The term is borrowed from Aimé Césaire, who, in Discourse On Colonialism, (1950), wrote: “The fact is that the so-called European civilization – ‘Western’ civilization – as it has been shaped by two centuries of bourgeois rule, is incapable of solving the two major problems to which its existence has given rise; that Europe is unable to justify itself either before the bar of ‘reason’ or before the bar of ‘conscience’; and that, increasingly, it takes refuge in a hypocrisy which is all the more odious because it is less and less likely to deceive. Europe is indefensible.” Trans. Joan Pinkham (NY: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 31-32.

Ibid, 36.

Ibid, 36.

Ibid, 37.

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (London: Pluto Press, 1986), 230.

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (NY: Grove Weidenfeld, 1963), 311.

Ibid, 315.

Ibid, 316.

On Albert Laprade, see: Albert Laprade, Les carnets d’architecture d’Albert Laprade (Paris: Kubik Editions, 2008); Maurice Culot & Anne Lambrichs, Albert Laprade (1883-1978) (Paris: Editions Norma, 2007); Anne Demeurisse, ed., Alfred-Auguste Janniot (1889-1969), (Paris: Editions Somogy, 2003). On the building, see: Hélène Bocard, Le palais de la Porte Dorée (Paris : Editions du Patrimoine, Collection(s) : Itinéraires du patrimoine, 2018); Maureen Murphy, Un Palais pour une Cité. Du musée des colonies à la Cité de l’histoire de l’immigration (Paris: RMN-CNHI, 2007); and Germain Viatte, ed., Le Palais des colonies, Histoire du Musée des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie (Paris: Editions RMN, 2002). On the bas-relief, see: Georges Petit, "La faune exotique dans les bas-reliefs du musée des Colonies", La Terre et la vie. Revue d’histoire naturelle, 1. (February, 1931). On the colonial exhibitions, see: Charles-Robert Ageron, "L’exposition coloniale de 1931 : mythe républicain ou mythe impérial", in Pierre Nora, ed., Les Lieux de mémoires, 1, La République (Paris: Gallimard, 1984); Catherine Hodeir & Michel Pierre, L’Exposition coloniale de 1931 (Brussels: Complexe, 1991).

National Immigration History Museum website and Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, ed., Guide du Patrimoine Paris (Paris: Hachette, 1994).

Cited by Gilles Manceron, Marianne et les colonies. Une introduction à l’histoire coloniale de la France (Paris: La Découverte, 2003), 153.

Cited by Charles-Robert Ageron, "Les colonies devant l'opinion publique française (1919-1939)," Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, tome 77, 286. (1er trimestre 1990), 51.

Clair Maingon, "Le palais de la Porte-Dorée, témoignage de l’histoire coloniale", Histoire par l'image (April 2008), https://histoire-image.org/etudes/palais-porte-doree-temoignage-histoire-coloniale; Steve Ungar, "La France impériale exposée en 1931 : une apothéose", Sandrine Lemaire, ed., Culture coloniale 1871-1931. (Paris : Autrement, 2003), 201-211; Raoul Girardet, "L'apothéose de la ‘plus grande France’: l'idée coloniale devant l'opinion française (1930-1935)", Revue française de science politique, 18ᵉ année, 6. (1968), 1085-1114.

See: Roland Pourtier, "Les chemins de fer en Afrique subsaharienne, entre passé révolu et recompositions incertaines", Belgeo, 2. (2007), 189-202; Owona Adalbert. "A l'aube du nationalisme camerounais : la curieuse figure de Vincent Ganty", Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, tome 56, 204. (3e trimestre, 1969), 199-235.

On postcoloniality, see notably: Thomas Brisson, "Les ‘études subalternes’ indiennes et le ‘tournant saidien’", Brisson, ed., Décentrer l'Occident. Les intellectuels postcoloniaux chinois, indiens et arabes, et la critique de la modernité (Paris: La Découverte, 2018) 215-271; Neil Lazarus, ed., Penser le postcolonial : une introduction critique (Paris: Editions Amsterdam, 2006); Capucine Boidin, "Études décoloniales et postcoloniales dans les débats français", Cahiers des Amériques latines, 62. (2009), 129-140; Mamadou Diouf, L’historiographie indienne en débat, colonialisme, nationalisme et sociétés postcoloniales (Paris: Karthala, 1999); Achille Mbembe, De la postcolonie. Essai sur l’imagination politique dans l’Afrique contemporaine (Paris: Karthala, 2000); Mbembe, "Postcolonial et politique de l’histoire", Multitudes, 26. (Sept. 2006); Jim Cohen, Elsa Dorlin, Dimitri Nicolaïdis, Malika Rahal & Patrick Simon, eds., "Qui a peur du postcolonial?", Mouvements, 51. (Sept.-Oct. 2007); Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” Wedge, 1985.

There are many publications on anticolonial struggles, and increasingly so. It is impossible to do them justice without citing them all.

See, among others: the indispensable Amzat Boukari-Yabara, Africa Unite ! Une histoire du panafricanisme (Paris: La Découverte, 2014); the useful reference, despite its oversights, Philippe Dewitte, Les mouvements nègres en France, 1919-1939 (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1985); François Manchuelle, "Le rôle des Antillais dans l'apparition du nationalisme culturel en Afrique noire francophone", Cahiers d'études africaines, vol. 32, 127. (1992), 375-408; Fredrik Petersson, "La Ligue anti-impérialiste : un espace transnational restreint, 1927-1937", monde(s). (Nov., 2016), 129-150. See also: in Histoire générale de l’Afrique VII, UNESCO (2000): M’Baye Gueye & Albert Adu Boahen, "Initiatives et résistances africaines en Afrique occidentales de 1880 à 1914", 137-170; Walter Rodney, "L’économie coloniale", pp. 361-380; Albert Adu Boahen, "La politique et le nationalisme en Afrique occidentale, 1915-1935", 669.

The Kanak leader Ataï was decapitated, and his head sent to Natural History Museum in Paris in the aim of confirming the inferiority of the Kanaks, then was forgotten in the museum’s reserves. In the twentieth century, the Kanak people requested that Ataï’s skull be returned. After long negotiations with the French State and the museum, which could not “find” the skull, Ataï was finally returned to his people in 2014. A very powerful vast ceremony of return was celebrated in his honor.

Fatou Sarr, “Féminismes en Afrique occidentale ? Prise de conscience et luttes politiques et sociales", Vents d'Est, vents d'Ouest : Mouvements de femmes et féminismes anticoloniaux (Graduate Institute Publications, 2009). See also: Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, "Femmes et politique : résistance et action en Afrique de l’Ouest", in Coquery-Vidrovitch, Les Africaines. Histoire des femmes d'Afrique subsaharienne du XIXe au XXe siècle (Paris: La Découverte, 2013), 253-288. Also see: Cheikh-Anta Diop, Nations nègres et culture (Paris: Présence africaine, 2000); Joseph Ki Zerbo, Histoire de l’Afrique noire (Paris: Hatier, 1994); Histoire générale de l’Afrique, volume 1, Afrique & histoire, "L'anticolonialisme (cinquante ans après). Autour du Livre noir du colonialisme" (Paris: UNESCO, 2003), 245-267. Then see: Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, "L'Afrique coloniale française et la crise de 1930 : crise structurelle et genèse du Rapport d'ensemble", Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, tome 63, 232-233. (3e et 4e trimestres, 1976); Coquery-Vidrovitch, ed., L'Afrique et la crise de 1930 (1924-1938), 386-424; Didier Monciaud, "Rebelles contre l’ordre colonial : expériences et trajectoires historiques de résistances anticoloniales", Cahiers d’histoire. Revue d’histoire critique, 126. (2015), 13-18; Alain Gresh, "Révoltes prémonitoires dans les colonies", Le Monde diplomatique. (Sept. 2014), 46-47; Bernard Lanne. "Résistances et mouvements anticoloniaux au Tchad (1914-1940)", Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, tome 80, 300. (3e trimestre, 1993), 425-442.

Pierre-Frédéric Charpentier, "Imbéciles, c’est pour vous que je meurs". Valentin Feldman (1909-1942) (Paris: CNRS Editions, 2021), 87 & 88.

Cited by Raoul Girardet, "L'apothéose de la ‘plus grande France’ : l'idée coloniale devant l'opinion française (1930-1935)", Revue française de science politique, 6. (1968), 1085-1114. Also see: Charles-Robert Ageron, "Les colonies devant l'opinion publique française (1919-1939)", Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, tome 77, 286. (1st trimester, 1990), 31-73. The author fittingly describes the huge propaganda effort that the government undertook, with the help of learned societies and the media, to popularize the colonial empire among the French.

On July 4, 1931, L’Humanité announced a counter-exhibition. Entitled La vérité sur les colonies (The Truth About the Colonies), it was organized by the League against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression and was set up in a large, two-story wooden construction with vast bay windows on a piece of land belonging to the CGTU (United General Confederation of Labor), Place du Colonel Fabien in Paris. See: Alain Ruscio, "Contre l’Exposition coloniale de 1931 (Paris-Vincennes) : des voix fermes, mais bien isolées. Aperçus", Aden, vol. 8, 1. (2009), 104-111; Vincent Bollenot, "‘Ne visitez pas l'exposition coloniale!’ La campagne contre l'exposition coloniale internationale de 1931, un moment anti-impérialiste", French Colonial History, 18. (2019), 69-100.

A lot of works exist concerning the decolonization of the museum, starting with its very possibility.

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, (London & NY: Verso, 1983), chapter 10. Studies of the museum as a structural element of nationalism and colonialism have multiplied these past decades, testifying to the importance of this institution in the invention of a tradition, the Eurocentric presentation of the world, and civilizing racism. It is difficult to choose from this abundant bibliography, but mention must undoubtedly be made of the seminal work by Edward Said, Orientalism. Western Conceptions of the Orient (London: Routledge, 1978). In recent years, museums have begun revising their museography and labels, but in the eyes of researchers, artists, and decolonial activists, this revision has not radically challenged structures. See, for example: Fisun Güner, “Why Decolonizing Museums Is Not Enough”, Elephant Magazine (10 December 2020), ➝, or Arwa Aburawa’s film The Museum Will Not Be Decolonized (2019), ➝.

A specialist of monumental stone décors, a prolific sculptor of numerous public commissions, Alfred-Auguste Janniot marked the history of Art Déco. He also realized the bas-reliefs of the Rockefeller Center in New York in 1934, those of the Bordeaux Labor Exchange in 1936, two of the major bas-reliefs on the back of the Palais de Tokyo in Paris for the 1937 Universal Exhibition, and the high reliefs of the Mont-Valérien Memorial in 1956. Claire Maingon, Alfred Janniot (1889-1969) : à la gloire de Nice (Paris: Galerie, Michel Giraud, 2007); Anne Demeurisse, ed., Alfred Auguste Janniot - 1889-1969 (Paris: Éditions d'Art Somogy, 2003).

On botany’s role in colonization, see: Lucile H. Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion. The Role of the British Royal Botanic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); Londa L. Schiebinger, Plants and Empires: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2009); and the book that demonstrates the consequences of pillaging, Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London/NY: Verso, 2018).

Gallieni’s statue stands in Place Vauban in Paris, behind the École Militaire army training facilities. This square and the nearby Place Denys host quite a collection of Marshals – Gallieni, Lyautey, Fayolle – plus one General, Mangin. This is yet another site in Paris that assembles several elements of France’s colonial, racial, and gendered history.

On November 21, 2020, French police beat up the music producer Michel Zecler because he was Black. He was given 180 days’ temporary incapacity to work, “due to the physical repercussions, and the psychological impact signaled by his doctors.” Thanks to videos filmed by neighbors, this beating was made public, and the truth re-established, as, after taking him into custody, the police intended to accuse Zecler of assaulting a police officer.

Translated from the French by Melissa Thackway.

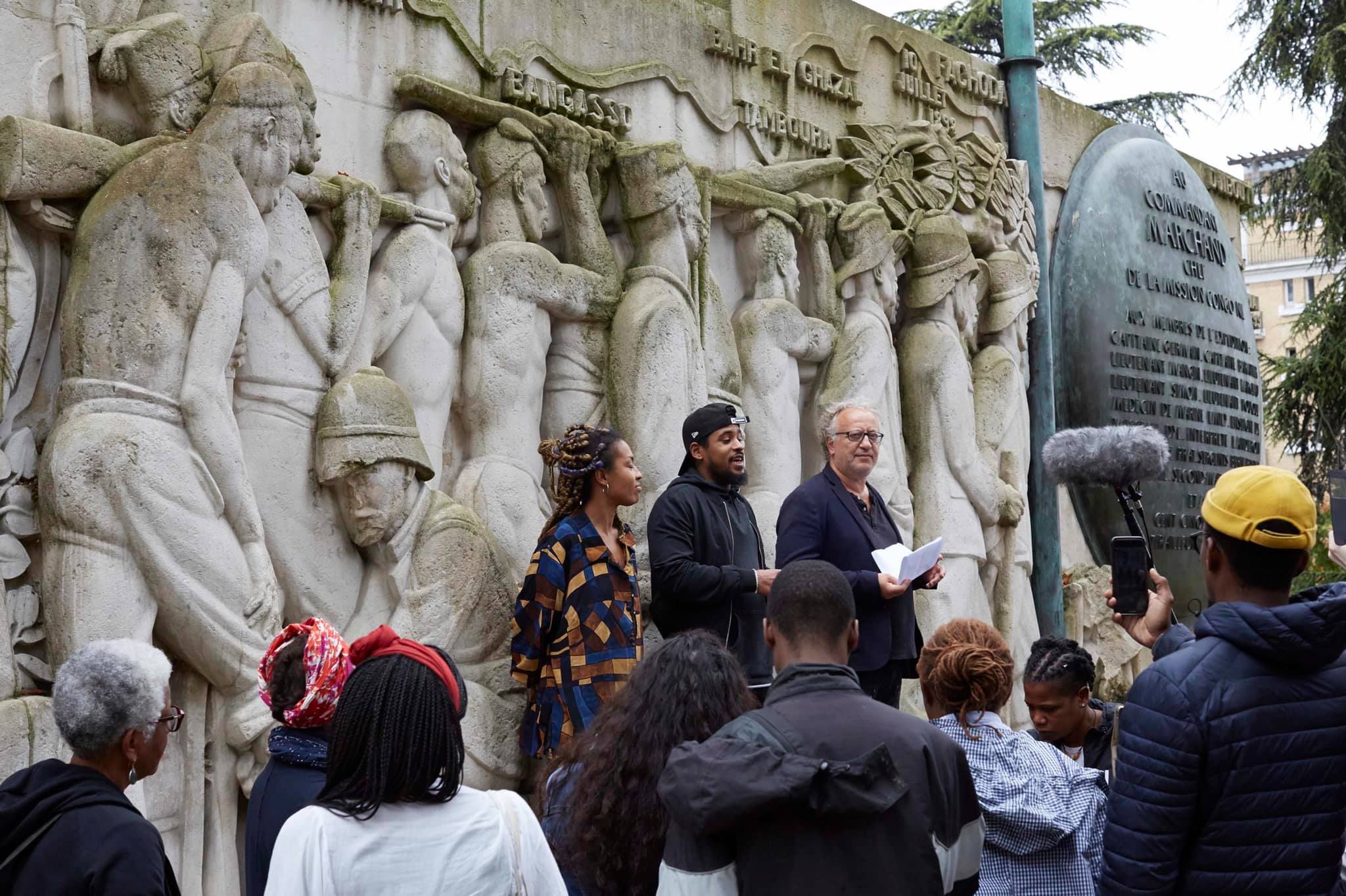

Originally published as part of the book De la violence coloniale dans l’espace public: Visite du triangle de la Porte Dorée (Of Colonial Violence in Public Space: A visit to the Porte Dorée Triangle) (Shed Publishing, 2021).