF to surveil them, or the cop who kills regardless of his body camera or the bystander filming him. The overabundance of photographic documentation makes harder questions necessary. For example: “How can one photograph laws, these less visual forms of violence that remain the status quo?”

Jace Clayton replays Meriem Bennani’s video of a pale crowd at the US Capitol—but the one that sang there in triumph (or in this version, screamed) four years ago, not last month. Despite all that’s horrible now, including the fact that “the crumbling nation-state is inhabited by networked communities that no longer share a remotely consensual reality,” Sven Lütticken looks deeply into the present (and recent past) for, among searing critiques, signs of emergence and potential possibilities.

Two essays in this issue round out the special miniseries co-commissioned by Katia Krupennikova and Inga Lāce as part of “Survival Kit 11 (Being Safe Is Scary).” In addition to Goldberg and Khalili’s text in the series, Imogen Stidworthy, an artist and filmmaker, brings together fragments of her work and relationships with language amongst people on and around the spectrum of nonverbal autism.

Nikolay Smirnov peers into the history of Russia’s cultural and religious immanentism—a family of syncretic worldviews rejecting Abrahamic religious transcendence in favor of the immanent physical world of “earth, cosmos, ecumene, material environment, or social relations.” Fahim Amir’s “Cloudy Swords” encounters a colonial avant-garde of honeybees spreading with white settlers in America, mosquito armies that recall past colonial panic and present viral dilemmas, and insects determined to colonize the colonizer in the twentieth century.

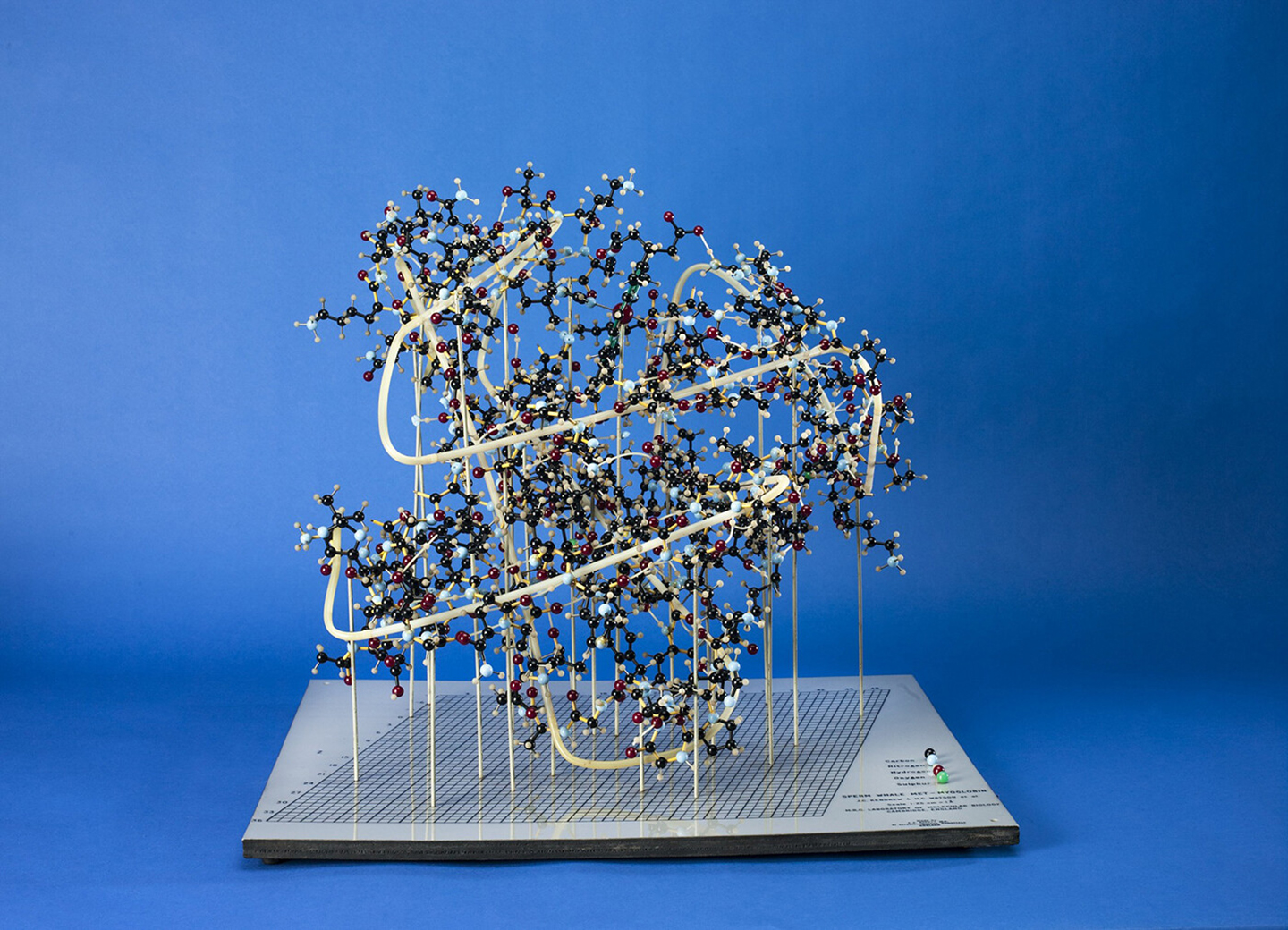

J.-P. Caron traces world-making and world-unmaking between sci-fi, the philosophers Nelson Goodman and Peter Strawson, and the constitutive dissociations of Henry Flynt. Xenia Benivolski writes on Dora Budor’s The Preserving Machine, an ongoing installation based on a Phillip K. Dick story about a scientist’s desperate attempt to use animals and insects to preserve European music. This is an entryway to tracing human relation to birdsong, which reveals “otherwise invisible political interventions into landscapes and soundscapes.”

Sonali Gupta and H. Bolin urge us to understand the coronavirus beyond good and evil, through fugitive mechanics, and on the farther side of the calculus of survival—“in a manner that neither applauds the virus nor remains paralyzed by fear, uncritically accepting state measures of control and austerity in hopes of a return to normal.”

—Editors

Fahim Amir—Cloudy Swords

While bees are currently esteemed as universally valued bringers of life, there is another insect that can’t be left off of any Buzzfeed listicle of the world’s deadliest animals: the mosquito. No other animal accounts for as many human fatalities as this insect. That’s why the eradication of mosquitoes is a typical focus of philanthropic initiatives, from the Rockefeller Foundation to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. But what if the front lines are not so clear-cut?

Jace Clayton—That Singing Crowd

Bennani replaced the singing with canned screams and nothing else. There’s no faint rustle of the crowd, as in the original footage, for example. Nor has she applied any reverb, which would create the effect of the vocalists inhabiting the same acoustic space. All the members of this choir howl in isolation—from the world (there’s no diegetic sound) and from each other (there’s no reverb). A crowd vocalizing with none of the subtle audio cues that let us know we are in a crowd: Bennani’s audio treatments mirror the eerie social alienation that is only possible in digital domains.

Ariel Goldberg and Yazan Khalili—We Stopped Taking Photos

A photo hides more than it shows, which is merely the physical and reflective light of the world: bodies in a place, scars on skin, a wall in a landscape, a person holding a book, fireworks at night, trees, four people hugging each other in a joyful moment, a boy looking at his drawing, a policeman shooting at demonstrators. We have seen all of that, we have photographed it, but what about the unphotographable violence that goes through the image without leaving a trace in it, the systematic violence that is normalized within life itself, the pain of the forest, the law that doesn’t allow your child to get a birth certificate, the fear of being profiled, of not being allowed to travel, and the bureaucracy of everyday life?

Sven Lütticken—Divergent States of Emergence: Remarks on Potential Possibilities, Against All Odds

After decades of There Is No Alternative ideology, we see a pathos of the possible that aims to quell fears about empty possibilities without potentiality. But what are the potential possibilities—as opposed to largely hypothetical ones? In Peter Osborne’s characterization, the space of art is project space, and hence the space of the projection of possibilities and the presentation of “practices of anticipation.” And indeed, much contemporary aesthetic practice is possibilist—from speculo-accelerationist “we were promised jetpacks” retro-Prometheanisms to various forms of social and political practice seeking to foster and form alternative forms of assembly and cooperation.

Sonali Gupta and H. Bolin—Virality: Against a Standard Unit of Life

The virus exists in the liminal space between life and nonlife. A small amount of genetic material contained within a perfectly geometric molecular envelope is somehow able to self-propagate, manipulate its environment, adapt, and evolve—all features we might find evocative of life. And yet, a virus does not breathe. Whether you call it prana, qi, or basic biochemistry, respiration is simply a metabolic process of energy transduction. The smallest entity capable of breath is the cell—perhaps why we designate it as the “fundamental unit of life.” The final utterances of Eric Garner and George Floyd, “I can’t breathe,” reflect the singular experience of blackness in America. Yet, these words also echo within us like a phantom pain as a global pandemic chokes the life out of millions and uncontrollable wildfires decimate forests—the lungs of the earth. In this planetary asphyxiation, we look to that which does not breathe but nevertheless remains animated—the virus.

Xenia Benivolski—You Can’t Trust Music

Music reflects changes in the world: its mechanism relies on making noise palatable by means of subjectively defined order. The dialectic between order and violence mirrors another dialectic between music and pure noise: each reveals hidden physical and social architectures. By examining degrees of deviation from order, one can decipher the social code of a society at a particular time.

Nikolay Smirnov—Elements of Immanentism in Russia: Double Belief, Cosmism, and Marx

Popular religiosity, Sophiology with its Fedorovian, cosmist charge, and the alchemical unconscious of Marxist theory are the three distinct but in some ways related “holy families” of Russian immanentism. On the level of ideas, the various members of these families are easily coupled and hybridized, despite their heterogeneity. In consequence, we witness the emergence of a kind of ideological field of integral immanentism in the first decade of the twentieth century.

J.-P. Caron—On Constitutive Dissociations as a Means of World-Unmaking: Henry Flynt and Generative Aesthetics Redefined

For Flynt, structure art involves an underdevelopment both of structure and of the sensible content of the art. This results from the mutual tethering of one to the other. Insofar as music seeks to satisfy both poles (structural and sensible/musical) at the same time, both are diluted: structure becomes impoverished as it needs to be incarnated in sounds, and music becomes impoverished to the extent that it obeys a logic external to sounds themselves. Concept art is a way of releasing the abstract structure from the sensible carcass; when concepts are freed from incarnation, it is possible to create more complex and interesting logical structures.

Imogen Stidworthy—Detours

Losing a sense of bodily boundaries can happen when we are dancing, attuned to another person, or immersed in nature. Many people on the autistic spectrum describe intense feelings of a “leaky sense of self”: becoming confused with other people or with one’s surroundings, losing or having no sense of being “me,” in ways that can sometimes be existentially threatening, but also exhilarating, liberating, and joyful.