The Happy Face of Globalization

Opens this Saturday 21 July, 2001, 19.00 hrs

Biennial of Ceramics in Contemporary Art

ON THE OCCASION OF THE G8 SUMMIT IN GENOA, ITALY….

The Happy Face of Globalization.

Biennial of Ceramics in Contemporary Art (1st edition)

Albisola (Italy)

Curators: Tiziana Casapietra and Roberto Costantino

The Art of Lilliput

For many, the word ‘globalization’ is unpalatable, and rightly so. The term conjures up a nightmare scenario: the planetary expansion of a ‘meat-grinder’ capital blitzing specificity at a local and national level, coupled with the violence of capitalist domination which sees manufacture de-territorialized and thriving on an underpaid workforce, all of which ensures that consumerism continues apace and unchecked.

Globalization points to an overridingly uniform culture at a planetary level, and the disappearance of local cultural traditions. Using this as our starting point, the exhibition we have curated at Albisola sets out to hypothesize a proliferation of the antibodies needed to resist just such a threat. To pick up on Jeremy Brecher and Tim Costello, this exhibition comes with a sort of Lilliputian strategy.

In Swift’s satirical tale Gulliver’s Travels, the tiny Lilliputians were able to capture the predatory Gulliver, so much bigger than they, by tying him down with hundreds of ropes as he slept. Costello and Brecher agree that the Lilliputian strategy mirrors the strategy being carried out today by the multi-nationals: “Just as the strategy carried out by these companies creates worldwide production networks by harnessing together many separate companies, the Lilliputian strategy envisages a cogent local organization of reciprocal assistance and strategic alliance with similar movements from all over the world”.

Playing the globalization card to one’s own advantage means making your exhibition into a similar spatial-temporal compression that eliminates distances and sets its aims at instant global communication, not unlike the internet, thus bringing together, locally, a multitude of localisms: this involves flying in the face of the overriding cultural homologation and uniforming that quashes difference and promotes multicultural exchange in a spirit of hospitality as offered by a local tradition such as Albisola’s ceramic history: in short, experimenting at a local level with the temporary cohabitation of the heterogeneous and conflicting interests which characterize the ‘new world disorder’.

Globalization promotes physical mobility and the transformation of localities. It is towards this dimension that Albisola today is poised. The town can boast an internationally-acclaimed avantgarde past, and this exhibition aims to be an extension of the town’s twentieth century avantgarde legacy. This Biennial is an attempt to allow the local reality become a space of flux and connection between cultures — and global is the cultural perspective in which this exhibition places the local dimension. The spatial-temporal compression of global online communications has brought a multitude of artists to the natural temporal dimension of ceramics: the lengthy drying and firing times mark a slowing down of time, almost tantamount to a suspension of time.

This exhibition is presents works in ceramics which have been made in an attempt, on the part of the artists, to make whatever they wanted and whatever, in the final analysis, it was possible to make. As the works were being produced, so the project developed, this exhibition being the end result.

The mobility of the participating artists, from Italy, Korea, Argentina, Kossovo, France, Denmark, Japan, Serbia, Spain, Iran, Austria, Cameroon, China, Switzerland, England, Ghana, Sweden and America towards the tiny dot on the map which is Albisola is what has made this project possible. And it is the journey undertaken by all these artists to Albisola, as well as the hospitality shown by the local manufacturers — hospitality as a disinterested and desirous gift — that has made for an opening onto the ‘other’. Both the hospitality of the manufacturers and the willingness of the various artists to come here are the underpinning factors of a mutual opening-up. Both the hosts (the local manufacturers) and the guests (the artists) feel the need to address culture, tradition and each others’ rituals, while migration and hospitality both entail the assertion of each individual’s

identity as well as its transformation.

The exhibition has spawned a community in the formation phase, temporary, fluctuating, the unpredictable identity of which is either confirmed or modified by every last participating artist. One is tempted to define them as a community of passion that has brought together the protagonists for the duration of this project in Albisola and which has given form to an exhibition that is the fruit of the mobility of the artists and the hospitality of the local craftspeople. Without this, the whole exhibition would not have been possible.

The various protagonists from the new extraterritorial and multicultural global art scene who have temporarily descended upon Albisola find themselves in a position whereby they have to filter their own identities through the possibilities and the limitations of an ancient medium (ceramics), all the while throwing themselves into a process of affirmation and translation of their own cultural singularity. In turn, the local area is welcoming hitherto unseen contributions which sees the material worked in a key of metamorphosis. The final effect is that each and every component is transformed and enriched, the transforming reciprocity a founding factor in the manufacture of these works.

Albisola brings us tradition. Here, expertise is handed down across the generations through the workshops, while the reality is characterized not only by the continuity of the manufacturing tissue but also by a certain discontinuity which comes about when the industry opens itself up to new models which, over the centuries, have been taken on board from outside and reworked. However, looking at this age-old tradition, we should not think in terms of a closed and crystallized productive network. This centuries-old, kleptomaniac tradition would soon be struck by the experimental discontinuity that came with the modern age, as represented by the artistic avantgardes of the twentieth century. And while local ceramics production over the ages had had its fair share of discontinuity as a minor decorative and utilitarian production, the avantgarde artists would ensure that it was catapulted once and for all from that realm.

The radical critique of society founded on work and the accumulation of capital wealth as promoted by the artists of the 1950s would eventually filter through into the ceramics factories of Albisola. This was during a time when figures from the world of avantgarde art were coming into these traditional manufacturing plants and subjecting them to radical critique. Asger Jorn’s principle of anti-economical creation, which lies at the very root of the Situationists’ theory of the individual’s liberation from work, would also be put into practice in Albisola. Counterpoised with the economic rationalization of every aspect of individual life behind the dominant capitalist ideology, the last avantgardes of the twentieth century would lead ceramics into non-productivity. When the avantgarde artist enters into the factory, the production cycle is suspended as he endeavors to create the deformed and the senseless. Of primary importance here is the artist’s joy at placing the factory at the service of the uselessness of modern art and its formal dissolution. And it is incredible to witness the freeing of ceramics from its minority status, from its confinement within what is commonly referred to as applied arts, something which would be definitively achieved during the 1950s, coinciding as it did with the programmatic formal disaster of the ‘major’ arts.

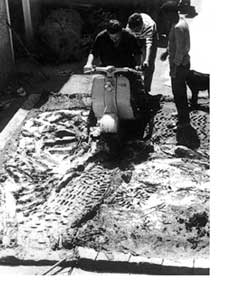

The formal disaster of modern art coupled with the anti-economical logic of the suspension of productive work in the factories has produced some exemplary output. See, for example, the extraordinary monumental panel in ceramic created by Asger Jorn in 1959 at the Fabbrica San Giorgio by riding over the unset surface with a Lambretta, a prime example of positive destructiveness which calls upon the very Luddite and vandalistic spirit which, to quote Guy Debord, “belonged more to the Situationists than to anyone else”, not to mention the 2nd Festival of Ceramics, organized by Jorn at Albisola, which would feature an exhibition of hundreds of plates designed not by professional artists but by children: this was 1955, and we would have to wait until the late 1960s for Georges Maciunas’s statement, “Everything is art”, and Josephy Beuys’s “Every man is an artist”. Meanwhile, even Jorn’s house in the Albisola hills would seem to adhere to the radical critique of ceramics, art and society in so far as it is a blueprint of a collective work. Created with his neighbor Berto Gambetta, a great part of the project is given over to the salvage of fragments and scraps of ceramics which have already over-spilled from the production cycle.

Our project for Albisola springs from a cultural legacy made up of the centuries-old productive tissue of local ceramics manufacture and its overthrow in the formal disaster of modern art, as realized in exemplary fashion by one of the great protagonists of the twentieth century artistic avantgarde.

The ashes of avantgarde art and local tradition are, therefore, the cultural capital and habitat in which the current multicultural horizon of art marries the zero degree that ceramics was brought to in the twentieth century with the centuries-old rules of the craft and the virtuouso power of skilled craftspeople.

By bringing together modernity and tradition in the common language of ceramics (a sort of Esperanto), this exhibition is not only embracing but generating a communion and exploitation of particularism and otherness, a confirmation of the paradoxical statement by Pasolini whereby “only revolution can save tradition”.

Roberto Costantino

2001