On June 26, 2029, the Director launched the new moon. It was named Ruda, after the ancient pre-Islamic lunar deity. It made the bioluminescent coastline—seeded with the appropriate algae just a few years ago—ripple a ghostly lilac instead of the usual blue. The idea was that Ruda would appear on the horizon at precisely the moment that the old moon entered total eclipse, during what would be the largest lunar eclipse of the twenty-first century. But under the benevolent glow of Ruda, there would never be darkness again.

Nobody could forget the total solar eclipse three summers ago, on the day that the Kushner accords were signed. Its path of totality moved in an unerringly straight line, from the Ash-Sharmah resorts at the very tip of the headland where the Gulf of Aqaba met the Red Sea all the way to Tabuk, on the far edge of the megacity. There were nervous murmurs among the older locals, the ones who tilled the roses, or gülfields. What was left of them anyway, after most of the community was resettled to the Ash-Sharat highlands in anticipation of the summit that would create a new TransJordanian state. These days, they mostly supported the population of the megacity, or worked at Halat al Ammar on the former Jordanian border, now home to the Dumah military superbase.

Eight minutes after Ruda was launched, the moon burnt saffron, then sickly vermillion. Like a bloody burnt jalebi, my stomach grumbled. My bunkmate Sabzal was transfixed, and spent the next few months singing Urdu ghazals about the moon. You wouldn’t expect that voice coming out of a man like that, built like that asparagus-looking guy on the ration cans. He never did the catchy numbers, only those bleak tanhaai ones. Years later, when he returned to Quetta, he wrote to tell me that they had named their firstborn daughter Mahbano after the moon that night.

That blood moon changed the roses forever. Historically, the world’s best rose attar was produced over a million meters away in Ta’if, in Western Saudi Arabia. The rare Ward Taifi is thirty-petaled and related to the Damask rose, but with a much more intense fragrance. Powdery-soft, faintly tannic, bubblegum or gulabi pink, beguiling. Some believe it is a child of the Ottoman empire—and it’s true, it’s almost indistinguishable from the famous Bulgarian Kazanlik strain, at least until you smell it. In the agriluxe community of Al Huda Tranquility Resort & Spa by Anantara, it is rumored to have originated in India. Specifically, with one Baba Budan, the sixteenth-century Sufi who famously exchanged seeds of the Kannauj rose so beloved by the Mughals for seven coffee beans, which he then smuggled home, breaking the two-hundred-year Mocha monopoly.

The Tabuk Heritage Area may have once been known as Tabuk of the Roses, but its flowers weren’t anything you’d want to balikbayan home. That was, until the 2029 lunar eclipse at least, the night that Ruda rose. The next morning, the hillsides of Al Huda and Ash Shafa, the two major Taifi rose-growing areas, were bleached. The flowers were bone white and, moreover, had no smell. As for those formerly anemic Tabuki roses? They gained an intoxicating earthy-floral perfume, somewhere between chanterelles (Shaanti-rell, Sabzi would always say) and kewra. Slowly, as if they had an internal sepsis, their petals turned a deep, rusty, burnt red. New blooms grew with only five petals, like the wild roses of old. MBC ran a massive Shakespeare LARP, and the winner got to rename the flowers. They settled on Mahgul, or Moon Rose. I know you’re thinking but that’s an Iranian name, but remember, this was back in 2029, long before the third Gulf War.

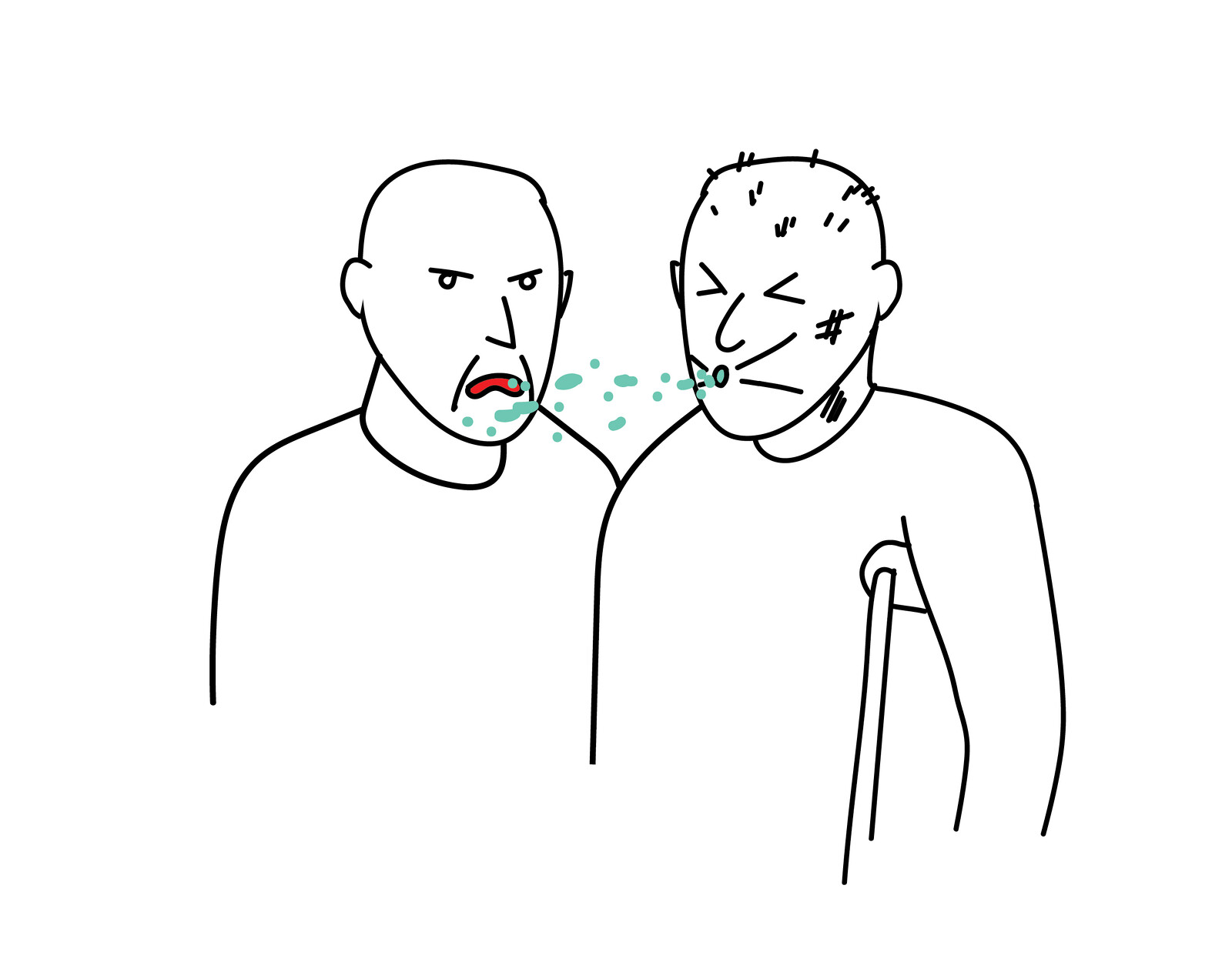

The five major Taifi attar houses blamed the Tabukis; the Tabukis blamed nobody and quietly savored their good fortune. Jedawwi wits dubbed the protracted legal battles and the painfully slow, alopecic thinning that ensued the Ward of the Roses. Some blamed the cloud-seeded rains that had been scheduled the past week to wash the ground before the launch of Ruda; harsh words with their edges filed off by the soft Hejazi dialect. Those jostling for political power said nothing, but rumors circulated about the desert ionizers, recently perfected by TurkSom and installed to maintain a cool, even climate for the roses and the ruddy-faced tourists.

Others openly blamed the Dutch, because it was unnatural to be SLS printing new islands out in the sea, like a worldbuilder stuck on reticulating splines. Just because The World bubbled under was no reason to leave tried and tested tradtech like dredging behind. Also, Egypt was already claiming the new islands. “Saudi Arabia will own all land in the Straits of Tiran, in all media now known or hereafter devised,” it was written in the Causeway agreement. Everybody understood that it extended to the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea too. Besides, it was always safest to accuse the Europeans. Everybody knows you can’t trust them; just look at what happened with the Dammam mangroves. Nobody bothered mentioning the Calyxt-#emite Sciences crops that had turned Rub3 al Khali into the breadbasket of the META region. Nobody dared even think, even in the quietest parts of their minds, about what it meant to raise a moon named after a lunar deity who hadn’t been worshipped in the area for over a thousand years. You never knew who was listening to your thoughts.

Years passed. How many, it doesn’t matter; it’s safer not to say. The double Ramadan of 2030 came and went. That was a hard year. So too did several solar and lunar eclipses. We held our breaths each time I tell you, and Venus transited Uranus not once but twice. Atarsamain walks, our local brothers said by way of greeting every morning afterwards; Nuha rides, we would reply dutifully, not quite understanding what it meant. They didn’t give us cultural training, those of us in Service and Spine, but you picked up a bit of the local lingo all the same. The residents of the City, the Modified Million, came to depend on those moon roses. The export supply dried up. No matter the price—a single vial of Mahgul sold on the Belt and Road could set you up for life and your next seven reincarnations too—inside the megacity, only Residents had access to the attar.

It was said that Tabuki attar ran through Resident veins like the ichor of dragons. That they weren’t of human origin at all. That every morning after Fajr or Karadarshana or Shacharit or other dawn prayers (the non-practicing wrote their Five Morning Pages), Residents plugged into the Spine. They received their daily dose of attar while a dialysis-like machine cycled out the spent oils. It was said that any Resident who didn’t have a system full of converted attar by Rudarise died a mysterious, but mercifully swift death. Nobody knew what happened to the bodies, but myths swirled around about transference and a secret weapon being built, deep in the Hejaz mountains. Ruda slowly grew brighter until a night of the full moon was almost as bright as daylight, suffusing the Resident cities with a wash of lavender.

What were the Resident estates like? Well you must have seen the vids: it was like that, but more tranquil, more beautiful, life as it was meant to be. Above ground, at least. Most of us megacity paavams lived simple, ordinary lives, no different from the ones our ancestors lived in the 1970s, the 1990s, the 2020s, and every decade in between when we travelled over the Red and Arabian seas, to find work, to send money home, to visit only every three years, and return when our contracts expired, either by plane or by body bag. Those of us who worked inside the City did get rotated out to Za3farana on the Suez coast every six months—as if anyone could relax with all those noisy wind farms—as well as monthly blood tests—something to do with exposure. I knew it was probably poisoning me, but at least they knew how to hold back the rising sea here.

Za3farana is where I first met N. I can’t tell you his full name, it’s too risky. We got chatting at the bar of the old Fanar de Luna resort after he noticed my Udaya Suriyan rising sun pendant. I usually kept it tucked in my shirt, but the ACs were broken that week and I had the top few buttons open. He told me about Akhenaten, this Egyptian Pharaoh who tried to start his own sun-worshipping religion, and the ruins of his city at Amarna. I didn’t have the heart to tell him my sister-in-law gave it to me, that I wasn’t into nationalism or revolution, that I was just another expat mercenary, that I wasn’t even Tamil. When the endless brunch-drink-tan R&R cycle grew old, N and I would meet up at those little baladi bars up and down the coast where all the resort workers would go to forget the day’s indignations. Later, I would realize that many of them displayed faded silken banners with the same imagery: an ankh with a rose at its center, surrounded by radiating lines.

We’d talk about our childhoods, what it was like to grow up in these dead-end coastal towns with only classic rock for an escape. I learned about the pharaonic religion of Atenism, about the sun god Ra and the moon god Thoth, the snake god Apep and the eternal struggle between one black hole and the next, when the world was destroyed and born anew. About Atenism’s roots in a much older cattle cult—the ones who left all those mysterious rectangular musatils all over the northwestern region—that dates back some 8,000 years to when the peninsula was monsoon-lashed and lushly verdant.1 As the sun wound down, and the strains of those ubiquitous Bahraini Bob Marley cover bands began to carry on the breeze, we’d split a bowl and listen to The Doors. Sometimes his friends would come too. Jolly S, garrulous R, L was kind of an asshole, frankly, and shy, circumspect T.

One of those nights when the gupshup and the Sakaras were free-flowing, we just kept going. They told me about the Ateniyun, a sort of neo-Atenite solar cult. Unlike the Ottoman era neo-Atenist revival, with its fervent anti-imperialist nationalism and social redistribution imperative, they frankly sounded like a punchline about sun saluting backpackers on the qat trail. Besides, even as the Ateniyun freely helped themselves to Atenist doctrine and aesthetics, their theological roots were actually in an eighteenth-century mystical movement, the Rosicrucae, which was brought here by the Europeans who set up hotels along the strip—as if they knew about oil, about Nasser, about the megacity. Sounds like they could predict the future, I joked. And then—I’ll never forget this moment—N got serious, leaned forward, and said in French, “Le futur n’a pas d’avenir.”

When the Third Gulf War happened, they sent us to Duba instead, which had somehow managed to remain a backwater despite all the development around it. I never saw N or any of the others again, but that conversation had broken a seal. Over the next few months, letters started to materialize; the vintage kind, written not on paper but papyrus that crumbled if you looked at them too hard. Not by postal drone but in my room, placed on the bed or desk. It had to be the woman who came to clean my room, but when I tried to ask her, she stared and made a hand sign I didn’t recognize. I didn’t want to push or ask her supervisor—you heard stories. The thumb was held horizontally, the index finger curved, and the other fingers pointing straight down. It felt a little unnatural, and I don’t know why, but I practiced until I could do it easily, just as I had taught myself to make the Vulcan sign all those years ago.

The letters were innocuous at first. Each packet was sealed with wax, stamped with a familiar symbol that looked like a rose blooming from an ankh. Each missive was signed by a different Arabic coronal consonant—those sun-obsessed Ateniyun couldn’t resist, could they—ت، ث، د، ذ، ر، ز، س، ش، ص، ض، ط، ظ، ل، ن, and when they reached the end of this cycle, it began again. The ink didn’t seem to fade, even when I left a stack in front of a window once. I came to think of them as the sun letters. They contained printouts of new scientific literature, news stories, ecocritical writing about the environmental impact of the megacity, and bits of solar mythology from around the world. Writings from Aleister Crowley, terrible solar sphincter fiction from Georges Bataille, alchemical texts and general esoterica. Once, in a hand-sewn book where the last pages had been torn out, was a story from the thirteenth century astronomer-doctor Zakariya Al Qaswini about an alien who lands and is both fascinated and bemused by the local culture. I wondered if it was true, and aliens had just hung around in mountainous caves, biding their time. I didn’t even know for sure that it was related to N and co, but at the same time, I knew.

Many years passed, but the dispatches continued. I got promoted, then promoted again, not through any great show of competence but simply by having stuck it out for longer than most. I was moved to one of those satellite communities just west of Tabuk, in prime mahgul territory, and moved up in the world, quite literally. I was given a small apartment on the pedestrian layer, above ground for the first time. But I wasn’t a Resident. They were careful to always maintain the distinctions between us. You didn’t need to be told; you knew your place, and there was no point developing one of those belonging complexes that my cousin and all those Gulfy kids had. Still, it was nice to be up there, to be allowed to stroll in the manicured little drought-resistant gardens and live, for the first time in my decades here, a car, grime, and pollution-free existence. I made new friends; I even started seeing someone from the megacity, before they were transferred away to consult on the rebuilding of East Turkestan. Life was good.

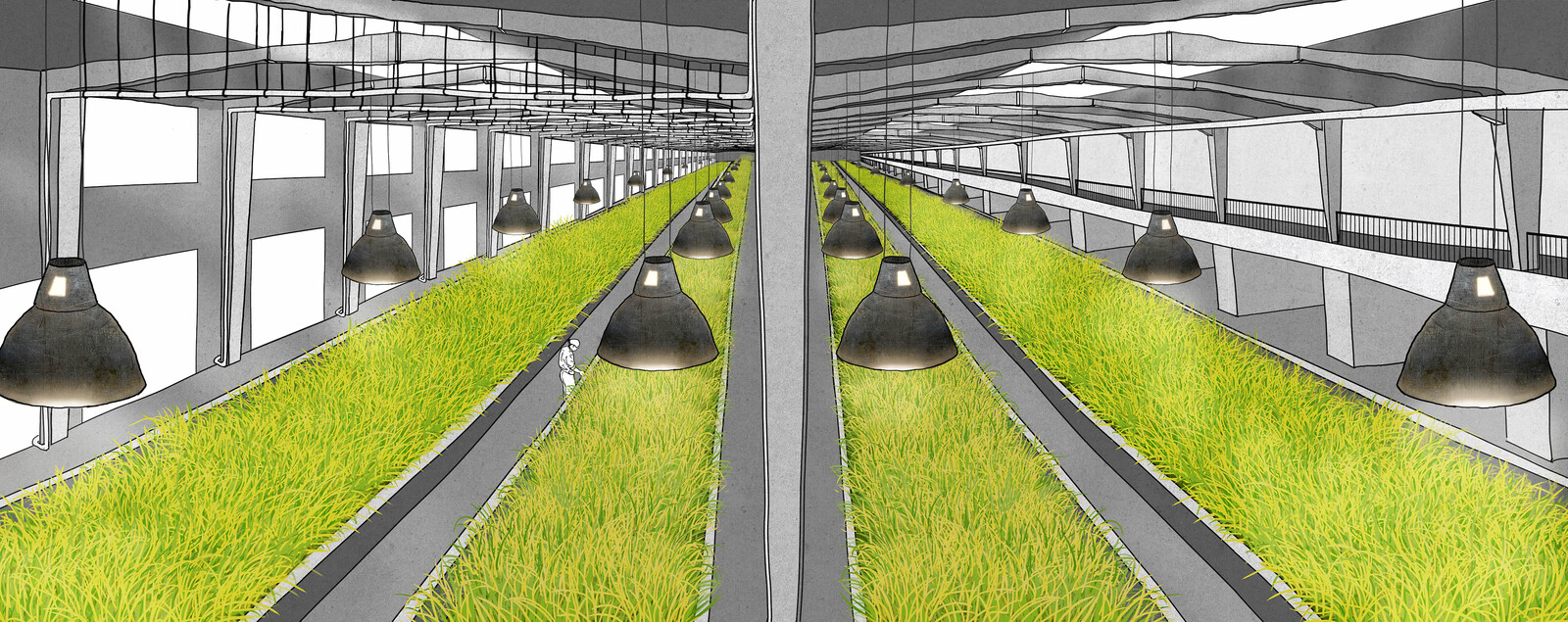

Outside the megacity, things weren’t so easy. At first, genmodding agriculture paid off in a big way, and there were more crops than an Amreeki MNC could ever dump on a local market. The Rub3 Al Khali hung heavy with fruits and vegetables, and Saudi became one of the world’s major exporters of wheat and nightshades. Animals were relocated to the At-Taysiyah natural reserve, but the Arabian Oryx still came perilously close to extinction. Plantlife went to the King Abdullah International gardens, with genefiles and seeds sent to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, ECHO Asia, and the Millennium Gardens at Kew. And the mahgul fields grew, and grew, becoming more energy and resource intensive, just as Ruda shone a little brighter with each passing year. The fields were protected by Academi-Aegis, whose ‘Bamas (as the locals nicknamed the drones) occasionally mistook a villager for a threat, exterminating them.

There were few protests over these extrajudicial killings, not for fear so much as futility. It used to be that you could take your complaints to the offices of the subregional bureaucrats and be welcomed and heard in the old majlis style, and usually the families would receive blood money too, but private military companies changed all that. Nobody cared about these locals’ lives, but the plight of animals and the environment was another matter. International groups signed petitions and politicians made blustery, harrumphing remarks to their own constituencies, but nobody risked losing access to us, to our mahgul and our technology. A radical group named Jabhat Tahrir Al Ard, styled after the Earth Liberation Front, claimed responsibility for a small series of industrial attacks, but nobody took them very seriously.

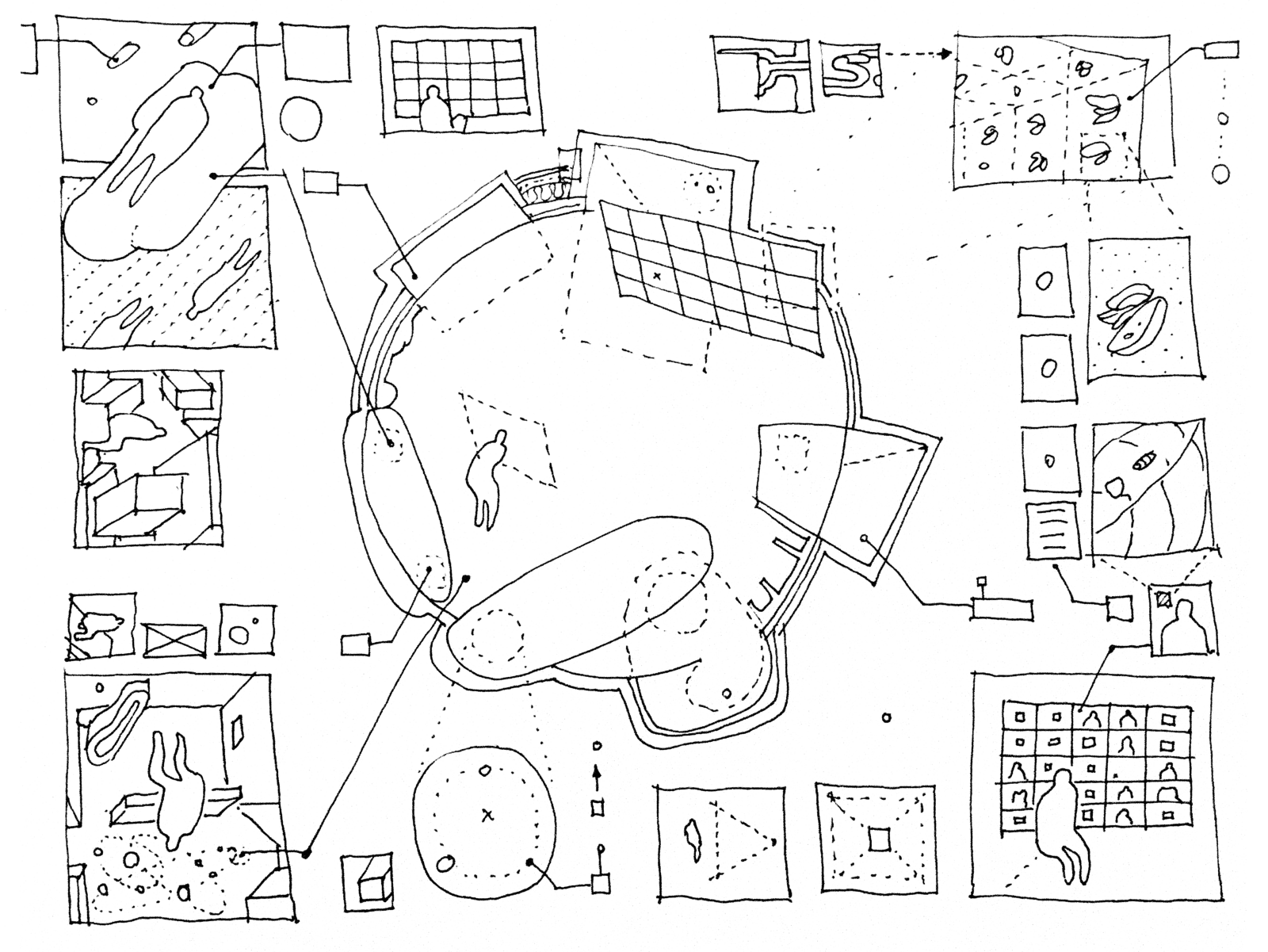

Then yields dried up, food was rationed, and maps and diagrams began to arrive. Detailed ones of the Tabuk region over the ages, of the Sinai Peninsula and of the coast of the red sea. Some seemed to show geological features and a kind of dendritic network that didn’t match any roads or waterways that I knew of. In places, they crossed the waters too, from Za3farana to Abu Zenima, from Ras Shukheir to El Tor, from Dahab to Magna. Others I could recognize: the long defunct Hejazi railway that once ran from Damascus to Medina, cutting directly through the megacity’s mahgul fields, and the Haifa-Riyadh-Abu Dhabi line that came into operation in the 2030s.

Shortly after famine set in, cryptic instructions arrived. What they seemed to want of me was simple: to help divert a single shipment of mahgul attar. One third would go to the Ateniyun, a third to the Jabhat Tahrir Al Ard—those crunchy bewaqoofs—and a third to the Taifi-Kazanlik Consortium—who had never quite recovered from the extended insult of that one night back in 2029. I was pretty sure the Consortium must have been bankrolling the operation: their once-resplendent roses were tinkered to be triple-yield, dried, and tinted to be exported for potpourri. Last I heard, it was pretty profitable. As for me, all I had to do was let their people in. I was the only one of their contacts with enough high-level access to make it possible. They assured me they would give me new papers and enough credits to start over, help me flee on the secretly restored Hejazi railway line, and get me to a place to remove my implanted ID chip. I could finally visit Sabzi and meet his wife and my godchild Mahbano; I could maybe even visit Jim Morrrison’s grave.

What could go wrong? Everything. I didn’t trust any of these sunbaked fools to have either the organization or yaichki to pull this off properly. The Ateniyun seemed well meaning and I had grown fond of them over the course of our long, one-sided epistolary relationship, but how much could you really trust a neo-Pharaonic solar cult? The Taifis and the Bulgarians were little more than preening Rose Uncles, trying to relive their glory days. As for the Jabhat, the less said about those corny treehuggers the better. It was almost certain extermination, and for what? With or without me, they were going to try something, and I knew the sun letters would be traced back to me. Besides, this was not my fight. The megacity had been good to me and I had no desire to see whatever these groups had planned play out.

I got out of that place. I checked myself out for emergency family leave, bought the requisite Ferrero Rocher and fuzzy blankets with scenes of Al 3ula and the mahgul fields, and I never went home. There was nothing left to go back to, after the typhoons had destroyed everything as far as the foothills of the Nilgiris. I knew a Palestinian smuggler who moonlighted as a grinder; she’d take care of my chip for me. I took a single vial with me, stuffed in a red-and-yellow tin of Classic Nido. You didn’t think I was going to leave with nothing, did you? I made that hand sign that I practiced all those years ago to the waiting men, who took me to the train. I never looked back. Who would triumph—the Ateniyun or the Residents, Aten or Ruda, the sun or the moon? I didn’t know and I didn’t care. I knew only one thing: the House always wins.

Sarah Cascone, “Archaeologists Say a Mystifying Group of Ancient Monuments in Saudi Arabia Suggests the Existence of a Prehistoric Cattle Cult,” Artnet, May 4, 2021, ➝.

Cascades is a collaboration between MAAT - Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology and e-flux Architecture.