Frank Lloyd Wright, Modern Architecture, Being the Kahn Lectures for 1930 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1931), 65.

Jelly H.M. Soffers, Jill P.J.M. Hikspoors, et al. “The Growth Pattern of the Human Intestine and its Mesentery,” BMC Developmental Biology, August 22, 2015, 1–16.

Strictly speaking, the human animal excretes its shelter. Architecture is not only the hosting of excrement but is itself excremental. The excremental interior is composed of sedimented deposits. More strictly still, the interior is excreted by countless different species and is never simply outside the species that deposit it. Or, to say it the other way around, species are never simply inside. The human, for example, is never inside a building inasmuch as the building is part of it and so many others. Interiority has to be rethought as bacterial exchange, survival through mutually dependent co-existence with communities of others, just as the human is rethought as a metaorganism produced and sustained by mutually beneficial exchanges between countless microorganisms.

Florence Nightingale, “Sites and Constructions of Hospitals,” The Builder, August 28, 1858, 577.

“As it is a vital law that all excretions are injurious to health if reintroduced into the system, it is easy to understand how the breathing of foul air of this kind, the consequent re-introduction of excrementatious matter into the blood through the function of respirations will tend to produce disease.” Florence Nightingale, Notes on Hospitals (London: John W. Parker and Son, 1859), 11.

Florence Nightingale, Notes on matters affecting the health, efficiency, and hospital administration of the British Army: founded chiefly on the experience of the late war (London: Harrison, 1858), IX.

Ibid., 87.

The Sanitary Commission was led by the civil engineer John Rawlinson and the physician John Sutherland, who would become one of Nightingale’s closest colleagues and fellow campaigner. Sutherland was an expert in epidemic diseases like cholera and a founding member and advocate for the “health of towns” movement that had been the main lobby group for sanitary reform to channel all excrement through private toilets connected to public sewers since 1844. Their team was drawn from the Liverpool Sanitary Department that Sutherland was close to and had been the very first to appoint an inspector to target domestic and urban excrement that same year.

“We directed the frequent use of quicklime-wash for the purpose of cleansing the walls and improving the atmosphere of the Wards and Corridors. This we considered one of the most important sanitary precautions which could be adopted. Experience has shown that all porous substances, such as the plaster of walls and ceilings, and even woodwork, absorb the emanations proceeding from the bodies and breath of the sick. After a time, the plaster becomes saturated with the organic matter, and is a fresh source of impurity to the air of the Ward. It hence follows that unless the walls and ceilings of Hospitals be constructed of absolutely non-absorbent materials, it is necessary, at short intervals, to us some application capable of neutralizing or destroying the absorbed organic matter. Of all known materials, quicklime wash is one of the most efficacious agents for mitigating the virulence of epidemic disease.” “The Proceedings of the Sanitary Commission Dispatched the Seat of War in the East 1855-86,” cited in ibid, 95.

The Illustrated London News, December 16, 1854, 625.

Florence Nightingale, written response to questions, Report of the Commissioners appointed to inquire into the regulations affecting the sanitary condition of the army, the organization of military hospitals, and the treatment of the sick and wounded: with evidence and appendix, (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1858). 370.

Triggering a struggle over the limits of public authority, the 1844 Metropolitan Building Act already required all new buildings to be connected to sewers and the 1846 The Nuisances Removal and Disease Prevention Act encouraged property owners to clean existing buildings and connect them to sewers for “speedy removal” of excrement, giving local parishes the right to appoint inspectors that could enter private property to determine the degree of offensive matter. The 1848 Public Health Act effectively completed the tubular insertion of public into private by making such inspections and drainage systems mandatory.

Minutes of Information Collected with Reference to Works for the Removal of Soil Water or Drainage of Dwellings Houses and Public Edifices and for the Sewerage and Cleansing of the Sites of Towns, July 1852 (London: General Board of Health, 1852).

Paul Dobraszczyk, “Mapping Sewer Spaces in Mid-Victorian London.” In: Ben Campkin and Rosie Cox eds., New Geographies of Cleanliness and Contamination, (London: I.B. Tauris, 2007), 123–137.

Sewage of Towns: Preliminary Report of the Commission appointed to Inquire into the Best Mode of Distributing the Sewage of Towns, and Applying it to Beneficial and Profitable uses / Presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty (H. M. Stationary Office, 1858).

The survey presented endless examples of excremental accumulation up to three feet deep in the unventilated basements of crowded lodging houses, as “immense dunghills” in courtyards, or accumulating and decomposing alongside buildings in alleyways and streets. It relentlessly details overflowing cesspools, seepage down or through walls, between rooms, and the soiled condition of bodies, clothing, bedding, furniture, floors, and wall surfaces. The text effectively blamed the laboring poor and their landlords rather than the extractive nature of the industrial economy, even contrasting them with “wild animals” that conceal their own waste and keep their distance from it. Edwin Chadwick, Report from the Poor Law Commissioners on an Inquiry into the Sanitary Conditions of the Laboring Population of Great Britain. (London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1842), 24.

Ibid., 48–52.

Edwin Chadwick, letter to Lord Francis Egerton, October 1, 1845. Cited in Samuel Finer, The Life and Times of Sir Edwin Chadwick, (London: Methuen, 1952), 222.

From 1842 onwards, Chadwick would keep pushing for such a system, carrying out experiments with different types and sizes of sewer pipe feeding hoses and spray jets. Edwin Chadwick, Sewer Manure. Statement of the Course of Investigation and Results of Experiments as to the Means of Removing Refuse from Towns in Water and Applying it as Manure: With Suggestions of Further Trial Works (For Voluntary Adoption) of the Practicability of Applying Sewer Water as Manures by Subterranean Channels, (London: Reynell and Weight, 1849). Chadwick instigated the 1848 scheme of the engineer Henry Austin to gather all London sewage down into four central points and use steam pumps to pipe it radially outward and upwards to surrounding agricultural fields. Austin developed an entire architecture for receiving, “deodorizing,” and distributing sewage with specialized plumbing, buildings, and pumps connected via buried nets of pipes to hydrants emerging in the center of agricultural fields that feed iron or canvas hoses and spray jets.

Having successfully insisted that excrement could no longer be considered private property since it so endangered public health, the General Board of Health controlled by Chadwick imagined a plumbing circuit in which excrement continuously passed from private to public to private, and so on. Henry Austin’s December 1851 minutes of the Board presented to parliament analyzed the success of farms using steam engines to spray liquid manure and proposed layouts of such countryside plumbing to show how public steam pumps under public roads could feed multiple private farms to, as it were, fully integrate excrement into the capitalist economy. Henry Austin, Minutes of Information Collected with Reference to Works for the Removal of Soil Water or Drainage of Dwelling Houses and Public Edifices and for the Sewerage and Cleansing of the Sites of Towns, December 1851 (London: General Board of Health, 1852).

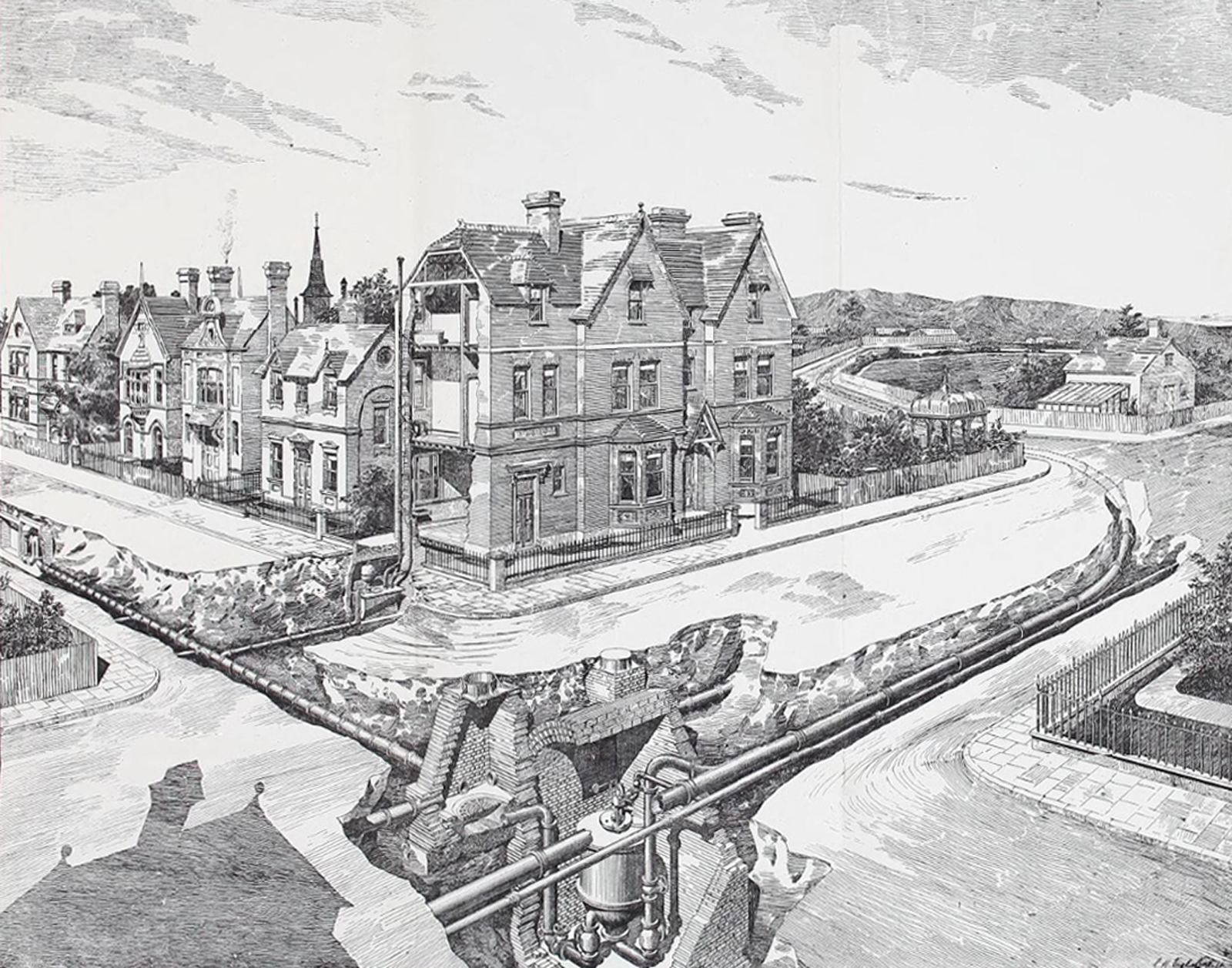

Chadwick was sidelined out of the government process in 1854 and his goal of a self-sustaining infrastructure was removed from consideration during the final evaluation of Bazalgette’s scheme in 1857. It was revived by new government committees and discussed weekly throughout the 1860s and early 1870s in newspapers and professional magazines obsessed with the huge untapped value of urban excrement, with Chadwick returning to the center of the debate with a number of new experiments and projects. Even Issac Shone’s Hydro-Pneumatic sewage flushing ejectors using air compression, patented in 1878 and installed in the main sewers of the houses of parliament in 1887, had been promoted as a network system to be installed in all houses, alleyways between houses, streets, and major intersections, leading to matching ejectors in individual farms to spray the excrement. Hughes and Lancaster, The Shone Hydro-Pneumatic System (Liverpool: Rockliff Brothers, 1885). Shone’s publication of the new sewage system for parliament began with a declaration of his longstanding dedication to Chadwick’s philosophy of separating sewage from drain water and guiding it to the countryside—illustrating a domestic house suspended in such an expanded system. Issac Shone, Westminster, on the Shone Hydro-Pneumatic System: with drawings and hydraulic sewage table (for office reference for architects and engineers) explanatory of scientific and sanitary drainage, (London: E. and F. N. Spon, 1887). While none of the many such schemes for a complete technological-biological circuit were successful, the concept would ultimately be realized when the outflows guided into the Thames at a distance downstream from the metropolis were belatedly re-diverted into sets of vast technologically complex treatment plants and from there to agricultural fields and back to the city.

The folded pipes of the sanitary appliance maintain a stable line between inside and outside while allowing excrement to pass in one direction through that line, moving from the visible “clean” white porcelain extension of the pipe into the room into the invisible “dirty” blackness within the building’s structure. The visible orthogonal geometry of the building with its seemingly straight sealed lines is sustained by elaborate hidden folds.

Nightingale took over the leadership role of the movement by reviving Chadwick’s still controversial central argument for channeling excrement away from daily life and coining the concept of the “health of houses” as “pure air, pure water, efficient drainage, cleanliness, and light” that would ultimately shape modern architecture in her most famous book that Chadwick had encouraged her in 1858 to write. Florence Nightingale, Notes on Nursing, (London: Harrison, 1859), 14–17.

Leon Battista Alberti, On the Art of Building in Ten Books, trans. Joseph Rykwert, Neil Leach, and Robert Tavernor (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1988), 295.

Ibid., 151.

Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ piu eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostril (Florence: 1550), 50.