Suzanne Moon, “Takeoff or self-sufficiency? Ideologies of development in Indonesia, 1957-1961,” Technology and Culture 39, no. 2 (1998): 187º212; Eunike Gloria Setiadarma, “Cultivating Pembangunan: Rice and the Intellectual History of Agricultural Development in Indonesia, 1945-65,” (2019), ➝.

Since 2015, both ministries have merged to form the Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

Rini Astuti and Andrew McGregor, “Responding to the green economy: how REDD+ and the One Map Initiative are transforming forest governance in Indonesia,” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 12 (2015): 2273–2293; Nabiha Shahib, “Indonesia: one map policy.” Open Government Partnership (2016).

It has been argued that this restructure enabled district mayors and village leaders, backed by political elites in the Ministry of Forestry, to finance their budgets by faking or fixing permits for resource companies. See Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton University Press, 2005); Tania Murray Li, The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics (Duke University Press, 2007); Nancy Lee Peluso, “Whose woods are these? Counter‐mapping forest territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia,” Antipode 27, no. 4 (1995): 383–406.

Rini Yuni Astuti, REDD+ Governmentality: Governing Forest, Land, and Forest Peoples in Indonesia, Victoria University of Wellington, PhD Dissertation (2016).

Ibid.

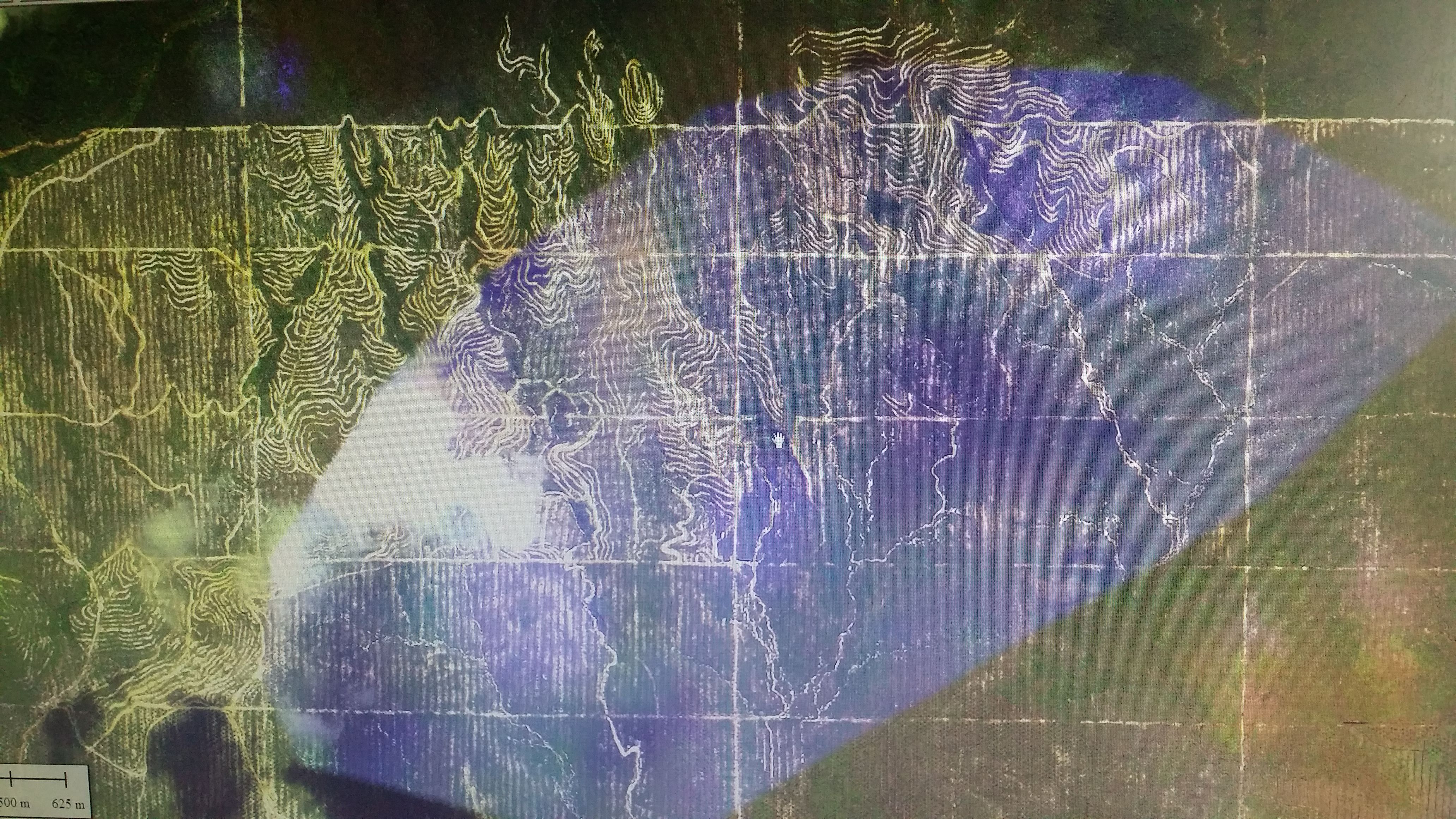

A base map is a layer with geographic information that serves as a background setting for other maps. It establishes the geometrical and orientation reference for the viewer of a thematic map.

Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power (Macmillan, 1984: 290); Michael Taussig. Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative (Stanford University Press, 1999).

Raminder Kaur and William Mazzarella, eds., Censorship in South Asia: Cultural regulation from sedition to seduction (Indiana University Press, 2009).

Eva Hayward, “Fingeryeyes: impressions of cup corals,” Cultural Anthropology 25, no. 4 (2010): 582.

Sophie Chao, “There Are No Straight Lines in Nature: Making Living Maps in West Papua,” Anthropology Now 9, no. 1 (2017): 16–33; Jennifer Fisher, “Relational Sense: Towards a Haptic Aesthetics,” Parachute: Contemporary Arts Magazine 1 (1997); Andrea Ballestero. “Touching with Light, or, How Texture Recasts the Sensing of Underground Water,” Science, Technology, & Human Values 44, no. 5 (2019): 762–785.

Bayu discussed with me how he trained his FCN model and developed a ground truth image: First, superimpose a 1 by 1-meter pixel grid on to a LiDAR point cloud. The grid is meant to represent a pixel-based image. There will likely be more than one LiDAR point within a pixel. Second, in each pixel of the grid, choose the LiDAR point with the lowest value. Each LiDAR point contains a value calculated from (1) elevation; (2) intensity; (3) return number; and (4) height difference i.e. the difference in elevation between a LiDAR point and neighboring points. It is assumed that LiDAR points with higher values will represent non-ground features such as vegetation and building. Third, tag the pixels containing low values as ground. Points that exceed the threshold of 15cm are labeled as non-ground points. The final tagged image is called the ground truth image. Fourth, create the training dataset using an unlabeled image extracted from LiDAR point cloud (from steps 1 and 2). Fifth, train a fully convolutional network (FCN) with dataset. Sixth, the output of the FCN is a predicted label for each pixel. Seventh, compare the output to the ground truth image. If the predicted labels (“ground” and “non-ground”) are different from the ground truth image, change the weights and parameters in the FCN model until the output’s labels correspond to the ground truth image. Eighth, transfer the predicted label of each pixel back to the original LiDAR point cloud. Ninth, repeat steps two and three to create an image of non-ground points derived from selecting the highest values. Separate non-ground points into finer classes: vegetation and building. Building and vegetation labels are created based on three assumptions: (1) A building’s roof surface is comprised of LiDAR points with similar elevation values; (2) A building’s edges do not have neighboring points on all of its sides; (3) the intensity value of vegetation is lower than that of buildings. Building and vegetation labels are transferred to non-ground points from the result of the ground classification derived in step three.

Louise Amoore, “Doubt and the Algorithm: On the Partial Accounts of Machine Learning,” Theory, Culture & Society 36, no. 6 (2019): 147–169.

Xiangyun Hu and Yi Yuan, “Deep-learning-based classification for DTM extraction from ALS point cloud,” Remote Sensing 8, no. 9 (2016): 730.

Dan McQuillan. “Data Science as Machinic Neoplatonism,” Philosophy & Technology 31, no. 2 (2018): 253–272.

Ibid, 261.

Os Keyes. “The Gardener’s Vision of Data,” Real Life, May 6, 2019, ➝.

Mitali Thakor, “Digital Apprehensions: Policing, Child Pornography, and the Algorithmic Management of Innocence,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 4, no. 1 (2018): 8.

Helena Varkkey, “Patronage Politics as a Driver of Economic Regionalization: The Indonesian oil palm sector and transboundary haze,” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 53, no. 3 (2012): 314–329.

Work on “inescapable visibility” and “hypervisibility” comes from a long tradition of Black feminist scholarship on the representation of Black lives, visibility politics, and surveillance. See for instance, important work written by scholars Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Duke University Press, 2015); Nicole R. Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness (University of Chicago Press, 2011); Hortense J. Spillers, “Mama’s baby, papa’s maybe: An American grammar book,” diacritics 17, no. 2 (1987): 65-81; Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Crossing Press, 2012 {1984}).

Juno Salazar Parreñas, Decolonizing Extinction: The Work of Care in Orangutan Rehabilitation. (Duke University Press, 2018).

Ibid, 68–71, 121.

This essay documents field research conducted between 2016 to 2018 in Indonesia. The author would like to thank Lisa Nakamura, Juno Salazar Parreñas, Sareeta Amrute, Silvia Lindtner, and Andrew Moon for their careful reading, generous support, and wit. This piece has been many years in the making since it was first presented for a panel on Platform Practices and Predictive Seeing organized by Adrian Mackenzie and Anna Munster at 2018 annual meeting of the Society for Social Studies of Science (4S) and subsequently, for a panel on Artifice Intelligence: Fabrication, Fakery, and the Virtually Human organized by Beth Semel and Mitali Thakor at the Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association in 2018. The author would also like to thank Adrian Mackenzie, Beth Semel, and Mitali Thakor for their very helpful feedback during these panels and outside of them. Finally, this piece wouldn’t have been possible without the data technicians and scientists who kindly shared their drawings, surveys, and musing.

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.