Merriam Webster, s.v. “Animate (transitive verb), 2a,” ➝.

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), viii. See also: Diana Coole and Samatha Frost, “Introducing the New Materialism,” New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics, ed. Coole and Frost (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010).

For more on electricity, food, and metals, see Bennett, Vibrant Matter, 25, 39, 59.

Bennett, Vibrant Matter, 121. Mel Y. Chen also considers “how matter that is considered insensate, immobile, deathly, or otherwise ‘wrong’ animates cultural life in important ways” in Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 2.

Karen Barad, “Matter feels, converses, suffers, desires, yearns, and remembers: Interview with Karen Barad,” New Materialisms: Interviews and Cartographies, ed. Rich Dolphijn and Iris van der Tuin (Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press, 2012) 61. See also: Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007).

J. L. Austin, How To Do Things With Words (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962), 5-6.

For more about performative slippages, see: Jacques Derrida, “Signature Event Context,” Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 307-330.

Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London: Routledge, 1993), 150.

AI can and does “hallucinate” and misfire in a way parallel to Austin’s performatives. See: Katherine Lee, Orhan Firat, Ashish Agarwal, Clara Fannjiang, and David Sussillo, “Hallucations in Neural Machine Translation,” Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2018, Montreal, Canada, ➝.

Lauren M. E. Goodland, “Editor’s Introduction: Humanities in the Loop,” Critical AI 1, no. 1-2 (October 2003).

Goodland, “Editor’s Introduction,” 2. See also: Terrance J Sejnowski, The Deep Learning Revolution (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018), xi.

Lena Smirnova et al., “Organoid intelligence (OI): the new frontier in biocomputing and intelligence-in-a-dish,” Frontiers in Science 1 (February 28, 2023); also, Cortical Labs in Melbourne is working on a neurobiological platform, “DishBrain,” that can run very basic programs. They’ve already had a 2D layer of 800,000 neurons learn to play the video game Pong. See: Dan Robitzski, “How Neurons in a Dish Learned to Play Pong,” The Scientist, October 12, 2022, ➝.

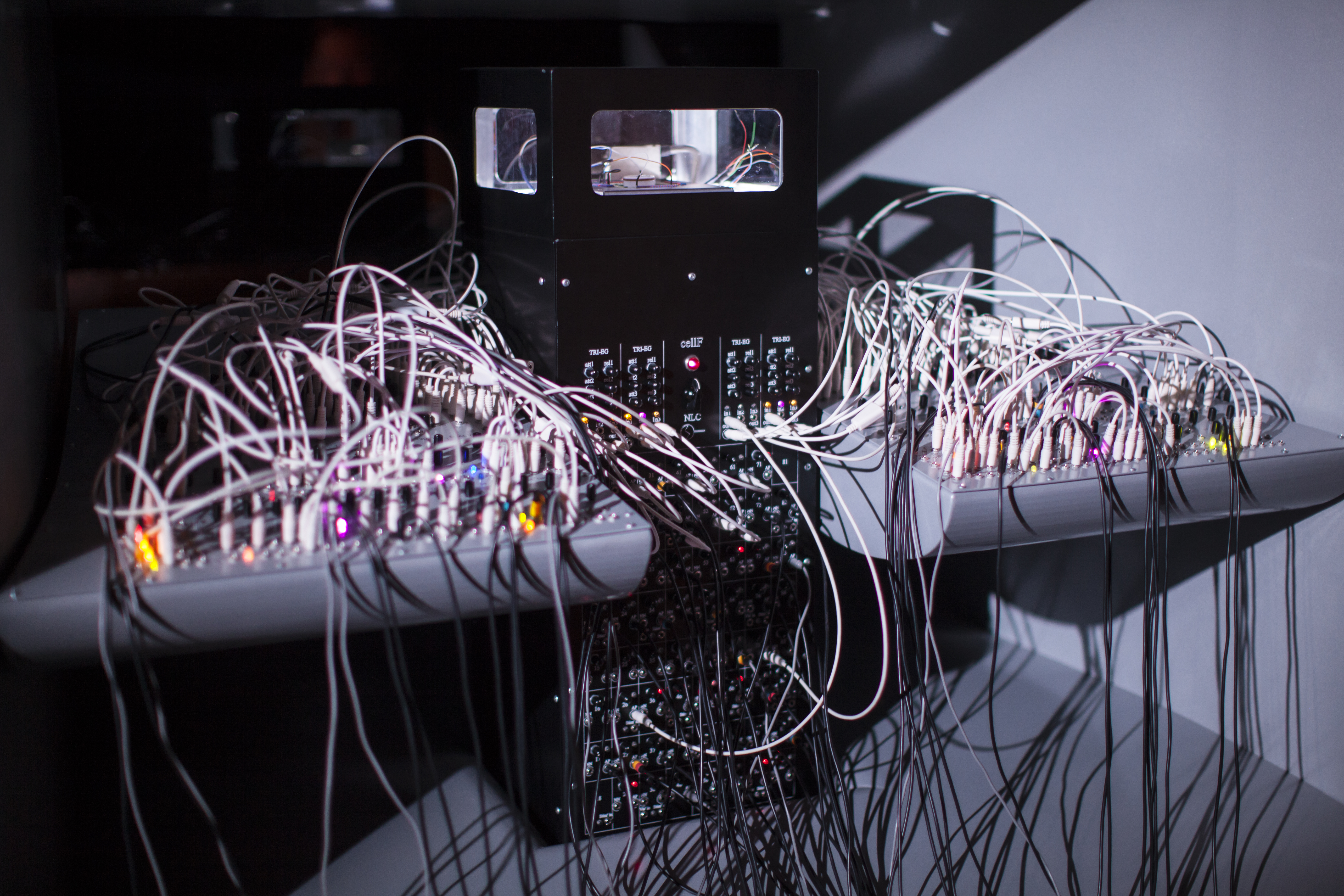

cellF was developed by Ben-Ary in collaboration with artist Nathan Thompson, electrical engineer Andrew Fitch, scientists Stuart Hodgetts, Mike Edel and Douglas Bakkum, and musician Darren Moore. Vahri Mckenzie, Nathan John Thompson, Darren Moore, Guy Ben-Ary, “cellF: Surrogate Musicianship as a manifestation of in-vitro intelligence,” Handbook of Artificial Intelligence for Music, ed. Eduardo Reck Miranda (Switzerland: Springer, 2021), 915-932.

The majority of embryonic stem cell lines have historically been cultured from surplus in-vitro fertilized embryos that will no longer be implanted. Now we can generate pluripotency, or the capacity of stem cells to develop into any adult cell. In 2006, Shinya Yamanaka discovered that he could reprogram mouse skin cells to act like embryonic stem cells, causing those cells to revert to a prior, nascent state. Like embryonic stem cells, these “induced pluripotent stem cells,” or iPS cells, can self-renew and differentiate into all adult cell types. See: Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka, “Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors,” Cell 126 (August 2006): 663–676.

Similarly developed from reverse-engineered stem cells, organoids are very small, 3D cell cultures that structurally self-organize and differentiate into specific organ tissues. Within a rotating bioreactor that simulates gravity, these mini-organs can self-assemble up to 5-millimeters in width and, to date, scientists have grown mini-brains, kidneys, lungs, intestines, stomachs, and livers. J. Kim, B.K. Koo and J.A. Knoblich, “Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine,” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 21 (2020): 571–584. To achieve three-dimensionality as well as complex cellular development and function, scientists embed pluripotent cells in an extracellular matrix, which is the structural support that all cells have. This matrix serves as the microenvironment that supports 3D tissue growth.

When Lucier died, in December 2021, his “mini-brains” (cerebral organoids) were alive and his family agreed that the project should continue.

In similar manner to his foundational 1965 performance Music for Solo Performer. Alvin Lucier, "Musik for soloist/Music for Solo Performer," Fylkingen Bulletin: International Edition, Art and Technology II2 (1967): 16-17. See also: Guy Ben-Ary, Nathan Thompson, Stuart Hodgetts, and Andrew Fitch, Music for Surrogate Performer (2023), Venice Biennale, ➝.

Personal conversation with Ben-Ary, Thompson, and Hodgetts (January 18, 2022).

As medical anthropologist Linda Hogle makes clear: “Human embryonic stem cells are elusive, recalcitrant entities that resist characterization and standardization” with their “distinct, cumulative identities” that change according to the specific lab environments in which they are grown. See: Linda F. Hogle, “Characterizing Human Embryonic Stem Cells: Biological and Social Markers of Identity,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 24, no. 4 (December 2010): 433.