France’s colonization of Algeria began in 1830 with war and dispossession.

Jacques Frémeaux, La France et le Sahara, 1830–1962 (Saint-Cloud: SOTECA, 2010), 233.

The Greenstream Pipeline departs from Libya and arrives in Italy. It is part of the Western Libyan Gas Project. In addition, there is a planned natural plan pipeline from Algeria to Sardinia and then further to northern Italy, named GALSI (Gasdotto Algeria Sardegna Italia). On the impact of North Africa on Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War, see, for example, North Africa and the Making of Europe: Governance, Institutions and Culture, eds. Muriam Haleh Davis and Thomas Serres (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

The three northern departments of Algiers, Constantine, and Oran were proclaimed as an integral part of France in 1848. France’s expansion into the Sahara Desert started in 1844 with the arrival of French soldiers in Biskra, a town located in the Ziban region at the edge of the desert.

On France’s colonization of the Sahara, see, for example, André Bourgeot, “La conquête coloniale au Sahara central ou L’utopie transsaharien,” L’histoire du Sahara et des relations transsahariennes entre le Maghreb et l’Ouest africain du Moyen Age à la fin de l’époque coloniale: actes du IVème colloque euro-africain (tenu) à Erfoud 20–25 octobre 1985, 1986; Benjamin Claude Brower, A Desert Named Peace: The Violence of France’s Empire in the Algerian Sahara, 1844–1902 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009); Frémeaux, La France et le Sahara; Daniel Grévoz, Sahara 1830–1881: Les mirages français et la tragédie des Flatters (Paris: Editions L’Harmattan, 1989); Paul Pandolfi, La conquête du Sahara, 1885–1905 (Paris: Karthala, 2018); Douglas Porch, The Conquest of the Sahara (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984).

On Algeria, France, Europe, and the Treaty of Rome, see, for example, Megan Brown, “Drawing Algeria into Europe: Shifting French Policy and the Treaty of Rome (1951–1964),” Modern & Contemporary France 25, no. 2 (2017): 191–208; Megan Brown, “A Eurafrican Future: France, Algeria, and the Treaty of Rome (1951–1975)” (PhD diss., City University of New York, 2017).

Marie-Monique Robin, Escadrons de la mort: l’école française (Paris: La Découverte, 2004).

Samia Henni, Architecture of Counterrevolution: The French Army in Northern Algeria (Zurich: gta Verlag, 2017), 51–78.

The premises behind this French colonial institutional project had existed since 1952. Frémeaux, La France et le Sahara, 236.

Law 57-27, Journal officiel de la République française: Lois et décrets, January 11, 1957. Translation by author.

Yvan du Jonchay, “L’infrastructure de départ du Sahara et de l’Organisation Commune des Régions Sahariennes (O.C.R.S.),” Géocarrefour 32, no. 4 (1957): 278. Translation by author.

Jean-Michel de Lattre, “Sahara, clé de voûte de l’ensemble eurafricain français,” Politique étrangère 22, no. 4 (1957): 351. Translation by author.

Ibid. Translation by author.

Samia Henni, “Toxic Imprints of Bleu, Blanc, Rouge: France’s Nuclear Bombs in the Algerian Sahara,” The Funambulist 14 (2017): 28–33.

“Rapport sur les essais nucléaires français 1960–1996, tome 1: La genèse de l’organisation et les expérimentations au Sahara CSEM et CEMO,” n.d., 65–68.

Bruno Barrillot, Les irradiés de la république: les victimes des essais nucléaires français prennent la parole (Brussels: Editions GRIP, 2003), 43–44.

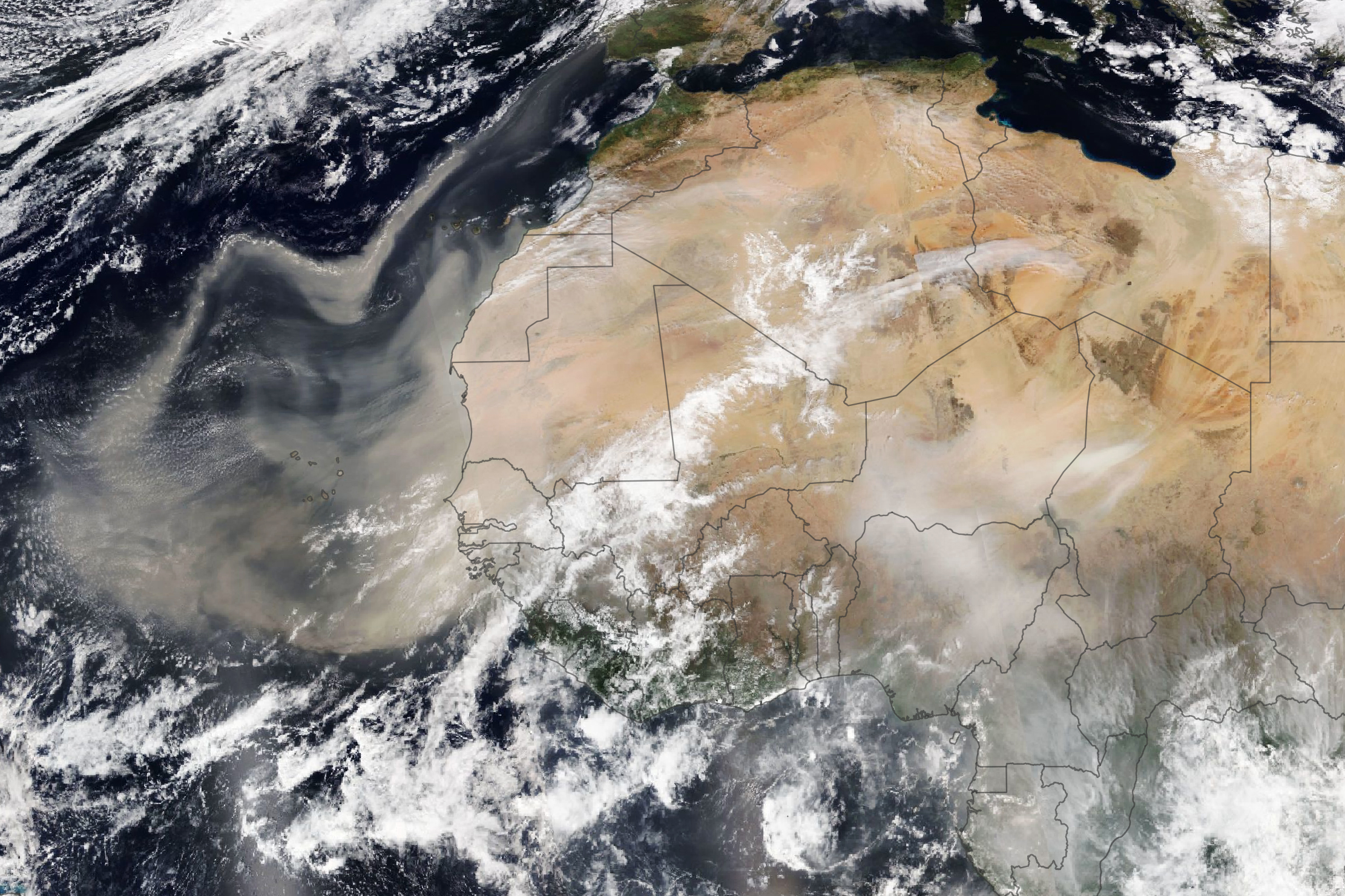

Rafael Cereceda, “Irony as Saharan Dust Returns Radiation from French Nuclear Tests in 1960s,” Euronews, March 1, 2021, ➝.